The Insanity Defense

How can a person who admits committing a crime be found "not guilty by reason of insanity?"

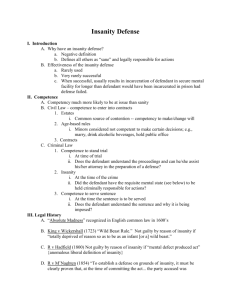

In this context, "not guilty" does not mean the person did not commit the criminal act for which he or she is charged. It means that when

the person committed the crime, he or she could not tell right from wrong or could not control his or her behavior because of severe

mental defect or illness. Such a person, the law holds, should not be held criminally responsible for his or her behavior. The legal test

for insanity varies from state to state.

Are "sane" and "insane" medical terms?

No. The word "insane" is a legal term. Because research has identified many different mental illnesses of varying severities, it is now

too simplistic to describe a severely mentally ill person merely as "insane." Although most people with mental illness do not commit

crimes, of those who do, the vast majority would be judged "sane" if current legal tests for insanity were applied to their criminal

behaviors.

Don't many criminals try to use the insanity defense to escape severe punishment?

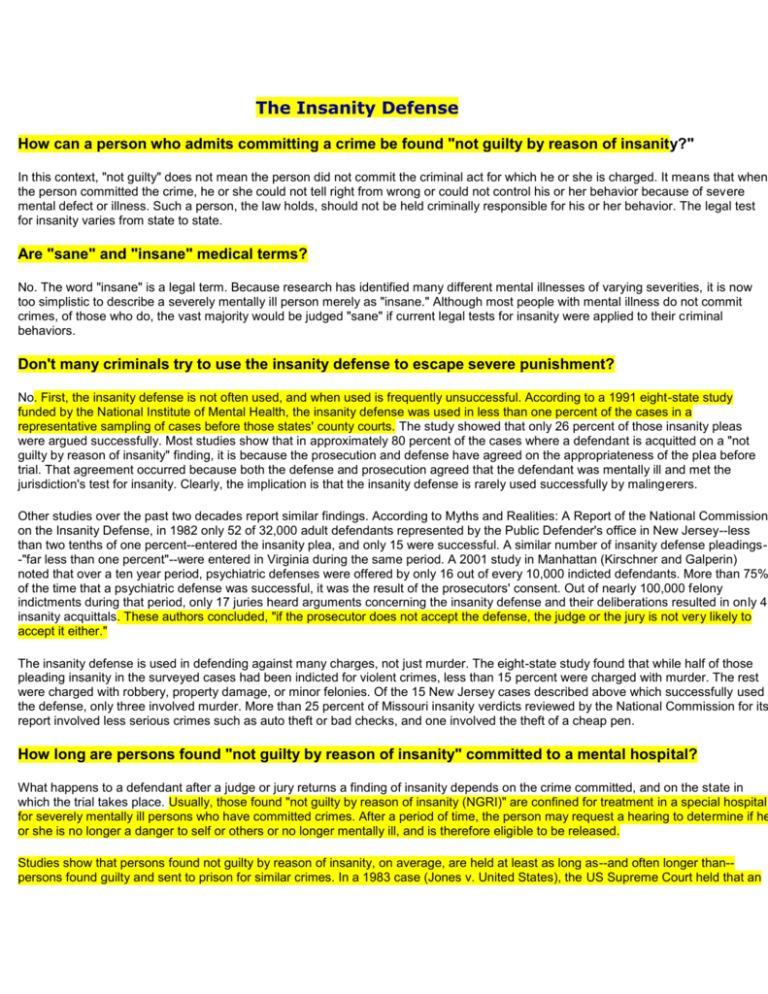

No. First, the insanity defense is not often used, and when used is frequently unsuccessful. According to a 1991 eight-state study

funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, the insanity defense was used in less than one percent of the cases in a

representative sampling of cases before those states' county courts. The study showed that only 26 percent of those insanity pleas

were argued successfully. Most studies show that in approximately 80 percent of the cases where a defendant is acquitted on a "not

guilty by reason of insanity" finding, it is because the prosecution and defense have agreed on the appropriateness of the plea before

trial. That agreement occurred because both the defense and prosecution agreed that the defendant was mentally ill and met the

jurisdiction's test for insanity. Clearly, the implication is that the insanity defense is rarely used successfully by malingerers.

