A Study of Focal Sentences in Professional Writing

advertisement

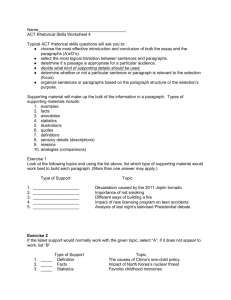

A A SSttuuddyy ooff FFooccaall SSeenntteenncceess iinn PPrrooffeessssiioonnaall W Wrriittiinngg —by Dr. Ed Vavra at KISSGrammar.org August 23, 2014 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Two-Paragraph Examples ....................................................................................... 2 1. From Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy (22-23)............... 2 2. From H. G. Wells’ The Outline of History (Vol. 1: 222-224) ........................ 3 Multi-Paragraph Examples ..................................................................................... 5 1. From Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy (291-3)............... 5 Focal Sentences within Focal Sentences................................................................. 6 1. From H. G. Wells’ The Outline of History (Vol. 1: 222-224) ........................ 6 2. From H. G. Wells’ The Outline of History (Vol. 1: 336-337) ...................... 12 Introduction Many of my students have told me that they have been taught how to write a five paragraph essay—with a thesis and topic sentences. Many others do not remember that teaching, and some who do still cannot define a topic sentence. Topic sentences present the main idea of a paragraph or paragraphs, usually in the first sentence. A “focal sentence,” on the other hand, is a tool for organizing longer papers. A “focal sentence” is mid-way between a “thesis” (the main idea of the paper) and a “topic sentence” (the main idea of a paragraph or paragraphs. In effect, a focal sentence introduces (and thus lets the reader be prepared for) two or more related topics. This document is a collection of examples from published writing. So that you can see the transitions (or the lack of them), each example is preceded by the paragraph before it and the paragraph after it. Focal sentences are in red; topic sentences, in blue, and sentences that function as both are in brown. Two-Paragraph Examples Simple examples consist of two paragraphs. The focal sentence is the first sentence in the first paragraph. It is immediately followed by the topic sentence for that paragraph. The next paragraph begins with the second topic sentence that is covered by the focal sentence. 1. From Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy (2223) London: GEORGE ALLEN AND UNWIN LTD. 1946,47. [This text is available on the Internet Archive: https://archive.org// ] From Chapter 1 – “The Rise of Greek Civilization” The early development of civilization in Egypt and Mesopotamia was due to the Nile, the Tigris, and the Euphrates, which made agriculture very easy and very productive. The civilization was in many ways similar to that which the Spaniards found in Mexico and Peru. There was a divine king, with despotic powers; in Egypt, he owned all the land. There was a polytheistic religion, with a supreme god to whom the king had a specially intimate relation. There was a military aristocracy, and also a priestly aristocracy. The latter was often able to encroach on the royal power, if the king was weak or if he was engaged in a difficult war. The cultivators of the soil were serfs, belonging to the king, the aristocracy, or the priesthood. There was a considerable difference between Egyptian and Babylonian theology. The Egyptians were preoccupied with death, and believed that the souls of the dead descend into the underworld, where they are judged by Osiris according to the manner of their life on earth. They thought that the soul would ultimately return to the body; this led to mummification and to the construction of splendid tombs. The pyramids were built by various kings at the end of the fourth millennium B.C. and the beginning of the third. After this time, Egyptian civilization became more and more stereotyped, and religious conservatism made progress impossible. About 1800 B.C. Egypt was conquered by Semites named Hyksos, who ruled the country for about two centuries. They left no permanent mark on Egypt, but their presence there must have helped to spread Egyptian civilization in Syria and Palestine. Babylonia had a more warlike development than Egypt. At first, the ruling race were not Semites, but "Sumerians," whose origin is unknown. They invented cuneiform writing, which the conquering Semites took over from them. There was a period when there were various independent cities which fought with each other, but in the end Babylon became supreme and established an empire. The gods of other cities became subordinate, and Marduk, the god of Babylon, acquired a position like that later held by Zeus in the Greek pantheon. The same sort of thing had happened in Egypt, but at a much earlier time. The religions of Egypt and Babylonia, like other ancient religions, were originally fertility cults. The earth was female, the sun male. The bull was usually regarded as an embodiment of male fertility, and bull-gods were common. In Babylon, Ishtar, the earthgoddess, was supreme among female divinities. Throughout western Asia, the Great Mother was worshipped under various names. When Greek colonists in Asia Minor found temples to her, they named her Artemis and took over the existing cult. This is the origin of “Diana of the Ephesians.” Christianity transformed