The Diplomacy of Woodrow Wilson - LBCC e

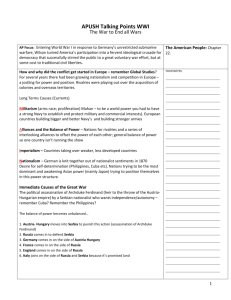

advertisement

The Diplomacy of Woodrow Wilson Prologue: Contemporary American Presidents such as G. H. W. Bush and William Clinton keep talking about a new world order. When they do they sometimes sound Wilsonian. Wilson was the first American theorist of a liberal world order. His dream ended in tragedy, but it outlived its critics. Whether Bush will see his dream order realized remains to be seen. So far, however, he has had a much easier time of it than Wilson. Wilson: A watershed diplomacy. Man and personality. An incredible leader whose career is shot through with irony and folly, perplexity and pain. A protestant moralist and idealist, he attempted to reform the most immoral invention of man: the power system of nation states. The only professor to be president. He had an intellectual primness and gentility. He lacked the personal dynamism, magnetism, and charisma of leaders like T. Roosevelt. Wilson is crucial because he transformed the language about the ends of American diplomacy. He injected foreign policy discussion with a high idealism. He attempted to give to American diplomacy a veneer of lofty goals. It was during his regime that Americans were told their country would never again seize territory in conquest. It was under Wilson that Americans were told they would go to war to Make the World Safe for Democracy. It was under Wilson that America was suppose to remain neutral in word and deed in the face of the slaughter in Europe. It was under Wilson that America was to commit to the principle of self-determination of peoples. Wilson was a master of rhetorical shibbolith. His experience and actions seemed to betray everyone of his high ideals. Consider the following. He entered office committed to "the development of constitutional liberty in the world." But his Mexico intervention shows he practiced destabilization. Self-determination did not extend to the right of peoples of other countries to control their own resources, if those resources were owned by Americans. When war broke out in Europe, he began committed only to protecting the right of neutrals to travel and trade without interference from belligerents. His policies soon allied the US government and economy with the cause of the allies. To Germany, he appeared a crucial belligerent. His policy of neutrality ended requiring war to protect it. He fought the war to ensure that the United States would define the nature of the peace and the character of international relations in the post-war world. His quest for internationalism failed to win the support of neither the Senate, who rejected it, nor the leaders of Europe, who never accepted it in the first place. The man whose personality required that he be right died a bitter and broken man. 2. Four issues dominated Wilson's Foreign Policy during his eight years in office. Intervention in Mexico. Neutrality toward the belligerents from August 1914 to April 1917. His effort to define a "peace without victory" and to implement the 14 points and win passage of America's entry into the League of Nations. Bolshevik Intervention. Mexican Intervention. By any measure Wilson's diplomacy toward the Mexican revolution was ill-informed and ill-advised. In 1911, the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz was ended and a new government under a mystical leader named Francisco Madero took its place. At the time, the US had direct investments totaling $2 billion dollars. President Taft responded by sending US warships to the Gulf. But he reframed from intervening although he was under great pressure from American and English economic interests, especially oil interests to intervene to protect their investments. The Roosevelt Corollary required not less. c. Just prior to Wilson's assumption of the Presidency, Madero was murdered by General Victoriano Huerta, who took his place at the head of the new government. Wilson had a genuine dislike for Huerta, both for the way he seized power, and because he believed Huerta was being supported by the British as a means of continuing to exploit the countries oil resources. His personality demanded that he do something. But what? Initially, he sent an emissary to Huerta informing the leader that if he would fulfill his promise to hold elections, and then step aside, the US government would arrange a loan for Mexico. Huerta promptly embarrassed the President by accusing him of bribery and betrayal of his country. 2. Wilson's response was to announce that Mexico had no government, and to proceed to openly support an opposition. In this case, the so-called Constitutionalist led by Venustiano Carranza. The position invited open tension between Wilson and Huerta. At one point the two countries almost went to war over an incident in which the US flag was insulted. The US briefly occupied Veracruz and Tampico. Opposed by the US and challenged by Carranza, Huerta chose to leave--on a British battleship. 3. Carranza was another matter. He gained office in August 1914. He soon talked openly as a nationalist interested in confronting the issue of foreign control of Mexican resources. 