Supreme Court - SISHurtTAPUSHistory

advertisement

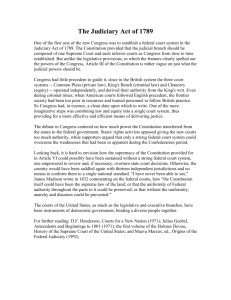

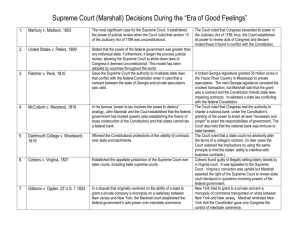

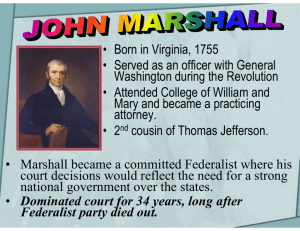

John Marshall and the Supreme Court Excellent Website on the Supreme Court: http://www.supremecourthistory.org Website on the history of the members of the Supreme Court: http://www.supremecourtus.gov/about/members.pdf Current Court: Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, Justice John Paul Stevens, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., Justice Antonin Scalia, Justice Sonia Sotomayo, Justice Stephen G. Breyer, Justice Clarence Thomas, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Justice Samuel Anthony Alito, Jr. 1) 2) 3) 4) Historical Background of the Supreme Court Prior to John Marshall Debate at Constitutional Convention over structure of courts: state courts v.s. lower federal courts Article III created a Supreme Court and left it to Congress to decide whether to create lower federal courts. Judiciary Act of 1789 – Congress created lower federal courts Number of justices on the Supreme Court fluctuated for the first 70 years, has remained at 9 since 1869. Chief Justice John Marshall, 1801-1835 “That the Constitution has been able to grow and change with the country owes much to John Marshall.” Brian McGinty, The Great Chief Justice Marshall, a dedicated Federalist, noted for his masterful opinions, made the judicial branch a coequal branch of government. Basic Tenets of Marshall’s Federalism 1) supremacy of the nation over the state The rise of nationalism during these years was 2) sanctity of contracts encouraged by Marshall’s decisions and helped 3) protection of property rights check the growing trend of sectionalism. 4) superiority of business over agriculture Establishing the Supreme Court as a Coequal Branch of the Government 1) Strengthened the Supreme Court at the expense of the other federal branches by assuming the power of judicial review (Marbury v. Madison) 2) Expanded federal power at the expense of the states by declaring state laws unconstitutional (Dartmouth v. Woodward), by denying a state the right to tax a federal agency (McCulloch v. Md.), and by upholding a broad interpretation of interstate commerce (Gibbons v. Ogden) 3) Protected the terms of basic business contracts against impairment by state law (Dartmouth), and upheld the loose interpretation of the Constitution’s elastic clause (McCulloch) Marshall’s Great Cases Judicial Review – Marbury v. Madison, 1803 Expansion of Contract Clause – Fletcher v. Peck, 1810; Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 1819 Reaffirmation of Appellate Jurisdiction – Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 1816; Cohens v. Virginia, 1821 Implied Powers and National Supremacy – McCulloch v. Maryland, 1819 Power to Regulate Commerce – Gibbons v. Ogden, 1824 (Marshall’s last great ruling) The Power of Judicial Review Judicial Review is the power to a) determine whether or not laws are in harmony with the provisions of the Constitution, and b) for such laws that are in conflict with the Constitution, to declare them invalid, void, and unconstitutional. **The power of the judiciary to invalidate statutes or government actions when they violate the Constitution is controversial, both as to the authority for the power and the proper manner of its exercise. The Constitution does not expressly authorize federal courts to invalidate government actions that violate the Constitution. This power was created by Marbury v. Madison, 1803. Historical background for judicial review prior to Marbury v. Madison, 1803 State supreme courts had dealt with judicial review prior to the writing of the Constitution: Rutgers vs. Waddington, 1784; Trevett vs. Weeden, 1786-1787; Bayard vs. Singleton, 1787. Alexander Hamilton in Federalist #78 set forth the principle judicial review. The elected representatives of the people, the President and the Congress, would have no authority to interpret the meaning of the Constitution. Only the judges can give a final interpretation of the meaning; only they can determine the limits of power assigned to the various branches of the government. Creation of the Authority for Judicial Review Facts of Marbury v. Madison, 1803: Federalists, realizing they had been badly defeated by the Republicans in the election of 1800, decided to keep the elected Republicans from “ruining the country.” Since Thomas Jefferson was not to take office until March of 1801, the Federalists, who were in control of Congress and the Presidency, decided that it would be a good time to reform the federal court system. Accordingly, they replaced the Judiciary Act of 1789 with a new act, the Judiciary Act of 1801. Its major provisions reduced the size of the Supreme Court from six to five justices and created six new circuit courts with 16 new judgeships. An additional act gave the president authority to appoint a number of justices of the peace for the District of Columbia. The major thrust of this Federalist plan was to give outgoing President Adams a total of 58 new vacancies to fill in the federal court system. The purpose of the appointments was to enable the Federalists to maintain control of the judicial branch of the federal government. Since he was occupied with the task of filling these vacancies until the very end of his term, Adams was accused by the Republicans of making “midnight appointments.” Furious Republicans repealed the Judiciary Act of 1801 and passed the Judiciary Act of 1802 which restored the size of the Supreme Court to six justices and abolished the new judgeships which had been established. William Marbury, appointed justice of the peace in D.C., was confirmed by the Senate