Other studies over the past two decades report similar findings. According to Myths and Realities: A Report of the National Commission

on the Insanity Defense, in 1982 only 52 of 32,000 adult defendants represented by the Public Defender's office in New Jersey--less

than two tenths of one percent--entered the insanity plea, and only 15 were successful. A similar number of insanity defense pleadings-"far less than one percent"--were entered in Virginia during the same period. A 2001 study in Manhattan (Kirschner and Galperin)

noted that over a ten year period, psychiatric defenses were offered by only 16 out of every 10,000 indicted defendants. More than 75%

of the time that a psychiatric defense was successful, it was the result of the prosecutors' consent. Out of nearly 100,000 felony

indictments during that period, only 17 juries heard arguments concerning the insanity defense and their deliberations resulted in only 4

insanity acquittals. These authors concluded, "if the prosecutor does not accept the defense, the judge or the jury is not very likely to

accept it either."

The insanity defense is used in defending against many charges, not just murder. The eight-state study found that while half of those

pleading insanity in the surveyed cases had been indicted for violent crimes, less than 15 percent were charged with murder. The rest

were charged with robbery, property damage, or minor felonies. Of the 15 New Jersey cases described above which successfully used

the defense, only three involved murder. More than 25 percent of Missouri insanity verdicts reviewed by the National Commission for its

report involved less serious crimes such as auto theft or bad checks, and one involved the theft of a cheap pen.

How long are persons found "not guilty by reason of insanity" committed to a mental hospital?

What happens to a defendant after a judge or jury returns a finding of insanity depends on the crime committed, and on the state in

which the trial takes place. Usually, those found "not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI)" are confined for treatment in a special hospital

for severely mentally ill persons who have committed crimes. After a period of time, the person may request a hearing to determine if he

or she is no longer a danger to self or others or no longer mentally ill, and is therefore eligible to be released.

Studies show that persons found not guilty by reason of insanity, on average, are held at least as long as--and often longer than-persons found guilty and sent to prison for similar crimes. In a 1983 case (Jones v. United States), the US Supreme Court held that an

NGRI acquittee "could be confined to a mental hospital for a period longer than he could have been incarcerated had he been

convicted."

The insanity defense got a lot of attention when John Hinckley--the man who shot President Reagan to

impress the actress Jody Foster--used it in his trial. Has that had any impact on the way the states look

at it?

Yes. In the wake of the attention John Hinckley's trial received, many states and the Congress sought ways to restrict use of the

defense. Many people worried that those found not guilty by reason of insanity might be released too easily from secure hospitals and

would cause harm again. To answer this concern, some states have created review boards--much like parole boards--that take

administrative responsibility for those who have come to institutions after a successful insanity plea. The boards oversee the treatment

provided and can set conditions that must be met if a person is to be released or is to remain in the hospital.

In Connecticut, for instance, in cases where the insanity defense is successfully argued, the presiding judge determines the amount of

time the person would have been incarcerated had they been found sane and convicted for the crime they committed. The judge then

specifies that the state's review board has control of the convicted person until this period lapses. Other states apply a rule that these

people must be held until an evaluation finds them no longer dangerous or mentally ill.

So different states look at the insanity defense differently?

Yes. Each of the fifty states and the District of Columbia has its own statute. Each jurisdiction applies similar principles, but the

procedures and criteria used for a finding of insanity vary.

The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law has developed a practice guideline for insanity defense evaluations that offers a

useful review of historical and current practices [Journal Am Acad Psychiatry Law 30 (Supp 2), 2002]. According to that review, about

one third of the states have adopted a test for the insanity defense modeled on a standard written during the 1950's by the American

Law Institute (ALI).That test holds that a person would "not [be] responsible for criminal conduct if at the time of such conduct as a

result of mental disease or defect he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality (wrongfulness) of his conduct or to

conform his conduct to the requirements of law." About half the states currently use some variation of` the narrower M'Naghten Rule, an

insanity definition derived from English case law, which holds that a person is "innocent by reason of insanity [if] at the time of

committing the act, he was laboring under such a defect of reason from disease of the mind as not to know the nature and quality of the

act he was doing, or if he did know it, that he did not know what he was doing what was wrong." Three states have added a reference

to "irresistible impulse," and four states (Montana, Idaho, Utah, and Kansas) have legislatively abolished the insanity defense. New

Hampshire's standard is the now rare "product of mental illness test," i.e., defendants can be found NGRI if their criminal behavior is

determined to have resulted from their disorder.

