HPS 0437 – Darwinism and its Critics

advertisement

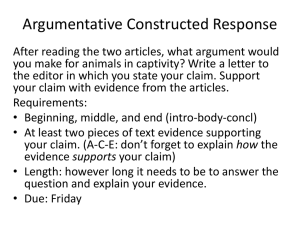

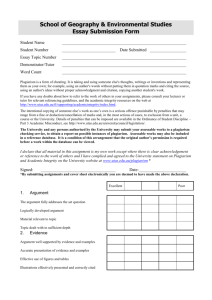

PHIL 4607 –Spring 2007 PHIL 4607 – Philosophy of the Biological Sciences (Spring 2007) Revised and Developed Response (Final) Paper Specifications The final paper requires you to take one of your earlier response papers and develop it more fully (which may mean giving up most of what you previously wrote). The goal of this assignment is to gather together your own initial reactions captured in the exploratory writing and use them (including your guided journal) along with class conversations to augment and sharpen your discussion of an idea or argument. It is not a research paper (in the sense of doing extensive library research on a topic), but finding connections among class readings will be a natural strategy during your writing. (This is advanced formal writing, which emphasizes the revision of writing and restructuring of arguments to increase clarity and probative force.) Your paper should include a reconstruction of the arguments for a particular philosophical issue, necessary background for understanding the issues and related argument, the evidence adduced for the argument, criticisms of the argumentative strategy or its elements, and an articulation of outstanding questions. Your paper should have the following structure: 1. Introduction: Carefully state the crux of the philosophical issue, the paper/chapter/reading that it arises in, and outline the main elements of your paper [~1-2 paragraphs]. 2. Background: Contextualize the philosophical issue from the paper/chapter/reading with some appropriate historical and philosophical commentary [~1 page]. 3. Argument Reconstruction: What is the main argument of the author under scrutiny (with respect to the philosophical issue in view)? Why is it interesting? How would you reconstruct the argument? [~1-2 pages]. 4. Argument Evaluation: Is the argument well structured (or valid)? Are there any ambiguous steps in the argument? Should the premises be accepted? Are there good reasons for accepting them? What else follows from the argument, especially for philosophical or scientific issues not discussed by the author? Are there any unstated assumptions lurking in the argument? [~2-3 pages] 5. Countenance Possible Responses: How might the author deal with the concerns and criticisms you raise? Can they be dealt with or do they undercut the conclusion the author wants to reach? [~1 page]. 6. Overall Merit of Argument: On the basis of (4) and (5), make an overall evaluation of the paper/chapter with respect to the argument you are scrutinizing [~1-2 paragraphs]. 7. Outstanding Questions/Emerging Issues: You cannot address everything in your paper. What questions emerge from your discussion? Where might you go next with another paper? [~1-2 paragraphs] 8. Conclusion: Summarize your argument succinctly, highlighting the main structure of your paper. No new information should be introduced in the conclusion. [~1-2 paragraphs] Page numbers guidelines are for your planning purposes but are not rigid (i.e. 3 paragraphs on the overall merit of the argument will not cost you, although 5 pages of background will). It would be a very good idea to review the excerpts from “The London Philosophy Study Guide”, handed out with this instruction sheet. The section “Writing Philosophy” is highly relevant; make sure you read it. (The sections on citations/references and plagiarism are similar to those reproduced below in this document.) 1 PHIL 4607 –Spring 2007 Why are we doing this paper assignment? The main reason for writing this paper is that it gives you the opportunity to do a detailed discussion of ideas and arguments we have been reading and allows you to critically discuss the merits or drawbacks of various theses put forward in our discussions. This helps me to evaluate your learning and comprehension in the course. Papers are the main forum for the presentation of ideas in the university and our culture more broadly. Whether you are a biology, business, philosophy, or literature major, the paper format is the accepted medium for the exchange of ideas among peer researchers. More specifically, this paper assignment is training for you in writing a research paper in the discipline of philosophy (and philosophy of science more particularly). What does this paper assignment consist in? The final paper is supposed to be ~8 pages long (12 pt., double-spaced, ~2,000 words). It may help to think of your paper as a critical discussion, in essay form, whereby ideas are exchanged and evaluated in a civil fashion. This means that you need not have an entirely new idea to write a good paper. A well-composed paper must frame the question under investigation, examine relevant information, and evaluate answers to the question as well as assumptions that lie behind it, weighing their advantages and disadvantages. (See above on paper structure and below on “Elements of a Good Paper”.) Who is the audience of the paper? Knowing the audience you are writing for is important since it shapes the style of your paper. You should write your paper for a fellow university student who may have little to no familiarity with the material. Thus you cannot assume they are aware of the issues and topics covered in class. Do not write your paper for me (the instructor); i.e. do not assume your reader has a relatively good grasp of everything we have discussed in class. A good test of whether or not you are successful is to have a peer read your paper. If they can follow it and comprehend your argumentative strategy, this is positive sign that you have achieved your goal. When are the due dates? The final paper is due by 5/6 at midnight. Late papers are not accepted. I expect all papers to be submitted electronically even if a paper copy is handed in earlier. Acceptable file formats include: .doc, .rtf, .pdf, and .txt (ask if you have questions about these). How can I make sure I get a good grade? The best answer to this question is ‘follow the instructions.’ Everything you need to know is in this handout or on the syllabus. You should consult both from time to time to check your progress. Do not hesitate to ask any questions you might have. 2 PHIL 4607 –Spring 2007 Elements of a Good Paper Students often complain that papers are graded “subjectively”. Although there is some truth in this complaint, a paper can also be graded against an objective standard. The following is a brief description of expectations concerning this paper assignment. You should consult them before and after you write your paper. Even though I do not ‘mark off’ for spelling and grammar mistakes, they can have an effect on my reading of your paper if they are pervasive. Two ways to avoid this are to use a spell checker and have someone else read your paper. Outline of a paper (for any written assignment) Introduction: Set up the problem/question. What is at stake? Who are the main players? Have you set the stage with dates and places (context)? What texts will you examine? What is your thesis? Does your opening catch the reader’s attention? Summary: Tell me what you are going to say. Body: Wade into the messy details…this is where you bring forward the specifics of theories or unpack the problem with reference to particular texts. This is where your thesis gets “bite”. Here it is important to relate evidence positive and negative for different positions and issues. (Balance your presentation.) Utilize two or three selectively chosen examples, if possible. Summary: Tell me what you want to say. Conclusion: Summarize your paper…indicate your findings and any key results derived. Point out the significance of your thesis by referring to your strategies used in the body of the paper. If relevant, suggest areas of future research or indicate unanswered questions or problematic areas that still remain in your covered topic or question. Summary: Tell me what you said and why it’s important *Although you do not need to make special ‘sections’ that correspond to the eight different items you must include in your paper structure, these are the elements I will be looking for while I grade (see Final Paper Point Breakdown on last page of this handout). Refer back to this handout before you turn in your final draft. 3 PHIL 4607 –Spring 2007 Grading Rubric (general) A (30-35 pts.): Answers question and/or discusses issue with skill. Very few, if any, flaws in the argumentative structure. Adheres to various guidelines indicated in assignment handout. (Focused, organized, and well developed.) B (24-29 pts.): Answers question and/or discusses issue well. Some flaws in argumentative structure and problematic evidential support. Adheres to various guidelines indicated in assignment handout. (Mostly focused, organized, and developed.) C (18-23 pts.): Answers question and/or discusses issue somewhat adequately. Major flaws in argumentative structure and/or problematic or absent evidential support. Deviates somewhat from guidelines indicated in the assignment handout. (Somewhat focused, lacks organization and/or development.) D (12-17 pts.): Answers question and/or discusses issue inadequately/poorly. Argumentative structure is hard to discern, possibly absent. Deviates from guidelines indicated in the assignment handout. (Lacks focus, organization, and development.) F (11 pts. or below): Clearly fails to fulfill the above conditions set forward in all or most respects. +/- grades can be used to reflect the point gradations in the above grading rubric. They allow for a more nuanced grading of the papers that attends to their various merits or faults more specifically. But only your point score will be entered into the grade book. Helpful Reminders - No cover sheet is necessary; name, date, etc. can be located in the upper left or right of your first page. Please staple your paper together rather than using a paper clip if submitting a hard copy. - Do not use contractions in your writing (e.g. isn’t, don’t, or didn’t). - Be careful in your use of pronouns; it should be unambiguous in context (e.g. who does “he” refer to?). - Plagiarism is a serious offense and could be grounds for discipline by the university. Consult this sheet and the citation criteria page (below). If after doing so you are still unsure, please come talk to me so I can clarify your unanswered questions. 4 PHIL 4607 –Spring 2007 Citation Criteria Give credit to your sources by referencing all your sources. If you are giving the exact words of a particular author then you should indicate it by placing those words in quotation marks. If you are taking ideas only, but not exact words, you still have to give the reader a reference to locate those ideas. Use quotes when you are interested in showing an author’s exact use of words. If you are not interested in this, and the expression breaks the rhythm of your paper, you can adapt them to your narrative and style (but you still need to give the author credit for the idea.) Citation Examples* Footnotes - Books 1. Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An interpretation, 2 vols. (New York: A. Knopf, 1966-69), 2: 319. -Articles 1. A. Sutton, “The Analysis of Free Verse Form, Illustrated by a Reading of Whitman,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 18 (December 1959): 241-54. Author-Date Text Citation A) First, in the main text you write: (Blinksworth 1987, 125) (Sober 1984, 222) B) Later, in the reference list: Blinksworth, Roger. (1987) Converging on the Evanescent. San Francisco: Threshold Publications. Sober, Elliot. (1984) The Nature of Selection. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. * Please see me in advance if you have any questions. You may also consult The Chicago Manual of Style: 14th edition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1993).1 See also: http://www.lib.umn.edu/undergrad/ . Plagiarism Plagiarism means submitting work as your own that is someone else’s. For example, copying material from a book or other source without acknowledging that the works or ideas are someone else’s and not your own is plagiarism. If you copy an author’s words exactly, treat the passage as a direct quotation and supply the appropriate citation. If you use someone else’s ideas, even if you paraphrase the wording, appropriate credit should be given. You have committed plagiarism if you purchase a term paper or submit a paper as your own that you did not write.2 Ideas or quotations from lectures, recitations, your textbook or any other source must be cited. Even when the citation is included in the text (for example: “In last week’s lecture, Professor Trinity noted that the Spanish American war disrupted American foreign policy.”), it is strongly recommended that you provide a full citation in a footnote or endnote (See Citation Examples above, and Plagiarism Examples below.) Books with guidance on citation are available at Wilson library here at the U. Ask at the reference desk for assistance. See also: http://www.lib.umn.edu/undergrad/ . See also: MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers or Kate Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. 2 B. G. Davis, Tools for Teaching (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993), 300. 1 5 PHIL 4607 –Spring 2007 EXAMPLES In the three examples below the passage that follows is used to illustrate typical forms of plagiarism. The passage is from page 891 of the textbook, America’s History. Many of these new workers in the service economy were women: twice as many women were at work in 1960 as in 1940. Because of the structural needs of the economy, there was a demand for workers in fields traditionally filled by women, such as clerical work, a predominantly female field that expanded as rapidly as any other whitecollar sector in the economy. Teachers to staff the nation’s burgeoning school systems were also in demand. Growing sectors of the economy such as restaurant and hotel work, hospitals, and beauty care offered low-paying jobs to women, jobs that have been called the “pink-collar ghetto.” Example #1: Copying Selected Sentences or Parts of Sentences is Plagiarism New service workers were often women: twice as many women were at work in 1960 as in 1940. Clerical work expanded as rapidly as any other white-collar sector in the economy. Teachers to staff the nation’s burgeoning school systems were in demand. Also restaurant and hotel work, hospitals, and beauty care offered low-paying jobs to women, jobs that have been called the “pink-collar ghetto.” Example #2: Paraphrasing is Plagiarism A large number of the new employees in service jobs were female: two times as many females were employed in 1960 as in 1940. Because of the needs of the economy, there was a greater demand for women in traditional fields. New jobs included clerical work, a primarily female employment that expanded as quickly as any other white-collar portion of the economy. Teachers to man the nation’s swelling school districts were also in short supply. Growing portions of the economy such as restaurant and motel work, health care facilities, and beauty parlors offered menial jobs to women, jobs that have been referred to as the “pink-collar ghetto.” Example #3: Using Others’ Ideas without Giving Credit to the Author is Plagiarism Following World War II, women worked in increasing numbers outside the home. However, more women at work did not translate into job market equality. Women were trapped in the “pink-collar ghetto,” the giant service sector of the rapidly growing post-war economy. From 1940 to 1960, the number of women working in the service industry doubled. The luckiest worked as teachers or secretaries, but the majority of the nation’s African American and working-class women were forced to seek employment in low paying but “[g]rowing sectors of the economy such as restaurant and hotel work, hospitals, and beauty care.” An Example of the Proper use of Sources and Citations Following World War II, women worked in increasing numbers outside the home. However, more women at work did not translate into job market equality. Women were trapped in the “pink-collar ghetto,”3 the giant service sector of the rapidly growing post-war economy. From 1940 to 1960, the number of women working in the service industry doubled.4 The luckiest worked as teachers or secretaries, but the majority of the nation’s African American and working-class women were forced to seek employment in low-paying but “[g]rowing sectors of the economy such as restaurant and hotel work, hospitals, and beauty care.” 5 3 James Henretta, W. Elliot Brownlee, David Brody and Susan Ware, America’s History. (New York: Worth Publishers, 1993), 891. 4 Henretta, 891. 5 Henretta, 891. 6 PHIL 4607 –Spring 2007 Final Paper Point Breakdown PHIL 4607 – Philosophy of the Biological Sciences (Spring 2007) Name: Actual Possible Introduction 3 Background 4 Argument Reconstruction 6 Argument Evaluation 8 Countenance Possible Responses 4 Overall Merit of Argument 4 Outstanding Questions/Emerging Issues 3 Conclusion 3 x 35 Comments: * Notice that the two sections that count for the most points are ‘Argument Reconstruction’ and ‘Argument Evaluation’. 7