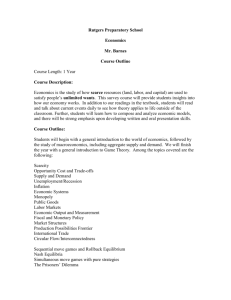

Syllabus - The Unbroken Window

advertisement

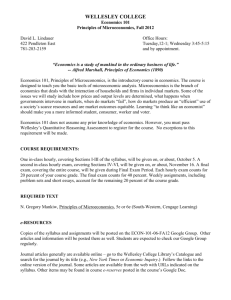

Spring 2006 Syllabus Course Information Course: Economics 110 – Introduction to Economics (Economics for the Citizen and for the Aspiring Economist) Meetings: Section A: Mon., Wed., Fri. 11:30am - 12:30pm (Young 101) Section B: Mon., Wed., Fri. 1:50pm - 2:50pm (Crounse 313) Course Web Page: http://web.centre.edu/rizzo/ (click on “Teaching” in main menu on top of page) Please get into the habit of accessing the web page regularly. Most of your readings will be available right from the course page. I use the webpage to keep the class abreast of current events in economics and I also use it to make administrative announcements and reminders in the event you didn’t write them down in class. Instructor Information Instructor: Michael Rizzo Office Hours: (Official Hours) Monday, Wednesday, Friday 3:00pm – 4:30pm; or by appointment. Office Location: Office Phone: E-mail: 417 Crounse 238-5239 rizzo@centre.edu Home Phone: 236-5656 (I am more than happy to chat with you from home if you need me. Please try not to call after 10:00pm. I urge you to leave a message if I do not answer, I am often found with my hands full and neglect to charge after a ringing phone due to concerns for my own, my wife’s, our animals’ and our child’s safety! Course Description Each year thousands of students study economics. The work of millions of writers, politicians, pundits and educators requires a basic proficiency in the fundamentals of economic analysis. Sadly, few have been able to demonstrate such competence. A quick note of some recent quotations will demonstrate this quickly: “I have a plan for energy independence within 10 years...we're going to free ourselves from this dependency on Mideast oil”, “Hurricanes Boost Florida Economy”, “We are running out of (insert resource name here)”, “The market is only creating bad jobs”, “Boycotting the products produced by sweatshop laborers will teach (company name) a lesson”, “Farm to Cafeteria … makes good economic sense”, etc. Economics is about the everyday world around us. The study of economics is intended to equip you with a set of tools to analyze the difficult decisions faced by individuals, firms and governments – it is a theory of choice and its unintended consequences. In other words, the goal of this course is to introduce you to a way of thinking, not simply to show you a set of principles that are an ends unto themselves. The goal of this course is to enable you to analyze economic policies logically, and in a way that you can illuminate an issue rather than rabble-rouse it. The goal is to enable you to take positions of public affairs based on facts, knowledge and intelligent analysis of the consequences of policy proposals. 1 Spring 2006 Syllabus These goals will be achieved through a careful study of economic theory mixed with a substantial dose of real-world application. We will frequently visit common myths and misperceptions about economics and understand why they have evolved, what the error in thinking is and how to move the debate forward. The first ¾ of the course will focus on microeconomics – or the study of the choices and constraints faced by individual decision making units. Example of questions to be answered include: why support for the minimum wage is much stronger among politicians than economists; when should a business decide to open or shut down; why do diamonds cost so much more than water if water is necessary for human survival? The last ¼ of the course will introduce you to macroeconomic analysis – that studies the consequences of microeconomic decisions on national income, national employment levels, the overall price level in an economy, how government actions affect the economy and how the Federal Reserve Bank impacts the economy. While the course will not rely on as heavy a dose of graphics and algebra as one might expect from an economic theory course, it will still nonetheless be an important tool to help illustrate difficult economic concepts. I urge each of you to study the appendix to Chapter 2 for a review of basic graphing, algebraic and analytic tools that are important. The course will combine a combination of traditional lectures, classroom experiments, videos clips and discussions (or debates). Finally, I’d like for you to understand that the study of economics is not an attempt to design the world around us – it is far too complex a task. Rather, it is intended to have you appreciate this marvelous complexity. In addition, the study of economics would be hollow if not supplemented with a solid appreciation of philosophy, psychology, hard science, literature, culture, language and more. This is why the study of economics at a liberal arts college is so important. It would be productive to learn that nearly all of the “original” economists that you might have heard of were actually Moral Philosophers. In fact, Adam Smith, best known as the “Father of Modern