4. To combat this menace, Wilson's Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, began secretly funding Pancho Villa, an opponent of Carranza who represented radical agricultural reform. Carranza came from the landowning elite. The funding arrangement involved permitting Villa to receive funds secretly from the sale of stolen cattle in the US. Why did Lansing allow this. Wilson's Secretary of State explained: The reason for furnishing Villa with an opportunity to obtain funds is this: “We do not wish the Carranza faction to be the only one to deal with in Mexico. Carranza seems so impossible that an appearance, at least, of opposition to him will give us an opportunity to invite a compromise of factions. Wilson wasn't willing to do this.” He cancelled the covert action. That withdrawal of support led Villa to begin attacking US border cities. Before long the US was intervening in Mexico to catch Villa. But this was a side show compared to the real issue. The real issue was this. In early 1917, Carranza pronounced a new constitution that vested subsoil mineral rights in the central government--a nationalization of oil. If foreigners wanted access to Mexican oil, they would have to surrender their "right" to invoke the support of their governments in disputes with the Mexican government-in effect sign a non-intervention agreement. Carranza also announced new regulatory and tax measures on pre-1917 concessions. In taking these actions, Mexico became the first "Third World" trouble spot involving a clash over control of natural resources. Wilson's response to this new situation was to encourage private bankers to offer the Carranza government a loan of $150 million so that the government would not need to nationalize its oil resources. Carranza rejected that offer because it required all foreign properties to be returned. With the US entering the war in Europe, Wilson chose to put the issue aside. Neutrality during WW One. Background to the War. What imperialism did not include during its heyday. Imperialism had not represented a departure from the principle of non-alignment or treaties with foreign powers. A modern navy, yes. Island colonies and naval bases, yes. The US political elite had been willing to imitate European powers in these respects. But not in terms of older tradition of no entangling alliances. The US had remained neutral in face of creation of alliance system by Europeans between 1900 and 1914. That alliance system had created two contending coalitions of power: the Central Powers or Triple Alliance--Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy, and the Allied Powers or Triple Entente--Great Britain, France, and Russia. In July 1914, after years of international crisis and near misses on the way to war, a long period of naval arms race between Britain and German, and a matching period of massive growth in land armies on the part of France, Germany, and Russia, the powder keg exploded. A local assassination of Arch Duke Ferdinand turned into a regional conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. War between these regional powers drew in their alliance allies, Germany and Russia. This turned the war into a continental struggle. Entry of France and Great Britain in support of Russia turned a continental war into a World War. Outbreak of war made non alliance position right. Two Analytical questions. Events leading up to World War I set the stage for the two analytical questions historians of the event must explain. Why did the U.S. reluctantly depart from traditions of neutrality to become a belligerent in 1917? Why did Americans, after getting involved and dictating the outcome, reject the peace treaty which their own president had largely shaped and which presumably justified the sacrifices of the war? c. Public, Administration, and War. 1. Initial reactions true to US tradition. Most Americans horrified at war and relieved US wasn't involved. But they were not a disinterested public. Many hyphenated Americans are partisans of one side or another. Within the Administration a mixed group. - 1. Sec of State William J. Bryan is a near-pacifist. He believed morality, reason, and Christian love, not force, should rule the world. He was shocked by the war. He condemned both sides. He didn't see either side as right. Both sides guilty of wrong-doing. He persuaded Wilson to play the US role as a mediator of the conflict. Get the two sides to peace talks. This led to a fruitless attempt to have two sides spell out their war aims. - 2. National security thinkers. Anti-German, pro-British within administration. They took sides. See Germany as a strategic threat to the US. A long term threat because Germany is autocratic and militaristic. Robert Lansing, Edward House, Ambassadors to Britain and Germany: (Walter Hines Page and James W. Gerard.) They feared the impact a German victory over GB would have on US economic and political interest. Few Americans were thinking in these strategic terms in 1914. - 3. Wilson. Like Bryan in two ways. A moralist, he believed US must be a force for good in world affairs. Also like Bryan, not experienced in foreign affairs. Initially, he leaned toward Bryan's position. He doesn't want to take sides. He wants US to find solution to conflict. 