Word - Antioch University Seattle

advertisement

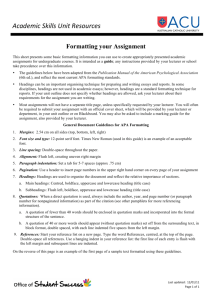

Running head: STYLE GUIDELINES 1 Style Guidelines for Writing Academic Papers Paul David, Ph.D. Ann B. Blake, Ph.D. Antioch University Seattle School of Applied Psychology, Counseling, and Family Therapy January 2, 2013 STYLE GUIDELINES 2 Table of Contents TOPIC APA Style Guidelines AUS Style Guidelines Academic Writing Format of Paper Organization of Paper Citations in Paper (1) Short Quotes (2) Long Quotes (3) Paraphrasing (4) No Page Number (5) Author's Name (6) Multiple Authors (7) Same Year Publication (8) Class Handouts (9) Secondary Sources (8) Person Communication References (1) Journal Article with One Author (2) Journal Article with more than One Author (3) Book (4) Edited Book (4) Chapter in Edited Book (5) Unpublished class handout (6) Electronic Media (7) Digital Objective Identifiers Writing Style Errors (1) Formatting Errors (2) Grammatical Errors (3) Punctuation Errors (4) Citation Errors Conclusion References Appendix A: Academic Writing Tips (1) Improved Writing Style (2) Structural Parameters for Academic Papers (3) Specific Grammar Guidelines about Comma Usage (4) Eliminate Specific Words/Phrases in Academic Papers Appendix B: Headings for Academic Papers Sample Paper PAGE(S) 3 4 4 4 5 6 6 6 7 7 7 8 8 8 8 9 9 9 9 9 10 10 10 11 11 12 12 13 15 17 18 18 19 19 19 19 20 21 1 STYLE GUIDELINES 3 Style Guidelines for Writing Academic Papers Writing involves two general components: content and style. Content pertains to the subject matter of a document; style refers to the particular standards that are used to structure and organize the content of a document. This document is concerned with the writing style standards and guidelines most commonly used for writing academic papers in the social sciences. The term “social sciences” refers to a plurality of academic fields outside of the natural sciences concerned with societal issues. These fields include anthropology, economics, history, political science, sociology, and psychology. Common style guidelines in these fields are established to promote clearly written communication. By setting explicit rules governing composition and format, style guidelines minimize problems of inconsistent expression as well as assist readers to give their full attention to the actual content of a manuscript. This document offers several forms of guidance to students writing academic in the social sciences. First, it sets forth basic style guidelines in the current edition of the American Psychological Association's (2010 Publication Manual. Second, it provides special guidelines, some of which are different from those in the current Publication Manual, for writing academic papers in the social sciences at Antioch University Seattle (AUS). Third, it also points out the most common style errors that are made in writing these types of academic papers. Because we value sustainability and accessibility, this document is single-spaced rather than double-spaced as required by the Publication Manual. Again, see the attached Sample Paper at the end of this document for examples of correct formatting for academic papers submitted to AUS instructors. The Publication Manual also provides useful sample papers that are available at www.apastyle.org for downloading. APA Style Guidelines The style guidelines provided by APA are drawn from an extensive body of social science literature, from editors and authors experienced in these fields, and from recognized authorities in publication practices in the social sciences. Writing in APA style, then, provides a format and composition mode that is both accepted by and familiar to a broad readership in the social sciences. In this sense, writing in APA style is a crucial aspect of being a scholar and professional in the social sciences. In the current edition of the Publication Manual, several opening chapters specifically address structure, writing style, and mechanics of style. Chapter two outlines and describes the structure of a formal paper. Chapter three describes issues such as organization, writing style, reducing biased language, and grammar. Chapter four offers specific information about mechanical skills in writing: punctuation, spelling, capitalization, italics, abbreviation, and a variety of guidelines for the use of numbers. We urge all students to read these chapters for an overview of concepts and specific formatting; once oriented to these style guidelines, students can then access the Publication Manual as a reference source for details and specific formatting. STYLE GUIDELINES 4 AUS Style Guidelines The intent of this document is to provide an initial introduction to some of the established style guidelines for format, citations, quotations, and references in academic papers. Many other style considerations not addressed in this document can be readily found in the Publication Manual. The Publication Manual serves as the guideline for submitting professional journal articles for publication in professional journals. Because academic papers are less formal than published journal articles, the Style Guidelines presented here intentionally modify some of the Publication Manual’s guidelines. Academic Writing. Academic writing is a type of formal discourse that addresses a particular topic relevant to scholarly disciplines. Academic writing differs from other forms of writing in a number of important ways. Some of these differences include: 1. In academic writing students’ statements, arguments, ideas, and opinions are supported from sources drawn from the relevant scholarly literature and research pertinent to the topic being discussed. Informal sources, such as magazines and Wikipedia, are typically not used or cited in academic writing. 2. Academic writing style relies on the precise and logical expression of ideas. Syntax and sentence structure are straightforward. In contrast to creative writing, academic writing uses a minimum of innovative syntax or descriptors. 3. Using colloquial, informal, and slang phrasing is frowned upon in academic writing. Chapter three in the Publication Manual lists many words and phrases to avoid in academic writing. 