Economics” and for writing “The Wealth of Nations” in 1776, actually wrote a classic, “The Theory of Moral Sentiments” in 1759. The “Wealth of Nations” cannot be treated as a separate work from it, but rather as an extension of it. The essence of the two is that free-markets and a global economy work only when a majority of citizens have a concern for justice and the cultivation of virtue. That these essentials are often overlooked by critics of the market system and Smith himself has led to widespread misunderstanding of economics. Course Materials and Resources There are two required books for the course and one additional recommended selection. The course readings will come from the required books and there will be an optional paper / extra credit assigned from the recommended selection. 1. The text is by N. Gregory Mankiw and is called Essentials of Economics (3rd edition). This is an excellent introductory level textbook and whether I cover the material directly or not it will be an excellent resource for you. The textbook is fairly expensive. The bookstore is selling it new for $133.50 and used for $100.25. With the purchase of the book, you will have access to an outstanding support website for the book. It really is an excellent practice and study guide. With purchase, you will also have access to an e-Book for a larger book called “Principles of Economics” that contains all of the chapters in our Essentials book. 2. The second required book is called The Undercover Economist by Tim Harford. This will be read in conjunction with several of the text chapters. I am positive you will find this more accessible and interesting than the text. Among other things Tim Harford writes the “Dear Economist” column for the Financial Times. The book is selling for $26.00 new and $19.50 used in the bookstore. 2 Spring 2006 Syllabus 3. The recommended, but not required, book is the 50th anniversary edition of The Road to Serfdom, by 1974 Nobel Prize winning economist Friedrich August von Hayek. The Adam Smith Institute describes the book as such: For over half a century, it has inspired politicians and thinkers around the world, and has had a crucial impact on our political and cultural history. Hayek argues that, while socialist ideals may be tempting, they cannot be accomplished except by means that few would approve of. Addressing economics, fascism, history, socialism and the Holocaust, Hayek unwraps the trappings of socialist ideology. He reveals to the world that little can result from such ideas except oppression and tyranny. Today, more than 50 years on, Hayek's warnings are just as valid as when "The Road to Serfdom" was first published. This book is really the precursor of a longer line of more theoretically well developed and disciplined approaches to the topic of central planning. You will be offered the option of writing a paper on this book and there may be other extra credit opportunities based on your insights from its reading as well. The book sells at the campus bookstore for $14.00 new and $10.50 used. During the course of the semester I will periodically assign articles and papers to read that have not yet been listed on the syllabus. In all cases, you will have access to PDF or other online formats on the course web page in order for you to be able to access the readings anywhere a computer is available. Class Policies 1. Attendance – missed classes We are all adults and I will treat you as such. While attendance is not mandatory, I would obviously prefer it if you came to each session as I believe the material is easier to digest the more times you get to see it. I have been known to call students up to see how they are feeling when they do not show up for class. Further, the registrar asks that I submit an attendance sheet to him at the end of the semester. While attendance will not be directly factored into your grade for the course, I will be evaluating you on things that happen inside the classroom, which can obviously not be “made up” when a class is missed. 2. Attendance – late for class Class time is limited and students entering class late provide a distraction for both fellow students and the instructor. Students arriving late for class will therefore suffer a penalty of 1/3 of a grade on the most recent homework or writing assignment score for each day you show up late for class. It’s not OK to show up late for a job and it will not be OK to show up late for a class either. 3. Missed Classes for College Sponsored Events You will be excused from the regular term equivalent of THREE classes during the course of the term if I receive notification that you have an obligation to attend another college sponsored event (e.g. performance, athletic event, field trip, etc.). Though these missed classes will not count against your grade, I do expect you to get notes and any missed assignments from your classmates. If you let me know early enough in the semester when you will be away, I may be able to get assignments and other materials to you earlier. 