1950s_Rock_and_Roll_.. - Have you ever had a teacher who

advertisement

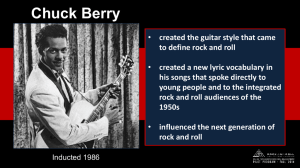

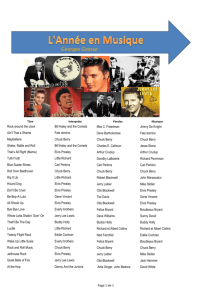

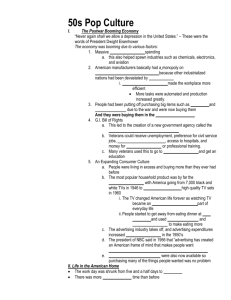

The 50’s When the party started, and Elvis was King. “UGGHH, HE’S SO VULGAR! Turn it off!” My mom and I were riding in our frankfurterlike Nash Rambler, listening to the woofing, staticky radio with the fat white dials big as saucers. With the windows rolled down, we were cruising in the wind of 1956, the year of Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog.” Again, Mom yelled: “Off! Turn him off!” “But what’s so horrible about him?” I asked. She snapped the dial. “Because he’s sleazy, is why! Calling a lady a hound dog! And using ain’t. It’s disgusting.” Like millions of other Americans, my mother was shocked by Elvis’s performance on the Milton Berle Show (Three Months before Ed Sullivan). This was the show where he’s done the grunting, spraddle-legged reprise, slow as a burlesque grind, that has caused such a furor. Frank Sinatra, the idol of her generation, loathed this new sensation, reportedly calling him a rancid-smelling aphrodisiac. Of course Elvis threatened them. This wasn’t the sad, bloated effigy of the 1970’s, with the sequined bell-bottoms and dyed hair. This was the handsome, snarling, 20-year-old immortal, humping his guitar with hi slegs goinig every which way and that look of rude ecstasy, singing: You-ain’-tah-nuth-thin-but-a-houn’-dog… My mother wasn’t some PTA biddy. She was young then, just 31. But with “Hound Dog” she forever relegated herself to another time and sensibility, unable to grasp the new in a guise so raw and raucous-to her, unpretty. And so as a kid in 1956, you hit a wall: You hit that wall of THEM. And let’s face it, after Elvis, it was THEM, all the post-Depression, postwar, GIbill, up-by-your-bootstraps, white-bread generation, mowing their lawns, drinking their hard-earned martoonies and struggling, most of them, to clasp that next rung up in the suburban middle class. That’s the staid party “the Pelvis” was crashing. In an America so square and easily shockable, it was virtually inevitable-essential, one might say-that others would also feel obliged to rock the boat…Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Ala., bus (1955)…or beat poet Allen Ginsberg coming out with his wakeup call Howl (1956), rhapsodizing about sex and drugs and “angel headed hipsters.” Reds, tight pants, juvenile delinquency, necking, girls or boys with “reputations”-all this and more rattled our parents. Sternly, my father warmed me, “If you let loose with an off-color story in polite mixed company, people will cut you off forever, do you hear me?” Sam Phillips wasn’t worried. “If I cound find a white man who has the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a million,” said the founder of Sun Records in Memphis. He started out recording black rhythm and blues artists like Ike Turner, Rufus Thomas and Chester “Howlin’ Wolf” Burnett, and by the early 1950’s, it was clear to Phillips and other white producers that black music, the music that would spawn rock and roll, was electrifying white kids, kids who were starved for something hot and liberating. Elvis, then was the messenger. He was the voice that carried the news of a multitude of great messengers, black and white, but mostly black. And that was the greatness of Elvis, it seems to me, that he could have carried so many threads and experiences in a single voice. It was all there. Blues, gospel and country, Honky-tonks, fast cars, youth and freedom, and, above all, the incendiary notion that you could actually be white and cool. Like most miracles, it was short-lived once Elvis became a national commodity and got mixed up with Colonel Parker and Hollywood and Las Vegas. While there were some scorching singles from his RCA-record period-records like “Heartbreak Hotel” and the kick-ass ”Jailhouse Rock”-for me nothing else achieves quite the same free-flowing purity of those first sessions he did for Sam Phillips in ’54 and’55. “That’s all Right”…”Mystery Train”…”Good Rockin’ Tonight.” What’s wonderful about these recordings, as with so much music of the era, is their almost casual