Persuasion and attitude change

advertisement

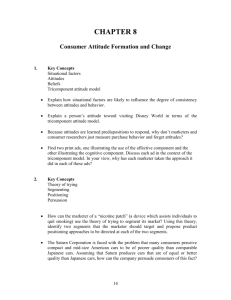

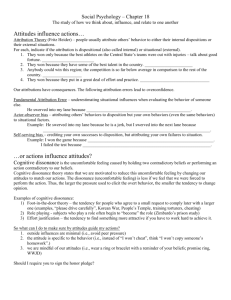

Persuasion and attitude change An attitude is a ‘posture or position’. It incorporates the following aspects: • • • • • Generally or entirely learned Relatively permanent Concerned with affect (feeling) Governed by consistency Determines behaviour Attitudes are generally held to have 3 components: • • • Affective: An affective aspect of liking/disliking, based on Cognitive: Beliefs (cognitions) about the object, which Behavioural: Leads to a readiness to behave in a certain way Hovland-Yale Model The Yale persuasion model suggests the degree of attitude change produced by persuasive communication depends upon many important variables, including source factors relating to the communicator of the information, message factors relating to the content and style of the communication itself, audience factors relating to the recipient of the message and the situational factors relating to the context the communication occurs in. Context More informal environments seem to induce more attitude change than formal contexts. Communicator Source factors of communicators: • • • Credibility, (expertise, knowledge) Trustworthiness (motives, beliefs) Likeability (attractiveness, charm, status and race) Evaluation Studies show equal learning from high and low credibility sources, but more acceptance of information from high credibility sources (although this effect was relatively short-lasting). Attractive, charming, high-status, and same-sex sources increase persuasion. A2 psychology media M. Bird Communication Message factors of presentation. • • • • Spelling out conclusions One or two-sided arguments Order of presentation Use of emotion Evaluation Studies fine one-sided arguments spelling out conclusions more effective with complex messages and low education audiences, but better-educated ones are more influenced if left to draw their own conclusions. Information presented first (primacy effect) and avoiding extreme use of emotion appeal is more effective. Audience Recipient factors include: • • • Level of education/intelligence/knowledge Resistance to persuasion/strength of initial attitudes Level of audience participation Evaluation Studies show greater attitude change with higher audience participation, but weaker initial attitudes/resistance. Educational level interacts with source and message factors. Elaboration-likelihood model (ELM) Petty and Cacioppo’s (1981, 1986) ELM suggests the degree of persuasion and attitude change depends upon the probability (likelihood) that people will devote mental effort to (elaborate upon) the information they receive about an issue or product. Motivation/ability to elaborate People’s elaboration increases when: • • • • The issue/product is highly important or relevant to them. They are solely responsible or accountable for decisions They are ambivalent or uncertain They have greater intelligence, time and freedom from distraction A2 psychology media M. Bird Persuading/advertising technique When elaboration-likelihood is high, persuasion depends on high-quality arguments, attitudes are changed by issue/product information When elaboration-likelihood is low, less effortful tactics not directly concerned with the product itself are effective in changing attitudes. High motivation/ ability to elaborate = greater scrutiny of issue/product information Low motivation/ ability to elaborate = less scrutiny of issue/product information Elaboration-likelihood continuum Peripheral route to persuasion Central route to persuasion Low mental effort or indirect persuasion straties, e.g. simple slogans about the issue/product or repeated (classical conditioning) association with pleasant stimuli. Reasoned arguments and detailed information about issues/products are provided to a motiavated listener who is able to consciously consider the advantages and disadvantages Evaluation The peripheral route techniques often produce weaker attitude change, poorly thought-out decisions (e.g. basd on superficial characteristics or the number rather than quality of arguments) and other negative effects (e.g. reinforcing stereotypes). The ELM has been supported by attitude change studies that vary the quality of arguments and exposure time to messages. A2 psychology media M. Bird The influence of attitudes on decision making An individual’s positive or negative attitudes (or more specifically, the cognitive and affective components of attitudes) are thought to play an important role in that person’s decision making and eventual behaviour. Those who wish to affect decision making and behaviour (e.g. advertisers or governments) have therefore tried to use persuasion techniques to change attitudes and have found it useful to take into account the roles of cognitive consistency/dissonance and self-perception. The role of cognitive consistency/dissonance What are cognitive consistency/dissonance? You're walking down a busy street deep in your own private thoughts. All of a sudden a smiling woman jumps out of somewhere, stands in front of you, and puts a flower in your hand. "Hello dear... isn't it a wonderful day today? I want