Sample Paper

advertisement

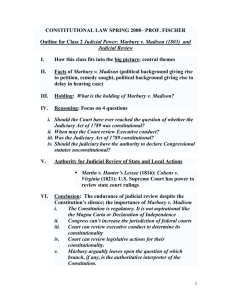

Introduction Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cr. 137 (1803), is perhaps the most controversial United States Supreme Court cases ever. Few experts would dispute that the impact of Marbury v. Madison has forever changed the United States government and the role of the courts in our government. According to Epstein and Walker, judicial review can be defined as “ the authority of a court to determine the constitutionality of acts committed by the legislative and executive branches and to strike down acts judged to be in violation of the Constitution” (Epstein and Walker 1995, p. 630). Judicial review is worthy of being studied for a number of reasons: (1) the Constitution does not clearly give the courts the authority of judicial review, (2) what standards should be used when nine un-elected officials in a democracy are judging the law, and (3) should the Court have this very powerful weapon. Most importantly, judicial review should be investigated because it has forever changed the United States’ political system. The purpose of this paper is to examine the United States Supreme Court’s decision of Marbury v. Madison, the background of the case, the case’s effect on the role of the Court, basic arguments for and against judicial review, and the case’s effect on federalism. Judicial Review and the Court’s Majoritarian Difficulty Judicial review by the Supreme Court has raised many controversial issues concerning the role of the Supreme Court. The federal judiciary is the least democratic branch of our government, yet it has the power to act as a final constitutional judge, and the fact that it can serve central values in our society seems to undermine the perception of democracy. According to Choper (1980), three very broad questions immediately come to mind when it comes to the idea of judicial review: (1) who determines when the Constitution has been violated, (2) by what standards should the matter be judged, and (3) what method should be used when determining whether or not constitutional lines of our democracy have crossed? According to Choper (1980), the first question of who shall determine when the Constitution has been violated seems to have been answered early on in our history. Marbury v. Madison established a precedent for judicial review of Congressional legislation, and later the Court extended its power to review state legislation. Thus, the Court established itself as the wielder of judicial review. It is important to note that Marshall’s opinion in Marbury set up an unveiled signal of judicial review. The signal for judicial review was later explicitly confirmed by Chief Justice Taney, and the Court has consistently acknowledged that the answer to some Constitutional questions rest in the other branches of the government (Choper 1980, p. 61-62). It is important to note that there are different theories about who should interpret the Constitution. Evidence in the Constitution suggests that the executive and legislative branches of government also should be responsible for interpreting the Constitution. According to Murphy (1986), Article I, Sec. 8 of the Constitution clearly implies that Congress shall have the authority (with the president’s approval) to make laws that are “proper” under the Constitution. He also suggests that similar terms in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-third, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-sixth Amendments indicate that Congress has the authority to interpret the Constitution. In the same article, Murphy suggests that Article II indicates that the president also has the authority to interpret the Constitution. He notes that Article II indicates that the president must “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution.” Murphy notes that it be impossible for the president to do his or her job without interpreting the Constitution (Murphy 1987, p. 39). According to Murphy (1987), there are three theories that claim to provide the answer to the question of who shall interpret the Constitution. The three theories are known as judicial supremacy, legislative supremacy, and departmentalism (Murphy 1987, p.39-41). Judicial supremacists argue that the judicial branch should interpret the Constitution. Judicial supremacists point to functional and textual support used in Marbury, Article IV, and the intrinsic nature of the court to justify their arguments. However, Murphy (1987), also maintains that the Constitution does not expressively give the Court judicial review, and judicial review does not indicate its obligations to the other branches. Murphy (1987) argues that legislative supremacists believe Constitutional interpretation should be performed by the legislative branch. Theorists under this doctrine often argue that impeachment could be used to make judges bow to the power of the legislature. However, Murphy (1987), indicates that constitutionalism is reluctant to give elected officials this final authority of review. Conclusion In summary, Marbury v. Madison and the power of judicial review have evolved into a very powerful and important function of the United States Supreme Court even though it is not explicit in our nation’s great Constitution. Marshall must have been aware of the Court’s limited power, and he set up an unveiled precedent of power. His keen insight enabled him to notice that the political situation was right, and he seized the opportunity to hand down one of the most controversial decisions ever. The fact that the development of judicial review was slow and that the Court did not abused its new power were both instrumental in the development judicial review. After researching Marbury v. Madison and judicial review, I believe that the Court should have this profound power. Structurally the Court is the weakest because it does not posses either the sword or the purse, so it makes sense that the Court would receive this power. I believe that the political isolation of the Court also justifies the Court development and use of the power. The Court’s isolation allows it to make less-passionate decisions without worrying about reelection unlike elected officials. The idea of departmentalism also promotes the idea of judicial review because the practical realities of real life indicate that all three branches of the government must interpret the Constitution. As for the existence of judicial review, I believe that it is necessary for the Court to possess this power because the Constitution is capable of being antimajoritarian when it is practically applied to real life. Based on these preceding arguments, I believe that very compelling and practical arguments for the use of judicial review by the Court has been justified. The role of the Court has clearly changed throughout the history of the United States. When the United States was founded and as it began to develop, the power of the Court was relatively minor. As the United States began to mature, the Court’s power also began to mature. Marbury v. Madison is definitely a powerful and successful precedent for the Court. Some people would argue that Marbury is a precedent of unconstitutional power, and others argue that it is essential for a democracy. Whatever the case, the Court has the power, and the Court has slowly developed the power into possibly the strongest weapon that our government has to offer to control itself. The federal government can use the power of judicial review to control legislation from the state governments, and to promote the idea of national supremacy. Therefore, it can be argued that judicial review has had an important effect on federalism. Marbury v. Madison has arguably tested the limits of the U.S. Constitution, and it has become a very powerful precedent for the Court. However one wants to put it, nine un-elected officials in a democracy have the power to make final decisions about the law. The Constitution could be amended to overturn the Court’s decision, but as history indicates, amending the Constitution is not an easy task. REFERENCES Choper, Jesse. 1980. Judicial Review and the National Political Process. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Clinton, Robert. 1989. Marbury v. Madison and Judicial Review. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. Cox, Archibald. 1987. “The Role of the Supreme Court: Judicial Activism or SelfRestraint.” Maryland Law Review 47 (Fall 1987): 118-129. (LEXIS/NEXIS) Domino, John. 1984. Civil Rights & Civil Liberties Toward the 21st Century. New York, New York: HarperCollins College Publishers. Eaton, William. 1988. Who Killed the Constitution? New York, NY: Kampmann & Company, Inc. Epstein, Lee, and Walker, Thomas. 1995. Constitutional Law for a Changing America: Institutional Power and Constraints. Washington D.C.: Congressional Quarterly, Inc. Fisher, Louis. 1995. Constitutional Structures: Separated Powers and Federalism. United States of America: McGraw-Hill, Inc. Hopkins, John. 1993. The Constitution of Judicial Power. Baltimore, MY: The Hopkins University Press. Lasser, William. 1988. The Limits of Judicial Review. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina. Luban, David. 1980. “Justice Holmes & the metaphysics of Judicial Restraint.” Duke Law Journal 44 (December 1994): 449-464 (LEXIS/NEXIS) Marbury v. Madison. (1803, February). U.S. Lexis [Online], 352 (77 Screens). Available: [1998, March 19]. Moschzisker, Robert. 1971. Judicial Review of Legislation. New York, NY: Da Capo Press. Murphy, Walter. 1987. “Who Shall Interpret? The Quest for the Ultimate Constitutional Interpreter.” In Fisher, Louis, Constitutional Structures: Separated Powers and Federalism. United States of America: McGraw-Hill, Inc. Newmyer, Kent. 1968. The Supreme Court Under Marshall and Taney. New York, NY: Thomas Y. Crowell Company.