simplicity: Scotty Moore’s great guitar work, Bill Black’s thunking string bass, hand claps, drums. “you couldn’t just mash buttons and sound like a band.” In his Sun period, Elvis was part of Phillip’s “Million Dollar Quartet,” which included Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee, Lewis and Carl Perkins. Now Elvis barely wrote a note of music-few performers did in those days-but Carl Perkins sure did. Almost out of nowhere, Perkins hit perfection with such early classics as “Blue Suede Shoes,” “Boppin’ the Blues,” and “Honey Don’t.” Along with Chuck Berry, Perkins also deserves a lot of credit for inventing the classic rock and roll riffs still heard today. The Beatles idolized him, especially George Harrison, who taught himself to play guitar by slowing down Perkins’s records. In fact, you can hear George copy Perkins lick for lick in such high energy Beatles covers as “Matchbox,” and “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby.” Remember Robert Mitchum in The Night of the Hunter, the derangd southern preacher with GOOD and EVIL tattooed on his knuckles? For me, that’s Jerry Lee Lewis, Jimmy Swaggart’s wild-eyed, star-crossed cousin. Nor for nothing he was named the Killer. What a rock schooling! Whorehouse piano player at 14. Bible school washout. Break in artist and door-to-door salesman with his Sunday airs and chickenthieving grin. Lock up your daughters, Pop, ‘cause this boy’s scary when he starts banging on his piano-when his golden curls come unhinged and he bolts up from his stool like a man in the grip of an angelic seizure. Jerry Lee still sends the old tequila-shooter shivers down my spine when I hear “Whole Lotta Shakin’” (Mummmmmmmmmmm…………feeeeeellzzzzz geeeeeee-ooooooddddddd) and that shuddering climax of a morality play, “Great Balls of Fire” (You broke my will, but what a thrill). Bad? The man’s ancestors must have danced with snakes. Then, of course, there was Buddy Holly, a singer who makes me wonder if there isn’t reincarnation. In 1953, at the age of 29, Hank Williams died of drugs and exhaustion in the backseat of his Cadillac, but to hear Buddy Holly rock in “Rave On,” “Maybe Baby” and “Oh, Boy!” is to wonder if Hank didn’t somehow book a return seat to the party. In Buddy’s Lubbock, Tex., voice you hear much of the same lyric purity, plus that absolute correctness of emotion, of which Williams was a master. Still, the similarity isn’t all that surprising: Holly was an unsuccessful country artist before Elvis inspired him to bridge the two worlds. He had little of Williams’s darkness, but in his hiccupping, often deliberately nerdy phrasings, he perfectly captured something else-youth: its delight and exuberance, its sadness, sweetness, awkwardness, fugitive longings and, yes, even its unabashed callowness. Artist that he was, he put it all in. What’s more, Holly was an innovator, one of the first to use double-tracking and the one who popularized the classic two-guitar, bass and drum line-up uses by, say, the Beatles. In fact, it’s no big stretch from “That’ll Be the Day” to “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” The Beatles borrowed more than their name from Buddy Holly and the Crickets. Kids don’t, as a rule, write novels or concertos, but with rock, they were able to grab America like a gooseneck mike and wail their lives into it. And what an array of styles and voices: the Everly Brothers (“Wake Up Little Susie”), Gene Vincent (“BeBop-A-Lula”), Frankie Ford (“Sea Cruise”), Eddie Cochran (“Summertime Blues”), Duane Eddy (“Rebel Rouser”), Bobby Darin (“Splish Splash”), Dion and the Belmonts (“I Wonder Why”). Now for the flip side, the black side-race music, as it was called until the early ’50 when the NAACP finally put a stop to the segregationist label. By they, whites were buying black music, but even so, black artists still found themselves on the outside looking in. Imagine their frustration when, often within weeks, their hot new records were “covered”-copied-by white performers. By then, whites were buying black music, but even so, black artists still found themselves on the outside looking in. Imagine their frustration when, often within weeks, their hot new records were “covered”-copied- by white