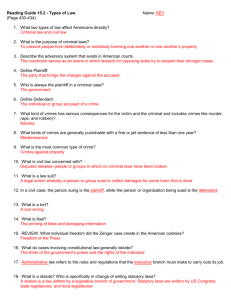

NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW

advertisement

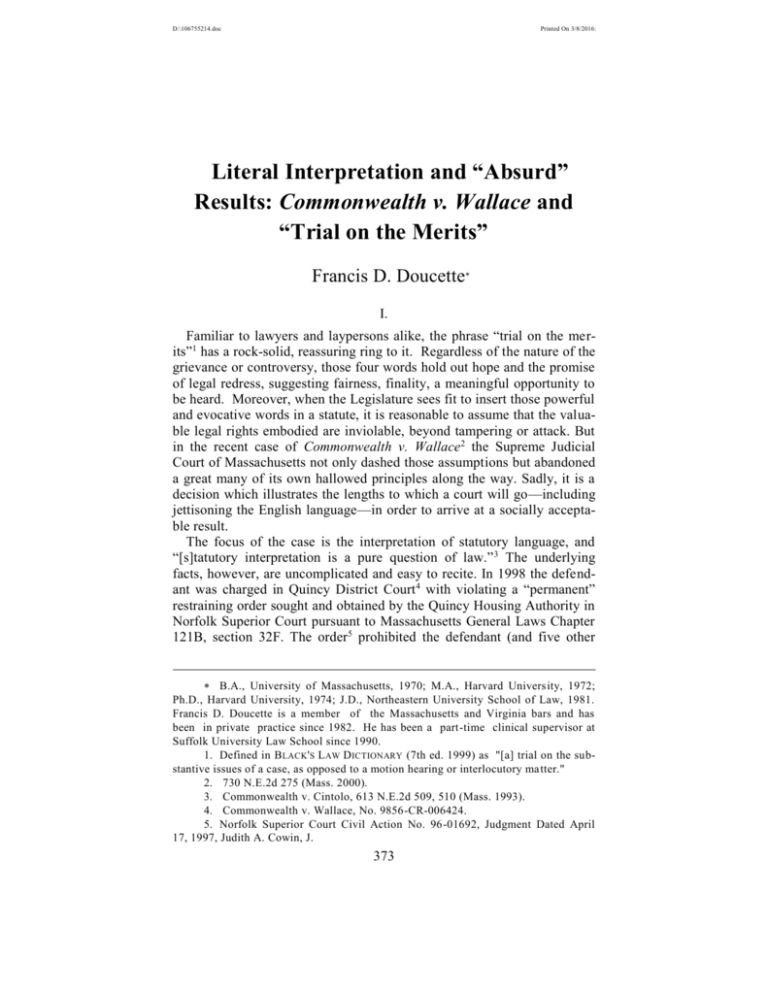

D:\106755214.doc Printed On 3/8/2016: Literal Interpretation and “Absurd” Results: Commonwealth v. Wallace and “Trial on the Merits” Francis D. Doucette I. Familiar to lawyers and laypersons alike, the phrase “trial on the merits”1 has a rock-solid, reassuring ring to it. Regardless of the nature of the grievance or controversy, those four words hold out hope and the promise of legal redress, suggesting fairness, finality, a meaningful opportunity to be heard. Moreover, when the Legislature sees fit to insert those powerful and evocative words in a statute, it is reasonable to assume that the valuable legal rights embodied are inviolable, beyond tampering or attack. But in the recent case of Commonwealth v. Wallace2 the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts not only dashed those assumptions but abandoned a great many of its own hallowed principles along the way. Sadly, it is a decision which illustrates the lengths to which a court will go—including jettisoning the English language—in order to arrive at a socially acceptable result. The focus of the case is the interpretation of statutory language, and “[s]tatutory interpretation is a pure question of law.” 3 The underlying facts, however, are uncomplicated and easy to recite. In 1998 the defendant was charged in Quincy District Court 4 with violating a “permanent” restraining order sought and obtained by the Quincy Housing Authority in Norfolk Superior Court pursuant to Massachusetts General Laws Chapter 121B, section 32F. The order5 prohibited the defendant (and five other B.A., University of Massachusetts, 1970; M.A., Harvard University, 1972; Ph.D., Harvard University, 1974; J.D., Northeastern University School of Law, 1981. Francis D. Doucette is a member of the Massachusetts and Virginia bars and has been in private practice since 1982. He has been a part-time clinical supervisor at Suffolk University Law School since 1990. 1. Defined in B LACK 'S LAW D ICTIONARY (7th ed. 1999) as "[a] trial on the substantive issues of a case, as opposed to a motion hearing or interlocutory ma tter." 2. 730 N.E.2d 275 (Mass. 2000). 3. Commonwealth v. Cintolo, 613 N.E.2d 509, 510 (Mass. 1993). 4. Commonwealth v. Wallace, No. 9856-CR-006424. 5. Norfolk Superior Court Civil Action No. 96-01692, Judgment Dated April 17, 1997, Judith A. Cowin, J. 373 D:\106755214.doc 374 Printed On 3/8/2016: NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 36:2 named individuals) “from entering or remaining within one thousand (1000) feet”6 of specified property of the Quincy Housing Authority. The last sentence of the second paragraph of Chapter 121B, section 32F, states in forceful, seemingly unambiguous terms that “[n]o permanent [restraining] order shall be granted except as a final judgment after a trial on the merits.”7 And any order so issued, whether temporary or permanent, is required by the first paragraph of the same statute to “contain the following statement: VIOLATION OF THIS ORDER IS A CRIMINAL OFFENSE” (capitals in original). 8 Thus there is no question that Chapter 121B, section 32F, is a penal statute; the maximum penalties are a fine of up to $3,500 and imprisonment for up to two years in the house of correction, or both. It was uncontroverted that the defendant never had a trial on the merits because he defaulted in Superior Court; even the final judgment prominently9 acknowledged that fact. Indeed, at the time of the civil trial the defendant was incarcerated. Relying on this background and the plain wording of the statute, the defendant's attorney filed a motion and a memorandum10 seeking dismissal of the complaint. The primary contention was that the “permanent” restraining order issued was a legal nullity since no trial on the merits had ever taken place, in contradiction of the statutory mandate. Accordingly, the Commonwealth could not prevail in a criminal trial because it could not establish a knowing 11 violation of a valid order. Secondarily, the defendant exhorted the court to respect the legislative intent in insisting on a trial on the merits and to abide by the maxim that criminal statutes must be strictly construed. On these (or some other) grounds the district court judge, of course, could have dismissed the complaint sua sponte. 