4. Rescheduling Assignments If the timing of a certain assignment is extraordinarily difficult for you to satisfy, please see me BEFORE the assignment is due so that we can work out a solution together. When I say 3 Spring 2006 Syllabus BEFORE, I do not mean midnight on the evening it is due, but three or more days advance notice is sufficient. 5. Late Work Unanticipated late work will not be accepted and will receive a grade of zero. This policy is in effect in order to be fair to those students that do complete their work on time. Once again, late work on a job is not acceptable, nor is it acceptable in this class. Of course, students with medical or other emergencies will not be penalized if a note from Health Services or Student Support Services has been provided to me. 6. Please be Respectful of your Fellow Classmates Please turn off all cell phones, beepers, etc. during class. If a phone or beeper as much as vibrates during class, I will enjoy speaking with the person that calls you to let them know you are in the middle of class. If the problem persists, I will enjoy the use of that device until the next time class meets - which will include me answering all calls on your behalf during that time! Please present yourself neatly in class and be prepared to share any snacks or meals with your classmates. Of course, feel free to bring water with you. 7. Students with Special Needs If you need special accommodation for classes and / or assignments, please see me BEFORE the assignment is due or class meets so we can work out something that will make you comfortable. You must also see Mary Gulley or Ann Young in order to receive the proper documentation. I am unable to help you out without this documentation finding its way to me first. New policy at Centre requires that you meet with me so that I can sign the laminated form that you will receive from the Assistant Dean. 8. Feedback I urge each of you to provide me with feedback throughout the term. You may simply e-mail me or see me or place a note in my mailbox or under my office door (anonymously if you like). I have also placed a lecture evaluation link on the course website if you prefer your critique be publicly viewable. Course Requirements I have randomly assigned you into working groups for the course. These groups will be very important so I urge you to get familiar with your fellow classmates and get all of the appropriate contact information from them that you will need to successfully work together for 14 weeks. The groups will be used for two purposes. First, I will allow each of the groups to turn in common problem sets. I will assign problem sets throughout the term which are to be submitted by your group as a single problem set. Second, there may be opportunities inside and outside of class when working in a group will be helpful. The groups are: Section A – 11:30am Class Group 1: Bentley, Kris; Eggers, Ashley; Griffin, Morgan; Pilkington, Taylor Group 2: Brickman, Trevor; Dove, Jillian; Ezell, Chase; Gray, Taylor Group 3: Banks, Hannah; Henry, Michael; Jozwiak, Barbara; Koeninger, Kelly Group 4: Akridge, Matt; Beard, Stephanie; Menard, Erin; Placido, Andy 4 Spring 2006 Syllabus Group 5: Ames, Phillip; Atha, Chris; Coffey, Kathleen; Garrett, Wilson; Miller, Sarah Group 6: Boggan, Josh; Campbell, Leah; Dean, Landon; Evans, Josh Group 7: Allen, Catherine; Gash, Alex; Griffith, Tyler; Murphy, Erin; Ottley, Jonah Section B – 1:50pm Class Group 8: Chadwick, Jason; Schatz, Jessie; Steinmetz, Kevin; Ubelhart, Alex Group 9: Allen, Kendall; Dahlman, Rachael; ido, Andy; Restrepo, Cassie Group 10: Arave, Erica; Herrick, Chris; Lopp, Christine; Zimmerman, Chris Group 11: Bouvier, Katie; Davies, Dan; Greer, Andy; Link, Ethan Group 12: Braden, Beau; Droste, Jessica; Keller, Amanda; Mullins, Elijah; Rodes, Nelson Group 13: Brooks, Zach; Cotterell, Sarah; Foote, Tyler; Stevens, Joshua Group 14: Allison, Drew; Calitri, Chris; Chaffin, Jesse; Saneii, Sarah; Schuhmann, Laura A. Examinations (70% of course grade) You will have three examinations during this course. Each of the two midterm exams will count as 17.5% of the course grade. The final exam will count as 35% of the course grade. The first midterm will be in-class on Friday, March 10th. The second midterm will be in-class on Friday, April 14th (this is Good Friday, so I may change the date of this exam). The final examination will count as 35% of your course grade and will be a three-hour written examination. For Section A, the exam is scheduled for Wednesday, May 17th from 8:30-11:30 in Young 101. For Section B, the exam is scheduled for Tuesday, May 16th from 1:30-4:30 in Crounse 313. There will be NO MAKEUP examinations offered. An unannounced missed exam will result in a grade of U. If you are excused from an examination, your final and remaining midterm examinations will make up larger portions of your course grade. B. Problem Sets and Writing Assignments (30% of course grade) There will be several problem sets and writing projects assigned throughout the term. The problem sets are to be completed with your group while the writing assignments are to be completed individually. 