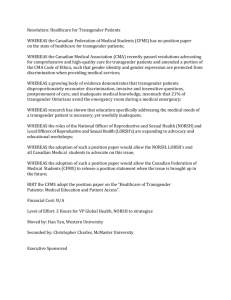

Background paper - Anti-Discrimination Board NSW

advertisement