CCMAil: December 2006

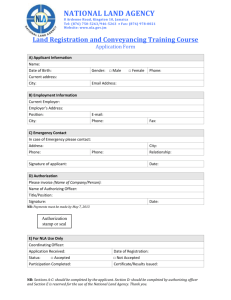

advertisement