12 But the Commonwealth, assisted by counsel for the Quincy Housing Authority, opposed the motion to dismiss, and, after a hearing, the judge denied it. Conceding, however, that “these are questions of law which are important and where the law is in doubt,”13 the judge, pursuant to Rule 34, reported two questions of law 14 6. Id. 7. M ASS. GEN. LAWS ch. 121B § 32F (2001). 8. Id. 9. See Norfolk Superior Court Civil Action No. 96-01692, Judgment Dated April 17, 1997, Judith A. Cowin, J. 10. See Commonwealth v. Wallace, No. 9856-CR-006424. 11. The defendant, however, was served in hand with a copy of the restraining order. See Commonwealth v. Wallace, 730 N.E.2d 275, 277 (Mass. 2000). 12. “We take this occasion to note that a judge has inherent authority to dismiss an indictment sua sponte. This is a necessary corollary of the judge's authority to process criminal cases.” Commonwealth v. Jenkins, 727 N.E.2d 1172, 1174 -75 (Mass. 2000). 13. Report pursuant to M.R.C.P. 34 of Mark S. Coven, J., Docket No. 9856 -CR- D:\106755214.doc 2002] “TRIAL ON THE MERITS” Printed On: 3/8/2016 375 to the appeals court. The Supreme Judicial Court then transferred the case on its own initiative, albeit skewering the action as procedurally defective on several fronts. The defendant, the court first maintained, should not be allowed to challenge the validity of the permanent restraining order in the motion to dismiss the criminal case. Such a challenge, in the court's view, amounted to an impermissible “collateral attack,”15 an approach disfavored and rejected by the court in an appeal of a criminal contempt case just the year before.16 The court went on to explain that other options and remedies 17 were available to the defendant, had he wished to contest the issuance of the restraining order; none of which the defendant pursued. Additionally, the court even questioned the propriety 18 of the district court judge reporting the questions of law to the appeals court, intimating that the matter was not appropriate for interlocutory appeal. Indeed, ultimately the court ruled that “[t]he report is discharged as not being properly before us.”19 All of this caviling fairly begs the question why the court ever bothered to accept such a supposedly error-riddled case for review in the first place. Nonetheless, once having disinfected the air of these procedural irregularities, the court proceeded swiftly to an analysis of the defendant's main contention, agreeing with the district court judge that “the issues raised by the reported questions are important.”20 II. The analysis is abbreviated, occupying barely more than a page, and is more remarkable for what it leaves out than for what it includes. Throughout, the court seems uneasy or reluctant even to acknowledge that it is dealing with a criminal case. For example, the concept of liberty and the potential loss of that liberty never figure in the discussion. The court quotes or cites a total of six cases in the analysis, five of which are civil and all from Massachusetts, and never hints that special concerns are sup- 006424. 14. The two questions were: "(1) Can the Superior Court, pursuant to M.G.L.c.121B, sec.32A et seq., grant a permanent injuction on behalf of a public hou sing authority only after a trial on the merits? (2) Must the District Court dismiss a criminal complaint for a violation of a permanent injunction entered pursuant to M.G.L.c.121B, sec.32F where that injunction entered after the default of the defendant and not after a trial on the merits?" Wallace, 730 N.E.2d at 276-77. 15. Id. at 277. 16. See Commonwealth v. Dodge, 705 N.E.2d 612 (Mass. 1999). 17. See Wallace, 705 N.E.2d at 277. 18. See id. at 276 n.1. 19. Id. at 278. 