1. Problem Sets: There will be at least four problem sets assigned designed to help you prepare for the exams and to think about the text and class materials in a different way. These assignments are meant to be truly cooperative. In other words, each of you is supposed to work the entire problem set on your own. Then the group is to get together to discuss each question and answer and construct a best answer. The group is to turn in one problem set for the group and then provide evidence that each individual worked the problem sets and contributed to the group discussion. Part of the grading of these problem sets will be a function of your fellow group members evaluation of your work at the end of the year. 2. Writing Assignments: There will be semi-regular writing assignments throughout the term. These will be handed out in class. All of the writing assignments are to be completed individually. Examples of these assignments include identifying signs of 5 Spring 2006 Syllabus economic illiteracy in the press or other external sources (e.g. in a conversation you had over lunch, etc.) or providing insights into interesting economic questions of the day (e.g. where does competition come from?). C. Paper on The Road to Serfdom (optional / discretionary). You have the option of writing a 2,000 to 3,000 word essay (described below) on F.A. Hayek’s classic work. If you choose to write the paper, you can have the paper take the place of one of the two midterm exams or you may have the paper count for extra credit. If you choose the later option, I’ll count it for 20% of your final grade and reduce the remainder of the course weights proportionally if the paper grade exceeds your remaining course average. If the paper grade does not exceed the remaining course average, I may use it purely on an extra credit basis to adjust your final grade upward. Of course, you are not obligated to write this paper. Intrepid students that choose to undertake this project with seriousness of purpose may elect to write a version of no longer than 6,000 words and may have it take the place of the final exam. The paper is composed of two pieces. The first is observational. I’d like you to identify and briefly describe four major critiques levied against socialism in the book. Rather than address the atrocities of “Hot Socialism” as Hayek describes it (e.g. the brutal situation that prevails in North Korea and that prevailed under Mao, Stalin and others, but is largely extinct today), address these critiques while assuming that “socialists” are well intentioned. The second piece of the paper is analytical. Using what you have written in the first part of the paper, and from your observations of the world today and what you are learning in other courses, analyze whether Hayek’s critiques are as effective against the “statist” attacks on markets and freedom as they are against the socialist attacks on markets and freedom. For those wishing to write the longer paper, you should include a third section. First, I’d like you to read and reproduce Article I, Section 8 of U.S. Constitution. It stipulates exactly 18 powers that the national legislature is allowed to exercise. If Congress goes at all beyond those 18 powers, they are in “violation of law”. After considering this section, comment on what government activities in the 21st century U.S. seem to violate this section. From this, assess whether we are experiencing “creeping socialism” (as Hayek describes it) today in the U.S. Finally, I’d like for you to tie the lessons of the paper in with the lessons from this course to answer: Can the modern welfare state really create social justice? How does it produce “more just” outcomes than those which are produced by the market (as if “the market” actually produces anything)? Are the critiques levied against “the market” really a criticism of something inherent in capitalist systems, or is it something else? (Consider that as strange as it sounds Marxists and classical liberals actually agree on many things – particularly as it pertains to exploitation theories – it’s just that the source of the critiques differs between these two schools) To help you start thinking about the paper, I’ve excerpted comments from a talk given by Virginia Postrel in 1999 below. For the full version of the talk, see here: http://reason.com/9911/fe.vp.after.shtml. The goal of socialism is a fairer allocation of economic resources, which its advocates often claim will also be a less wasteful one. Socialism is about who gets the goods and how. Socialism objects to markets because markets allocate resources in ways socialists believe to be unfair on both counts: both the who and the how. We must keep in mind what socialism is, and therefore what it is not. Socialism, creeping or galloping, is an ideological concept with a particular sense of what is important. What 6 Spring 