REALITY-OF-CONSENT

advertisement

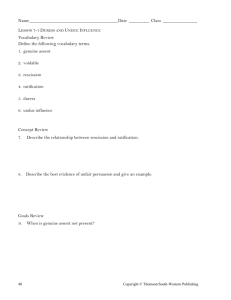

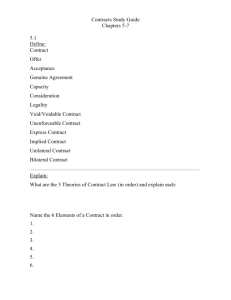

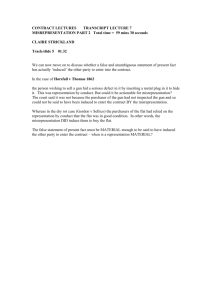

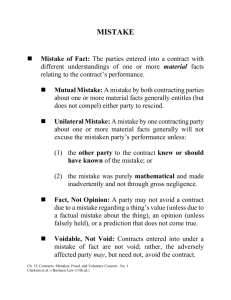

REALITY OF CONSENT MISREPRESENTATION, MISTAKE, AND MIND CONTROL INTRODUCTION Generally, for a contract to be valid, it must represent the mutual agreement of parties who are aware of the facts relating to the contract and are exercising their own free will in deciding to become legally bound. This chapter examines those contracts which have the appearance of being such a mutual agreement, but in reality are not because the consent of one or both of the parties is based on either a misunderstanding of the facts or the exercise of someone else's will. For a "catchy" subtitle, I have chosen: Misrepresentation, Mistake, and Mind Control. In addition to the fact that I like alliteration, these three words accurately sum up the several traditional theories in this area as follows: "misrepresentation" represents the legal concepts of Fraud and Innocent Misrepresentation; "mistake", the concepts of Mutual Mistakes and Unilateral Mistakes; and "mind control" reflects the concepts of Duress and Undue Influence. Each of these legal concepts will be examined below. AGREEMENTS BASED ON MISREPRESENTATIONS INTRODUCTION Sometimes the agreement of one party to enter a contract is based on representations of fact made by the other party. If the representations are false, the apparent agreement of the parties is not real because there would not have been any agreement if the true facts had been known. When the misrepresentation is made under circumstances where the party making the misrepresentation knew or should have known that it was false, the legal concept of Fraud comes into play; if the mis- representation is made without either actual or constructive knowledge, than the concept of 1 Innocent Misrepresentation applies. FRAUD Fraud In The Execution Fraud in the execution involves a misrepresentation as to the nature of the agreement; one party does not know he is entering into a contract. Where there has been fraud in the execution the "contract" is absolutely void. For example, if Robert Redford were signing autographs in a crowd outside the opening of his new movie and someone, while covering the remainder of a form contract, presented Redford with the contract which he then signed, the "contract" would be absolutely void on the basis of fraud in the execution. Fraud In The Inducement Fraud in the inducement takes place when one party enters into a contract because his agreement is induced by a material misrepresentation of fact made by the other party. The defrauded party knows that he is entering a contract, but the facts which motivated him to enter the agreement are not what the other party represented them to be. In their shortest form the elements of fraud in the inducement are: (1) a misrepresentation of fact; (2) knowingly made; (3) with the intention to deceive; (4) which is justifiably relied upon; (5) and causes injury. These five elements represent a condensed version of the following more complex ideas: 1. A material misrepresentation of a past or present fact made actively or through concealment; 2. Made with the knowledge that it is false, or under circumstances where the party making the misrepresentation either should have known of the falsity or had no basis upon which to assert the fact as true; 3. Made with the intention that it be relied upon by the other party; 4. That the other party, while exercising reasonable diligence for his own protection, justifiably relied upon the representation; and, 2 5. That the reliance upon the misrepresentation led to some injury. Cases 1A-1D: Dwarg Farquart was in the market for a new house, so one day while he was out for a drive he saw a "House for Sale" sign and went in to investigate. The owner, Glenda Glibb, told him the following about the property: (a) that the house was in fine condition; (b) that she had purchased the property five years earlier for $60,000 and that it was now worth $100,000; (c) and that the house was situated on a 1 1/2 acre lot. Dwarg really liked the house and ended up purchasing it for $86,000. After he moved in, Dwarg discovered the following: (a) that the plumbing and wiring were in need of extensive repair; (b) that the market value of the house was approximately $82,000; (c) that the lot was only 1.496 acres; and (d) that the house was termite infested and boards had been put up to hide the infestation. Dwarg brings suit against Glenda for fraud on the basis of Glenda's statements and the termite infestation. The probable results would be as follows: 1A. "fine house": Dwarg would lose because this is a statement of opinion rather than a statement of fact. Such opinion descriptions when used in sales transactions are called "puffing". To be actionable, Glenda would have had to make a factual statement such as: "The wiring in the house is not in need of repair." 1B. "value $100,000": Dwarg would also lose on this statement because statements of value are generally regarded as opinions or statements of future possibility rather than present fact. Note: A statement of value or capacity may be treated as a present statement of fact when given by an expert. Two examples are: (1) where a jeweler gives a statement of the market value of a diamond; or (2) where a furnace salesman represents that a particular model can heat a particular house to 70 degrees when the outside temperature is 20 below. 