20. Id. at 276-77. D:\106755214.doc 376 Printed On 3/8/2016: NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 36:2 posed to apply in the interpretation of a criminal statute. Obviously, the court knows better, as it has admitted elsewhere in analogous circumstances: “[t]he considerations underlying the proper application of a criminal statute are different.”21 There is no mention in the analysis whatever of the celebrated rule that “[c]riminal statutes are to be construed strictly against the Commonwealth and in favor of the defendant, under the premise that '[n]o one may be required at peril of life, liberty or property to speculate as to the meaning of penal statutes.”22 No idle academic exercise, this rule—sometimes referred to as the rule of lenity—has its origins in the common law23 and can be traced to the beginnings of the Republic.24 The historical basis of the rule is generally assumed to be the cruel and barbarous punishments of earlier ages, which enlightened judges and courts sought to circumvent by fashioning and applying the practice of strict construction. 25 To be sure, there is authority to the effect that the rule of strict construction, as an aid in interpretation, is limited to statutory language which admits of ambiguity. “There is no need of construction to ascertain the meaning of a statute where the language is clear and unambiguous and the intention of the law-making power is manifestly apparent therefrom.” 26 A 1984 decision27 of the United States Supreme Court reflects this sentiment: “The rule of lenity is of course a well-recognized principle of statutory construction . . . but the critical language of [18 U.S.C.S. § 1001] is not sufficiently ambiguous, in our view, to permit the rule to be controlling here.”28 But that narrow position, limiting the rule of strict construction to cases clouded by ambiguous statutory language, is far from universally held. Almost two centuries ago, Chief Justice John Marshall observed that “[t]he rule that penal laws are to be construed strictly, is perhaps not much 21. Commonwealth v. Chapman, 744 N.E.2d 14, 17 (Mass. 2001). 22. Commonwealth v. McLaughlin, 726 N.E.2d 959, 966 (Mass. 2000) (cit ations omitted). 23. "It is required at common law that a criminal statute be strictly construed, and that any doubt be resolved in favor of the defendant." WHARTON 'S CRIMINAL LAW (15th ed. 1993), § 12 and cases cited. See also P AUL H. R OBINSON , CRIMINAL LAW DEFENSES (1984), § 35(a)(2) n.6 (citing Livingston Hall, Strict or Liberal Construction of Penal Statutes, 48 HARV . L. REV. 748, 750-51 (1935): "The rule of strict construction was developed in England before the 19th Century, when courts sought to ameliorate the harsh penalties imposed for many offenses by narrowing the scope of a statute through strict construction."). 24. See United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U.S. 76 (1820). 25. See supra note 23 and accompanying text. 26. People v. Lund, 46 N.E.2d 929 (Ill. 1943). 27. See United States v. Rogers, 466 U.S. 475 (1984). 28. Id. at 484. D:\106755214.doc 2002] “TRIAL ON THE MERITS” Printed On: 3/8/2016 377 less old than construction itself.” 29 A leading authority on Massachusetts criminal law asserts succinctly and without qualification that “a criminal statute must be construed strictly. The court may not enlarge a criminal statute by implication.”30 To illustrate, relying on that general principle, and making no finding or argument regarding ambiguity, the court in Commonwealth v. Cintolo31 affirmed the allowance of a motion to dismiss by ruling, as a matter of law, that the defendant corporate president “was not the 'person having employees,' within the language of Massachusetts General Laws Chapter 149, section 150C.” 32 In Commonwealth v. Boone,33 which dealt with the definition of “escape” in Massachusetts General Laws Chapter 268, section 16, the court engaged in no discussion of ambiguity but firmly declined to enlarge upon the statute under review: “To create such a fiction on the language of s[ection] 16 alone runs contrary to the usual tenet of strict construction of a criminal statute.”34 Of course, regardless of whether ambiguity is a factor, there are limits to the rule of strict construction. For example, in Commonwealth v. Roucoulet,35 the defendant was arrested in a motor vehicle within 1000 feet of a