4. Above all, academic writing involves the presentation of informed argument; that is, academic writing relies on the use of evidence and reason to advance or present ideas about scholarly subjects. Format of Paper Papers should be typed using standard typefaces such as Times Roman, Courier, and Palatino. The size of the type should be 12 points. Use one space after each punctuation mark. For example, use one space after the sentence-ending period, one space after colons and semicolors, and one space after each of the initials in authors’ names. All new pages begin on the first line at the top of the page. Each line for the entire document, including the reference section, should be double-spaced. In this format, leave one full-size blank line between each line of type on the page. Also leave uniform margins of at least one inch at the top, bottom, right, and left of every page. Given these parameters, no more than 27 lines of text should be on any single standardized (8.5 x 11 inch) page. For the most part, word processing systems format to these specifications. When a single line or heading appears at the bottom of a page, use formatting tools to move that hanging line to the following page. All papers should have a separate cover page. See the first page of the main document as well as the Sample Paper at the end of this document for examples of correct formatting. Because the Publication Manual guidelines for cover pages address publication manuscripts, the STYLE GUIDELINES 5 guidelines for the cover page give sparse information. For papers submitted to AUS instructors, the cover page designates the following information to adequately identify the paper title, author, class, university, instructor (with academic credentials), and date submitted; these items are placed in consecutive order and in double-spaced format in the upper center section of the page. Beginning with the cover page, all pages use the “running head” format, formatted via software header tools. The running head is an abbreviated title that is printed at the top of the pages of the manuscript. It is placed on the left margin; pagination indicators are placed on the right margin. The Running head format gives consistent information on all pages of the paper: CAPITALIZED ABBREVIATED TITLE OF THE PAPER on the top left margin and pagination on the top right margin. Organization of Paper One metaphor to describe the organization of the content of an academic paper is the image of an upside down triangle (M. Rothaus, personal communication, January 10, 2010). At the top of the image, the platform of the triangle refers to broad descriptors used in the introduction section (no heading); the introduction includes a brief description of topics addressed in the paper as well as a general orientation to the specific assignment. Following the triangle downward toward the apex, the next sections of the paper describe and explore assignment criteria. Use headings to identify different sections of the paper. Depending on the type of heading levels used, headings consist of a combination of centered/left flush and bold and italics styles (see Appendix B). The apex of the triangle represents the conclusion section of the paper; this section briefly summarizes the main points of the paper as well as the author’s final perspective. The main text of an academic paper begins on the page following the cover page. The beginning of the text opens on the top line of the page, once again giving the title of the paper (not in bold style). The introductory section does not carry a heading labeling it as an introduction because the first section of the paper is assumed to be the introduction. These introductory remarks describe the specific topic(s) discussed in the paper. After the introduction, appropriate headings should then be used throughout the paper to distinguish various topic areas being discussed. Headings typically consist of one to three key words that define the topic areas. Headings orient the reader to the content of the paper via an organizational outline. Headings are never designated with numbers or letters. Depending on the number of levels used in the paper, all headings (with exception of the paper title on the second page of the paper) use a combination of centered/flush left and bold and italics styles (see Appendix B). In the text sections of the paper, all paragraphs should be indented; that is, the first line of every paragraph should be indented five spaces or approximately 1/2 inch from the left margin. After the first line, the remaining lines of the paragraph should be uniformly typed from the lefthand margin, leaving the right margin uneven. Single sentence paragraphs are too abrupt; a paragraph is composed of at least two sentences. However, avoid long paragraphs that tend to lose readers’ attention. A paragraph longer than one double-spaced page is usually too long. STYLE GUIDELINES 6 Run-on sentences also lose readers’ attention. A complete sentence usually addresses only one thought, concept, or idea; related sentences can be connected yet separated via a semi-colon (as in this sentence). When a page ends with a heading or a single-line of text, use formatting tools to move that hanging line to the following page. Although APA does not require a conclusion section at the end of papers, a conclusion strengthens and provides clarity. For most formal academic papers submitted to AUS faculty members, include closing comments in the conclusion section (use heading in bold style). A conclusion section concisely summarizes the points made in the paper as well as offers the author’s final subjective perspective about the themes addressed in the paper. Academic papers end with a separate reference page called References. The References page alphabetically lists all sources cited in the paper. Note that the References list cites only those works mentioned in the paper and should not be confused with a bibliography which cites works for background or for further reading. The “personal communication” citation appears only in the text of the paper and does not appear on the References list. Guidelines for formatting the References page are provided in the last section of this guide. Citations in Paper When directly quoting from another work, cite the source in the text by indicating the surname(s) of the author(s), the publication year of the source, and the location reference (i.e., the page or paragraph number) for the source. Short quotes. Source material quoted from an author’s work should be reproduced word for word. To incorporate a short quotation (fewer than 40 words) in the text of the paper, enclose the statement with quotation marks and indicate the page number or paragraph number (Internet sources) in parentheses as shown in the first example below. Example. According to Blake (2010), “People who know APA style live overall happier lives” (p. 2). Long quotes. To use a longer quotation (40 or more words) in the text, place the statement in a free-standing block of double-spaced lines; apply a five-space indentation from the left margin and omit the quotation marks. Place the page number(s) or paragraph number(s) in parentheses after the period ending the quotation. Example. Ward (2000) found the following: The “placebo effect,” which had been verified in previous studies, disappeared when behaviors were studied in this manner. Furthermore, the behaviors were never exhibited again, even when actual medications were administered. Earlier studies (e.g., Hoshino, 1996; David, 1995) were clearly premature in attributing the results to the placebo effect. (p. 275) STYLE GUIDELINES 7 Note that the comma after the words “placebo effect” in the first sentence is placed inside the quotations marks. Without exception, commas are always placed inside the quotations marks. For block