2. Policy. When war broke out in Europe in August 1914 Wilson announced American policy would be one of neutrality in thought and deed. Was Wilson really neutral? He was unable to follow a policy of strict neutrality on finance. Very quickly, the English and French came to dominate US trade. Over the years, German trade and loans totaled about $29 million. Allied trade alone reached $3.2 billion by 1916. A virtually new industry in munitions grew up overnight and the US economy, which had been in a depression, boomed. - 1. So large were allied purchases that Britain and France soon exhausted their ability to purchase supplies using existing assets. Britain was spending 5 million pounds per day, 2 million in the US. - 2. In order for purchases to continue, the allies appealed to Wilson's administration to allow private loans. That appeal was agreed to, although in the spirit of neutrality, Germany could also borrow to pay for purchases. Soon the allies were into US bankers for $2.5 billion. The Germans were in to bankers for $27 million. - 3. The dependency was startling. It clearly tied the fate of the banking system to the success of the allied cause. - 4. The growth of a munitions industry, and the dependence of the allies on US private loans have led some to believe neutrality lost out to profits. These economic relations did make the US a virtual ally of GB and France, neutrality rhetoric to the contrary. But economic dependence doesn't necessary require war. Wilson was also unwilling to follow a policy of strict neutrality in the face of challenges to the rights of neutrals by both the British and Germans. Both engaged in interdiction of US shipping. Britain seized US ships attempting to trade with Germany. This violated international law because only contraband can be seized. Foodstuffs and raw materials are not contraband. Germany sank several foreign ships carrying war materials that included US citizens as passengers. They also sank US ships. Why were the British able to seize ships and the Germans engaged in sinking ships? Because Britain dominated the sea. They used their control of the sea to blockage Europe and try to starve Germany into submission. In order for Germany to combat this strategy of starvation, it was only able to challenge British naval superiority using a new technology called the submarine (U-boat). The U-boat had to remain underwater to be effective. Surfacing meant danger. This meant Germany could not engage in the British practice of stop and seizure. After a series of incidents, between March and August 1915, including the death of 128 Americans on the Lusitiana in May 1915, the Wilson administration debated a threaten of war against Germany. In July 1915, Secretary of State Bryan concluded that Wilson was unfairly singling out the Germans for threat. He resigned and was replaced by Robert Lansing. US then demanded Germany end unrestricted submarine warfare. The Germans agreed to stop submarine warfare. In January 1917, however, Germany forced the issue because, in their analysis of the problem, the US had objectively become a logistical arms of the allied effort, and continued acquiescence to the situation would result in slow defeat. Better to revive submarine warfare, and try to knock out the British before the US can get fully into the struggle. Wilson formally broke diplomatic relations with Germany in February 1917. Between February and April 1917, the Germans sank five US merchant vessels. The rest is history. On April 6, 1917, the US declared war. The issue of submarine warfare was clearly a catalyst for war. We have to ask, had the Germans not resumed submarine warfare, would Wilson have sought a declaration. What about the strategic issue? In January 1918, Germany contacted Mexico with an alliance against the US in return for a war of conquest. Germany's actions did provide evidence strategic interests were also a consideration for some.5. Peace Without Victory and the New Liberal Internationalism. Why did Americans, after getting involved and dictating the outcome, reject the peace treaty which their own president had largely shaped and which presumably justified the sacrifices of the war? Wilson's dream of a liberal order. American intervention and decisive role in outcome of war created a golden opportunity for US to shape the peace settlement at the end of the war. His 14 points gives us a definition of what would be the new world order. The 14 points. 1. End to secret diplomacy. Secret treaties had been entered into before the war by the allies. These treaties had carved up the choicest possessions of the Germans. Wilson's proposal put this arrangement in jeopardy. 2. Freedom on the High Seas. The British rejected this ideal. The allies retained complete liberty as regards freedom of the seas. 3. Removal of economic barriers between nations. This conflicted with the desire to impose a reparations penalty on the Germans. 4. Reduction of armaments. Totally unenforceable. 5. Adjustment of colonial claims in the interests of both the inhabitants and powers concerned. Versailles allowed the allies to become trustees of the conquered territories under a mandate from the League of Nations. This represented a form of thinly disguised imperialism. 6. Restoration of Russia and her welcome into the society of nations. Did not happen. Instead Wilson intervened with British and French to topple the communist regime. 7. The self-determination principles (7-13). All compromised at Versailles. 8. The 14th Point: A League of Nations. The most important. A partial success. Accepted at Versailles. Wilson's conception: the League would replace the old system of Balance of Power and competition with a new international system that would proceed to resolve all the shortfalls done at Versailles. The international system would become the forum for cooperative action by all the democracies. Through it permanent justice and amity would be secured. The 14 points and the Versailles Treaty. 