1C. "1 1/2 acres": Dwarg would lose because the difference in area would not be a material part of the bargain. 1D. The termite infestation: Dwarg would win even though Glenda did not make a representation concerning termite infestation. This would be fraud by concealment, assuming, of course, that Glenda was responsible for the boards hiding the infestation. Note: Generally, there is no duty to speak when entering a contract, however such a duty could arise and become the basis for fraud under the following circumstances: (1) where there is a fiduciary or confidential relationship between the parties; (2) where there is a defect known to the seller and not readily discoverable by the buyer; or (3) where a party makes an innocent misrepresentation during negotiations and later learns of its falsity but does not inform the other party prior to the finalization of the 3 contract. For the "knowingly made" requirement of fraud to be met the party making the representation is liable for fraud even if he didn't actually know the representation to be false, provided the circumstances are such that he either should have known it was false or made the representation without any basis upon which he could know it was true or false. Case 2A: Our friend Dwarg, having learned a lesson with Glenda, asked very specific questions when buying a used car at Honest Abe's Auto Sales. He asked if the brakes needed relining, and Abe responded: "No". Needless to say, after he purchased the car, he learned that the brakes did in fact need relining and sued Abe for fraud. Abe defended on the basis that he had received the car sold to Dwarg the morning of the sale as a trade-in, that he never examined the brakes, and that he, therefore, could not have known his misrepresentation to be false. Dwarg would win because the court would hold Abe responsible for his representation as Abe had no basis upon which to know whether it was true or false. This rule could be subtitled: "If you don't know, either say you don't know or keep your mouth shut." Case 2B: Assume the same facts as in 2A except that Dwarg purchased the car from the owner who had the car for three years. The court would hold the owner responsible whether he actually knew the brakes needed relining or not because, as the owner of the car for three years, he should have known the misrepresentation to be false. Again, "I don't know" or "I haven't had a problem with the brakes" would have been viable alternative replies by the owner. The "intent to deceive" requirement is met if the person to whom the representation is made is the person who enters the contract. If a misrepresentation made to Smith is overheard by Jones, who then enters into a contract with the person making the misrepresentation, Jones could not recover for fraud because he was not the person to whom the misrepresentation was made. The "justifiable reliance" requirement can be subtitled: "If you're a jerk, you lose". Since the negotiation of a contract is adversarial in nature, people negotiating 4 contracts are required to act reasonably to protect their own interests and not merely take the other party's representations as "gospel". How much reliance will be justifiable depends on all the circumstances of the case, there is no hard and fast rule. Some guidelines, however, are as follows: (1) how obvious the truth is; (2) the cost of discovering the truth in relation to the cost of the entire contract; and (3) the experience of the party relying upon the misrepresentation in similar matters. Case 3: Dwarg, interested in making an investment, enters negotiations for the purchase of an orange grove. He asks the seller, Anita Hydrant, whether there has been any frost in the last five years that caused damage to the orange crop, to which Anita replies: "No". He discovers that in three of the last five years there had been frost which damaged the orange groves and sues Anita for fraud. Dwarg would lose because his reliance on Anita's representation was unjustified considering he could have found out the truth by making a call to the weather bureau--a cost of 25 cents to protect an investment of $150,000. Note: Students often have a problem with "justifiable reliance" in that it can result in someone who has unquestionably made a false representation not being liable for fraud. There must be some injury, a loss, to the party relying on the misrepresentation for fraud to apply. Where the misrepresentation actually turns out to benefit the party relying upon it, a case for fraud can not be maintained. For example, if a party purchases a stone misrepresented to be a ruby which turns out to be a diamond more valuable than the ruby would have been, a suit for fraud would be inappropriate. If, however, a party purchases land on the basis of a misrepresentation that there are copper deposits on the land, and while looking for the copper the party finds oil, a suit for fraud would sill be possible because the land can have more than one quality--both copper and oil-- whereas the stone can either be a ruby or something else other than a ruby. Remedies For Fraud in the Inducement 5 It must be noted that fraud is both a contract concept and a tort concept under the title "fraud and