Sample Timeline for Developing a Career Plan

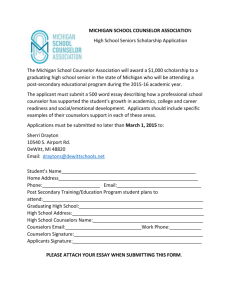

advertisement