Titanic background and evaluation

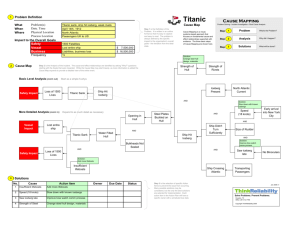

advertisement

Titanic Background Information The disaster of the Titanic was one of the biggest events that ever happened in the 20th century. The fact that so many people from all over the world, of all different classes, were victims of the disaster, affected people who were not even involved. The Titanic disaster was the combination of different avoidable events, with each part leading to devastating consequences. However, by all accounts, Titanic did almost everything that it was required to do. Ship building and navigation procedures on her maiden voyage were according to regulations. It was a series of unfortunate events that led to the tragedy and subsequent changes to maritime rules and regulations. The addition of 4 collapsible boats to the 16 regulation lifeboats meant that the ship actually exceeded the number of Board of Trade required lifeboats. The Titanic’s lifeboats were thought to be sort of a “PR addition” to the ship, with the mindset that the public would feel more safe seeing them; however, White Star Line felt that they would never need to use them except to perhaps shuttle people back and forth or to use them to help rescue other passengers on other distressed ships. Passengers weren’t the only ones awed by the ship’s dimensions. Many of the crew, hired at the last moment, were unprepared to handle the vast ship. Most of the crew didn’t know each other and weren’t quite sure of their duties and responsibilities. Even the ship’s highly experienced senior officers were overwhelmed. Passengers came from all walks of life. First class boasted some of the wealthiest and most socially elite. Hundreds of hopeful immigrants, looking for a better start in the United States, made up the 771 third class, or steerage class, passenger list. Many of the third class passengers were going to America to start a new life and many had sold everything they had owned, with the exception of a few possessions. Much of the first class mentality was that the third class passengers were inferior or beneath them. To some first class passengers, third class filled up extra space that could have been used for better things. On April 10, 1912, Titanic began her maiden voyage. She left Southampton at noon and was expected to reach New York in just 7 days. She travelled with 2,228 people onboard. On April 11, Titanic made her last stop in Queenstown, Ireland. She then set sail for open waters, carrying only enough lifeboats for about half of the people on board. The winter of 1912 had been unusually warm and a large number of icebergs had broken off from the Greenland coast and were drifting south with the Labrador Current and towards the North Atlantic shipping lanes. Starting on Friday, April 12th and continuing until throughout the day on Sunday, April 14th, the Titanic received at least 15 messages warning her of hazardous ice fields ahead. Inundated with hundreds of personal messages sent to and from the ship’s wealthy passengers, radio officers only periodically relayed these warnings to the bridge. It was the duty of the wireless officers to relay these passenger messages if they wanted to get paid, and that took precedence over everything else. A ship sending a message that they had passed an iceberg or had some weather condition would be delivered to the bridge at their convenience. When put together, the most recent warnings indicated a giant ice field of nearly 80 miles, directly in the ship’s path. But no one thought to put the messages together and most the warnings that had been taken to the bridge went largely unnoticed. The bridge officers were convinced that if they did see an iceberg ahead, they would see it in plenty of time to take evasive action. Another concern was the misplacement of the ship’s binoculars used by the lookout in the crow’s nest to spot obstacle in the ship’s path. Because of the shuffling around of officers shortly before the voyage, no one could locate where the ship’s binoculars had been stored, so the officers in the crow’s nest were making due without them. At 11:40pm, one of the officers spotted a shape looming off in the distance growing larger by the second. Ringing the bell, he telephones the bridge with the message that an iceberg is directly in front of them. Unbeknownst to the lookout crew, because the water was so flat, they couldn’t see the iceberg until it was too late. Waves are needed to break around the base of an iceberg to show it at a distance and the night of April 14th was absolutely moonless and as dark as could be, and there was no disturbance in the water. The iceberg was a rare iceberg by most accounts and it was a “blackberg” or a “blueberg”. This is an iceberg where the center of gravity, because of melting, shifted and slowly turned the iceberg upside down in the water and you now have clear ice above the water, not quite the snowy berg that one would imagine and it was virtually invisible that night. The subsequent decisions in the next seconds sealed Titanic’s fate. The decisions to reverse the engines and slow down the ship reduced the effectiveness of the ship’s rudder and these massive ships like the Titanic were already difficult to turn in a hurry anyway. It is speculated that if the first officer had just commanded full steam ahead and order the wheel to turn hard over, they probably would have missed the iceberg. At the last moment, the ship seemed to be clearing the iceberg, but the ship struck the ice lying below the surface, popping rivets, buckling plates and creating a gash below the waterline of nearly a third of the ship’s length. An initial assessment revealed that the Titanic was taking on water in at least 6 of Titanic’s watertight compartments. Even