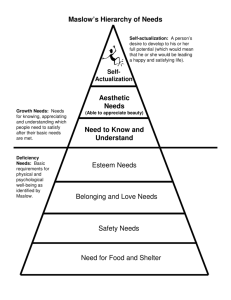

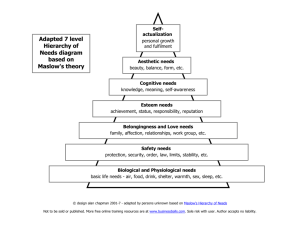

Maslow's Hierarchy

advertisement

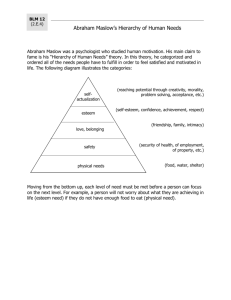

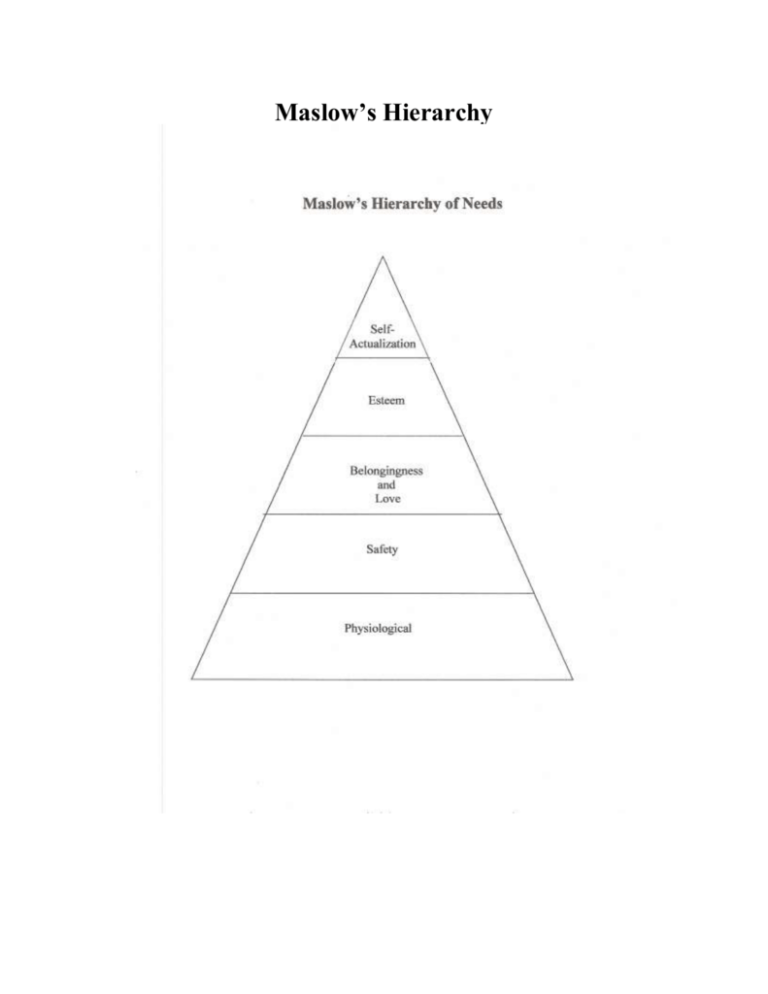

Maslow’s Hierarchy The lowest level of the pyramid, Physiological, comprises basic survival needs: air, food, water, and shelter. When physiological needs are fairly well addressed, then, in Maslow’s model, the individual turns to Safety needs. At the Safety stage, one tends to look for safety and experiences that are directly related to safety, such as stability (“Today I can look forward to the same people helping me as yesterday”), protection (“Today, I have a reasonable expectation that no one is going to take my wristwatch or my dentures, or hit me, or leave me in my own urine”), and order (“Today, I know that my daughter will visit me”) so that the individual’s environment becomes more predictable. Once safety needs are addressed, a person tends to look for someone to be with - a group to which to belong. One may define oneself as a teacher, electrician, doctor, or as belonging to a trade or profession. This is the Belongingness and Love stage. Once Belongingness and Love needs are met, one begins to fill Esteem needs. Based on his observations, Maslow concluded that there are lower and higher esteem needs. Lower esteem needs include wanting to have the respect of others, status, recognition, attention, and reputation. Higher esteem needs include self-respect, confidence, mastery and independence. Maslow clustered the first four needs as “Deficit Needs.” If one has a deficit in any of these areas, one experiences that area as a need. For example, if my family leaves me without warning, then I will put a great deal of emotional energy on fulfilling my need to belong. If I’ve given 25 years of my life to a company that goes bankrupt leaving me with no retirement, besides and after being overwhelmed and grieving over my loss, I will focus on earning money. Maslow understood mental disorder as reliving the experience of loss or trauma that one had in an earlier stage of development and fixating on that. For example, if I grew up during the Great Depression, even though I am a success, I might be preoccupied with financial security, hiding money under mattresses, etc. The fifth level, the highest level of need in Maslow’s model, he characterized as being needs, or Self-Actualization. Maslow found that people who were self-actualized tended to be problem solvers, not problem receivers. They tend to place a great deal of emphasis on primary relationships: family, long term friendships. Most important, they tend to have a distance from social and physical needs. When Elisabeth Kubler-Ross did her work on death and dying, these were the individuals who would tend to respond to news that they were terminally ill with a quiet acceptance, and a determination to live their life each day, beginning that day – in other words, straight to resolution without intermediate stages of denial, depression, anger, and bribery. Sense of Purpose This "tree" represents a person. Please note that adaptability is greater or lesser depending on one's competence: physical, psychological, emotional, economic, social, spiritual. The more competent the individual the greater the individual may withstand the pressures from the external environment. What also makes the difference is the degree to which an individual may adapt is his or her roots. This is the degree to which an individual meets his/her personal needs, per Maslow's framework, but also, most importantly, one's sense of purpose. Now, that sense of purpose may come from a philosophical, spiritual or a religious basis, but it may also come from one's sense of obligation to others. The sense of purpose is the main root, the taproot of the human being. If the sense of purpose is strong, it serves as an anchor that grounds the individual so strongly that even in the face of loss of everything, somehow, everything is not everything. There is always something there, some purpose. Grief Grieving is a very interesting area for consideration. The first work in grief reaction was done by Eric Lindemann, who studied the aftermath of the Coconut Grove fire. The Coconut Grove was a popular nightclub in Boston. On November 28, 1942, a fire resulted in the deaths of 493 people. At that time, the Coconut Grove fire was the worst single building fire in the nation’s history. Lindemann studied the reactions of survivors and family members of those who had died. The result of his survey was that there were four stages of grief (denial, depression, anger, and resolution) and that most people “recover” within a finite period of time. Some years later, Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross did her work on death and dying and she found that for the dying there were five stages of grieving: denial, depression, bribery, anger, and resolution. Dr. Kubler-Ross also found that some people (individuals with a sense of purpose in their lives) didn’t go through stages, but immediately went to resolution. Subsequent work in grieving has led to the following conclusions (summarized by Jeffreys, J.S. (2005). Helping Grieving People – When Tears are not Enough NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.) Grief is unique to each individual. There may be one stage, or 14 or 76. Grief is really the individual’s adaptation to loss. We say that people “move on.” Grieving does change the individual, because it forces one to form a different internal image. The grieving process itself is the way the individual – body, mind and spirit – adapts to loss. It’s the individual’s way of healing and moving on. Sometimes the grieving process is simple, consisting of just the reaction to the acute loss. Sometimes, grieving becomes complex, such as when it’s added to already strained relationships, or when it’s added to the pre-existing distorted thinking, feeling, and behavior of an individual. Grieving is a normal response to a loss, whether the loss is of an individual through death, or the loss of a body part. So it is not something that needs to be fixed. It’s as inappropriate for an individual to say to someone who is grieving, “Get over it,” as it would be to say those words to someone with diabetes. Grief is not a disease. It’s a normal part of living.