and his commission signed March 3, 1801 by Adams. However, his commission was not delivered before Jefferson became president March 4. T.J. ordered his Sec. of State, James Madison, not to deliver the commission. Marbury’s Suit: Marbury filed suit against Madison directly in the Supreme Court and argued that a provision in the Judiciary Act of 1789 authorized the Court to issue a writ of mandamus which would compel Madison to deliver the commission. The Judiciary Act of 1789 said that the Supreme Court had the power to issue such writs “to any courts appointed, or persons holding office, under the authority of the United States.” Court’s Ruling: Unanimous. Chief Justice Marshall, who had viewed the repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801 as an attack on the judicial system itself, had been looking for a way to assert the power of the judiciary which would not seem to be a partisan political move. Marshall went back to the Constitution itself to see what powers it had granted the Supreme Court. Original jurisdiction was given only in cases “affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party.” Marbury was certainly not an ambassador, public minister, or consul, nor did his case involve a state. Neither did it come from a lower court on appeal. Therefore, although what Marbury asked was authorized by federal law, it was not authorized by the Constitution. Marbury had the right to the commission. The court has the right (authority) to review the constitutionality of the executive branch’s conduct, but it could not provide relief to Marbury. 1) Declared a federal law unconstitutional: Marshall concluded Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional in authorizing the matter to be filed originally in the Supreme Court. 2) The Court’s rationale: Art. III prescribed a few instances in which the Supreme Court possesses original jurisdiction – Marbury’s suit was not among them. Therefore, the statute authorizing jurisdiction was inconsistent with the Constitution and invalid. Marshall’s Brilliance 1) Finds a way to avoid confrontation with the executive branch. Had little choice but to deny Marbury. Jefferson would have refused an order to deliver the commission. 2) Marshall strengthened the judiciary’s power by establishing judicial review – articulated a role for the federal courts that survives to this day. Single most important judicial decision in American history: Established the authority of the Supreme Court to review the constitutionality of both presidential and congressional actions. The Constitution imposes limits on government powers and those limits are meaningless unless subject to judicial enforcement. “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” The Supreme Court would not invalidate another act of Congress until 1857 in the Dred Scott case. Fletcher v. Peck, 1810 (contracts, state laws) Yazoo land fraud case – Influenced by bribes, the corrupt Georgia legislature sold land to speculators. The outraged public elected virtually a new legislature at the next election, and the new legislature rescinded the previous sale. The case involved the legality of the sale of a tract of land made before the second legislature rescinded the original transaction. Chief Justice John Marshall wrote the decision. The Georgia legislature could not interfere with a lawfully executed contract. No matter how the original land speculators had obtained the land grant, Fletcher had made a legal, contractual purchase with which the legislature could not interfere. The contract clause of the Constitution overrode the state law. Art. I, Sec. 10, Clause 1 Martin V. Hunter’s Lessee, 1816; Cohens v. Virginia, 1821 (federal appellate jurisdiction over state courts) The case involved vast landholdings of Lord Fairfax, a Virginian, who was loyal to the British crown during the Revolution. During the Revolution, Virginia confiscated all his land and later enacted a law denying an alien the right to inherit property. When the heirs of Lord Fairfax attempted to claim his land after the Revolution, the courts of Virginia ruled that they could not have the property. This created a problem because the U.S. had assured British subjects, after the Revolutionary War, that their property rights would be respected. Getting no satisfaction in the courts of Virginia, the Fairfax family decided to appeal their case to the Sup. Ct. The Court, stating that they had the right to hear the case under Article 3 of the Constitution, overruled the Virginia Court and declared that treaties (Art. VI) and laws of the U.S. took precedence over the laws of Virginia. Some Virginians were in no mood to accept the high court’s decision. The state of Virginia refused to implement the decision, claiming that the Supreme Court did not have the power to hear the case in the first place. This case asserted that the Supreme Court had appellate jurisdiction over state court decisions. Concurrent federal and state jurisdiction did not make the state and federal courts equal, and state judges must decide cases according to “the supreme law of the land.” (Art. VI) Supreme Court appellate jurisdiction of state court cases ensures a uniformity of constitutional decisions. Cohens: The Cohens were convicted for selling lottery tickets in violation of Virginia state law. They claimed that the law was not valid because Congress had permitted the lotteries in D.C. and that the laws of Congress took precedence over the laws of Virginia. The Supreme Court ruled against the Cohens, but the lottery was not the real issue in the case. The real issue was again whether the Supreme Court had the power under the Constitution to hear cases on appeal from state courts. “America has chosen to be, in many respects and to many purposes, a nation; and for all these purposes, her government is complete; to all these objects, it is competent. The people have declared, that in the exercise of all powers given for these objects, it is supreme. It can, then, in effecting these objects, legitimately control all individuals or government within the American territory.” In such a government, Marshall went on to say, the Sup. Ct. must be able to decide if the laws of a state are in conformity with the federal Constitution and laws. Therefore, it must be able to hear appeals from the states. Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 1819 (contracts and state laws, property rights) In 1816 the state legislature of New Hampshire took over Dartmouth College. The board of trustees sued to regain control. Was the original private charter granted in 1769 by royal charter a contract within the meaning of the contract clause of the Constitution? The Court ruled that it was. The charter of a private corporation was protected by the Constitution and could not be altered by the people through their legislature. Art. I, Sec.10 *Encouraged business firms to invest their capital and to rely on the charters of their corporations without fearing the whimsies of state governments. **Daniel Webster handles the case for Dartmouth (alumni). McCulloch v. Maryland, 1819 (implied powers, national supremacy) In 1816 the Second Bank of the U.S. was established by an act of Congress. The B.U.S. was a private bank but acted as an agent of the federal government for the collection of taxes, the transfer of government funds, and the disbursement of money for the government. The B.U.S. set up branches in several states. Maryland, like other states, did not like such competition with its state-chartered banks, and decided to tax all out-of-state banks operating in Maryland. The B.U.S. was taxed an annual fee of $15,000 with a penalty of $500 for each offense of issuing bank notes without paying the tax. The cashier of the B.U.S. bank, James McCulloch, refused to pay the tax in any form and was sued by the state of Maryland. The state courts upheld the state tax law. The B.U.S. carried the case to the Sup. Ct. in 1819. The case raised the question of the constitutionality of the 1791 act of Congress which created the Bank, and the question of whether a state could tax the federal government. Marshall’s opinion supported the loose construction theory of the Constitution and gave a broad interpretation to the last clause of Art. I granting Congress the power to make laws “necessary and proper’ to carry out its delegated powers (Art. I, Sect. 8, Clause 18). “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional.” No state had the right to hinder or control any national institution established within its borders. “The power to tax is the power to destroy.” Gibbons v. Ogden, 1824 (regulation of interstate commerce) In 1807 Robert Fulton developed the first steamboat. The New York legislature gave to Fulton and his partner, Robert Livingston, the exclusive right to operate steamboats on the waters of New York state. These two men licensed to Aaron Ogden the exclusive right to operate a ferry across the Hudson River between New York and New Jersey ports. In the meantime, Congress had licensed Thomas Gibbons to run two steamships between New York and Elizabethtown, New Jersey. Then other states – Connecticut, Georgia, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire, among them—awarded exclusive rights to their own citizens, and kept the ships of other states out of their waters. The nation was in danger of suffering commercial strangulation as bitter antagonisms developed among states. The Supreme Court could do nothing until someone brought up a case. Ogden attempted to prevent Gibbons’ competition, and asked the New York courts to issue a cease and desist order to Gibbons. They supported Ogden, so Gibbons appealed to the Sup. Ct. Specific issue: could a state grant exclusive rights to navigation in waters leading to another state? The Court ruled unanimously it could not. Questions: 1) What is commerce? 2) What is interstate commerce? 3) Have the states any power over interstate commerce? Art. 1, Sec. 8: “The Congress shall have Power to regulate Commerce…among the several States.” There was no question about the power of Congress over interstate commerce. The disagreement was over the interpretation of this commerce clause. Marshall had to accept either a broad or a narrow interpretation of the terms “commerce” and “to regulate.” He chose the former. This decision freed American commerce from rigid restrictions. It guaranteed that all kinds of transportation and communication among the states—including today’s railroads, pipelines, telephone, radio, television, and cable-- could be developed without local interference. John Marshall’s Legacy 1) His repeated invalidations of state statutes defeated states’ rights adherents, making the Court the final arbiter in disputes between states and the central government 2) For a long time, Marshall’s constitutional law served as a check upon the strong popular trend toward state sovereignty and decentralization 3) He insisted that the Constitution was an ordinance of the American people and not a compact of the sovereign states and, therefore, that the U.S. was a sovereign nation and not a mere federation of states. Works Cited James, Leonard F. The Supreme Court in American Life. Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company. 1964. Selakovich, Dan The Supreme Court. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, Inc. 1976. Wright, Benjamin F. The Growth of American Constitutional Law. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1942.