deceit" which has essentially the same elements as fraud under contract theory. This being so, the available remedies for fraud are more numerous than in purely contractual situations. The remedies for fraud are either rescission or compensatory damages, and if fraud and deceit can be established, then punitive damages may be available in addition to compensatory damages. Rescission would result in setting aside the contract and returning the parties to the positions they were in prior to the contract being made. Compensatory damages would compensate the defrauded party by allowing him to recover the monetary difference between the value of the subject matter of the contract if it had been as promised and the value of it as received. Punitive damages available under fraud and deceit in tort would provide a further amount of money to the defrauded party as punishment to the wrongdoer. Case 4: After the fiasco with Glenda, Dwarg was in the market for a house again. He found a house he really liked on a large, wooded lot with a babbling brook babbling by the house. As the brook was near the house, Dwarg asked the seller, Slim Slimy, if there had ever been any problem with water going down the basement when the spring thaws caused the water in the brook to rise. Even though Slim knew that water had gone down the basement when the previous owner had owned the house, he responded to Dwarg's inquiry as follows: "I've never had a problem with it." After the first spring thaw, Dwarg discovered that he had an unexpected indoor swimming pool and sued Slim for fraud. Dwarg would win his suit for fraud because Slim's half-truth, under these circumstances, would be fraudulent. If Dwarg sought rescission as a remedy, he would give the house back to Slim and Slim would give him the purchase price back. Compensatory damages would take the form of Slim paying Dwarg the difference in value between the property with and without the problem with the babbling brook babbling down the basement. Under fraud and deceit in tort, Dwarg could be awarded an amount of money in excess of his compensatory damages to punish Slim for his wrongful act. INNOCENT MISREPRESENTATION There are two basic differences between fraud and an innocent misrepresentation: 6 first, element 2 of fraud is missing--the misrepresentation is made innocently rather than knowingly; and second, the only remedy for innocent misrepresentation is rescission. Rescission is available on the theory that the party making the misrepresentation, however innocent, is not entitled to the benefits of the contract if the other party wishes to have it set aside. The lack of damages as a remedy for innocent misrepresentation can result in the elimination of any practical remedy. Case 5: Assume the same facts as in Case 4 except that Slim did not know that the previous owner had problems with the babbling brook (the previous owner misrepresented this fact to Slim), and that Slim's response to Dwarg was definite: "The water has never gone down the basement". In those circumstances, if the value of the property has increased and/or Dwarg does not want to part with the property, then Dwarg will have no practical remedy for Slim's innocent misrepresentation, an action for damages being unavailable. AGREEMENTS BASED ON MISTAKES MUTUAL MISTAKES If both parties to an agreement are mistaken about an essential part of the bargain, such as the existence or identity of the subject matter, the attempted contract may be rescinded. Actually, in such circumstances a contract never comes into existence because there is no real meeting of the minds. A famous, old case in this area had to deal with the sale of cotton to be shipped to the buyer on the ship "Peerless. Neither party was aware that there were two ships named Peerless and each party had a different ship in mind: the buyer, the ship that sailed earlier; the seller, the later ship. The court held that no contract resulted. There would have been the same result if the parties had been mistaken about the existence of the subject matter, say, for example, if a single Peerless had sunk prior to the making of the contract unbeknownst to either party. A mutual mistake as to the nature of the subject matter of the contract will not result in relief when the parties assume the risk that the subject matter may not be what 7 they believe it to be. For example, if a purchaser buys a painting on the belief that it may be an original by a famous artist, and the seller sells the painting without representing it to be an original, neither party can rescind whether the painting turns out to be very valuable or worthless. If, however, both parties assume the subject matter to be something which it turns out not to be, rescission is available. For example, if in the contract for the sale of the painting both parties assumed the painting to be an original, then the contract could be rescinded if the painting turns out to be a copy. It is interesting to note the relationship between mutual mistakes and innocent misrepresentations: all innocent misrepresentations will result in mutual mistakes, however, only some mutual mistakes will be the result of an innocent misrepresentation. In Case 5, when Slim made is innocent misrepresentation about the babbling brook, he was mistaken about the facts. When Dwarg believed Slim, he became mistaken about the babbling brook, therefore, there