school zone in possession of a “large quantity of cocaine, cutting agents,”36 baggies, and the like. He elected to plead guilty to the indictment which charged him with trafficking in cocaine, but disputed, both at a jury-waived trial and on appeal, the separate indictment which charged him with violation of the school zone statute. Proof was lacking, the defendant contended, that he had any intention to distribute these drugs inside the school zone; on the contrary, even the Commonwealth's evidence established convincingly that the drugs were destined to be delivered to an undercover police officer then waiting at a co-defendant's home outside the prohibited 1000 foot area. The court, however, refused to read into the statute any requirement that there must be proof of an intent to distribute within the school zone. “The maxim that criminal statutes are to be strictly construed,” Justice Greaney wrote, “does not mean that an available and sensible interpretation is to be rejected in favor of a fanciful or perverse one.”37 The more general rule, as stated in a United States Supreme Court decision38 from 1976, is that “[a] criminal statute . . . is to be strictly con- 29. Wiltberger, 18 U.S. at 95. 30. JOSEPH P. NOLAN & LAURIE J. S ARTORIO , 32 M ASSACHUSETTS P RACTICE § 8 (3d ed. 2001). 31. 613 N.E.2d 509 (Mass. 1993). 32. Id. at 359. 33. 477 N.E.2d 1026 (Mass. 1985). 34. Id. at 1029. 35. 601 N.E.2d 470 (Mass. 1992). 36. Id. at 471. 37. Id. at 473. 38. Barrett v. United States, 423 U.S. 212 (1976). D:\106755214.doc 378 Printed On 3/8/2016: NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 36:2 strued, but it is ‘not to be construed so strictly as to defeat the obvious intention of the legislature.’”39 III. In Wallace, however, the court refrains from ever declaring, at least explicitly, whether it finds ambiguous the phrase “trial on the merits” in Chapter 121B, section 32F. The accepted wisdom is that “[a] term is ambiguous only if it is susceptible of more than one meaning and reasonably intelligent persons would differ as to which meaning is the proper one.”40 Certainly, when inclined, the court knows how to say that some word or combination of words is “not ambiguous” 41 or that the words of a statute “are plain.”42 Whether this omission in Wallace is inadvertent or calculated, it obviously allows the court the luxury to bypass the rule of strict construction and deny the defendant the deferential treatment to which he would otherwise be entitled. “If the statutory language ‘can plausibly be found to be ambiguous,’ the rule of lenity requires the defendant to be given ‘the benefit of the ambiguity.’”43 Similarly, in the absence of an explicit finding of ambiguity, “there is no occasion to examine legislative history,” 44 and no justification to “look to extrinsic circumstances to determine the intent of the Legislature as to [the statute's] meaning.” 45 The polar opposite of ambiguous language is clear or plain language. “It is a well-established canon of construction that, where the statutory language is clear, the courts must impart to the language its plain and ordinary meaning.”46 As it should be, “the statutory language itself is the principal source of insight into the legislative purpose.” 47 It would be ludicrous and futile to suggest that the Legislature was not familiar with the 39. Id. at 218 (quoting American Fur Co. v. United States, 2 Pet. 358, 367, 7 L. Ed. 450 (1829) and citing Huddleston v. U.S., 415 U.S. 814, 831 (1974)). 40. County of Barnstable v. American Fin. Corp., 744 N.E.2d 1107, 1109 (Mass. App. Ct. 2001). 41. Roucoulet, 601 N.E.2d at 473. 42. Daluz v. Dept. of Corr., 746 N.E.2d 501, 508 (Mass. 2001) (stating "[t]he words of G. L. c.30, s.58, are plain."). 43. Commonwealth v. Carrion, 725 N.E.2d 196, 198 (Mass. 2000) (quoting Roucoulet, 601 N.E.2d at 473). 44. Roucoulet, 601 N.E.2d at 472 n.7. 45. EMC Corp. v. Comm’r of Revenue, 744 N.E.2d 55, 57 (Mass. 2001). 46. Commonwealth v. One 1987 Mercury Cougar Auto., 600 N.E.2d 571, 573 (Mass. 1992). See also Caminetti v. United States, 242 U.S. 470, 485 (1917) (stating "[w]here the language is plain and admits of no more than one meaning, the duty of interpretation does not arise, and the rules which are to aid doubtful meanings need no discussion."). 