her into the Virgin Mary, and it was a Council at Ephesus that legitimated the title “Mother of God” as applied to Our Lady. 2. From H. G. Wells’ The Outline of History (Vol. 1: 222-224) Revised by Raymond Postgate. N.Y: Garden City, 1961. p. 419 [These paragraphs are the conclusion of Section 1 of Chapter 28. The chapter is primarily about Christianity. Section 1 (about the Jews) serves as an introduction to it. In the Newnes edition (London, 1920, p. 355), the two subdivisions with the focal sentence are all in one paragraph.] Throughout a history of five centuries of war and civil commotion between the return from captivity and the destruction of Jerusalem, certain constant features of the Jews persisted. He remained obstinately monotheistic; he would have none other gods but the one true God. In Rome, as in Jerusalem, he stood out manfully against the worship of any god-Caesar. And to the best of his ability he held to his covenants with his God. No graven images could enter Jerusalem; even the Roman standards with their eagles had to stay outside. Two divergent lines of thought are traceable in Jewish affairs during these five hundred years. On the right, so to speak, are the high and narrow Jews, the Pharisees, very orthodox, very punctilious upon even the minutest details of the law, intensely patriotic and exclusive. Jerusalem on one occasion fell to the Seleucid monarch Antiochus IV because the Jews would not defend it on the Sabbath day, when it is forbidden to work; and it was because the Jews made no effort to destroy his siege train on the Sabbath that Pompey the Great was able to take Jerusalem. But against these narrow Jews were pitted the broad Jews, the Jews of the left, who were Hellenizers, among whom are to be ranked the Sadducees, who did not believe in immortality. These latter Jews, the broad Jews, were all more or less disposed to mingle with and assimilate themselves to the Greeks and Hellenized peoples about them. They were ready to accept proselytes, and so to share God and his promise with all mankind. But what they gained in generosity they lost in rectitude. They were the worldlings of Judea. We have already noted how the Hellenized Jews of Egypt lost their Hebrew, and had to have their Bible translated into Greek. In the reign of Tiberius Caesar a great teacher arose out of Judea who was to liberate the intense realization of the righteousness and unchallengeable oneness of God and of man’s moral obligation to God, which was the strength of orthodox Judaism, from that greedy and exclusive narrowness with which it was so extraordinarily intermingled in the Jewish mind. This was Jesus of Nazareth, the seed rather than the founder of Christianity. [Note how the last paragraph creates a transition by referring to “a great teacher arouse out of Judea” who will challenge the views described in the preceding paragraphs.] Multi-Paragraph Examples 1. From Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy (291-3) London: GEORGE ALLEN AND UNWIN LTD. 1946,47. [This text is available on the Internet Archive: https://archive.org// ] [This example has a short focal paragraph. Focal paragraphs can be longer than this example—they can even be several paragraphs long. I used to have students write a short paper on two issues in the debate about Creationism and Evolution. One issue is the fossil record. When I asked the students what the fossil record is, most of them had no idea. Therefore, to write a meaningful paper, they would have to explain the fossil record (in a focal paragraph) before they wrote paragraphs on what each side had to say about the topic. This example is also more complex in that the focal paragraph is followed by two paragraphs on the theory of knowledge, and then by one on “natural law.” Because this is at the end of the chapter, I had no following paragraph to include.] The End of Chapter 28 – “Stoicism” (291-3) There is, in fact, an element of sour grapes in Stoicism. We can’t be happy, but we can be good; let us therefore pretend that, so long as we are good, it doesn’t matter being unhappy. This doctrine is heroic, and, in a bad world, useful; but it is neither quite true nor, in a fundamental sense, quite sincere. Although the main importance of the Stoics was ethical, there were two respects in which their teaching bore fruit in other fields. One of these is theory of knowledge; the other is the doctrine of natural law and natural rights. In theory of knowledge, in spite of Plato, they accepted perception; the deceptiveness of the senses, they held, was really false judgment, and could be avoided by a little care. A Stoic philosopher, Sphaerus, an immediate disciple of Zeno, was once invited to dinner by King Ptolemy, who, having heard of this doctrine, offered him a pomegranate made of wax. The philosopher proceeded to try to eat it, whereupon the king laughed at him. He replied that he had felt no certainty of its being a real pomegranate, but had thought it unlikely that anything inedible would be supplied at the royal table. In this answer he appealed to a Stoic distinction, between those things which can be known with certainty on the basis of perception, and those which, on this basis, are only probable. On the whole, this doctrine was sane and scientific. Another doctrine of theirs in theory of knowledge was more influential, though more