quotations, place the parenthesized page number(s) after the period at the end of the last sentence. As in the rest of the text in the document, longer block quotations are doublespaced. Paraphrasing. When paraphrasing or referring to an idea contained in another work, APA’s (2010) Publication Manual states that identification of location references is “encouraged. . .especially when it would help an interested reader locate the relevant passage in a long or complex text” (p. 171). In AUS academic papers, indicate location information (i.e., the page or paragraph number) for both quoted and paraphrased information. Example. According to David (2012), students at Antioch are highly motivated learners (p. 43). Note that the period is used after the “p” and followed by a space; the period designated to close the sentence is located after the parentheses. Also note that the abbreviation for page is “p.” and not “pg.” The plural abbreviation for pages is “pp. No page number. When no page numbers are available for the citation, as is often the case in electronic sources, use paragraph numbers in the place of page numbers. Example. As Jones (2010) pointed out, “The current system of managed care needs major revision (¶ 3). Note that the ¶ symbol or the abbreviation “para” [without quotation marks] is used to designate the particular paragraph. Author’s name. When using author(s)’ name(s) in the text, place the year of the publication involved in parentheses. Example. David (2012) claimed that writing papers without APA guidelines creates problems for both the instructor and for students (p. 7). When author(s)’ ideas or research are referred to in the text without directly identifying author(s), place the author(s)’ name(s) and the date of the source at the end of the sentence and enclosed in parenheses. Example. Dance movement and horticultural therapy have been effective with some older Japanese American clients (Itai & McCrae, 1998, pp. 233-248). Note that although no direct quote is involved in the above reference, a location reference in the form of page numbers is provided to assist interested readers in finding this information. Also note that the period for the sentence is located after the citation. STYLE GUIDELINES 8 When citing articles with more than one author, use the “&” sign within parentheses and use the word “and” [without quotation marks] within the sentence. Example. David and Blake (2012) worked diligently to update this document. Example. Several authors (David, Blake, & Rothaus, 2012) worked diligently to update this document. Multiple authors. For multiple-authored citations, use the following formatting: Two authors: cite both authors in all citations. Three-five authors: cite all authors in the first citation: McBride, Lazarus, and Franklin (2010); in subsequent citations, use the following format: McBride et al. (2010). Six or more authors (e.g., David, Honda, Hoshino, Farley, Jones, Meggert, Saltzman, and Ward): use the following citation format: David et al. (2010). When the same idea comes from several sources, cite sources alphabetically rather than chronologically; use semicolons between the sources. Example. Multicultural and feminist therapists have challenged family therapy’s narrow definition of the family (Boyd-Franklin, 1990; Ho, 1988; Hong, 1997). Same year publications. When an author has written more than one publication in the same year, and both are cited in the text, label the first one “a,” the second one “b,” etc. Example. Psychologists need to be sensitized to symptoms of depression and alcohol abuse (Blazer, 1994a, 1994b). Class handouts. When accessing more than one class handout, list the sources on the References list by alphabetizing the citations according the first letter of the handout title. Similar to author(s)’ publishing more than one source per year, add a lower case letter (in alphabetical order) to the publication year; in the body of the paper, apply that format to distinguish between handouts. Page numbers are not usually used for course handout citations. Example. According to Bowen (as cited in David, 2012a), fusion involves unresolved emotional attachment with one’s family of origin. In contrast, Williamson (as cited in David, 2012b) described “psychological maturity” as giving up one’s parents as parents and relinquishing the need to be parented by them or by any of their designated substitutes (siblings, spouses, etc.). Secondary sources. When the author or research cited is contained in a secondary source, designate the primary source first and then its secondary source. Always place the designation of the secondary source immediately after the designation of the primary source. Example. According to Bowen (as cited in Kerr, 1989), avoiding triangulation in family relationships is a critical aspect of achieving greater differentiation as a separate person (p. 7). STYLE GUIDELINES 9 When using a direct quotation from a secondary source, use the same previously specified principle. Example. According to Keith and Whittaker (as cited in Goldenberg & Goldenberg, 2013), “We presume it is experience, not education, that changes families” (p. 209). Personal communication. When quoting or paraphrasing verbal information from interviews, conversations, and lectures, apply the following format for personal communication. This information is not included on the References list at the end of the paper. The format includes the person’s initials, surname, the phrase “personal communication,” and the actual date. Example. During a classroom lecture, the following point adds to my understanding of transpersonal psychology: human beings possess an innate capacity to move toward health (C. Ward, personal communication, March 5, 2012). Example. Rothaus described the innate human capacity to move toward health (C. Ward, personal communication, March 5, 2012). References All sources cited in the text, except those pertaining to personal communication, must be included in a separate section labeled References. These sources are listed in alphabetical order. When the same author is listed for more than one source, sources should be ordered by year of publication. To format the References section, place the first line of each reference flush to the left margin; for the second and succeeding lines, indent seven spaces in a hanging indent format. The following examples indicate the proper formatting for different types of references: Journal article with one author. Note that the author(s)’ first and middle initials are used (one space follows all punctuation marks: e.g., commas, periods, colons, semicolons). Italicize the title of the reference, making certain to capitalize only the following: the first word in the title, the first word in the subtitle of the article (i.e., the portion of the title following a colon), and proper nouns (e.g., American Psychological Association). The number “19” refers to the volume number and is also italicized. When the article citation also uses an issue (pagination is continuous throughout the calendar year), the citation is as follows: 19(2). Also note the following details: the volume number is italicized; no space between the volume number and the parentheses; the parentheses and the issue number are not italicized. The numbers “429-436” refer to the page numbers of the article and are not italicized; no pagination indicator (i.e., p. or pp.) is included in this citation format. Steiner, J. L. (1989). Psychotherapy with older women: Ageism and sexism in traditional practice. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 19, 429-436. Journal article with more than one author. Note that an ampersand precedes the surname of the last author in the series and that all of the words in the title of a journal are capitalized. STYLE GUIDELINES 10 Russo, N. F., Olmedo, E. L., Stapp, J. S., & Fulcher, R. (1991). Women and minorities in psychology. American Psychologist, 11, 1315-1363. Book. Note that for location of publication houses, use the name of the city followed by Postal Service state abbreviation of two capitalized letters. Meggert, S. S. (2009). Creative humor at work: Living the humor experience. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. Edited book. Note that for edited books, the abbreviation for editor (Ed.) or editors (Eds.) is placed after the author’s name with a period placed after the right parenthesis. The only capitalized words in a book title are the first word, the first word after a colon, and proper nouns. Comas-Diaz, L., & Greene, B. (Eds.). (1997). Women of color: Integrating ethnic and gender identities in psychotherapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Chapter in an edited book. Note that books editors’ surnames are placed after their initials in this case; one space follows all punctuation marks (e.g., commas, periods, colons, semicolons). Garcia-Preto, N. (2005). Latino families: An overview. In M. McGoldrick, J. Giordano, & N. Garcia-Preto (Eds.), Ethnicity and family therapy (3rd ed.) (pp. 153-165). New York, NY: Guilford Press. DVDs and Videos. Note that the producer, date, title, and company distributing the DVD or videotape are specified for this type of reference. McGoldrick, M. (2006). (Producer). The legacy of unresolved loss: A family systems approach [Videotape]. Available from Psychotherapy.net. Unpublished class handout. Note that in addition to the year of publication, the particular quarter that the handout was issued by the instructor is also designated. Also note that pagination is not usually used for course handouts. David, P. (2012, Fall Quarter). Bowen’s natural systems theory. Class handout from Family of Origin Systems. Antioch University Seattle. When accessing more than one classroom handout from the same instructor, list the sources on the References list by alphabetizing the citations according the first letter of the handout title. The following are samples of References list formatting for the above example: David, P. (2012a, Spring Quarter). Bowen’s natural systems theory. Class handout from Family of Origin Systems. Antioch University Seattle. STYLE GUIDELINES 11 David, P. (2012b, Spring Quarter). Williamson’s personal authority therapy. Class handout from Family of Origin Systems. Antioch University Seattle. Electronic media. Note that electronic media (e.g., the Internet) references begin with the same information that would be provided for a printed source (or as much of that information as is available). Electronic references, however, differ from printed sources in that a retrieval statement is provided at the end of the reference. This protocol is followed because documents from electronic media might change in content, location, or be removed from a site altogether. Also note that a period is not placed at the end of a retrieval statement (so that the entire address can be copied into the access line on search engines). A change from 2001 to 2010 Publication Manual is that electronic citations no longer require the exact retrieval date. American Psychological Association (2001, January 10). Electronic reference formats recommended by the American Psychological Association. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/journals/webref.html Rather than organized in a separate section, the Publication Manual includes electronic formatting with each of the types of sources (e.g., periodicals; books, reference books, and book chapters; technical and research reports). In addition to the usual citation format, electronic citations give the Internet access information (see example below). See the following example (APA, 2010, p. 200): Brody, J. E. (2007, December 11). Mental reserves keep brain agile. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com Digital object identifiers.The Publication Manual describes two types of Internet formatting for identifying internet sources. Uniform resource locators (URLs) organize notation components to map digital information on the Internet such as the following (APA, 2010, p. 188): Protocol http:// Host name www.apa.org/ Path to document Monitor/oct00/ File name of specific document Workplace.html In addition to the URLs, a recent innovation are digital object identifiers (DOIs) which provide a means of identification for managing information on digital networks. CrossRef, a DOI registration system, assigns clearinghouse information of a “unique identifier and underlying routing system” and “use the DOI as an underlying linking mechanism ‘embedded’ in the reference lists of electronic artless that allows click-through access to each reference” (pp. 188189). “We recommend that when DOIs are available, you include them for both print and electronic sources” (p. 189). “When a DOI is used, no further retrieval information is needed to identify or locate the content” (p. 191). The following examples of DOI citations are quoted from the Publication Manual (2010) in examples #1, #3, and #19 (pp. 198, 199, 203): STYLE GUIDELINES 12 Example #1 journal article with DOI: Herbst-Damm, K. L., & Kulik, J. A. (2005). Volunteer support, marital status, and the survival times of terminally ill patients. Health Psychology, 24, 225-229. Doi:10.1037/02786133.24.2.225 Example #2 journal article without DOI (when DOI is not available): Sillick, T. J., & Schutte, N. S. (2006). Emotional intelligence and self-esteem mediate between perceived early parental love and adult happiness. E-Journal of Applied Psychology, 2(2), 38-48. Retrieved from http://ojs.lib.swin.edu.au/index.php/ejap Light, M. A., & Light, I. H. (2008). The geographic expansion of Mexican immigration in the United States and its implications for local law enforcement. Law Enforcement Executive Forum Journal, 8(1), 73-82. Example #19 electronic version of print book: Shotton, M. A. (1989). Computer addiction? A study of computer dependency [DX Reader version]. Retrieved from http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/html/index.asp Schiraldi, F. R. (2001). The post-traumatic stress disorder sourcebook: A