proposed malaysia-united states free trade agreement (mufta)

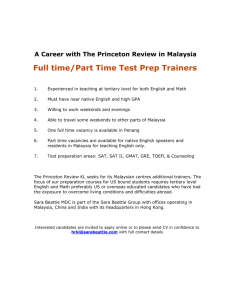

advertisement