though the compartments had horizontal watertight bulkheads, they were not capped off with watertight tops, meaning that the water would fill up and flow ever into the next compartment. The ship’s builder, Thomas Andrews knew that if more than four of the ship’s compartments flooded, it would inevitably sink. He relayed this information to Captain Smith, stating that it was a “mathematical certainty”, and adding that in his opinion, the vessel had only about an hour before it completely sank. He also informed Smith of the severe shortage of lifeboats on the ship, only enough to save half of those onboard. There was a lot of confusion and rumors as to why the ship’s engines had suddenly stopped, and no one really seemed to know what was happening. One passenger reported that she was told to wait by a lifeboat because they were going to launch it, however the steward told her not to worry because they would be back onboard by breakfast time because it was just a precaution. At 12:10am, Captain Smith appeared in the radio room and told the wireless operators to send out calls for assistance. However, the urgency still hadn’t sunk in for the young wireless officers, with the surviving wireless officer stating that they “were making light of the situation” while sending out the distress calls. There is a question about how many people knew that it was a life threatening disaster. Very clearly Bruce Ismay, Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews knew the exact fate of the ship, but there is a lot of evidence that not many of the senior officers knew until very late how serious the problem was. This communication failure raised problems when trying to get people into the lifeboats. Not taking the problem seriously, many passengers were reluctant to go wait outside in the cold. It was very difficult for the first 45 minutes to get people into the first few lifeboats and indeed some of these first boats left with very few people on board. Some of them were only a third or a half full, fearing that they would sink with the weight, not realizing that these lifeboats had been tested in Belfast with 68 fully grown men in them. If it had not been for the ignorance of the officers in charge of the lifeboats and the reluctance of the passengers to go into those boats, they could have loaded the lifeboats with more people and saved more lives. One officer noted lights off the portside bow in the distance, which he took to be a steamer. Failing to contact the ship with the Morse lamp, at 12:45, officers began firing distress rockets. Although they failed to attract the ship’s attention, they brought a shock of reality to Titanic’s passengers. As water began to rose and the lifeboats fewer, panic began to ensue. Firearms were distributed to various officers manning the lifeboats to keep people from rushing the lifeboats. Third class was chaotic as people scrambled to find a way up to the upper decks. The way the ship was laid out proved to be very difficult for many third class passengers to get up on deck. Many spoke different languages, and with White Star line having so few interpreters, it wasn’t clear what they were to do. There was no organization for them, and in many respects, third class was simply neglected to death. There were reports of ship crew trying to keep third class people from getting to the upper decks, by blocking passages and closing gates. The wireless officers continued sending out SOS signals until the water reached the upper decks. Eventually contact was made with the Carpathian, the nearest ship. The captain made orders to make way to the Titanic at once, but they wouldn’t reach the ship in time. The Titanic sank at 2:20am, taking over 1,500 passengers and crew with her. Her surviving 710 passengers waited until almost dawn when they were rescued by the Carpathian. Immediately following the disaster, other ship lines began to take safety precautions, including taking a more southerly course and providing enough lifeboats and lifejackets for all passengers on vessels. A week had barely passed but Titanic had already changed forever the complacent era that built her. In the United States, Senator William Alden Smith demanded an immediate inquiry. He had a resolution passed in the Senate stating that anybody who used American ports were responsible for answers to questions when Americans were lost. He resolved to subpoena the crewman and any passengers that he needed to get the full story of the Titanic to be able to change legislation in the United States. Findings yielded that what had seemed negligent to Smith and the American people, wasn’t strictly a violation of written law. In May, the American inquiries were over and the surviving crew made their way to Plymouth, England, where they were summoned to appear before British inquiries. Neither of the inquiries fixed blame on the White Star line or its employees. But together, both hearings made possible far reaching regulatory changes that still protect seafarers today. They agreed that the number of lifeboats should be such that they can accommodate everyone on board, and they also agreed to create a service, which the United States took responsibility for, called the International Ice Patrol, that goes through the North Atlantic lanes and blows up icebergs before they become a hazard to navigation. In addition, wireless would need to be carried on any ship carrying a certain amount of passengers, and that there would have to be a 24 hour service on the wireless. Evaluation An evaluation of this case reveals that there were several concerns that could have addressed that would have saved more lives. In his original design, Alexander Carlisle, Harland and Wolfe managing director, believed that more lifeboats might be