47. Hoffman v. Howmedica, Inc., 364 N.E.2d 1215, 1218 (Mass. 1977). D:\106755214.doc 2002] “TRIAL ON THE MERITS” Printed On: 3/8/2016 379 legal meaning and significance of “trial on the merits” when it drafted section 32F of Chapter 121B. “It is to be presumed . . . that the legislature is acquainted with the law, that it has knowledge of the state of the law on subjects on which it legislates . . . .”48 Beyond doubt, the phrase “trial on the merits” in section 32F of Chapter 121B is a laudable example of the deliberate use of clear, plain language. Only a sophist or contrarian would contend otherwise. But the court in Wallace declines to give those four words either praise or meaning. Instead, the court, in its abbreviated analysis, defeats the defendant's claim by selecting and championing one dubious, obscure canon of statutory construction, at the expense of all other canons. It borrows and quotes this canon from a 1979 civil case: 49 “[a] literal construction of statutory language will not be adopted when such a construction will lead to an absurd and unreasonable conclusion . . . .” 50 The subject matter of the 1979 civil case—a wrangling over the interpretation of the phrase “any town” in a dispute between two towns concerning the reimbursement of veterans' benefits—obviously has nothing to do with criminal jurisprudence and the potential loss of liberty at stake in the instant case. Nonetheless, with that doctrine as its sole guide, the court acknowledges but disagrees with the defendant's argument that the phrase “trial on the merits” in Massachusetts General Laws chapter 121B, section 32F, should be given a literal interpretation. “[S]uch an interpretation,” the court declares flatly, “would lead to an absurd result.” 51 What would that absurd result be? “It would mean,” the court endeavors to explain, “that no permanent injunction could ever issue against an individual who defaulted in a civil action where a restraining order was sought . . . .” 52 Even if that consequence is conceded, is that not a matter for the Legislature to address, by an appropriate amendment to Chapter 121B, section 32F? As the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court has stated in various forms when confronted with similar problems before, “[t]he solution to the dilemma . . . is in the hands of the Legislature.” 53 But ignoring for the moment the avenue of legislative correction of a possibly flawed statute, is the court being honest when it depicts the present state of affairs in Wal- 48. Commonwealth v. Boarman, 610 S.W.2d 922, 924 (Ky. App. 1981). See also Commonwealth v. Smith, 710 N.E.2d 1003, 1005 (Mass. App. Ct. 1999) aff’d, 728 N.E.2d 272 (Mass. 2000) (stating "[f]urther, '[t]he Legislature must be assumed to know the preexisting law and the decisions of [the Supreme Judicial C]ourt.'"). 49. See Town of Lexington v. Town of Bedford, 393 N.E.2d 321 (Mass. 1979). A more recent expression of this rule may be found in Johnson Lumber v. Woodscape Homes, Inc., 746 N.E.2d 533, 536 (Mass. App. Ct. 2001) (citing various authorities ). 50. Town of Lexington, 393 N.E.2d at 327. 51. Wallace, 730 N.E.2d at 278. 52. Id. 53. Dodge, 705 N.E.2d at 616. D:\106755214.doc 380 Printed On 3/8/2016: NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 36:2 lace as an absurd result? Or, rather, is it a result the court simply does not like and refuses to let stand? Is the decision based on accepted, wellsettled principles of constitutional criminal law? Or, rather, is it the product of political correctness and social engineering? No fewer than four public housing authorities filed amicus briefs in the case. 54 Of course, “[t]he longstanding rule is that an amicus curiae is not a party to the case . . . .”55 The court adopts an alarmist tone and hastens to point out that one of the principal purposes of the statute is “to allow a housing authority to create a safe public housing environment, by protecting tenants from the unlawful actions of nontenants.”56 Such a goal is clearly commendable, but has it