Association between smoking and tuberculosis infection: a

advertisement

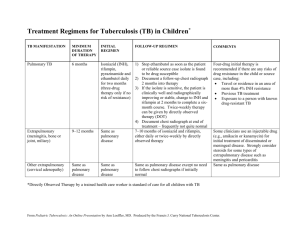

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN PULMONARY TUBERCULOSIS AND SMOKING : A CASE CONTROL STUDY Talha Saad 1, Jyoti Markam 2 1.Department of Respiratory Medicine ,Bundelkhand Medical College,Sagar, Madhya Pardesh 2.Department of Community Medicine , Bundelkhand Medical College,Sagar, Madhya Pardesh Abstract Background: Tuberculosis (TB) is a key public health problem among population of Sagar district in Madhya Pradesh state, central India. However, there is no any detailed study undertaken to find out the risk factors associated with the development of TB disease in this community. A case controlled study was conducted among population in Sagar district of Madhya Pradesh to find out association with smoking and tuberculosis. Methods : A total of 111 sputum smear positive patients of pulmonary tuberculosis and 333 controls matched for age and sex were interviewed according to a predesigned questionnaires . Results: The adjusted odd ratio of the association between tobacco smoking and pulmonary tuberculosis was 3.8 (95% CI 2.0 to 7.0 p value < .0001). A positive relationship between pack year, BMI and socioeconomic class was also observed. Conclusion: The study has demonstrated strong association between smoking and tuberculosis. We need to supplement the efforts in advocacy, communication and social mobilization for reducing the smoking in the community for effective control of Tuberculosis. Address for corrospondence: Dr Talha Saad Department of Respiratory Medicine, Bundelkhand Medical College,Sagar,MP,470001 dr.talhasaad@gmail.com Introduction India is classified along with the sub-Saharan African countries to be among those with a high burden and the least prospects of a favourable time trend of the disease as of now (Group IVcountries). The average prevalence of all forms of tuberculosis in India is estimated to be 5.05 per thousand, prevalence of smear-positive cases 2.27 per thousand and average annual incidence of smear-positive cases at 84 per 1,00,000 annually. (1). The World Health Organization has set a goal to lower annual TB incidence to less than one case per million by 2050 (1). Although the current approach to TB control focuses on case detection and treatment, recent studies suggest that this strategy might not be sufficient to achieve this goal and it may also be necessary to reduce risk factors that contribute to the occurrence of tuberculosis infection and/or disease (2, 3). Such risk factors may act at one of several steps in the natural history of the disease. Susceptible individuals become infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis after exposure to a person with active pulmonary tuberculosis. Once infected, individuals either develop disease within the first 1 to 2 years of infection, referred to as primary disease, or go on to develop a latent asymptomatic infection, which can progress to active disease sometime during that individual’s life. A first step toward this goal is to better understand the effects of modifiable risk factors, including tobacco smoking, on any of these steps that could ultimately increase the occurrence of TB. An estimated 1.3 billion people smoke tobacco products, the majority of whom live in low- or middle-income countries where the burden of TB is also concentrated (4). Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies have pointed to a positive association between tobacco smoking and active TB disease (5-7). Several large observational studies also reported an increased mortality from TB among smokers but these studies did not provide direct evidence on smoking and the incidence of active TB (8-10).A few cohort studies have reported a positive association between smoking and active TB (11-14). However, these cohort studies might not have yielded generalized results because they were conducted in highrisk populations such as gold miners (11), patients with silicosis (12,13), and the elderly (14). We report here a population survey conducted in Sagar District, Madhya Pradesh that provides evidence that smoking may increase the risk of tuberculosis . We did one year epidemiological research in the study population. METHOD AND MATERIAL:- Case control study was conducted at Sagar district , Madhya Pradesh India. All the pulmonary tuberculosis cases registered in Outpatient of Bundelkhand Medical College Sagar ( n=165). The controls (n=333) were subjects without respiratory disease. All controls were subjected to clinical evaluation, chest radiograph and sputum examination. All subjects with co morbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus, human deficiency virus infection, malignancy and those on any immunosuppressive drugs were also excluded from study. The total number of registered cases in the Outpatient were 165. In this study 125 cases were completely approachable and rest of cases 40 are not found due to incomplete addresses , wrong addresses, migrate from city or death of patient. Out of 125 cases only 111 cases agree for interview and rest of 14 cases not given consent for interview. Matching factors was age ± 5 years , sex and socioeconomic status. In person interview of each case and control was taken using a pretested structured questionnaire enquiring about smoking history, household smoke exposure , environmental smoke exposure , tobacco chewing ,alcoholism, housing characteristics and score on modified Prasad socioecomonic status scale was used for data collection. This scale takes account of per capita income of the family to classify study groups into Upper high ,High, Upper middle, Lower middle,and Poor socioeconomic status. Detail of smoking were noted carefully with regard to type , current smoking status, age of starting smoking , duration of smoking , quantity of smoking. In this study somking was defined as having ever smoked for at least 5 years. The number of pack year smoked was calculated as the average number of bidi smoked per day multiplied by the duration of smoking divided by 20. Result:A total of 111 patients and 333 controls were enrolled in the study. Smoking history was present in 33.3% of patients as compared to 13.8% of controls. The mean pack /year were 4.77 among patient and 0.88 among controls. The odd ratio of developing pulmonary tuberculosis among smoker was 3.8 times more than that nonsmokers [ odd ratio =3.8 (95%CI 2.0 to 7.0) p<0.001] The odd ratio of developing pulmonary tuberculosis among person who smoked for a duration of >5 years [ adjusted odd ratio= 5.7 [95% CI 2.4 to 13.1] was more in comparison to person who smoked for a duration of <5years [ adjusted odd ratio= 2.5 [95% CI 1.1 to 5.7] Analysis were also done to assess the association between pulmonary tuberculosis and various factors like socioeconomic status, BMI, type of housing and alcohol intake. The odds of developing pulmonary tuberculosis among social class V [ adjusted odd ratio =5.3( 95% CI 1.8 to 16.0]was more than that among social class IV [ adjusted odd ratio= 2.3 (95% CI 0.8 to 6.7] with reference to social class type III. Alcohol intake was also found to have an association with the occurrence of pulmonary tuberculosis [adjusted odd ratio=1.7( 95% CI 0.9 to 3.3)] BMI < the median valve of 19.4 was strongly associated with pulmonary tuberculosis[ adjusted odd ratio =4.1( 95% CI 2.5 to 6.8)] Person living in kuccha or semipukka houses [ adjusted odd ratio=3.2[ 95%1.4 to 7.5)] had almost similar odds of developing pulmonary tuberculosis when compared with person living in pucca houses [ adjusted odd ratio =2.3 (95% CI 1.6 to 5.6)]. Table 1: Association of pulmonary tuberculosis and smoking variables cases controls matched (111) (333) odd ratio (95% CI) adjusted odd ratio (95% CI) p value Duration of smoking <5 years 15 (13.5) 30 (9.0) 2.0(1.0 to 4.2) 2.5(1.1 to5.7) 0.03 >5 years 22 (19.8) 16 (4.8) 5.6(2.7 to 11.8) 5.7(2.4 to 13.1) 0.0001 Table 2: Factors associated with pulmonary tuberculosis Variables Matched OR (95% CI) Adjusted OR (95% CI) p value >45 2.56(1.84-3.56) 2.51(1.81-3.50) <0.0001 <45 1.28(0.87-1.89) 1.21(0.77-1.86) <0.0001 Smoking 3.4 (2.0 to 5.8) 3.8 (2.0- 7.0) <0.0001 5.3 (1.8 to 16.0) 2.3(0.8 to 6.7) 3.6(1.0 to 12.8) 1.9 (0.6 to 6.4) 0.04 0.3 3.2 (1.4 to 7.5) 2.8(1.1 to 7.2) 0.03 semipucca Body mass index 2.3 (1.0 to 5.1) 4.1(2.5 to 6.8) 2.3(0.9 to5.6) 4.2(2.4 to 7.3) 0.07 <0.0001 Alcohol 19(17.1) 37(11.1) <0.0001 Age Social class type V type IV House type kuccha DISCUSSION This study shows that current or ex-smokers had a higher prevalence of TB than never smokers and that there was a slightly higher risk for age >45 years.This suggests that the increased risk of disease and death from tuberculosis among smokers may be due, at least in part, to an increased risk of smokers becoming infected with M tuberculosis. Our study confirms previous studies that showed an association between smoking and tuberculosis infection in at risk groups(11-14) For example, in silicotic patient(12-13) reported a higher risk of infection among smokers which increased with duration of smoking. In contrast to previous studies investigating specific high risk groups,(11-14) the current study is the first to investigate the correlation between smoking and tuberculosis in a cross sectional population survey