performers. And sanitized. One famous example is Joe Turner’s lascivious “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” a tune almost instantly covered in 1954 by Bill Haley and His Comets. The less fortunate got waxed by the dean of diluters, the squeaky-clean Pat Boone in his white bucks. Such a covering genius was Boone that he even turned Little Richard’s outrageous “Tutti Frutti” into slush. Today, Little Richard says Boone’s version “opened the highway for acceptance.” On the other hard, Richard claims it was his version that “really started the races being together,” the whites jumping down from the segregated balconies to rock with the blacks by the stage. With his gospel frenzy and mascara’d eyes, he bridged the races and sexes both, the papa and big mama of such provocateurs as David Bowie, Prince, Michael Jackson and Madonna. In the ‘50s we likewise see the black genius for making art out of making do. In much the way rap music was the brainchild of kids who couldn’t afford musical instruments, doo-wop came from urban kids catting it up in alleys, tenement hallways and subway stations. Dom-dom-de-dom. Ramma-lamma-ding-ding-ding. A bass so low the guy sounded like he’d had a lobotomy- and on the upper end, a guy dizzily trilling, singin’ and poppin’ alo about this li’l girl, an’ I was walkin’ down the street, an’ she was lookin’ so fine. Among the groups that started as street corner amateurs were Little Anthony and the Imperials (“ Tears on My Pillow”), Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers (“Why Do Fools Fall in Love?”), the Dells (“Oh What a Night”), the Crows (“Gee”) and the Flamingos (“I only Have Eyes for You”). These last two are what rock ornithologists call the Bird Groups, which also include the Penguins (“Earth Angel”) and the Oriels (“Crying in the Chapel”). The list of classic black vocal groups goes on and on: the Platters (“The Great Pretender”), the Drifters (“There Goes My Baby”), the Five Satins (“In the Still of the Night”) and those wonderful clowns, the Coasters (“Poison Ivy”). For last, I save the greatest of any of them, black or white. For me, that’s Chuck Berry, the man who comes even closer than Elvis to bridging the races. Berry credits blues masters Muddy Waters and Elmore James as two important early influences. Still, it’s a stunning leap from the brooding, slowhumping power of blues, or the high-energy twang of country, to the walloping, locomotive force of: You know my temperature’s rising, the jukebox blowin’ the blues Roll over, Beethoven, Tell Tchaikovsky the news… The freshness of these songs, their wit and rapid-fire narrative compression- the sheer volume of information they pack- never fail to astonish me. Duck-walking and firing off bursts of that itchy, machine-gun guitar, Chuck Berry was as instrumental to the Beatles as to the Rolling stones, who must hold the record for covering Berry classics, like “Around and Around,” “Little Queenie” and “Carol.” Everything has its time to be, and by the late 50’s the early miracle of rock was foundering. In 1957, claiming he feared damnation, Little Richard stopped performing and took refuge in religion. Then Chuck Berry ran afoul of the Mann Act, transporting Sweet Little Sixteen (she was actually 14) across the Missouri line in a red Ford, a charge that eventually landed him in prison for two years. And at the height of his fame, Jerry Lee’s career crashed and burned when he married his 13 year old second cousin, Myra. Like Judas goat, he was driven for yeas into the American wilderness of third-rate clubs, booze, drugs, mayhem with loaded guns and tragedy. Elvis, meanwhile, got drafted into the Army, and Buddy Holly’s plane plowed into an Iowa cornfield, taking with him Ritchie Valens (“La Bamba”) and the Big Bopper (“Chantilly Lace”). Nature, as they say, abhors a vacuum, and so in Liverpool, England, four young men learning their lessons from giants like Carl Perkins, Little Richard, and Chuck Berry. A tornado was brewing, and we now know precisely when and where it set down: February 7th, 1964, in New York’s Kennedy Airport, with cordons of cops and mobs of screaming fans. Gentleman that he was, Elvis even sent his heirs apparent a congratulatory telegram.