been thwarted or made impossible by the statutory requirement of a trial on the merits prior to the issuance of a permanent restraining order? The court implies as much but provides no data whatsoever in support. Indeed, the opinion is utterly devoid of statistics, crime reports, or accounts of frustrated efforts by public housing authorities to obtain permanent restraining orders to curb incidents of violence or disorders. Rather, without any such data and without apology, the court elevates public policy concerns over the rights of the defendant, paying scant attention to any other concerns. In the process, the court in essence treats “trial on the merits” as surplusage and all but deletes the phrase from Chapter 121B, section 32F. Oddly, the court never defines the operative label “absurd,” apparently viewing the word as self-defining.57 Nor does the court ever define “trial on the merits” or discuss the legal history or etymology of the phrase. While “not dispositive,” “[d]ictionary definitions are helpful . . . in statutory interpretation cases.”58 Equally disturbing, the court fails to cite a single authority, from any jurisdiction, where this particular canon of statutory construction was resorted to, dispositively or otherwise, in a criminal case.59 There are, moreover, no treatises on statutory construction mentioned or cited in Wallace. The pre-eminent work on the subject informs us that 54. Wallace, 730 N.E.2d at 276 n.2. 55. In re Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Inc., 746 N.E.2d 513, 518 (Mass. 2001). 56. Wallace, 730 N.E.2d at 278. 57. “Absurd” is defined as "[o]ut of harmony with reason or propriety; inco ngruous, unreasonable, illogical." OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY 43 (2d 1989). 58. Commonwealth v. Smith, 710 N.E.2d 1003, 1005 n.4 (Mass. App. Ct. 1999), further appellate review granted, 714 N.E.2d 825 (Mass. 1999), aff’d 728 N.E.2d 272 (Mass. 2000). 59. The single criminal case cited in the analysis, Commonwealth v. Williams, 691 N.E.2d 553 (Mass. 1998), is inapposite, having nothing to do with claims of a bsurd results but dealing rather with the proper interpretation of the juvenile transfer statute, the former Massachusetts General Laws Chapter 119, section 61. D:\106755214.doc 2002] “TRIAL ON THE MERITS” Printed On: 3/8/2016 381 “there is authority for applying the plain meaning rule even though it produces a harsh or unjust result or a mistaken policy as long as the result is not absurd.”60 Little further elucidation is provided, however, and the overwhelming majority of cases cited in support of that general proposition are civil. But even if it is agreed that the principle applies equally to criminal cases, where does a court draw the line between “mistaken policy” and “absurd results?” What is the difference between the two? Does a result become absurd simply because a court says so? Why is the situation in Wallace an absurd result rather than an accepted statutory “anomaly?” 61 What, finally, is absurd about a defendant in a criminal case, facing a potential loss of liberty of two years if convicted, asking that the clear, plain language of a statute be adhered to? Isn't this a far more reasonable request than the case of a defendant urging, to quote Justice Greaney, a “fanciful or perverse”62 interpretation of a statute? Admittedly, adherence to the statutory requirement of a trial on the merits would likely impose a hardship on officials of public housing authorities and others, including the courts. This would be particularly true if it could be demonstrated persuasively that individuals like the defendant in Wallace default in large numbers when these civil trials are scheduled. But, no such figures documenting court defaults appear in the text or the footnotes of the court's opinion. By the court's own standards, hardship, in these circumstances, is not a factor that should be taken into account. “We cannot interpret a statute so as to avoid injustice or hardship,” the same court has written, “if its language is clear and unambiguous and requires a different construction.”63 It is not uncommon for appellate courts, when scrutinizing statutory language under challenge in criminal cases, to arrive at results which do not appear to serve society's interests or carry out the apparent legislative intent. Yet, there is not, and should not, be a rush to label all these results as absurd. “We have no doubt,” Justice Wilkins wrote in Commonwealth v. Boone, about the escape of the defendant (determined to be a sexually dangerous person and serving a term of from one day to life), “that the law 60. NORMAN J. S INGER , S TATUTES AND S TATUTORY CONSTRUCTION , 2A § 46.01 at 83 (5th ed. 1992). 