you to have this flower!" she says. Now you have a beautiful flower in your hand. It's a nice gift and she seems friendly. She begins to walk with you, telling you that you have nice, kind eyes. She says she noticed right away that you were special and so wanted to meet you. You forget your previous thoughts about work, bills or your own life. Suddenly you feel good... appreciated... uplifted. Then, in the same friendly voice and bright smile, she says, "I know you are a good person and you can help me by giving me a something for the beautiful flower -- right?" What happens inside your head at that moment is cognitive dissonance. Festinger (1957) suggested that cognitive dissonance is a feeling of unpleasant arousal experienced when an individual simultaneously holds two cognitions or attitudes that conflict (are inconsistent) with each other. The arousal acts like a drive state to motivate attempts to restore cognitive consistency and reduce dissonance. Festinger and Carlsmith (1959) Participants were involved in a very boring task (turning pegs in a board). They were then asked to tell another participant who was waiting to do the task tat the task was very interesting. Some participants were paid $20 dollars others $1. When they were asked to rate the task the more highly paid participants rated the task as boring whereas the low paid said it was enjoyable. The high paid have a reason for lying so they experience no dissonance, whereas the low paid have to overcome their dissonance by adjusting their assessment of the task. A2 psychology media M. Bird Cognitive dissonance can be reduced by: • • Changing attitudes or behaviour to eliminate the inconsistenc (the desired goal of persuaders). Dealing with the dissonance in another way e.g. attributing it to external influences (Festinger and Carlsmith 1959), minimising its importance or distracting oneself with unrelated behaviour such as drinking alcohol (Steele et al 1981) How can dissonance affect attitudes? Persuaders who wish to change attitudes and so decision making should thus aim to introduce or increase dissonance with an effort to control non-attitude change solutions. • • For example, anti-smoking campaigns have used images of the blackened lungs of dead people to increase the dissonance between th inconsistent (n non-suicidal smoers) cognitions ‘I smoke’ and ‘smoking kills’. Additional statements such as ‘onlyy you are responsible for your own health’ or ‘you can quit’ and presenting figures on the number of smoking-related deaths may help prevent individuals dealing with the dissonance by blaming other people and addiction or minimising it (although smokers outside pubs may still go back inside and try to drink the dissonance away!) Evaluation A number of studies have shown that more positive attitudes (towards initially counter-attitudinal issues or subjects) can be induced by introducing dissonance, for example by: • Having people eat grasshoppers after a request from a dislikeable person (Zimbardo et al 1963) caused more positive ratings of the experience (‘Why would I have done that unless it was not too bad’). Petty et al (2003) point out that, although studies have measured the physiological arousal from dissonance (e.g. Losch and Cacioppo 1990) and supported its subjective unpleasantness (Elliot and Devine 1994) dissonance: • • May not always be due to pure cognitive inconsistency – even proattitudinal behaviour can cause dissonance if it has unintended negative consequences (cooper and Fazio 1984) Is strongly affected by an individual’s self-perception and dissonance) A2 psychology media M. Bird The role of self-perception Petty et al (2003) review a variety of theories on the role of self-perception in dissonance and attitude change, but conclude the evidence for each is mixed and they are so flexible that they are better at explaining than predicting research result. Self-inconsistency theory Aronson (1969) argued dissonance stems from inconsistency between one’s self-view and one’s actions, e.g. ‘I am a vegetarian, but I am eating a hamburger. Self-inconsistency theory predicts people should prefer self-consistent feedback even if it is negative. Self-affirmation theory Steele (1988) suggests dissonance results from any threat to viewing oneself as morally adequate, e.g. I am a good person but I am doing something bad. Self-affirmation theory predicts people prefer positive feedback even if it is inconsistent with their self-view. Self-standards theory Stone and Cooper (2001) suggest dissonance results from behaviour that breaks the normative social values or idiographic personal values that are relevant to each individual. Self standards theory predicts less dissonance on issues irrelevant to the person, but more on issues applying to all in society. Evaluation Other self-theories have been proposed that do not require dissonance effects to account for attitude change, e.g.: • • Self-perception theory (Bem 1965) suggests people infer their attitudes from their behaviour so no dissonance occurs. Impression management theory (Tedeschi et al 1971) argues that attitude change results from the desire to appear consistent. A2 psychology media M. Bird A2 psychology media M. Bird