questionable. This was their belief in innate ideas and principles. Greek logic was wholly deductive, and this raised the question of first premisses. First premisses had to be, at least in part, general, and no method existed of proving them. The Stoics held that there are certain principles which are luminously obvious, and are admitted by all men; these could be made, as in Euclid’s Elements, the basis of deduction. Innate ideas, similarly, could be used as the starting-point of definitions. This point of view was accepted throughout the Middle Ages, and even by Descartes. The doctrine of natural right, as it appears in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, is a revival of a Stoic doctrine, though with important modifications. It was the Stoics who distinguished jus naturale from jus gentium. Natural law was derived from first principles of the kind held to underlie all general knowledge. By nature, the Stoics held, all human beings are equal. Marcus Aurelius, in his Meditations, favours “a polity in which there is the same law for all, a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed.” This was an ideal which could not be consistently realized in the Roman Empire, but it influenced legislation, particularly in improving the status of women and slaves. Christianity took over this part of Stoic teaching along with much of the rest. And when at last, in the seventeenth century, the opportunity came to combat despotism effectually, the Stoic doctrines of natural law and natural equality, in their Christian dress, acquired a practical force which, in antiquity, not even an emperor could give to them. Focal Sentences within Focal Sentences 1. From H. G. Wells’ The Outline of History (Vol. 1: 222-224) London: Newnes. 1920. [Because of the complexity of the organization (and the importance of the ideas), I’ve included all of section #8 of the Chapter on “Greek Thought, Literature, and Art.” (I have omitted the footnotes.) I’ve also numbered the eleven paragraphs because the selection illustrates, so to speak, a focal sentence within a larger focal sentence. The first sentence of the first paragraph sets up a contrast between the Greek classics and modern men. The second paragraph develops that idea as comparisons between them and us. The third paragraph is a focal paragraph that introduces the “three barriers.” Paragraph four begins with a topic sentence that introduces the first barrier— obsession with the city state. That idea is continued in five, after which we get (in six) a topic sentence that names the second “barrier”—slavery. Paragraph seven begins with a topic sentence announcing the third “barrier”—“want of knowledge.” Paragraph eight brings us back to “Our world today” with a nice transition from their “want of knowledge” to our “immense accumulations of knowledge.” Eight, nine, and ten then suggest how we should reflect on the differences between them and us. Wells then ends this section (which explains why the Greeks failed) with a transition to the next chapter (paragraph 11)—which will be about “one futile commencement, one glorious shattered [Greek] beginning of human unity.” A paragraph outline of this section would look something like the following: 1-2 I. How we should read the Greek classics 3 II. Three barriers set in the Greek mind 4-5 A. The city as the ultimate state 6 B. The institution of domestic slavery 7 C. Want of Knowledge 8-10 III. What “our world” should learn from the Greeks 11 IV. (Conclusion) Transition to next chapter 1. If the Greek classics are to be read with any benefit by modern men, they must be read as the work of men like ourselves. Regard must be had to their traditions, their opportunities, and their limitations. There is a disposition to exaggeration in all human admiration; men will treat the rough notes of Thucydides; or Plato for work they never put in order as miracles of style, and the errors of their transcribers as hints of unfathomable mysteries; most of our classical texts are very much mangled, and all were originally the work of human beings in difficulties, living in a time of such darkness and narrowness of outlook as makes our own time by comparison a time of dazzling illumination. What we shall lose in reverence by this familiar treatment, we shall gain in sympathy for that group of troubled, uncertain, and very modern minds. The Athenian writers were, indeed, the first of modern men. They were discussing questions that we still discuss; they began to struggle with the great problems that confront us to-day. Their writings are our dawn. 2. They began an inquiry, and they arrived at no solutions. We cannot pretend to-day that we have arrived at solutions to most of the questions they asked. The mind of the Hebrews, as we have already shown, awoke suddenly to the endless miseries and disorders of life, saw that these miseries and disorders were largely due to the lawless acts of men, and concluded that salvation could come only through subduing ourselves to the service of the one God who rules heaven and earth. The Greek, rising to the same perception, was not prepared with the same idea of a patriarchal deity; he lived in a world in which there was not God but the gods; if perhaps he felt that the gods themselves were limited, then he thought of Fate behind them, cold and impersonal. So he put his problem in the