Following the Hinckley case, Congress altered the U.S. Federal and military standards for the insanity defense, limiting it to the socalled "cognitive prong" of the ALI test--- that a defendant would not be responsible if "as a result of severe mental disease or defect,

[he] was unable to appreciate the nature and quality or the wrongfulness of his acts." Altogether, ¾ of the states and the Federal

government have imposed some form of insanity defense reform since Hinckley's 1982 acquittal.

In 1982, the American Psychiatric Association endorsed another standard, written by Richard Bonnie, a legal expert at the University of

Virginia, which states:

A person charged with a criminal offense should be found not guilty by reason of insanity if it is shown that as a result of mental disease

or mental retardation he was unable to appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct at the time of the offense. As used in this standard,

the terms "mental disease" or "mental retardation" include only those severely abnormal mental conditions that grossly and

demonstrably impair a person's perception or understanding of reality and that are not attributable primarily to the voluntary ingestion of

alcohol or other psychoactive substances.

The APA does not endorse the "irresistible impulse" test for insanity.

In recent years, some states have replaced the "not guilty by reason of insanity" plea with a "guilty but

mentally ill" plea, or added a finding of " guilty but mentally ill" as an additional option. Why?

This plea has arisen out of the perception that juries have had difficulty grappling with the issues of factual guilt and defendants' ability

to judge the morality of their actions. The "guilty but mentally ill" verdict is seen by some as one way the jury may sidestep these

questions, shuttling those who might otherwise "escape" into an insanity plea into a new category where they can be judged "guilty." It

is the APA's position that, while the "guilty but mentally ill" category may seem to make the jury's job easier, it avoids one of our criminal

justice system's most important functions--deciding, through its deliberations, how society defines responsibility. Moreover, since

persons found guilty but mentally ill (GBMI) are punished in the same way as those found guilty, use of this verdict may mislead jurors

about the consequences of their decisions. Persons found GBMI typically do not receive specialized mental health services beyond

what is normally available in a prison setting. The APA does not support the "guilty but mentally ill" plea as a substitute for, or

supplement to, the insanity defense.

Shouldn't psychiatrists be the ones to determine whether someone with a mental illness is really

responsible for his or her actions? After all, they're the experts.

No. Psychiatrists' years of training and experience make them experts at diagnosing and treating mental illnesses. They can offer

testimony on the probable nature and severity of the defendant's illness at the time of the crime, and offer other medical and

psychological explanations for behavior. But that is the extent of their expertise: they are trained in medicine, not the law. It is the job of

the judge or jury, as society's representative, to determine criminal responsibility.

If psychiatrists who testify for the prosecution and the defense give different opinions during a trial,

doesn't that imply there's a lot of guesswork in psychiatric diagnoses?

The use of experts is part of our adversarial court system--lawyers for the prosecution and the defense often employ experts, such as

heart surgeons, radiologists or engineers, who will give differing testimony during a trial. A difference of opinion among testifying

psychiatrists doesn't imply that the doctors have a murky understanding of mental illnesses. Studies show that psychiatric diagnoses,

especially of severe illnesses, are about 80 percent reliable--on a par with diagnoses of other medical illnesses. As with other medical

problems--such as cancer or a back injury--a mental illness can have different effects on different people. Even two psychiatrists who

disagree on the fine points of a defendant's illness might be in complete agreement on its basis and effect.

For further detail, see: APA "Statement on the Insanity Defense" December 1982

For further information, contact:

American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law

P.O. Box 30

One Regency Dr.

Bloomfield, CT 06002

(860) 242-5450

www.aapl.org

American Bar Association

750 North Lake Shore Drive

Chicago, IL 60611

(312) 988-5000

www. Abanet.org

How to Order "Let's Talk Facts About ..." Pamphlets

APA Consumer Resources List

First posted: 1/9/96; revised 9/03

Email comments or questions

1000 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1825, Arlington, Va. 22209-3901

phone: 703-907-7300 email: apa@psych.org © Copyright 2004 All Rights Reserved