in a high incidence community. The reason for the increased risk of infection in smokers is unclear, but may be explained by the effects of smoking on pulmonary host defences. Smoking has been shown to reduce natural killer cytotoxic activity, to suppress T cell function in both lung and blood, to impair mucociliary clearance of particles, and to increase numbers of alveolar macrophages in the lower respiratory tract. Cells of the macrophage-phagocytic group influence immediate or innate immunity through their handling and elimination of mycobacteria, and products of cigarette smoke may therefore favour persistence and/or replication of ingested mycobacteria by impairing the macrophage or dendritic cell function. (15) To take possible sources of bias into account we have considered the following. Men and persons in the highest income category are under-represented, but this is unlikely to be of significance as neither sex nor income was a confounder for the association between smoking and positive sputum for AFB. A weakness of the study is that we did not test the HIV status of participants and were therefore not able to correct for HIV status. Confounding factors that were taken into consideration were individual monthly income, BMI, and education level. However, we cannot entirely discount the possibility that socioeconomic and behavioural differences other than smoking may have affected the relationship between smoking and tuberculous . Although our evidence suggests that tobacco smoking is only a moderate risk factor in TB, the implication for health in this rural population is critical. Because tobacco smoking is quite prevalent, a considerable portion of TB may be attributed to tobacco smoking . More importantly, this association implies that smoking cessation might provide benefits for TB control in this rural population. There is an urgent need to develop and implement culturally appropriate awareness raising activities to target smoking to support the efforts to control TB in this community. REFERENCES 1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: epidemiology,strategy, financing: WHO report 2009 (who/htm/tb/2009.411). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009 2. Dye C, Williams BG. Eliminating human tuberculosis in the twenty-first century. J R Soc Interface 2008;5:653-662. 3. Lonnroth K, Raviglione M. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis: prospects for control. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2008;29:481-491. 4. Shafey O, Dolwick S, Guindon GE, editors. tobacco control country profiles (2nd edition). Atlanta: American Cancer Society, World Healt Organization, International Union against Cancer; 2003. 5. Bates MN, Khalakdina A, Pai M, Chang L, Lessa F, Smith KR. Risk of tuberculosis from exposure to tobacco smoke: a systematic review andmetaanalysis. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:335-342. 6. Slama K, Chiang CY, Enarson DA, Hassmiller K, Fanning A, Gupta P,Ray C. Tobacco and tuberculosis: a qualitative systematic review andmeta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007;11:1049-1061. 7. Lin HH, Ezzati M, Murray M. Tobacco smoke, indoor air pollution and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2007;4:e20. 8.Gajalakshmi V, Peto R, Kanaka TS, Jha P. Smoking and mortality from tuberculosis and other diseases in India: retrospective study of 43000 adult male deaths and 35000 controls. Lancet 2003;362:507-515. 9.. Gupta PC, Pednekar MS, Parkin DM, Sankaranarayanan R. Tobacco associated mortality in Mumbai (Bombay) India. Results of the Bombay Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:1395-1402. 10. Liu BQ, Peto R, Chen ZM, Boreham J, Wu YP, Li JY, Campbell TC, Chen JS. Emerging tobacco hazards in China: 1. retrospective pro-portional mortality study of one million deaths. BMJ 1998;317:1411-1422. 11. Hnizdo E, Murray J. Risk of pulmonary tuberculosis relative to silicosis and exposure to silica dust in South African gold miners. Occup Environ Med 1998;55:496-502. 12. Chang KC, Leung CC, Tam CM. Tuberculosis risk factors in a silicotic cohort in Hong Kong. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2001;5:177-184. 13. Leung CC, Yew WW, Law WS, Tam CM, Leung M, Chung YW, Cheung KW, Chan KW, Fu F. Smoking and tuberculosis among silicotic patients. Eur Respir J 2007;29:745-750. 14. Leung CC, Li T, Lam TH, Yew WW, Law WS, Tam CM, Chan WM, Chan CK, Ho KS, Chang KC. Smoking and tuberculosis among the elderly in Hong Kong. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:1027-1033. 15.Sopori M. Effects of cigarette smoke on the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol2002;2:372–7