form of an enquiry as to what was right living, without any definite correlation of the right-living man with the will of God. . . . To us, looking at the matter from a standpoint purely historical, the common problem can now be presented in a form that, for the purposes of history, covers both the Hebrew and Greek way of putting it. We have seen mankind rising out of the unconsciousness of animals to a continuing racial selfconsciousness, realizing the unhappiness of its wild diversity of aims, realizing the inevitable tragedy of individual self-seeking, and feeling their way blindly towards some linking and subordinating idea to save them from the pains and accidents of mere individuality. The gods, the god-king, the idea of the tribe, the idea of the city; here are ideas that have claimed and held for a time the devotion of men, ideas in which they have a little lost their individual selves and escaped to the realization of a life larger and more enduring. Yet, as their wars and disasters prove, none of these greater ideas were yet great enough. The gods failed to protect, the tribe proved itself vile and cruel, the city ostracized one’s best and truest friends, the god-king made a beast of himself. . . . 3. As we read over the speculative literature of this great period of the Greeks, we realize three barriers set about the Greek mind, from which it rarely escapes, but from which we now perhaps are escaping. 4. The first of these limitations is the obsession of the Greek mind by the idea of the city as the ultimate state. In a world in which empire had followed empire, each greater than its predecessor, in a world through which men and ideas drive ever more loosely and freely, in a world visibly unifying even then, the Greeks, because of their peculiar physical and political circumstances, were still dreaming impossibly of a compact little city state, impervious to outer influences, valiantly secure against the whole world. Plato’s estimate of the number of citizens in a perfect state varied between 1,000 (the Republic) and 5,040 (the Laws) citizens. This state was to go to war and hold its own against other cities of the same size. And this was not a couple of generations after the hosts of Xerxes had crossed the Hellespont! 5. Perhaps these Greeks thought the day of world empires had passed for ever, whereas it was only beginning. At the utmost their minds reached out to alliances and leagues. There must have been men at the court of Artaxerxes thinking far away beyond these little ideas of the rocky creek, the island, and the mountain-encircled valley. But the need for unification against the greater powers that moved outside the Greek-speaking world, the Greek mind disregarded wilfully. These outsiders were barbarians, not to be needlessly thought about; they were barred out now from Greece for ever. One took Persian money; everybody took Persian money; what did it matter? Or one enlisted for a time in their armies (as Xenophon did) and hoped for his luck with a rich prisoner. Athens took sides in Egyptian affairs, and carried on minor wars with Persia, but there was no conception of a common policy or a common future for Greece. . . . Until at last a voice in Athens began to shout “Macedonia!” to clamour like a watch-dog, “Macedonia!” This was the voice of the orator and demagogue, Demosthenes; hurling warnings and threats and denunciations at King Philip of Macedon, who had learnt his politics not only from Plato and Aristotle, but also from Isocrates and Xenophon, and from Babylon and Susa, and who was preparing quietly, ably, and steadfastly to dominate all Greece, and through Greece to conquer the known world. . . . 6. There was a second thing that cramped the Greek mind, the institution of domestic slavery. Slavery was implicit in Greek life; men could conceive of neither comfort nor dignity without it. But slavery shuts off one’s sympathy not only from a class of one’s fellow subjects; it puts the slave-owner into a class and organization against all stranger men. One is of an elect tribe. Plato, carried by his clear reason and the noble sanity of his spirit beyond the things of the present, would have abolished slavery; much popular feeling and the New Comedy were against it; the Stoics and Epicureans, many of whom were slaves, condemned it as unnatural, but finding it too strong to upset, decided that it did not affect the soul and might be ignored. With the wise there was no bound or free. To the matter-of-fact Aristotle, and probably to most practical men, its abolition was inconceivable. So they declared that there were in the world men “naturally slaves.” . . . 