2BOrNot2BCOMM

advertisement

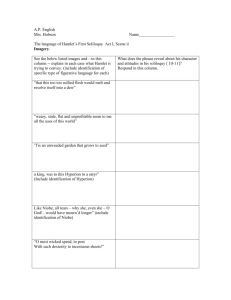

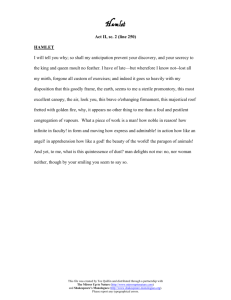

Reaching for “the Rub”: A Commentary on Hamlet’s “To Be or Not to Be” Soliloquy Arguably the most well-known and oft-quoted passage in all of Shakespeare, Hamlet III.i.56-88 contains words which may have earned Prince Hamlet his soubriquet, “the melancholy Dane.” Consider the plethora of reasons for Hamlet’s agonized sadness: in Act I, he mourns his father’s passing, witnesses in shocked revulsion his mother’s “o’er-hasty marriage” to his uncle, acquiesces to his uncle/step-father/king’s decree that he not return to his studies in Wittenburg, suffers shame at Denmark’s vulgar revelries, ponders his own “too, too solid/sullied flesh,” and, finally, is spurred to revenge by the threatening and mournful ghost of his father. As if those causes for despair were not sufficient, in Act II, Ophelia severs their relationship at her father and brother’s behest, his friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern betray him, and Hamlet understandably feels imprisoned in Denmark by the strumpet fortune. As Act III opens, King Claudius and Polonius “bestow” themselves so that they can spy on Hamlet as he “affronts” Ophelia. Although the passage is a soliloquy, the possibility remains that Hamlet may very well know of their hidden presence. In this pained philosophical expression of the quandary of human misery, Shakespeare makes use of rich and erratic language that mirrors Hamlet’s tortured state of mind. The soliloquy, as Hamlet’s private expressions so often are, is labored, passionate, disjointed, and laden with elaborately punctuated mood shifts. The paradox of the opening line—“to be or not to be”—is followed by a dash indicating both pause and continuity, as the sufferer’s mind sets forth the central question. “To sleep”—no more: here the dash reveals Hamlet’s sudden impatience with the idea that death is a sleep. In reality, when one is dead, one truly sleeps “no more.” Then comes the long, long list of life’s miseries: “th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, the pangs of despised love. . . .” The rolling succession of phrases builds to a crescendo before culminating in the idea of “quietus” with a “bare bodkin.” The mood of suicidal despair is transformed into a pained questioning: “Who would fardels bear?” The question of the fear of death resolves itself, however, in the solemn pronouncement that lofty plans are turned “awry and lose the name of action”—a final mood shift suggesting resignation and hopelessness. Like the soliloquy itself, the currents of great enterprise shift and dissipate, as Hamlet’s intentions have and will throughout the play. Despite its erratic style, however, the passage is held together by Hamlet’s skill in logic and formal argument: he is openly considering the journey of death as a rational possibility. From his opening statement of “the question,” to his whether/or construction as he describes the choice between passive suffering or active opposition to life’s vicissitudes, Hamlet employs the stylistic tricks of logical argument: contrast (acceptance or opposition), analogy (death as a sleep), cause-and-effect considerations (that give him “pause”), parallelism (. . . the law’s delay, the insolence of office. . .), rhetorical questions (what might make one “bear those ills we have [rather] than fly to others that we know not of?”) The entire soliloquy takes on the structure of a formal, legal argument as Hamlet brings his powerful, highly educated, and contemplative intellect to bear on the stark question of his own existence. Though the central question may be stark, the soliloquy’s figurative language is exceedingly rich—especially in its paradoxical evocation of the desire for and fear of death. “The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” suggest a violent hunting down of the tragic hero by a cruel fate. The mixed metaphor of “tak(ing) arms against a sea of troubles” creates a picture of the hero hacking away at the ocean with a sword— courageous perhaps, but ultimately useless. A synecdoche—“that flesh (meaning humanity) is heir to”—suggests the supremacy of the physical body, and the word choice of “consummation” to mean a result hints at carnality as a source of Hamlet’s vulnerability. Of course, the almost hackneyed metaphor of death as a sleep in this passage takes on new meaning as Hamlet contemplates the dreams that would inevitably pertain to that particular form of sleep. Even the rather odd expression—“shuffled off this mortal coil”—suggests the transformation of a coiled snake as it sheds its old skin, a figure of speech that might possibly indicate the hope of a new life. The “whips and scorns” of time, however, are life’s sufferings, while the image of a traveler bearing “fardels” depicts the weighty and burdensome nature of existence. Another extended metaphor of death as “the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns” serves as a means of conveying Hamlet’s fascination with and fear of the unknown. In addition, the personification of resolution as a patient whose complexion has become sick and pale makes a mockery of ideals of valor and heroism. The hero who might have taken up arms against a sea of troubles at the beginning of the soliloquy might find his ambition dissipated as the very “currents turn awry.” While each instance of figurative language in the passage is effective and expressive in its own right, it is the rich and contradictory conglomeration of metaphors pouring forth from Hamlet’s imagination that truly reveals the depth of his mental anguish. Style and punctuation, logical structure, and figurative language—all bespeak Hamlet’s agony as he readies himself for his sworn revenge. The violent action which his revenge will of necessity call forth, however, is in sharp contrast to the watchful, perceptive, careful planner that Hamlet is—the actor who may very well know that Claudius and Polonius are watching him and hearing every word. Do the soliloquy’s inherent contradictions reveal its speaker’s insanity? Or do they rather indicate the subtly probing, sensitively questioning, and spiritually honorable character of Hamlet? Generations have chosen the latter explanation, committing to memory these lines that so exquisitely capture the doubt, fear, trembling and wondering about our existence that lies at the heart of each of our souls, no matter who we might be . . . or not be.