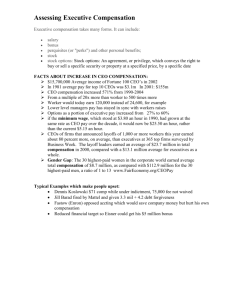

CEO Compensation Practices in Nonprofit Hospitals

advertisement

www.nonprofithealthcare.org Washington, DC 20018 877-299-6497 CEO Compensation Practices in Nonprofit Hospitals: A Matter for Pubic Concern and Action? Hardly a week goes by when there isn't a national, state or local news story raising concerns about compensation for chief executive officers (CEOs) or other executives of nonprofit hospitals or health systems. This special Alliance report summarizes the views of two nationally recognized experts on this important issue. The two experts--Ken Ackerman, Chairman of INTEGRATED Healthcare Strategies (INTEGRATED), based in Minneapolis, MN and David Bjork, Senior Vice President and Senior Advisor of INTEGRATED's executive compensation practice--shared their perspectives with the Alliance's President, Bruce McPherson, in June 2013. Basic Objectives in CEO Pay Practices The board’s fundamental goal in setting CEO pay is to pay what’s necessary to find and retain the best CEO to lead the organization. With that basic goal in mind, the board's practical objectives are to pay enough to maintain the CEO's morale, minimize controversies within the board over the CEO's pay, and make sure that decisions are defensible to regulators and others—such as the media, the general public, the medical staff, and the hospital's employees. Board Dynamics and the Competitive Labor Market Virtually all nonprofit hospitals and health systems are facing major challenges such as labor shortages, intense competition, and increasing financial risk for various dimensions of performance—quality, patient safety, patient satisfaction and efficiency. Such challenges have intensified the competition for talent—for CEOs and other executives—between independent hospitals and between regional and national hospital systems. Even with sector consolidation through mergers and acquisitions, the nonprofit hospital sector is still very much a cottage industry. For instance, with nearly 5,000 hospitals in the country, hospital CEOs typically progress in their careers by moving from smaller institutions to larger ones, from smaller systems to larger systems. CEOs often move three to five times in their careers. This leads to lots of turnover, crates lots of opportunities for CEOs to enhance their compensation, and forces boards to compete for talent. Boards have two strategic options for CEO recruitment. The first is to develop CEO talent internally; but independent hospitals and smaller systems tend not to do so, because they are organized in professional silos that don't develop general managers and because they can't afford to keep extra talent around in jobs designed as pathways to the CEO position. The organizations that are really good at developing CEO talent internally tend to be big, decentralized systems with six or more operating units. The second option is the path that most boards take: recruiting from the outside someone who has already been successful at doing the same job in a comparable organization. To do this they are willing to pay top dollar, which is often more than what the last CEO made. When it’s time to recruit a new CEO, boards want to minimize risk by choosing someone who has already proven capable of handling the job. It's hard to find a board or a search committee that would set as a criterion finding the best inexpensive CEO or the best young CEO--even though there may be many good ones who would be glad to take the position at lower pay than would a seasoned CEO from a comparable organization. Likewise, boards have only two strategic options for retaining their CEOs. The first is to let them move on whey they are ready to go—to recognize that, no matter how well they are paid, CEOs will move on if and when they want to move to enhance their careers or to live where they want to live. This can mean living with frequent turnover, as many small hospitals do. It can mean choosing or settling for a CEO who is likely to stay put for one reason or another. But it also means that boards are less likely to pay a lot just to retain the CEO, since it’s almost impossible to pay enough to hold onto a successful CEO who wants to move on or who is willing to move on to make more money. The second option is to try to pay enough to retain the CEO. The only way this works is to pay as much as bigger organizations are willing to pay to attract the CEO and to structure the pay package so the CEO would forfeit a lot by leaving. Even then, another organization is likely to be willing to cover the forfeiture with a hiring bonus. Unfortunately, many boards fall into the trap of paying a lot to retain the CEO (and other executives as well), hoping that the CEO will stay as long as the board is generous. Just as boards want to minimize risk in recruiting, they want to minimize the turmoil and stress caused by CEO turnover, and that often leads them to pay more than what the organization’s compensation philosophy calls for—paying as much as they dare, as much as they believe is reasonable, in order to retain an executive who is performing well, Public Concerns: Warranted or Not? Boards pay what they have to pay, or what they believe they need to pay, to recruit and retain good CEOs. They no doubt believe that they are paying no more than they need to, and that what they are paying is entirely reasonable. They generally obtain reasonably good information and advice about pay levels in the industry. Sophisticated boards generally exercise considerable discipline in following best practices in governing executive pay and in meeting the requirements for the presumption of reasonableness. Nonetheless, a few federal and state government officials, most notably Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley, have recently questioned the value of the "rebuttable presumption of reasonableness" established by Congress and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to strengthen governance of executive compensation by boards of organizations exempt from taxation under section 501 (c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Organizations meeting the requirements for the presumption are in effect provided a "safe harbor" from IRS sanctions on excess compensation. The requirements include (1) approval in advance by an authorized body (i.e. compensation committee), the members of which have no conflict of interest with regard to executive compensation; (2) reliance on appropriate comparability data on total compensation paid by comparable organizations