Contents - Judicial College of Victoria

advertisement

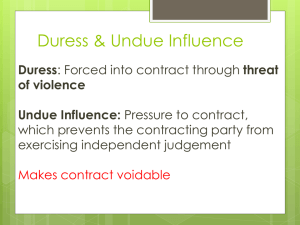

8.11.1 - Common Law Duress1 8.11.1.2 - Charge [This charge should be given if there is evidence from which a jury might infer that the accused was acting under duress when s/he: Committed an offence other than homicide before 1 November 2014; Committed a homicide offence other than murder2 before 23 November 2005; or Committed a homicide offence other than murder on or after 23 November 2005 and before 1 November 2014, and it is necessary to rely on common law duress as well as, or instead of, statutory duress (see Bench Notes: Statutory Duress (Topic Not Yet Complete) for assistance). The charge should be given immediately after directing the jury about the relevant offence.] Introduction In this case the defence alleged that NOA was acting under duress when s/he [insert relevant act]. I therefore need to give you some directions about “duress”.3 The defence of duress was introduced into the law a long time ago as a concession to human frailty. It is based on the recognition that sometimes people of ordinary firmness of character will commit crimes to avoid a threatened harm. While their actions may not be justified, the law excuses them from responsibility given the circumstances. This means that, even if you are satisfied that the prosecution has proven all of the elements of [insert offence] beyond reasonable doubt, NOA will not be guilty of that offence if s/he acted under duress. Because the prosecution must prove the accused’s guilt, it is for the prosecution to prove, beyond reasonable doubt, that NOA was not acting under duress. It is not for NOA to prove that s/he did act under duress. 1 This document was last updated on 1 November 2014. While it is clear that duress cannot be a defence to the actual killer, it is unclear whether duress is available as a defence to people who aid, abet, counsel or procure murder. See the Bench Notes for a discussion of this issue. 2 This charge only addresses the defence of duress. It is possible that the evidence in question may also have relevance to the determination of the elements (see, e.g., R v Darrington [1980] VR 353; R v Harding [1976] VR 129). 3 1 Unfortunately, it is always difficult to give directions about duress in a way which completely avoids any suggestion that it is a matter for the accused to prove. However, that is not the case. It is very important that you keep in mind at all times that it is the prosecution who must eliminate any reasonable possibility that the accused acted under duress. So before you can find the accused guilty of [insert offence], you must be satisfied, beyond reasonable doubt, that the prosecution has proven all of the elements of the offence and has negated the defence of duress. Elements of Duress There are seven ways in which the prosecution can negate the defence of duress. I will list them for you, and then examine each one in detail.4 First, the prosecution can prove that no-one was threatened with death or serious injury if the accused failed to [describe relevant offence]. Second, the prosecution can prove that any threat that had been made was not present and continuing, imminent and impending when the offence was committed. Third, the prosecution can prove that the accused did not reasonably apprehend that the threat would be carried out. Fourth, the prosecution can prove that it was not the threat that induced the accused to commit the offence charged. Fifth, the prosecution can prove that, when free from the duress, the accused voluntarily exposed himself/herself to its application. Sixth, the prosecution can prove that the accused could safely have prevented the execution of the threat. Seventh, the prosecution can prove that the circumstances were such that a person of ordinary firmness of character would not have been likely to yield to the threat in the way the accused did. If the prosecution can prove any of these matters beyond reasonable doubt, then they will have negated the defence of duress. In such circumstances, if you are also satisfied that the prosecution has proven, beyond reasonable doubt, all of the elements of [describe offence], then s/he will be guilty of that offence. I will now examine each of these matters in more detail. Threat of Serious Harm The first way the prosecution can negate the defence of duress is by proving If any of these methods of negating duress are not relevant in the circumstances of the case, they should be deleted and the charge modified accordingly. 4 2 that no-one was threatened with death or serious injury if NOA failed to [describe relevant offence].5 The prosecution alleged that that was the case here. [Summarise prosecution arguments and evidence. The charge should clearly identify whether the argument is (i) that no threat was made; (ii) that the threat was not of death or serious injury; and/or (iii) that the demand was not to commit the offence charged.] The defence denied this, arguing [summarise defence evidence and/or arguments]. Present, Continuing, Imminent and Impending Threat The second way the prosecution can negate the defence of duress is by proving that any threat that had been made was not present and continuing, imminent and impending when NOA committed the offence. In other words, if the prosecution can prove that the threat had ended by the time the offence was committed, or that nobody was in imminent danger at that time, the defence of duress will fail. [If the alleged threat was to commit harm in the future, add the following shaded section.] This does not mean that the threat must have been to harm [identify threatened party] immediately if NOA did not commit the offence. The defence of duress does not fail simply because the threat was to harm [him/her/someone else] in the near future. The issue here is whether the threat – whatever its nature – was still effective at the time the crime was committed. [If the threatener may not have been present at the time the offence was committed, add the following shaded section.] This does not mean that the person who made the threat must have been present when the offence was committed. The issue is whether the threat was still present and continuing at that time. Threats can still be present and continuing, even if the person who made them is not physically present.] The prosecution alleged that in this case, even if a threat had been made, it was not present and continuing, imminent and impending at the time the offence was committed. [Summarise prosecution evidence and/or arguments]. The defence denied this, arguing [summarise defence evidence and/or arguments]. Reasonable Apprehension The third way the prosecution can negate the defence of duress is by proving While not clear, it is possible that threats of lesser harm (e.g., imprisonment) may also be sufficient (see the Bench Notes). If the alleged threat was of such a nature, the charge should be modified accordingly. 