to Word document - Southern Connecticut State University

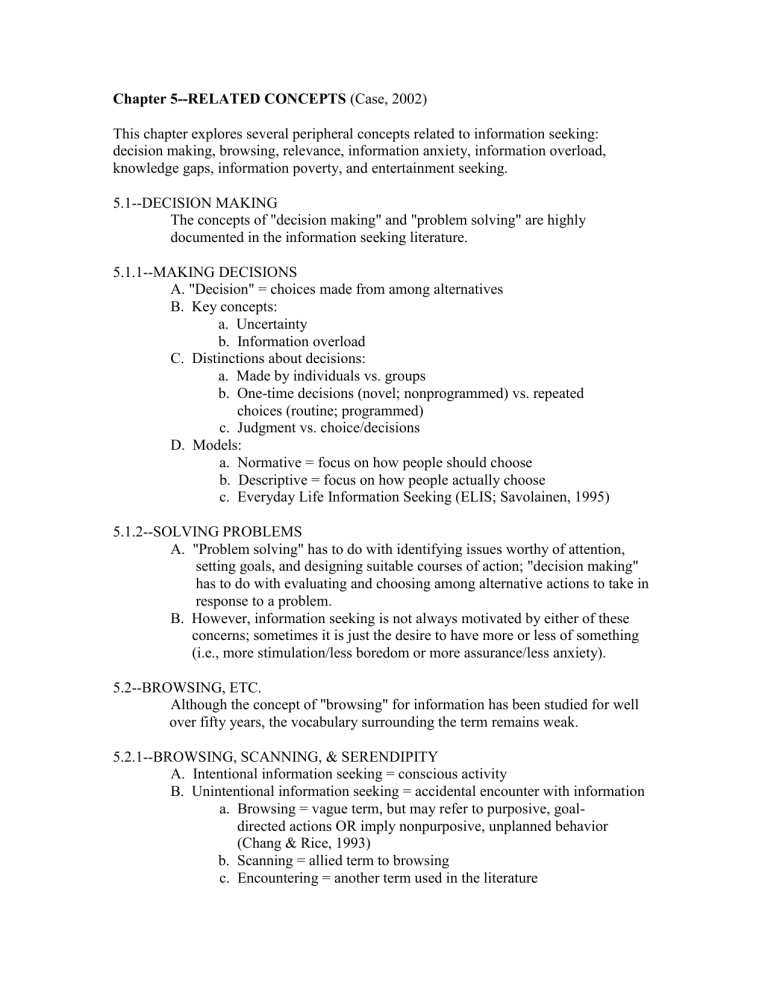

Chapter 5--RELATED CONCEPTS (Case, 2002)

This chapter explores several peripheral concepts related to information seeking: decision making, browsing, relevance, information anxiety, information overload, knowledge gaps, information poverty, and entertainment seeking.

5.1--DECISION MAKING

The concepts of "decision making" and "problem solving" are highly documented in the information seeking literature.

5.1.1--MAKING DECISIONS

A. "Decision" = choices made from among alternatives

B. Key concepts:

a. Uncertainty

b. Information overload

C. Distinctions about decisions:

a. Made by individuals vs. groups

b. One-time decisions (novel; nonprogrammed) vs. repeated

choices (routine; programmed)

c. Judgment vs. choice/decisions

D. Models:

a. Normative = focus on how people should choose

b. Descriptive = focus on how people actually choose

c. Everyday Life Information Seeking (ELIS; Savolainen, 1995)

5.1.2--SOLVING PROBLEMS

A. "Problem solving" has to do with identifying issues worthy of attention,

setting goals, and designing suitable courses of action; "decision making"

has to do with evaluating and choosing among alternative actions to take in

response to a problem.

B. However, information seeking is not always motivated by either of these

concerns; sometimes it is just the desire to have more or less of something

(i.e., more stimulation/less boredom or more assurance/less anxiety).

5.2--BROWSING, ETC.

Although the concept of "browsing" for information has been studied for well

over fifty years, the vocabulary surrounding the term remains weak.

5.2.1--BROWSING, SCANNING, & SERENDIPITY

A. Intentional information seeking = conscious activity

B. Unintentional information seeking = accidental encounter with information

a. Browsing = vague term, but may refer to purposive, goal-

directed actions OR imply nonpurposive, unplanned behavior

(Chang & Rice, 1993)

b. Scanning = allied term to browsing

c. Encountering = another term used in the literature

d. Serendipity = special case of browsing used to distinguish the

accidental discovery of information (Apted, 1971)

C. Related concepts

a. Information absorption may be unintentional.

b. Motivations for information seeking are not necessarily always

tied to specific goals but may instead be based purely on curiosity

(Toms, 1999).