guide to healing, recovery, and growth [Adobe Digital Editions version]. Doi:10.1036/0071393722 Writing Style Errors Using APA style standards, as well as the more generally applied style guidelines in Hodges, Horner, Webb, and Miller (1998), this section discusses the most common errors students make in writing academic papers in the social sciences. Errors appear in many forms, but these errors can be generally classified into four categories: (1) format, (2) grammar, (3) punctuation, and (4) citations. Composition encompasses many other important and highly problematic aspects of writing style, such as organization and flow of the text. This section, however, is limited to the discussion of style problems in the above four categories which comprise the more technical and operational aspects of writing academic papers in psychology. Formating Errors Errors in formatting an academic paper typically involve spacing the lines in the narrative too closely together, placing too much text on one page, failing to place the running head and pagination via the formatting tools, labeling the introduction as an introduction, and providing no headings for specific sections of the paper. As APA standards indicate, each line of the paper should be double-spaced. This spacing format means leaving one full-size blank line (not a half or three-quarters) between each line of type on the page. Assuming uniform margins of at least one inch at the top, bottom, right, and STYLE GUIDELINES 13 left of every page, no more than 27 lines of text should be on any single standardized page (for the most part, word processing systems format pages to those specifications). Running head and pagination indicators are placed at the top of each page; placement is formatted via formatting tools. The running head is placed on the left margin; pagination indicators are placed on the right margin. No other places on the page are considered appropriate locations for these items. Because the first section of the paper is assumed to be an introduction, this section is never labeled as such. After the introduction, appropriate headings are used throughout the paper to distinguish various topic areas being discussed. Typically, headings consist of one to three key words that define the topic area; depending on level, headings use a combination of centered/flush left and bold and italic styles (see Appendix B). Without these headings, papers can be difficult to read and to evaluate. Grammatical Errors Grammar specifies the rules by which words are employed and arranged in sentences. The most typical grammatical errors include the improper use of verb tense, the lack of noun-pronoun and subject-verb agreement, incorrect placement of adjectives and adverbial clauses, and the lack of parallel construction in sentences. Past tense. Many problems with verb tense involve confusing present and past tense. The past tense should be used when referring to actions or conditions that occurred at a specific time in the past. For example, the past—not the present—tense should be used when discussing author(s)’ work or when reporting results from a study. INCORRECT: Blake (2009) finds that violence is far more prevalent in the workplace than previously had been reported. CORRECT: Blake (2009) found that violence is far more prevalent in the workplace than previously had been reported. Note that in the above and following examples there are words that are underlined, italicized, and/or CAPITALIZED for clarity. However, in academic papers these forms of emphasis are highly discouraged and the only exceptions to this are the title in running head format and headings styles. Active voice. In addition, when using the past tense, use active rather than passive voice as much as possible. PROBLEMATIC: The experiment was designed by Ward (2000). PREFERRED: Ward (2000) designed the experiment. In cases in which an action or condition did not occur at a specific time in the past, the present perfect verb tense should be used. INCORRECT: As a result of the research conducted at Antioch Seattle, a number of other institutions decided to get involved in similar types of investigations. STYLE GUIDELINES 14 CORRECT: As a result of the research conducted at AUS, a number of other institutions have decided to get involved in similar types of investigations. Subject-verb agreement. Beyond the problems of proper use of tense, the verb must also be in agreement with its subject despite intervening phrases that begin with such words as together, with, including, plus, and as well as. INCORRECT: The percentage of correct responses as well as the speed of the responses decrease with the amount of alcohol consumed. CORRECT: The percentage of correct responses as well as the speed of the responses decreases with the amount of alcohol consumed. Furthermore, the plural form of some nouns, particularly those that end in the letter a, may appear to be singular and often cause confusion in selecting the appropriate verb form. Two nouns often confused in this manner are data and phenomena. Both words are plural and should be accompanied by verbs in the plural form. Noun-pronoun agreement. Not only is noun-verb agreement a common problem, but noun-pronoun consistency is also often confused. The grammatical rule states that each pronoun agrees in number to the antecedent noun. INCORRECT: The group of students using the computer assisted program improved their diagnostic accuracy by 20%. CORRECT: The group of students in the computer assisted program improved its diagnostic accuracy by 20%. Adjectives and adverbs. Another area of grammatical difficulty involves the proper placement of adjectives and adverbial clauses so that they actually refer to the word they are supposed to modify. INCORRECT: The data from the most recent survey study (Farley, 2000) only suggest a partial answer to the question of which institution provides the most comprehensive clinical training program. CORRECT: The data from the most recent survey study (Farley, 2000) suggest only a partial answer to the question of which institution provides the most comprehensive clinical training program. INCORRECT: Based on the assumption that two heads are better than one, the two instructors decided to work together on the new curriculum. [This construction says, “the two instructors are based on an assumption.”] CORRECT: On the basis of the assumption that two heads are better than one, the two instructors decided to work together on the new curriculum. [This construction says, “the two instructors’ decision is based on an assumption.”] Parallel construction. Finally, the lack of parallel phrasing before and after coordinating conjunctions and among phrases in a series creates awkward sentences that are difficult to STYLE GUIDELINES 15 follow. The grammatical rule in this instance is to remain consistent in the construction of the phrases in these contexts. INCORRECT: The students in the training group were eager to get started and develop their clinical skills. CORRECT: The students in the training group were eager to get started and to develop their clinical skills. INCORRECT: The trainers told the trainees to make themselves comfortable, to read the instructions, and that they should ask about anything they did not understand. CORRECT: The trainers told the trainees to make themselves comfortable, to read the instructions, and to ask about anything they did not understand. Punctuation Errors The most typical punctuation errors involve the use of double quotation marks and commas. One of the most common mistakes made with double quotation marks is placement inside commas and periods when used to set off ironic comment, slang, or coined expression. Double quotation marks. Double quotation marks are always placed outside commas and periods in these cases. Note that these types of expressions are set off by quotation marks only the first time they are employed; thereafter, quotation marks should not be used with these expressions. INCORRECT: The students were “fit to be tied”. CORRECT: The students were “fit to be tied.” INCORRECT: Although the patient’s symptoms seemed “normal”, more diagnostic tests were nevertheless administered. CORRECT: Although the patient’s symptoms seemed “normal,” more diagnostic tests were nevertheless administered. Another common error in the use of double quotation marks is placing them after a page reference number when making a direct quotation. When a direct quotation is involved, the double quotation marks should always be placed at the end of the quotation and preceding the page reference number. INCORRECT: According to Jones (2000), “The most effective family therapists are not always the most well known family therapists (p. 10).” CORRECT: According to Jones (2000), “The most effective family therapists are not always the most well known family therapists” (p. 10). Commas. The most common mistakes in the use of commas involve errors of omission rather than commission. Most typically, these errors involve the failure to include a comma preceding a coordinating conjunction, following an introductory adverbial clause, following an introductory phrase, and separating items in a series. STYLE GUIDELINES 16 Conjunctions. A comma ordinarily precedes a coordinating conjunction that links main clauses. Coordinating conjunctions such as and, but, for, or, nor, so, and yet are used to connect two main clauses in a sentence. Note that when clauses are short (i.e., less than five words), the comma may be omitted before the use of these conjunctions. INCORRECT: The clinical consultant may or may not meet directly with the client but ordinarily he or she does not take actual charge of the case. CORRECT: The clinical consultant may or may not meet directly with the client, but ordinarily consultant does not take actual charge of the case. Adverbial clauses. A comma usually follows introductory adverbial clauses. These clauses modify the time, place, manner, cause, or degree of the main clause. Note that a comma may be omitted after an introductory adverbial clause, especially when the clause is short (i.e., less than five words), if the omission does not make for difficult reading. INCORRECT: When the principal diagnosis is an Axis I disorder this is indicated by listing it first. CORRECT: When the principal diagnosis is an Axis I disorder, this is indicated by listing it first. Introductory Phrases. A comma generally follows an introductory phrase. An introductory passage is often a prepositional or participial phrase. INCORRECT: In determining whether the sexual dysfunction is exclusively due to a general medical condition the clinician must first establish the presence of a general medical condition. CORRECT: In determining whether the sexual dysfunction is exclusively due to a general medical condition, the clinician must first establish the presence of a general medical condition. Series. A comma is always used to separate a series of three of more items, including the next to the last item. INCORRECT: Various parts of the limbic system have been associated with emotions, sex drive, eating behavior, memory and motivation. CORRECT: Various parts of the limbic system have been associated with emotions, sex drive, eating behavior, memory, and motivation. Semi-colons and colons. Semi-colons and colons, frequently used incorrectly, are sometimes inaccurately interchanged for the other. Semi-colons separate two related complete sentences; this usage does not include conjunctions. INCORRECT: Grammar rules are consistent and elegant; and once students understand these roles, accuracy increases. STYLE GUIDELINES 17 CORRECT: Grammar rules are consistent and elegant; once students understand these roles, accuracy increases. Semi-colons also separate a list of phrases that also include commas. INCORRECT: Assignments for graduate course work often include variations of practice sessions, videotapes, and transcripts, case presentations, reflection papers, and synthesis papers, or proposals, data collection, and data reporting. CORRECT: Assignments for graduate course work often include variations of practice sessions, videotapes, and transcripts; case presentations, reflection papers, and synthesis papers; or proposals, data collection, and data reporting. Colons. Colons separate a complete sentence from related examples; when the examples form a complete sentence, the first word following the colon is capitalized. INCORRECT: Grammar rules include a variety of specific usage; quotation marks, commas, semi-colons, and colons. CORRECT: Grammar rules include a variety of specific usage: quotation marks, commas, semi-colons, and colons. Colons also separate elements in citation formatting in References lists. INCORRECT: Seattle, WA; Antioch University Press. CORRECT: Seattle, WA: Antioch University Press. Citation Errors Several errors typically occur in making reference citations in the text of the paper. One of the most common errors is omitting the page number for a citation when a direct quote is involved. The page number from which the citation is taken should always be included when an author is directly quoted. INCORRECT: According to Honda (2009), “Adult learners are more responsible learners.” CORRECT: According to Honda (2009), “Adult learners are more responsible learners” (p. 4). When the author’s name is directly cited in the text, the page number is placed at the end of the quote and not in the parentheses after the year of publication. INCORRECT: According to Jones (2003, p. 1), “People who know APA style live overall happier lives.” CORRECT: According to Jones (2003), “People who know APA style live overall happier lives” (p. 1). STYLE GUIDELINES 18 Another common problem is incorrectly citing an instructor’s class handout. Although the reference section requires specifying the academic quarter of the document, a citation in the text of the paper should not include this information. INCORRECT: According to Bowen (as cited in David, 2002, Spring Quarter), fusion involves unresolved