AP Art History 20

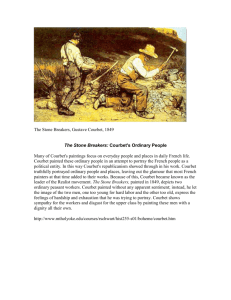

advertisement

Richard Ceballos March 18, 2009 Unit 20-Romanticism/Realism Romantic Landscape Painting The sublime, come from philosophy, we have all had experiences with the sublime Has nothing to do with beauty, beauty connected with form Found in the formless, element of fear, limitless, infinity, the object itself is not sublime Caspar David Friedrich Considered Germany’s greatest Romantic landscape artist Figure 30-21, CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH, Abbey in the Oak Forest, 1810. Dead trees, infinite space, tombstones, real subject is nature John Constable The most famous English landscape artist Figure 30-22, JOHN CONSTABLE, The Haywain, 1821. Expresses emotion in a different way, nostalgic view Little dog contemplative, looking back before Industrial Revolution Scene is what he saw was disappearing JMW Turner Figure 30-23, JOSEPH MALLORD WILLIAM TURNER, The Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), 1840. Different Romantic agenda, exploring themes of the sublime Turbulent nature, humanity’s insignificance Does not focus on narrative, all about atmosphere No matter what humans do, nature is always indifferent The Hudson River School Group of artists that shared the same ideas America’s first movement Realistic attention to detail Figure 30-24, THOMAS COLE, The Oxbow (View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm), 1836. Leader of the school Dark, uncontrollable nature vs. lightened civilization Little man in the middle Figure 30-25, ALBERT BIERSTADT, Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains, California, 1868. Strong thirst for these Western paintings, back east Traveled with military, propaganda, successful Used as an argument, pro-Manifest Destiny Idealized depiction, divine light pouring over the mountains Figure 30-26, FREDERIC EDWIN CHURCH, Twilight In the Wilderness, 1860s. Peaceful element, during Civil War, beauty and power of nature Realism pages 798-818 Europe and America around 1850-1870 Era of Revolutions, scientific, industrial, social, and artistic Brief Background and Context Realism: the movement Art movement 1850 to 1870 Depict what is actually seen in the world Empiricism (observation and direct experience) Poor moving to the cities Philosophies based on working rights, Communist Manifesto, Capitalists 3 Revolutions in France Revolutions help explain the movement, what is seen in the real world Precursors to Realism Genre paintings from such artists as Peter Bruegel, Louis Le Nain, Chardin Realism’s Key Artists Realist Painters Gustave Courbet Jean-Francois Millet Honore Daumier Rosa Bonheur Edouard Manet Birth of Photography Nadar Eadweard Muybridge Courbet! The French Salon (government exhibit, judges only accept academic art) The Pavilion of Realism Courbet rented a space next to the French Salon, 20 pieces rejected Also wrote the Realist Manifesto, explains his works, portrayed common people and his time as he saw it Figure 30-27, GUSTAVE COURBET, The Stone Breakers, 1849. Toughest jobs around, critics hated it, thought there were social undertones, people hated the color too and called the conventions unsophisticated Figure 30-28, GUSTAVE COURBET, Burial at Ornans, 1849. Regular folks in a hometown at a funeral “The death of Romanticism”, Courbet referred to the painting as Monumental aspects is the scale Composition is democratic, row of humanity, no pyramid structure Draw attention to the issues of modern life