5.2.2--ADDITIONAL DISTINCTIONS

A proliferation of terminology has been developed to describe varying

degrees of browsing. Examples (Chang & Rice, 1993) of these distinctions

include:

A. Well-defined (formal search & retrieval)

E.g., seeking a particular book on a specific subject

B. Semidefined (browse, forage, scan)

E.g., finding books on a general subject

C. Poorly defined (browse, graze, navigate, scan)

E.g., finding any material on a subject of potential interest

D. Undefined (encounter, serendipity)

E.g., discover new, unanticipated items of interest

5.3--RELEVANCE, PERTINENCE, & SALIENCE

The choice of sources that are attended to and the meanings that are derived are highly dependent on context. "Context" in this scenario includes the information seeker's situation, background, and environment, all of which influence perceptions during the information seeking process.

5.3.1--RELEVANCE & PERTINENCE

Definitions of Relevance

A. Having a close, logical relationship to a matter, topic, thought, remark, or

question

B. The interpretive connection that is made between observed patterns and

the context of the observation (Ritchie, 1991)

C. A key aspect of efficiency in human information processing; equated

with "aboutness" and "topicality" (Sperber & Wilson, 1995)

5.3.2--RELEVANCE IN INFORMATION RETRIEVAL

A. Objective measures of relevance include defining relevance as being based

on the relationship between an information request and the content of a

collection of document records (Belkin & Vickery, 1985).

B. However, this definition does not take into account the contextual nature

of human judgment.

C. Thus, a newer, subjective view defines relevance as being based on the

knowledge state and intentions of the user (Mizzaro, 1998); may be referred

to as situational or psychological relevance or pertinence

D. The subjective view of relevance argues for the importance of the user's

knowledge state and intentions at the time of encountering information.

5.3.3--SALIENCE

A. A "salient" item stands out from the background and is perhaps more

easily recalled later.

B. Salient items are not necessarily relevant to a current information need.

C. Potentially relevant information sources may not appear salient at the time

an information need begins to emerge.

5.4--AVOIDING INFORMATION

The phenomenon known as "selective exposure" deals with the decision NOT

to pay attention to information.

5.4.1--SELECTIVE EXPOSURE & INFORMATION AVOIDANCE

A. People interested in a topic tend to acquire more information about it

(Chew & Palmer, 1994; Reagan, 1996).

B. In general, people seek information that supports their prior beliefs,

opinions, and knowledge and avoid conflicting information.

C. However, there are instances when people welcome contradictory

statements (Sears & Freedman, 1967).

D. Failure to act on information is due less to selective exposure and more to

a rejection or avoidance of that information (Sears & Freedman, 1967).

E. Filtering or nonuse behavior describes a conscious decision to reject

potentially relevant materials (Wilson, 1995).

F. Thus information may be avoided but is more often simply not used.

5.4.2--KNOWLEDGE GAPS & INFORMATION POVERTY

A. "Knowledge gap" = when, for any number of reasons, entire groups of

people do not get the same information as other people

B. "Information poverty" = the state of what seems to be permanent

ignorance in some segments of a population

C. Those that are information savvy tend to remain so and/or improve,

whereas those that are information poor tend to experience many "barriers to

knowledge acquisition" (Dervin, 1989; Gaziano, 1997). This discrepancy

appears to be linked to socioeconomic status.

5.4.3--INFORMATION OVERLOAD & ANXIETY

A. In contrast to a state of ignorance about something, it is also possible to

have too much information.

B. "Information overload" = the state of an individual or system in which

excessive communication inputs cannot be processed, leading to breakdown

(Rogers, 1986).

C. This section of chapter 5 summarizes a plethora of research on the topic of

information overload.

D. Seven categories of responses to overload (Miller, Galanter, & Pribram,

1960): omission, error, queuing, filtering, approximation, multiple

channels, & escaping. These strategies are employed "at our peril."

E. Anxiety may be reduced by seeking knowledge as well as by avoiding

knowledge (Maslow, 1963).

5.5--INFORMATION VERSUS ENTERTAINMENT

A. The study of information seeking has tended to reinforce an artificial

distinction between "entertainment" and "information" based on the

presumptive "less serious" nature of entertainment (Zillman & Bryant,

1986).

B. This section of chapter 5 describes the work of a number of investigators

on the intermingling of entertainment and information in print and electronic

formats.

C. The desire to be entertained greatly influences the sources to which people

turn when seeking information.