7. Finally, the thought of the Greeks was hampered by a want of knowledge that is almost inconceivable to us to-day. They had no knowledge of the past of mankind at all; at best they had a few shrewd guesses. They had no knowledge of geography beyond the range of the Mediterranean basin and the frontiers of Persia. We know far more to-day of what was going on in Susa, Persepolis, Babylon, and Memphis in the time of Pericles than he did. Their astronomical ideas were still in the state of rudimentary speculations. Anaxagoras, greatly daring, thought the sun and moon were vast globes, so vast that the sun was probably “as big as all the Peloponnesus.” The forty-seventh proposition of the first book of Euclid was regarded as one of the supreme triumphs of the human mind. Their ideas in physics and chemistry were the results of profound cogitation; it is wonderful that they did guess at atomic structure. One has to remember their extraordinary poverty in the matter of experimental apparatus. They had coloured glass for ornament, but no white glass; no accurate means of measuring the minor intervals of time, no really efficient numerical notation, no very accurate scales, no rudiments of telescope or microscope. A modern scientific man dumped down in the Athens of Pericles would have found the utmost difficulty in demonstrating the elements of his knowledge, however crudely, to the men he would have found there. He would have had to rig up the simplest apparatus under every disadvantage, while Socrates pointed out the absurdity of seeking Truth with pieces of wood and string and metal such as small boys use for fishing. And he would have been in constant danger of a prosecution for impiety. 8. Our world to-day draws upon relatively immense accumulations of knowledge of fact. In the age of Pericles scarcely the first stone of our comparatively tremendous cairn of things recorded and proved had been put in place. When we reflect upon this difference, then it ceases to be remarkable that the Greeks, with all their aptitude for political speculation, were blind to the insecurities of their civilization from without and from within, to the necessity for effective unification, to the swift rush of events that was to end for long ages these first brief freedoms of the human mind. 9. It is not in the results it achieved, but in the attempts it made that the true value for us of this group of Greek talkers and writers lies. It is not that they answered questions, but that they dared to ask them. Never before had man challenged his world and the way of life to which he found his birth had brought him. Never had he said before that he could alter his conditions. Tradition and a seeming necessity had held him to life as he had found it grown up about his tribe since time immemorial. Hitherto he had taken the world as children still take the homes and habits in which they have been reared. 10. So in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. we perceive, most plainly in Judea and in Athens, but by no means confined to those centres, the beginnings of a moral and an intellectual process in mankind, an appeal to righteousness and an appeal to the truth from the passions and confusions and immediate appearances of existence. It is like the dawn of the sense of responsibility in a youth, who suddenly discovers that life is neither easy nor aimless. Mankind is growing up. The rest of history for three and twenty centuries is threaded with the spreading out and development and interaction and the clearer and more effective statement of these main leading ideas. Slowly more and more men apprehend the reality of human brotherhood, the needlessness of wars and cruelties and oppression, the possibilities of a common purpose for the whole of our kind. In every generation thereafter there is the evidence of men seeking for that better order to which they feel our world must come. But everywhere and wherever in any man the great constructive ideas have taken hold, the hot greeds, the jealousies, the suspicions and impatience that are in the nature of every one of us, war against the struggle towards greater and broader purposes. The last twenty-three centuries of history are like the efforts of some impulsive, hasty immortal to think clearly and live rightly. Blunder follows blunder; promising beginnings end in grotesque disappointments; streams of living water are poisoned by the cup that conveys them to the thirsty lips of mankind. But the hope of men rises again at last after every disaster. . . . 11. We pass on now to the story of one futile commencement, one glorious shattered beginning of human unity. There was in Alexander the Great knowledge and imagination, power and opportunity, folly, egotism, detestable vulgarity, and an immense promise, broken by the accident, of his early death while men were still dazzled |by its immensity. 2. From H. G. Wells’ The Outline of History (Vol. 1: 336-337) London: Newnes. 1920. [These paragraphs are the last in section 2 of Chapter 27 (“On Rome at its Zenith”), so the final paragraph serves both as a subdivision and a transition to the next section. Note how the sentence (in brown) serves both as a topic within the “three things” and as a focal sentence introducing the discussion of the “new religious movements.”] The world, it is evident, was not progressing during these two centuries of Roman prosperity. But was it happy in its stagnation? There are signs of a very Arch of Septimius Severus in the Forum in Rome [From page 336] unmistakable sort that the great mass of human beings in the empire, a mass numbering something between a hundred and a hundred and fifty millions, was not happy, was probably very acutely miserable, beneath its outward magnificence. True there were no great wars and conquests within the empire, little of famine or fire or sword to afflict mankind; but, on the other hand, there was a terrible restraint by government, and still more by the property of the rich, upon the free activities of nearly everyone. Life for the great majority who were neither rich