1. Highly idealistic. But not impractical. Wilson was very well prepared for Paris. His principles, like self-determination, were realistic. But Wilson was unable to prevent a harsh and punitive treaty against Germany. Treatment of German violated many of Wilson's principles, but he could not persuade French, who were obsessed with their own security. Consequently, German self- determination is violated and Germany was pinned with reparations. ($33B). Germany was also disarmed, but no one else was. 3. Wilson gave in to preserve the League. Fate of the treaty. Wilson returned in July 1919. Much had changed. His political position had deteriorated. The GOP had taken control of both houses of Congress in the 1918 bi-elections by a slim margin, 49-47 in senate. That meant the treaty would have to pass a Congress now controlled by the GOP. GOP campaign for heightened nationalism. The nation was entering a growing mood of apathy and hostility. Pre-war isolationism revived. German-Americans denounced the treaty as harsh. Liberals denounced the compromises. Senatorial opinion. 14 GOP irreconcilables. Dead set against superstate. Extreme nationalists. Also personally hate Wilson. Mild reservationists. Liberal GOP. Small change. Strong reservationists. Don't like article X of the treaty. Article X called for US to uphold independence of other states. This was too much an infringement on Congressional power. Power to declare war and make peace compromised. Lodge: Don't let US be controlled by League. But Wilson and liberal Democrats were strong internationalists. They insisted US must make wholehearted commit to collective security. Given the strength of the GOP, in retrospect it appears Wilson should have compromised. He refused. Congress won't go along. The vote on the treaty without change went down 38 to 53. The vote on the treaty with a series of reservations added was also defeated 39 to 55. Wilson directed his Democrats to oppose any change perferring to blame the GOP than get the treaty passed. This stalemate continued into March 1920, when a slightly modified treaty, still with reservations, was again defeated by the Democrats, under Wilson's direction, 49 to 35. 3. Outcome. League approval became a partisan football. Treaty could have been approved, but both GOP and Democrats were guilty of playing politics. When US entry was blocked by the senate, the League of Nations became another forum for the perpetuation of nationalistic interests. The League, therefore, did not represent the vital change Wilson hoped for. As one historian has put it, the League became "simply an attempt to give organization to the old chaos." (Richard Hofstadter). The Bolshevik Revolution. Issue: In March 1917, the Czarist Government in Russia under Tsar Nicholas was forced to abdicate as a result of the disastrous defeats the government had suffered at the hands of the Germans. The revolutionaries included liberal, socialist and communist opponents of the Regime. A Liberal provisional government was established under the leadership of Alexander Kerensky. Wilson's government was the first to recognize the new regime. But Kerensky made the mistake of attempting to continue the war. This made his government ripe for a coup. In November 1917, the provisional government in turn was overthrown in a violent revolution lead by Vladimir Lenin and the Bolshevik Party. What was Wilson's policy? Initially, he had rejoiced at the liberal revolution because he believed democracy was at hand in Russia. He attitude was widely shared by the interested American public. That enthusiasm came to an abrupt halt when the Bolsheviks seized power. Wilson's attitude toward the Bolsheviks was one of instant hostility. He was anti-Bolshevik in principal because their beliefs represented a threat to democracy, liberty and freedom as Americans defined these terms. He was also hostile to the Bolsheviks because they threatened to take Russia out of the war. This latter concern was real. In March 1918, Lenin signed a treaty with Germany ending Russian action in World War One. He justified the action with the argument that the war was a capitalist war which workers had no stake in. Lenin then proceeded to deeply embarrass and antagonize the Allied leadership. For one thing, he publicized the secret treaties the Russians, French, and Britain had entered into for the purpose of carving up the German empire. For another, he publicly denounced the West's capitalist leadership in called upon workers throughout the world to overthrow capitalism and join the Russian communists in a new socialist order. Abortive attempts were tried in Germany and Hungary in 1919. In the summer of 1918, Civil War broke out in Russia. The British and French allies were eager to intervene in the civil war on the side of the forces fighting the communists. To justify their action, however, they explained they only wanted to place troops in Russia to reestablish a second front using the Japanese and going through Siberia. The excuse for this action was the rescue of two divisions of Czechoslovakian troops entrained eastward on the Trans-Siberian railroad to Vladivostok. Wilson was suspicious of their motives. He feared that the British and French had made a deal with the Japanese to partition Russia and turn over part of the country to Japan. In addition, the British and French proceeded to land troops at Arcangel and Mermanst between July and August 1918. The Japanese entered Russia with 70,000 troops. They intervened in Siberia. The Japanese action seemed to confirm Wilson's suspicion of Japanese ambitions in the Far East. The Japanese would remain in Siberia until 1922. 6. In July 1918, the US joined the British, French, and Japanese by landing 7,000 troops at Vladivostok. US troops remained in Russia for two years. 7. Why did Wilson intervene? He was anti-bolshevik? He distrusted the other allies? He wanted a second front to fight Germany? Reasons may be less important than effects: The US actions add to the suspicion of the west held by the communist leadership. A legacy of distrust follows. The US was among the last nations to recognize the USSR in 1933.