QUESTION 1:

Rather than turning to the most rational or authoritative source, many information seekers turn to the most entertaining source. One such example is "The Daily Show with

Jon Stewart." Can you think of other examples? Please discuss the advantages and disadvantages of this type of information seeking behavior as it relates to section

5.5, "Information versus Entertainment" in Case.

In general, the class agreed that entertaining materials can be valid sources of information, with a few caveats.

QUESTION 1 SUMMARY:

Advantages:

-may provide motivation to seek out further information

-information may be better recalled if presented in entertaining manner

-message may have greater impact

-appeals to different type of learner

-non-stressful way of gaining information

Disadvantages:

-important that the entertaining item not be the ONLY source of information

-difficult to determine what is true information and what is artistic license

-concerns about passivity of learning via entertainment

Examples:

-the "...for Dummies" series of self-help books

-films

-educational software

-reality tv, i.e., cooking or home repair programs

-public service advertisements

-educational tv, i.e., history programs

QUESTION 2:

Section 5.4.2 in Case, "Knowledge Gaps and Information Poverty," mentions that socioeconomic status is a factor that strongly influences knowledge acquisition. Do you agree with this assessment? As future librarians/information professionals, how do you propose to close the described knowledge gap in order to reach information poor populations?

QUESTION 2 SUMMARY:

Everyone in the class agreed that socioeconomic status of a given population influences knowledge acquisition. However, it is not the only factor--issues such as literacy skills, receptivity to information, mental ability, and access to resources are also important considerations.

A few students brought up the economic status of libraries as a limiting factor in what resources can be made available to the public. It was also noted that the library itself is an example of the "haves" taking responsibility for providing information opportunities to the "have-nots" in an attempt to bridge knowledge gaps.

A number of ideas were proposed that librarians can take to reduce the level of information poverty.

-being aware that there is an information gap

(see http://clinton4.nara.gov/WH/New/digitaldivide/digital3.html

(thanks Demetra))

-promoting library services to those with disabilities

-programs to improve adult literacy

-involvement in policy-making organizations at the local and national level

-creating a dialogue with media services/organizations

-improving access to information materials

-grass-roots organizations that promote the sharing of resources

(see http://www.readertoreader.org

(thanks Sara))

SELECT REFERENCES

Apted, S. (1971). General purposive browsing. Library Association Record, 73, 66-78.

Belkin, N. J., & Vickery, A. (1985). Interaction in information systems: A review of research from document retrieval to knowledge-based systems. Boston Spa, England:

British Library.

Chang, S., & Rice, R. (1993). Browsing: A multidimensional framework. In M. Williams

(Ed.), Annual review of information science and technology (Vol. 28, pp. 231-276).

Medford, NJ: Learned Information.

Chew, F., & Palmer, S. (1994). Interest, the knowledge gap, and television programming.

Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 38, 271-287.

Dervin, B. (1989). Users as research inventions: How research categories perpetuate inequities. Journal of Communication, 39(3), 216-232.

Gaziano, C. (1997). Forecast 2000: Widening knowledge gaps. Journalism and Mass

Communication Quarterly, 74(2), 237-264.

Maslow, A. H. (1963). The need to know and the fear of knowing. The Journal of

General

Psychology, 68, 111-125.

Miller, G. A., Galanter, E., & Pribram, K. H. (1960). Plans and the structure of behavior.

New York: Holt.

Mizzaro, S. (1998). Relevance: The whole history. In T. Hahn & M. Buckland (Eds.),

Historical studies in information science (pp. 221-243). Medford, NJ: Information Today.

Reagan, J. (1996). The "repertoire" of information sources. Journal of Broadcasting &

Electronic Media, 40, 112-121.

Ritchie, L. D. (1991). Information. (Vol. 2). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Rogers, E. M. (1986). Communication technology: The new media in society. New York:

Free Press.

Savolainen, R. (1995). Everyday life information seeking: Approaching information seeking in the context of "way of life". Library and Information Science Research, 17,

259-

294.

Sears, D., & Freedman, J. (1967). Selective exposure to information: A critical review.

Public Opinion Quarterly, 31, 194-213.

Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1995). Relevance: Communication and cognition. (2nd ed.).

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Toms, E. G. (1999). What motivates the browser? In T. D. Wilson & D. K. Allen (Eds.),

Information behaviour: Proceedings of the second international conference on research in information needs, seeking and use in different contexts, 13/15 August 1998, Sheffield,

UK (pp. 81-96). London: Taylor Graham.

Wilson, P. (1995). Unused relevant information in research and development. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 46, 45-51.

Zillman, D., & Bryant, J. (1986). Exploring the entertainment experience. In J. Bryant &

D. Zillman (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 303-324).

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.