5 3 that NOA did not reasonably apprehend that the threat would be carried out. This requires the prosecution to prove that NOA did not reasonably fear that [identify threatener] would actually [identify threat] if s/he did not [describe offence]. The prosecution alleged that that was the case here. [Summarise prosecution arguments and evidence. The charge should clearly identify whether the argument is (i) that the accused did not actually fear that the threat would be carried out; and/or (ii) that the accused did not have reasonable grounds for that fear.] The defence denied this, arguing [summarise defence evidence and/or arguments]. Threat Induced the Crime The fourth way the prosecution can negate the defence of duress is by proving that it was not the threat that induced the accused to commit the offence charged. This will be the case if the prosecution can prove that NOA committed that offence for any reason other than to avoid the threat being carried out. To have acted under duress, NOA must only have committed the crime because of the threat. In this case the prosecution alleged that it was not any threats made by [identify threatener] that caused NOA to [describe offence]. They argued that s/he committed that offence because [summarise prosecution arguments and evidence]. The defence denied this, arguing [summarise defence arguments and evidence]. [Where the accused’s knowledge of the threatener’s reputation may have influenced his or her response, add the following shaded section.] In determining whether NOA’s actions were induced by the alleged threat, you should consider the nature of the threats made, as well as NOA’s knowledge of the character and reputation of [identify threatener]. Voluntary Exposure to Duress The fifth way the prosecution can negate the defence of duress is by proving that, when free from the duress, NOA voluntarily exposed himself/herself to its application. This will be the case if, for example, the accused voluntarily joined or associated with a criminal organisation, or became party to a criminal enterprise knowing of its criminal purpose. In such circumstances, the accused cannot rely on duress as a defence to any offences s/he commits in response to threats arising out of his/her association with the organisation, or his/her participation in the criminal enterprise. Because s/he voluntarily put him/herself in a position where such 4 threats could be made, s/he is held responsible for the consequences. [If the accused may have been coerced into joining the relevant organisation or enterprise, or may not have known of its criminal purpose, add the following shaded section.] It is important to note that the accused must have voluntarily exposed himself/herself to the duress for the defence to be negated on this basis. This will not be the case if s/he [was coerced into joining the criminal organisation or enterprise in the first place / did not know that the organisation or enterprise s/he was joining had a criminal purpose]. In this case the prosecution alleged that NOA voluntarily exposed himself/herself to duress by [summarise prosecution arguments and evidence.] The defence denied this, arguing [summarise defence arguments and evidence]. Safe Escape The sixth way the prosecution can negate the defence of duress is by proving that NOA could safely have prevented the execution of the threat. In this case, the prosecution alleged that NOA could have done so by [describe the actions the accused could have taken to prevent the threat, e.g., “escaping when…” or “reporting the matter to the police”]. For the prosecution to succeed on this basis, it is not enough to prove that NOA could have [describe action]. The prosecution must prove that if NOA had done so, the threat would not have been carried out. They alleged that that was the case here. [Summarise prosecution arguments and evidence.] The defence denied this, arguing [insert defence arguments and evidence]. In determining whether NOA could safely have prevented the execution of the threat, you should consider what the reasonable person would have done in those circumstances. If you find that a person in those circumstances, and acting reasonably, would have [describe action], and by doing so would have prevented the threat being carried out, then the defence of duress will fail. In making this determination, you should have regard to all of the circumstances, including any risks associated with the proposed course of action. A person is only required to pursue an opportunity if s/he can do so with reasonable safety. You should also take into account the fact that the circumstances may not have provided the accused time to give calm and measured consideration to the course of conduct that was open to him/her. Person of Ordinary Firmness Would Not Have Yielded The seventh way the prosecution can negate the defence of duress is by 5 proving that the circumstances were such that a person of ordinary firmness of character would not have been likely to yield to the threat in the way the accused did. For this to be the case, the prosecution must prove that a person with the ordinary powers of self-control of an [describe accused’s age and sex, e.g., “adult male”], who was placed in the same situation as NOA, would not have been likely to give in to the threats by committing [describe offence]. In determining this issue, you should consider the nature of the threats and the proportionality of those threats to the crime committed. You should also take into account anything that NOA knew about [identify threatener], which may have affected the ordinary person’s reactions to the threat. In this case the prosecution alleged that, in the circumstances, a person of ordinary firmness of character would not have been likely to yield to the threat in the way NOA did. [Summarise prosecution arguments and evidence]. The defence denied this, arguing [summarise defence argument and evidence]. Summary To summarise, even if you decide that all of the elements of [insert offence] have been proven beyond reasonable doubt, you may find that NOA was not guilty of that offence because s/he was acting under duress. Before you can find NOA guilty of [insert offence], you must therefore be satisfied not only that all of the elements have been met, but also that the prosecution has proven, beyond reasonable doubt, at least one of the following seven matters: One – that no-one was threatened with death or serious injury if NOA failed to [describe relevant offence]. Two – that when that offence was committed, any threat that had been made was not present and continuing, imminent and impending. Three – that NOA did not reasonably apprehend that the threat would be carried out. Four – that it was not the threat that induced NOA to commit the offence charged. Five – that, when free from the duress, NOA voluntarily exposed himself/herself to its application. Six – that NOA could safely have prevented the execution of the threat; or Seven – that the circumstances were such that a person of ordinary firmness of character would not have been likely to yield to the threat in the way NOA did. If the prosecution cannot prove at least one of these matters beyond reasonable doubt, then you must find NOA not guilty of [insert offence]. 6 7