was both an innocent misrepresentation and a mutual mistake of fact. The Peerless case involved a mutual mistake without any innocent misrepresentation. This relationship will allow you to attack an innocent misrepresentation problem using either innocent misrepresentation theory or mutual mistake theory. See the figure below: UNILATERAL MISTAKES Generally, the court will not allow a remedy for a unilateral mistake--if only one party is mistaken, too bad for that party. Some examples of unilateral mistakes for which a court would not grant relief are: mistakes as to the value of the subject matter (you have the right to make a bad deal); mistakes due to the failure to read the contract; and 8 mistakes as to the legal meaning of the contract. There is one exception to this rule where the court will allow equitable rescission of a contract involving a unilateral mistake. This exception consists of the following four elements: (1) One party is mistaken; (2) The other party knows or should have known of the mistake; (3) It would be unjust to allow the non-mistaken party to take advantage of the mistake; and, (4) The parties can be returned to the status quo—they can be put back where they started. Where these elements are present, the court will grant relief. Many of the cases in this area deal with mistaken bids on construction contracts where there has been an arithmetical error or an item has been left out of the bid. In such a case, the court would rule that it would be unconscionable to allow the non-mistaken party to "snap up" the bid and would permit rescission. CONTRACTS BASED ON MIND CONTROL DURESS When a party has entered into a contract, not as an exercise of free will but as a result of fear induced by the wrongful threats of the other party, the contract may be rescinded on the basis of duress. The standard in duress cases is not whether a reasonable person would be put in fear by the threats, but whether the party claiming duress was, in fact, deprived of a free will choice through fear. At common law, for threats or acts to constitute duress, they had to consist of either criminal or tortious conduct. For example, threats of physical violence would, at common law, ordinarily be sufficient to establish duress. Today, a wrongful act or threat can provide the basis for duress without being a tort or a crime. If there has been a wrongful act, and if that act has the effect of preventing a party from making a free choice, the courts will generally 9 grant relief. Case 6: Dwarg was at one time employed by Continental Wazoo Corporation. His employment was at the will of his employer. Through a stock option program, Dwarg and his fellow employees had purchased a substantial minority interest in Continental. Continental, intending to merge with another company, informed Dwarg and the other employees that it wished to purchase their stock, and that the failure to sell would be regarded as an act of disloyalty to the corporation. Dwarg, fearing that he would be fired if he did not sell the stock to the corporation, entered into a contract to transfer the stock. Two months later, after he had obtained employment elsewhere, Dwarg brought suit to have the stock sale set aside on the basis of duress. Even though at common law there would be no duress because the corporation would have the right to fire Dwarg at any time, it is not unlikely that a court would allow rescission on the basis that the corporation's threat was wrongful and had coerced Dwarg through fear into selling the stock. UNDUE INFLUENCE With duress a party is coerced to enter a contract through fear; with undue influence a party is coerced by way of misplaced trust in the other party. Generally, undue influence applies in situations where there is a confidential or fiduciary relationship, and the person in the superior position uses that position of confidence to take advantage of the other party. Confidential or fiduciary relationships include such relationships as: parent--child; guardian--ward; husband--wife; doctor--patient; attorney--client; minister--parishioner; and, perhaps, other close family relationships. If there is a confidential or fiduciary relationship and there a contract made which benefits the party in the superior position to the detriment of the party in the inferior position, undue influence will be presumed. Such a presumption will require the party in the superior position to come forward with evidence to show that the party in the inferior position entered the contract of his own free will. Case 7: Our dear friend Dwarg has fallen upon bad times. He has had a stroke, and although he still retains his faculties, he has become increasingly dependent on his "spinster" daughter Dwargette. 10 Dwargette tells her father that as another stroke might kill him, he should arrange his affairs as soon as possible. She says that if he transfers all of his property to her now, she will make sure the rest of her brothers and sisters are taken care of without the necessity of expensive probate proceedings. She makes arrangements to have a contract drawn up with her consideration being $1.00 and has witnesses come to attest to the signing. If Dwarg decides to have the contract set aside on the grounds of undue influence, Dwargette will have the burden of offering evidence to show that Dwarg entered the contract of his own free will. 11