nor official, nor the womankind and the parasites of the rich and official, must have been laborious, tedious, and lacking in interest and freedom to a degree that a modern mind can scarcely imagine. Three things in particular may be cited to sustain the opinion that this period was a period of widespread unhappiness. The first of these is the extraordinary apathy of the population to political events. They saw one upstart pretender to empire succeed another with complete indifference. Such things did not seem to matter to them; hope had gone. When presently the barbarians poured into the empire, there was nothing but the legions to face them. There was no popular uprising against them at all. Everywhere the barbarians must have been outnumbered if only the people had resisted. But the people did not resist. It is manifest that to the bulk of its inhabitants the Roman Empire did not seem to be a thing worth fighting for. To the slaves and common people the barbarian probably seemed to promise more freedom and less indignity than the pompous rule of the imperial official and grinding employment by the rich. The looting and burning of palaces and an occasional massacre did not shock the folk of the Roman underworld as it shocked the wealthy and cultured people to whom we owe such accounts as we have of the breaking down of the imperial system. Great numbers of slaves and common people probably joined the barbarians, who knew little of racial or patriotic prejudices, and were openhanded to any promising recruit. No doubt in many cases the population found that the barbarian was a worse infliction even than the tax-gatherer and the slave-driver. But that discovery came too late for resistance or the restoration of the old order. And as a second symptom that points to the same conclusion that life was hardly worth living for the poor and the slaves and the majority of people during the age of the Antonines, we must reckon the steady depopulation of the empire. People refused to have children. They did so, we suggest, because their homes were not safe from oppression, because in the case of slaves there was no security that the husband and wife would not be separated, because there was no pride nor reasonable hope in children any more. In modern states the great breeding-ground has always been the agricultural countryside where there is a more or less secure peasantry; but under the Roman Empire the peasant and the small cultivator was either a worried debtor, or he was held in a network of restraints that made him a spiritless serf, or he had been ousted altogether by the gang production of slaves. A third indication that this outwardly flourishing period was one of deep unhappiness and mental distress for vast multitudes, is to be found in the spread of new religious movements throughout the population. We have seen how in the case of the little country of Judea a whole nation may be infected by the persuasion that life is unsatisfactory and wrong, and that something is needed to set it right. The mind of the Jews, as we know, had crystallized about the idea of the Promise of the One True God and the coming of a Saviour or Messiah. Rather different ideas from these were spreading through the Roman Empire. They were but varying answers to one universal question: “What must we do for salvation?” One frequent and natural consequence of disgust with life as it is, is to throw the imagination forward to an after-life, which is to redeem all the miseries and injustices of this one. The belief in such compensation is a great opiate for present miseries. Egyptian religion had long been saturated with anticipations of immortality, and we have seen how central was that idea to the cult of Serapis and Isis at Alexandria. The ancient mysteries of Demeter and Orpheus, the mysteries of the Mediterranean race, revived and made a sort of theocrasia with these new cults. A second great religious movement was Mithraism, a development of Zoroastrianism, a religion of very ancient Aryan origin, traceable back to the Indo-Iranian people before they split into Persians and Hindus. We cannot here examine its mysteries in any detail. Mithras was a god of light, a Sun of Righteousness, and in the shrines of the cult he was always represented as slaying a sacred bull whose blood was the seed of life. Suffice it that, complicated with many added ingredients, this worship of Mithras came into the Roman Empire about the time of Pompey the Great, and began to spread very widely under the Caesars and Antonines. Like the Isis religion, it promised immortality. Its followers were mainly slaves, soldiers, and distressed people. In its methods of worship, in the burning of candles before the altar and so forth, it had a certain superficial resemblance to the later developments of the ritual of the third great religious movement in the Roman world, Christianity. Christianity also was a doctrine of immortality and salvation, and it too spread at first chiefly among the lowly and unhappy. Christianity has been denounced by modem writers as a “slave religion.” It was. It took the slaves and the downtrodden, and it gave them hope and restored their self-respect, so that they stood up for righteousness like men and faced persecution and torment. But of the origins and quality of Christianity we will tell more fully in a later chapter.