emotional attachment with one’s family of origin. CORRECT: According to Bowen (as cited in David, 2002), fusion involves unresolved emotional attachment with one’s family of origin. Another common error is employing a specific idea or term borrowed from another author without indicating or referencing this information. The ethical and scholarly requirements are very clear in this regard. Whenever another author’s ideas or concepts are used in the text, they must be referenced. INCORRECT: It appears that the client has mastered a position of learned helplessness. CORRECT: The client has apparently mastered a position of learned helplessness (Seligman, 1975). Conclusion This document provides a synopsis of the latest edition of the Publication Manual (2010) as well as an overall guide for writing academic papers in the social sciences at AUS. Although the Publication Manual designates the standards for writing articles for professional journals, this style guide sets forth the relevant standards drawn from the APA manual that AUS students can use to write academic papers. In reflecting these standards in their academic work, we hope that this guide will serve as a useful resource for AUS students to further their development and participation in scholarly discourse. References American Psychological Association. (2001). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Hodges, J., Horner, W. B., Webb, S. S., & Miller, R. K. (1998). Harbrace college handbook (13th ed.). New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. STYLE GUIDELINES 19 Appendix A Academic Writing Tips Improved Writing Style Graduate students’ papers usually meet standards for depth and breadth of content. In terms of structure, however, students too often employ phrasing that is colloquial and informal. The following tips provide general structural feedback that, when integrated, strengthen and clarify students’ academic writing. The basic criterion for improving academic writing is to elevate the narrative to a formal/academic tone by deleting colloquial/informal vocabulary and by substituting academic words and phrases in their place. Please attend to the following information which addresses specific issues in students’ papers. See also the section on Writing Style in Chapter 3 in APA's (2010) Publication Manual. Structural Parameters for Academic Papers (a) Always use two spaces (double space) between all lines; always follow punctuation marks with 1 space; (b) Never underline; bold and italics for headings only; exception: do not use bold style for the title of the paper on the first page of text; (c) Paragraphs = 2 or more sentences; (d) Spell out numbers when the numbers are the first word of sentences; (e) Use consistent font style and size throughout papers, including header information; When a heading and/or first line of a paragraph appear at the end of a page, move (f) that information to the following page via formatting tools. Specific Grammar Guidelines about Comma Usage (g) Separating two independent clauses with a conjunction: Summer days in Seattle are mostly sunny, but the clouds often block the full sun. (h) Following introductory dependent clauses: In 2009, we rewrote the writing overview. During August, 2009, contractors replaced the roof of the main building. (i) Seriation: a, b, and c. During 2009 in Seattle, the weather patterns included snow, rain, and sunshine. (j) With dates: August 28, 2009, marked the one-year anniversary. August, 2009, marked the one-year anniversary. (k) Running head: PC: (1) Cover page: Use Veiw/Header and Footer/Header: Running head: FULL NAME OF PAPER; (2) 2nd page through end of paper: Use File/Page Setup/Layout/Different first page: delete the words “Running head” for the remainder of the paper; continue the capitalized title. STYLE GUIDELINES 20 Eliminate the Following Words/Phrases in Academic Papers (1) (2) Spell out most abbreviations, except within parenthesis, for example e.g., and i.e. (e.g., spell out contractions): don’t do not. Eliminate colloquial/informal terms, e.g.: so; very; pretty; great; major; really; a lot; still; did; would; could; just; little; a lot; towards; amongst; fine. (3) Whether or not (4) Though/even though although (5) The fact that because (or just avoid this phrase) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) While = time: I am reading your papers while I drink a cup of tea. If not time-related, replace while with although: While Although: I am tired, I must complete this task. Since = time: I have not talked with you since class session last week. If not time-related, replace since with because: Since Because I am tired, I cannot complete this task. Feel that = cognition (think, believe, experience): I feel that believe that warm weather will eventually arrive. Feel = emotion (e.g., variations of sad, glad, mad, scared). Would = colloquial use: to denote repeated actions in the past. Academic voice: use past tense + specific time frame (e.g., During childhood, my parents often cooked breakfast together on Saturday mornings.) Avoid using “find/found” to describe your insight/experiences. There/it: do not use these words to start sentences or as the subject of sentences. (11) Use nouns rather than pronouns. When using pronouns, accompany all pronouns with a noun; do not use unaccompanied pronouns. (12) Though/even though although (13) Who/whom = people That = animals and inanimate objects (14) Ellipses: . . .indicates a gap within a sentence: Cloud forms. . .in the sky. . . . .indicates a gap between sentences: The rain streamed. . . .The sun hid behind clouds. Use one space between pairs of ellipses: word. . .word. (15) May = permission: You may use the phone. Might/can: = possibilities: You might use the phone, but you might decide to use email. You can use the phone or e-mail. (16) Who/what/when/how/why/where = question words; use only in sentences ending with a question mark. (17) If = possibility: If I get caught in the rain without an umbrella, I will get wet. When = actual event: When it rained, I was glad I remembered my umbrella. (18) Impact = noun, not verb (19) 1950’s; early 20’s 1950s; early 20s (20) Nouns and pronouns must agree: The student brought their laptop to class. The student brought her (or his) laptop to class. Students brought their laptops to class. (21) (22) STYLE GUIDELINES 21 Appendix B Levels of Headings for Academic Papers The general rule of thumb is that the appropriate number of headings for an academic paper will depend on the paper’s length and its complexity. Generally speaking, most academic papers minimally consist of Level 1 headings. This level divides up the paper into whatever number of sections are required for an assignment, or into whatever number of sections in which the student wishes to discuss his or subject material. Level 1 headings are centered, boldface, and in title case (where the first letter of the words are in uppercase and the remaining letters are in lowercase). An example of a single heading with this