61. See DaLuz v. Dept. of Correction, 746 N.E.2d 501, 508-09 (Mass. 2001) (stating "[w]e recognize that the statutory language [M ASS. GEN. LAWS ch. 30, §58] appears to creatye an anomaly: a partially disabled employee injured by violence of a prisoner or a patient may recover more assault pay benefits than a totally disabled employee."). 62. Roucoulet, 601 N.E.2d at 473. For further discussion of Roucoulet, see supra notes 35-37 and accompanying text. 63. Rosenbloom v. Kokofsky, 369 N.E.2d 1142, 1144 (Mass. 1977) (citing Milton v. Metro. Dist. Comm’n, 172 N.E.2d 696, 700 (Mass. 1961)). D:\106755214.doc 382 Printed On 3/8/2016: NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 36:2 should provide a penalty for what the defendant did. No statute, or combination of statutes, however, does so.” 64 More recently, the Massachusetts Appeals Court has ruled that handwritten notes containing sexually graphic language and propositions allegedly left (along with money) by an adult in the desk of a fifth-grade student do not constitute “printed material” for purposes of the obscenity statutes.65 Similarly, the Supreme Judicial Court has concluded that the statute66 which criminalizes the act of making annoying telephone calls is not violated when an individual instead sends a series of allegedly annoying facsimile transmissions to a television station.67 Further examples and variations of such results abound in the criminal law, all of which could easily be viewed as absurd since the net effect is that the offensive conduct goes unpunished. But it is not the function of the courts to be writing or re-writing laws or labeling as absurd results which do not conform to the court's way of thinking. “Courts are not at liberty to impose their views of the way things ought to be simply because that's what must have been intended, otherwise no statute, contract or recorded word, no matter how explicit, could be saved from judicial tinkering.”68 IV. It is in the very last sentence, however, of the analysis in Wallace that the court stands its own reasoning upside down and exposes how shallow and disingenuous its position really is. “A sensible construction of the provision in question,” the court writes, “is that no permanent [restraining] order shall be granted until there has been an opportunity for a trial on the merits.”69 Having waited until the end to volunteer that interpretation, the court adds, in a footnote, that “[w]e need not speculate as to the reason for the language in the statute.”70 But the glaring reality is that the court is doing precisely that, speculating, qualifying, “tinkering” with the legislative language. Putting it another way, the inescapable conclusion is that, despite its silence on the subject, the court indeed does find ambiguous the phrase “trial on the merits” in Chapter 121B, section 32F. To achieve its desired objective, the court cannot bring itself to admit this ambiguity. 64. Boone, 477 N.E.2d at 1029. 65. See Commonwealth v. O'Keefe, 723 N.E.2d 1000, 1005 (Mass. App. Ct. 2000). 66. 67. 68. 69. 