needed. He called for 48 lifeboats. But when Owner Bruce Ismay opted for 16, Carlisle did not press the point. Ismay felt that these extra lifeboats would take away space from the decks that could be used for leisure activities and the cramped deck space would increase the discomfort of the passengers. Due to lack of communication, there was no real sense of urgency on board with passengers in the second and first classes. Many joked and played around with the ice that had fallen on deck after the impact, thinking the ship to be unsinkable. However, many third class passengers, especially those in the forward part of the ship, had awoken to find water slowly entering their staterooms and realized the extent of the danger. A lot of modern conveniences of this time did not include a general alarm system or PA system to communicate with passengers. The way to inform people was haphazard. In first class, the stewards would knock on doors and inform passengers to put on their lifejackets and go up on deck and try to convince them that there was a problem. In second class, they would pound on doors, and in third class, they threw doors open and screamed at people, many of whom knew little or no English. Why was there not enough urgency instilled in these passengers? Why was there not enough urgency in the officers and the crew to make sure that these boats were filled so that none of them would go away less than full? One has to remember the fine line between urgency and creating panic and that may have been what was going through Captain Smith’s mind. Men of his stature were expected to behave in a certain way at that time. On the portside, Captain Smith’s orders of “women and children only” was taken as gospel. The only men allowed on these lifeboats were the crewmen needed to man them. Today we look back on the navigation techniques that the crewmen of the Titanic were used to and consider it negligent in hindsight; but at the time, they were doing everything they were supposed to: they had the lookouts posted, they had warned the lookouts about possible ice, they had ice warnings received that a few years ago wouldn’t have even been possible because of lack of the wireless, and yet ships weren’t hitting icebergs left and right, so they officers felt that they could successfully navigate around the ice without incident. Following the Titanic disaster, the confident era that had built her was changing forever. By 1913, the lavish lifestyles of the Edwardian rich would be dealt a further blow by the introduction of the Income tax. And no longer was it considered acceptable to sacrifice the lives of the less fortunate to save those of the wealthy. A disproportionate number of men died due to the women and children first protocol that was followed. As a consequence of this practice, 74% of the women on board were saved and 52% of the children, but only 20% of the men. Men and members of the 2nd and 3rd class were less likely to survive. Of the male passengers in second class, 92 percent perished. Less than a quarter of third-class passengers survived. Six of the seven children in first class survived, all of the children in second class survived, whereas less than half were saved in third class. 96 percent of the women in first class survived, 86 percent of the women survived in second class and less than half survived in third class. Overall, only 20 percent of the men survived, compared to nearly 75 percent of the women. Men in first class were four times as likely to survive as men in second class, and twice as likely to survive as those in third. After the Titanic disaster, recommendations were made by both the British and American Boards of Inquiry stating that ships would carry enough lifeboats for those aboard, mandated lifeboat drills would be implemented, and lifeboat inspections would be conducted, among other safety measures. Many of these recommendations were incorporated into the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea passed in 1914. In addition, the United States government passed the Radio Act of 1912. This act, along with the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, stated that radio communications on passenger ships would be operated 24 hours along with a secondary power supply, so as not to miss distress calls. Also, the Radio Act of 1912 required ships to maintain contact with vessels in their vicinity as well as coastal onshore radio stations. It was also agreed that the firing of red rockets from a ship must be interpreted as a distress signal. This decision was based on the fact that the rockets launched from the Titanic prior to sinking were interpreted with a bit of ambiguity by the freighter S.S. Californian. Officers on the Californian had seen rockets fired from an unknown liner from their decks, yet surmised that they could possibly be "company" or identification signals, used to signal to other ships. At the time of the sinking, aside from distress situations, it was commonplace for ships without wireless radio to use rockets to identify themselves to other liners. Once the Radio Act of 1912 was passed it was agreed that rockets at sea would be interpreted as distress signals only, thus removing any possible misinterpretation from other ships. Following the Titanic disaster, ships were refitted for increased safety. One measure taken into effect was that the double bottoms of many existing ships, were extended up the sides of their hulls, above their waterlines, to give them double hulls. Another refit that many ships underwent were changes to the height of the bulkheads. The bulkheads on Titanic extended 10 feet (3 m) above the waterline. After the Titanic sank, the bulkheads on other ships were extended higher to make the compartments fully watertight.