format is as follows: Family Structure When there are specific subtopics within the subject material, then it is appropriate to employ Level 2 headings. This level consists of the main headings as centered, boldface, and in title case and the subheadings in flush left, boldface, and in title case. An example of headings with this format is as follows: Family Structure Genogram Family Cohesion Regardless of the number of levels of subheadings within a section, the heading structure for all sections follows the same top-down progression accompanied by slightly different formatting for each additional level. For example, for a Level 3 heading, it is the previously designated formatting for the first two levels and indented, boldface, and lowercase paragraph heading ending with a period for the third level. An example of headings with this format is as follows: Family Structure Genogram Family Cohesion Enmeshed relationships. Disengaged relationships. There are heading formats for up to five levels, but most academic papers submitted to AUS instructors should be in the 1-3 level range. For examples of more complex heading formats, consult the Publication Manual. Nota Bene: When formatting headings, remember that the introduction at the beginning of the paper does not carry a heading that labels it as the introduction. Instead, the title of the paper is used as the first heading and it is centered and in title case. An example of formatting with this heading is as follow: Running head: SAMPLE PAPER 1 Sample Paper [paper title] Brenda Bright [author] Family of Origin Systems [class] Antioch University Seattle [institution name] Pamela Professor, Ph.D. [instructor] September 25, 2012 [full date] SAMPLE PAPER 2 Sample Paper All academic papers have a separate cover page. See the cover page of the main document as well as this Sample Paper. Because APA's (2010) Publication Manual is primarily concerned with the publication of manuscripts, this resource provides little guidance on formatting cover sheets for academic papers. David's and Blake's (2013) Style Guidelines for Writing Academic Papers, however, addresses this issue and recommend that the covers of academic papers consists of the following information: paper title, author, class, university, instructor (with academic credentials), and date submitted. These items are placed in consecutive order and in double-spaced format in the upper center section of the page. Beginning with the cover page, all pages use the “running head” format, formatted via software Header tools. The running head is placed on the left margin and the pagination indicators are placed on the right margin. The Running head format gives consistent information on all pages as is indicated in the upper left margin of this Sample Paper. Note that that the designation of the words “Running head” on the cover page is omitted from the rest of the pages and that just the abbreviated title is used for the rest of the document. The main text of an academic paper begins on the page following the cover page. The beginning of the text opens on the top line of the page, once again giving the title of the paper (but not in bold style). The introductory section does not carry a heading labeling it as an introduction because the first section of an academic paper is assumed to be an introduction. These introductory remarks present the specific topic or topics SAMPLE PAPER 3 discussed in the paper as well as present general orienting information about the intention and purpose of the paper. First Heading Describing Topic Area After the introduction, appropriate headings should then be used throughout the paper to distinguish various topic areas being discussed. Headings typically consist of one to three key words that define the topic areas. Headings orient the reader to the content of the paper via an organizational outline. In academic papers, heading are based on the criteria for the assignment and allow the instructor to confirm that the student writers cover all assignment criteria. Headings are never designated with numbers or letters. Depending on the heading level setup, headings comprise a combination of centered/flush left and bold and italic styles (see Appendix B). Paragraph Formatting In the text of the paper, all paragraphs should be indented; that is, the first line of every paragraph should be indented five spaces from the margin. After the first line, the remaining lines of the paragraph should be typed to a uniform left-hand margin with the right-hand margin left uneven. Uniform spacing. Use the ruler bar tabs to set up the paragraph indentation; once set up, the ruler bar automatically indents all paragraphs. Single sentence paragraphs. Single sentence paragraphs are too abrupt; a paragraph is composed of at least two sentences. However, also avoid long paragraphs that tend to lose readers’ attention. A paragraph longer than one double-spaced page is usually too long. SAMPLE PAPER 4 Run-on sentences. Sentences that encompass too much information also lose readers’ attention. A complete sentence usually addresses only one thought, concept, or idea; related sentences can be connected yet separated via a semi-colon (as in this sentence). Incomplete sentences. In contrast to creative writing, all sentences in academic papers must include a subject and a verb. The creative use of dependent clauses as sentences does not meet academic standards for graduate writing. Subject-verb agreement. A singular noun or subject requires a singular verb; conversely, plural nouns or subjects require a plural verb. Noun-pronoun agreement. Nouns and pronouns must also agree regarding being singular or plural. The students diligently wrote their papers. The first-quarter student diligently wrote her paper. Conclusion A concluding paragraph is typically written at the end of an academic paper (with the heading designated in bold style). A conclusion section concisely summarizes the points made in the paper as well as offers the writer’s final subjective perspective about the themes addressed in the paper. References Academic papers end with a separate reference page called the Reference list. Do not use bold style for this heading as indicated on the top of page six of this Sample paper. The References list alphabetically delineates all the sources cited in an academic paper. The References list cites only those sources mentioned in the paper and should not be confused with a bibliography which cites works for background or for further reading. SAMPLE PAPER 5 The “personal communication” citation appears only in the body/text of the paper and does not appear on the References list. Guidelines for formatting the References page are provided in this document. SAMPLE PAPER 6 References American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. David, P., & Blake, A. B. (2013, Winter Quarter). Style guidelines for writing academic papers. Handout from the School of Applied Psychology, Counseling, and Family Therapy. Antioch University Seattle.