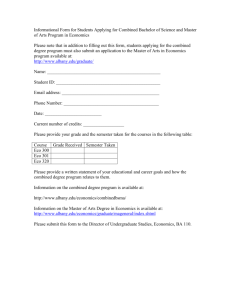

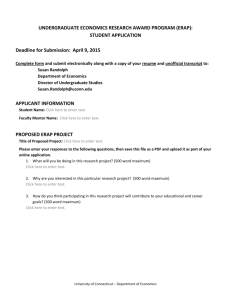

University of Oregon Department of Economics

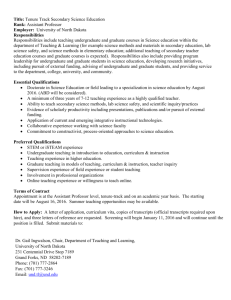

advertisement