2006 Syllabus distinguishes socialism is its appeal to economic fairness. It declares that markets do not allocate wealth and power fairly, and that political processes will do a better job. Socialism is not simply about moving money from the powerless to the powerful--a goal as old as politics--but about flattening the distribution of income and wealth. Pork-barrel spending is not socialism. Farm subsidies are not socialism. "Corporate welfare" is not socialism. These programs are not ideological in nature. They are about competing interest groups. The statist attack can be summed up simply by people being uncomfortable when “no one is at the controls” of complicated processes. These attacks being: First, it argues that we should not let people take chances on new ideas that might have negative consequences and second, is the argument against externalities … Most of us have been willing to grant the problem of externalities in such areas as air pollution and to look for ways of addressing it with minimal disruption of market processes. But it's not that hard to declare that every market action has potentially negative spillover effects. The infinitely elastic version of the externality argument turns the language of market-oriented economics against the essential nature of commerce. Indeed, we increasingly see the externality argument aimed not at producers, the traditional target, but at consumers. My choice of which movies to watch creates cultural pollution. My purchase of convenient packaging produces environmental waste. My house color or garage facade does not please the neighbors. My purchase of consumer goods leads to "luxury fever" that hurts everyone. We are all connected in the marketplace, and therefore, in this view, our actions must be tightly regulated to contain spillovers. What's the single most important thing to learn from an economics course today? What I tried to leave my students with is the view that the invisible hand is more powerful than the hidden hand. Things will happen in well-organized efforts without direction, controls, plans. That's the consensus among economists. That's the Hayek legacy. D. Course Contributions and Classroom Productivity (my discretion) This is not simply a verbal class participation requirement. A small portion of your final course grade will be a function of how well you are making use of your time outside of class. Due to the very short time span in which a large amount of the material is covered, it will be nearly impossible for you to appreciate the complexities of economics without doing all of the assigned readings and exploring in detail the many questions I will be asking. This is particularly the case given that the amount of reading you might do to introduce yourself to economics is infinite plus I do not like to follow the textbook precisely. That does not mean you are not responsible for all of that material. Your hard work and seriousness of purpose will benefit all of your classmates as it will vastly expand the number of things we can discuss and learn in class, but also enhance the depth of the debates that will take place. To the extent that you are able to raise the level of the conversations we have in class by your preparation and your asking of serious questions in class, you will be rewarded in your grades. To the extent that you demonstrate a lack of respect for your classmates and the instructor by either not preparing fully for class, by not being fully attentive in class or by not pulling your weight in completing the assignments, your course grade will be negatively affected. Grading Policy To summarize from above, your course grade will be comprised of: I. Two Midterm Exams (each worth 17.5%) II. Final Exam III. Problem Sets and Writing Assignments IV. Course contributions and productivity 7 35% 35% 25% my discretion Spring 2006 Syllabus Grades will be based on your demonstration and mastery of knowledge and skills learned throughout the formal course meetings and on your ability to think critically about and to analyze the situations you encounter outside of the classroom. Though the total of the above scores is 100% there will be ample opportunities to either improve upon or damage your grades. I will point these out as we move through the semester. You are NOT in competition with your fellow classmates for grades. Economics is NOT a zerosum game, nor is learning. I have no limits on the number of A’s I will award. At the same time, I do not have a target number of scores to award either. You will receive the grade that you earn. While effort alone is not sufficient to secure a top grade, students that demonstrate a continued effort throughout the course will have many opportunities to improve upon a poor grade. The grades will not be curved. Your total score for the course will be converted into a percentage (properly rounded). Then, I will use the following grade scale to determine your letter grade: 94% - 100% 90% - 93% 88% - 89% 83% - 87% 80% - 82% 78% - 79% 73% - 