for comparable positions in comparable situations; and (3) adequately documenting in timely minutes the terms 2 approved, the process followed, and the basis for determining that the compensation approved is reasonable. The critics argue that the presumption provides an easy pass for boards that pay executives too much—an easy way to justify excessive pay, a lot of busy work to paper over the problem. They point out that boards and their consultants can rig a peer group to provide whatever data is needed to demonstrate that compensation is reasonable, and that any board or compensation committee can go through the motions and document its decisions in timely minutes. Much of the criticism of executive pay in not-for-profit healthcare organizations is based on figures reported in IRS Form 990, which requires reporting compensation in ways that misrepresent actual compensation. The instructions require double-reporting of deferred compensation, and the biggest figures reported virtually always represent vesting of retirement benefits earned over many years. What gets reported in the press is often badly misconstrued— total compensation being reported as “salary,” for example. What the critics miss is that boards have been entrusted by law with governing those tax-exempt organizations, entrusted to make all kinds of decisions, many of them more important than decisions about executive compensation. What they misunderstand is that most boards are well intentioned, and that it is those good intentions that lead to generous pay. All the boards are trying to do is pay as much as other organizations do, so they can attract and hold onto leadership talent. There is nothing wrong, after all, with paying competitively, or with paying enough to recruit the leaders you need to be successful, or paying enough to keep them from going somewhere else for more pay. The criticism of use of peer group data in setting compensation doesn’t make much sense in healthcare, with all the turnover and movement from one organization to another. The labor market for healthcare executives is pretty clearly defined: it is a broad market—either a broad regional market or a national market—of other organizations about the same size, with comparable services and comparable challenges. It is only small rural hospitals that look only or primarily at in-state data in setting executive pay. Other hospitals and health systems almost all look at national data, because that best represents the labor market in which they compete for talent. We should point out something often overlooked by the media, that the overall rate of increase in CEO pay in the nonprofit health sector is averaging only about 3%--no higher and perhaps lower than salary increases for other employees, such as nurses and pharmacists. Possible Actions Boards are increasingly sensitive to public scrutiny--from regulators, the media, unions, employees and others. Better board education, more transparency, and perhaps some regulatory "tweaking" could help strengthen governance of executive pay in nonprofit health care organizations. One of our suggestions is that there be even more disclosure of compensation practices, especially regarding the organization's compensation philosophy, the peer group it uses in determining pay, and the nature and extent of incentive and retirement programs. This is already required in the for-profit sector. The Securities and Exchange Commission now requires publiclytraded firms to describe their approach to selecting comparability data and disclosing whether, as part of their executive compensation philosophy, they set pay at the median, the 75th percentile or some other percentile. Requiring disclosure of this sort of information could be very helpful in deterring overly generous compensation philosophies. 3 Another suggestion is that nonprofit health care boards should seriously consider the elimination of defined-benefit supplemental executive retirement plans (SERPs) for CEOs and other executives, as most employers have eliminated final-average-pay pension plans for other employees. Pensions for other employees used to require 30 years of service to get maximum credit, but SERPs for executives typically deliver maximum value after only 20 or 25 years of service. Retirement benefits based on final-average pay make even less sense for highly-paid executives than for other employees, since executive pay at the end of a career is generally much higher than it was 15 or 20 years earlier, and since few CEOs serve much more than five or 10 years before retiring from their final CEO position. Providing a lifetime retirement benefit of 50% of final average pay after 25 or 30 years of service might make sense for a nurse or a housekeeper, and it might make sense for someone who has been CEO for 25 years, but it makes no sense for someone who was CEO for only 3 years, after 25 years in lower-paid positions. Other suggestions we have for nonprofit health care boards to consider: Limit severance pay to 12 or 18 months, to avoid having to pay fired CEOs full salary or full pay for 2 or 3 years; Avoid bizarre benefit designs intended only to reduce a well-paid executive's tax obligations; and Forget about "keeping up with the Jones's." Stop worrying about what everyone else does and do what’s right for your own organization. Don’t get trapped in thinking that you always have to pay more than you did last year— another salary increase, maybe a bigger one than last year, and just as big a bonus or even more than last year. There are no magic bullets, however, to make the issue go away. Executive compensation is always going to look high to most people, since most people are paid a lot less than executives. The fundamental public policy question comes down to whom would you rather trust to make these decisions--some government official or agency or the independent board members of these nonprofit health care organizations? We opt for the latter without hesitation. They bring community values and perspectives to bear on decisions; they have to defend their decisions to their local communities; and they know what it takes to recruit and retain executives in a highly competitive labor market. Nonprofit health care boards include some of the most prominent leaders in their communities, often CEOs or other executives of local businesses. If we entrust them with making good decisions about the best ways to meet the health care needs of their communities, why shouldn’t we trust them with making good decisions about executive pay? 4