70. M ASS. GEN. LAWS ch. 269, § 14A (1998). See Commonwealth v. Richards, 690 N.E.2d 419 (Mass. 1998). Kilpatrick v. Superior Court of Arizona, 466 P.2d 18, 27 (1970). Wallace, 730 N.E.2d at 278 (emphasis in original). Id. at 278 n.3. D:\106755214.doc 2002] “TRIAL ON THE MERITS” Printed On: 3/8/2016 383 When there is ambiguity in the language of a penal statute, the defendant by a long, courageous tradition is entitled to the benefit of that ambiguity. This court, however, lacks the courage and intellectual honesty to confer on him that benefit. Even more egregious, the court in this shattering conclusion to its analysis violates bedrock principles of judicial and legislative separation of powers. Only four years earlier, the same court practically boasted of its ability to recognize the limits of its authority by quoting strong language from its earlier cases: “We have traditionally and consistently declined to trespass on legislative territory in deference to the time tested wisdom of the separation of powers as expressed in art. XXX of the Declaration of Rights of the Constitution of Massachusetts even when it appeared that a highly desirable and just result might thus be achieved.”71 Suggesting or implying that the legislature really meant an “opportunity” for a trial on the merits is more than an innocent “trespass on legislative territory.” “We are not permitted to add words to a statute that ‘the Legislature did not see fit to put there,’”72 the same court has spoken. “We must construe the statutes as they are written.” 73 The real, practical difference between trial on the merits and an “opportunity” for trial on the merits is not a subtle nuance. It is a difference in kind, not in degree, a wholesale revamping of the statute, a diminution from statutory insistence on the real thing to a mere “opportunity” for the real thing. There is not a whisper, a hint in Chapter 121B, section 32F, that that is what the legislature intended. In Commonwealth v. Smith,74 a very different but instructive case, the Massachusetts Appeals Court agreed with the prosecution that “the defendant's conduct [digital penetration and oral intercourse with his elevenyear-old daughter], if true, is shocking and abhorrent.”75 Yet, the court affirmed the defendant's motion to dismiss the two indictments charging incest (additional indictments charged indecent assault and battery and assault and battery) on the grounds that the defendant's alleged acts did not constitute “sexual intercourse” within the meaning and purview of Chapter 272, section 17. “We have no right,” Justice Smith wrote, “to read into the incest statute ‘a provision which the legislature did not see fit to put there. . . .’ To do so would amount to judicial legislation, which is 71. Pielech v. Massasoit Greyhound, Inc., 668 N.E.2d 1298, 1302 (Mass. 1996) (citations omitted). 72. Commonwealth v. Russ R., 744 N.E.2d 39, 43 (Mass. 2001) (citations omi tted). 73. Brennan v. Election Comm’rs of Boston, 39 N.E.2d 636, 638 (Mass. 1942). 74. 710 N.E.2d 1003 (Mass. App. Ct. 1999). 75. Id. at 1005. D:\106755214.doc 384 Printed On 3/8/2016: NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW [Vol. 36:2 forbidden by Article 30 of the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights.” 76 By urging that the legislature really meant an “opportunity” for trial on the merits and not an actual trial on the merits in Chapter 121B, section 32F, the court in Wallace for all practical purposes added to the statute “a provision which the Legislature did not see fit to put there.” 77 That interpretation may be a sensible one, in the eyes of many, but the crucial language needed to support that interpretation is altogether missing. Moreover, there are other, equally sensible interpretations of the statute, as written. Statutory insistence on a trial on the merits may convey, for example, a legislative disdain for permanent restraining orders. It is just as plausible to assume that the legislature was expressing a preference that permanent restraining orders be issued only after all parties have had their day in court. Far from being a careful, thoughtful analysis, the decision in Wallace is the judicial equivalent of a “quick fix.” It is a triumph of political correctness and expediency over the rights of a criminal defendant to the orderly process of law. It represents not only judicial activism running amuck and trampling over the explicit wishes of the legislature but a cavalier disregard for the sanctity of the English language. It is an erosion of individual rights that society in the long run can ill afford. 76. Id. at 1006 (citations omitted). 77. Id. (citing King v. Viscoloid Co., 106 N.E. 988, 989 (Mass. 1914)).