77% 70% - 72% 60% - 69% below 60% A AB+ B BC+ C CD U Regrading Policy In cases where clear grading mistakes have been made (e.g. points are added up incorrectly) please notify me immediately and I will correct them. In cases where there is a dispute over a grade, I ask that students not just “barge into my office” with a complaint. I will listen to all disputes as long as the student submits a written (or e-mailed) description to me as to why she/he feels the grade is incorrect before you come to see me. If it is clear that I have made a mistake, I will make the change. In cases where complaints are nonspecific and your submission does not address the economics of the question asked, I will not consider the request. Some other thoughts on grades: For those of you that are nostalgic about higher education, I pulled the following grading guidelines from a professor at an elite liberal arts college in the early 20th century: Students shall receive a letter grade of: A when students have excellent command of the subject matter and demonstrate an ability to apply their knowledge beyond the specificity of the course materials. Their knowledge of the subject matter includes some of the finer points of economics and may include information not specifically addressed in any one lecture. These students would be able to break down this material and explain it to people with no prior knowledge of the subject. This presentation often takes a different form than the way it was presented to them in class; 8 Spring 2006 Syllabus B when students have a very good command of the main ideas of the subject matter. These students would be able to give out the course material in a manner similar to which it was given to them; C they are similar to a B student accept that command of the main ideas is rudimentary and fragmented; D when students have very little knowledge of the subject matter, but demonstrate at the very least that they recognize some of the material that has been presented to them; U when students have clearly made no effort to learn. Their performance is indicative of such and their work shows no interest in the subject matter and does not demonstrate that the material is even familiar to them. Please read pages 22 and 23 of the 2005 Student Handbook. These are the sections on Academic Honesty and Dishonesty. Course Topics We have 13+ weeks of class and only 39 class hours to work with. In order to keep the pace of the course flexible and the content adaptable, I will include an outline of the topics and text readings I’d like to cover, but the specific dates (as well as the topics) and relevant readings are subject to change. I will put the supplemental readings on the course readings section of the webpage. The mandatory text readings can be found in the list below. 1. The Economic Way of Thinking - What's Different About Economics? a. Mankiw - Chapter 2 b. Harford - Chapter 1 c. Mankiw - Chapter 1 d. Harford - Chapter 10 2. Economic Fundamentals - Scarcity, Choice, Trade, Systems a. Mankiw - Chapter 3 b. If you want to read ahead, you can also read Harford, Chapter 9, but we may cover it in section 5. 3. Understanding Demand and Supply a. Mankiw - Chapter 4 pp. 63-71; Chapter 5 pp. 89-100; Chapter 7 pp. 137-143 b. Mankiw - Chapter 4 pp. 71-75; Chapter 5 pp. 100-104; Chapter 7 pp. 143-147 c. Mankiw - Chapter 4 pp. 75-85; Chapter 5 pp. 104-109 4. Demand and Supply Applications and Government Policies a. Mankiw – Chapter 6 b. Harford – Chapter 3 5. Evaluation of the Market Mechanism and More Applications a. Mankiw – Chapter 7 pp. 147-154 b. Harford – Chapter 8 c. Mankiw – Chapter 8 d. Mankiw – Chapter 9 e. Harford – Chapter 9 9 Spring 2006 Syllabus 6. Special Section: Risks and Uncertainty a. See website for suggested readings. 7. Entrepreneurs, Profits and Losses a. Harford – Chapter 6 b. Mankiw – Chapter 12 pp. 243-247 8. Business Costs – How to Produce in the Short and the Long Run; Firm Behavior in Markets Absent Market Power a. Mankiw – Chapter 12 pp. 247-260 b. Harford - Chapter 2 c. Mankiw – Chapter 13 9. Special Section: The Economics of Health Care a. Harford – Chapter 5 b. See website for additional recommended readings. 10. When the “Invisible Hand” Develops Extra Thumbs: Price Searching and Market Power a. Mankiw – Chapter 14 11. When the “Invisible Hand” Develops Extra Thumbs: Externalities a. Mankiw – Chapter 10 b. Harford – Chapter 4 pp. 79-102 c. Mankiw – Chapter 11 d. Harford – Chapter 4 pp. 102-108 12. The “Distribution” of Income a. Mankiw Lecture Notes – see course readings for pdf b. See website for additional recommended readings. 13. Macroeconomics: Measuring Output a. Mankiw - Chapter 15 14. Macroeconomics: Measuring Prices a. Mankiw - Chapter 16 15. Macroeconomics: The Monetary System, Money Growth, Inflation and the Gold Standard a. Mankiw - Chapter 21 b. Mankiw – Chapter 22 16. Macroeconomics (unlikely, but time permitting): Ch17 to Ch 20; Production & Growth, the Financial System, Financial Tools, Unemployment and the Natural Rate 10