Ginger's Oration - The American Legion | Department of

advertisement

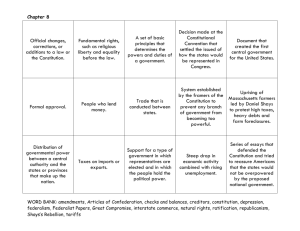

OUR CONSTITUTION: BORN IN CONFLICT, NURTURED BY DEBATE Screams of anguished men pierced the clouds of gun smoke. The acrid fog burned eyes and made it nearly impossible to breathe. Through the din of battle, the ominous whistle of a cannonball forewarned more destruction. The lethal missile thudded dully and tortured cries rang out. Then came the hysterical cry, “Retreat!” Men hailed as the great founders of America are Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. With many others, they labored to craft the United States Constitution. But there is one man whom few will recognize as a contributor to this great document. His name was Daniel Shays, and few events had a greater impact on the Constitution than his rebellion. The Articles of Confederation had been ratified as America’s system of government at the end of the Revolutionary War. Six years later, a storm of discontent was about to strike. The war with England had created massive debts. Because the national government had no power to levy taxes and repay the debt, the states unloaded it on the ordinary citizens. Farmers, and laymen. The very same soldiers who had risked their lives fighting for America’s freedom. If taxes could not be paid, a man could be thrown into debtor’s prison or lose his property. The precious right to vote was directly tied to property ownership--therefore, the very rights they had fought for were being threatened. Daniel Shays, a veteran himself, mustered the loyalty of other farmers like him to aid in his rebellion against the government--a rebellion that would change history. George Washington and Samuel Adams were well aware of Shays’ Rebellion. With anxious eyes, they watched it unfold. It led them to question the wisdom of the new system of government they had ratified six years before. America had scarcely emerged from war. Were they so soon to face more deadly conflict? Shays’ rebellion climaxed on February 3rd, 1787. The farmers and laborers marched on a government arsenal and were met with trained, defending militia. Suddenly, without warning, the militia fired cannonballs into the ranks of farmers, killing four and wounding twenty. Shays’ men were stunned, shaken. Unable to believe that their neighbors and fellow veterans had fired on them, they retreated. Facing charges of treason, Daniel Shays fled. The Rebellion was a failure. But it forced the Founding Fathers to open their eyes to their own failures; chiefly, the Articles of Confederation. The Founders had lived under the tyranny of the English monarchs. They had been determined that no government should have a power of that magnitude in America. In their zeal to purge the colonies of tyranny, the delicate balance of power had been thrown to the other extreme: anarchy. The Articles of Confederation made America little more than that: a confederation of thirteen miniature countries, held together by little more than their name. The national government was crippled and weak. Something had to be done. The Founders could no longer deny that fact. Calling for a convention, they requested that each state send a representative. The conflict of Shays’ Rebellion gave birth to the Constitutional Convention. Many delegates came to Philadelphia that late spring of 1787 expecting to merely revise the Articles of Confederation, or perhaps do some routine maintenance work. But James Madison came with an entirely different agenda in mind. Labeled the Virginia Plan, after his home state, it would completely transform the American system of government if adopted. With papers in his hand, a plan in his brilliant mind, and a fierce passion in his heart, Madison arrived, planning to proffer his ideas to the convention. The mere thought of many long months of tedious debate was exhausting. But the delegates realized that the Articles of Confederation were, at best, inadequate. As Henry Knox of Massachusetts declared, “Our present Federal Government is a name, a shadow, without power or effect.” America had been birthed from conflict, and now it would have to be perfected by nurturing debate. The delegates readied themselves for more deliberations. After months of grueling discussion, every wrinkle was ironed and every weakness was fortified. The Constitution was as near to perfection as imperfect men could possibly render it. Conflict nd debate had been the means to hone and refine America’s very backbone. The result of their labor was a document that still binds America over two centuries later. We the people. The simplicity and elegance of the opening words to the United States Constitution are unmatched. They illustrate the sacred honor and responsibility that are given to every American. The Constitution’s Preamble gives the reasons for its very existence; first of all, to form a “more perfect” union. The signers of the Constitution acknowledged that they were not perfect men, and could therefore not create a perfect government. But they were resolved to “establish justice, ensure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense," and “promote the general welfare." Though the 1905 court case Jacobson versus Massachusetts declared that the Preamble gives no power to the federal government, it still offers great insight into the Founders’ intent. Finally, the Founders wrote that the Constitution was formed to “secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” Their goal was not just to grant the blessings of liberty to American citizens, but to secure them for all future generations. Our blessings of liberty have been challenged many times, but the enduring strength of our Constitution has been a stronghold to which America clings through our darkest times. So after weeks of rigorous debate, the delegates of the Convention crafted a new system of government. This revolutionary idea would be characterized by three branches of government: legislative, executive, and judicial. Debate and healthy conflict are two key mechanisms that would nurture America, and they are prominent in all three articles. The specifics of these branches are outlined in Articles One, Two, and Three. Article One deals specifically with the legislative branch. This was the most divisive article to be debated during the entirety of the Convention. It drew a proverbial “line in the sand:” small states on one side, large states on the other. The small states wanted equal representation, as suggested in the New Jersey Plan. The larger states disputed that James Madison’s Virginia Plan should be followed, which called for representation proportionate to population. At last, a truce was made: the Great Compromise. Rather than having one legislative body, the delegates agreed to incorporate both ideas. The Senate would be elected equally amongst states; the House of Representatives--proportionally. Article Two institutes the Executive Branch, with the President at its head. Far from being a king or ruler, the President’s powers are limited, though he does have the ability to act quickly when necessary, such as during war. Next is Article Three, which deals with the Judicial Branch. The court system was another area which the delegates knew they would have to handle cautiously. Many of them had already witnessed the corrupt judges and rampant discrimination in the British courts. The Third Article specifically establishes the Supreme Court but allows for “such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” One of the most important provisions under Article Five gives instructions for the amendment process. Under the Articles of Confederation, change was virtually impossible. The Founders were humble enough in their experiment to acknowledge that changes would have to be made. But they were confident enough in their masterpiece to know that change should not be easy. They ensured that change would come with conflict and debate to make certain that it would come only when desperately needed. Despite the fact that over two-thousand amendments have been proposed, only twenty-seven have been ratified to date. The Constitutional Convention was one of the most challenging events in American history. The excruciating debate that occurred in its duration is legendary. As is evidenced by Daniel Shays’ rebellion, conflict can result in good. The demanding debate of the Convention served to refine the Constitution. Conflict made certain that it was strong enough to support a country. The United States was birthed from conflict. It has endured to this day because of nurturing debate. Conflict ensures that every issue, every bill, every candidate is examined and scrutinized …and that the final result is truly the best for our country. Born in rigorous debate and nurtured by healthy conflict, our Constitution continues to preserve the United States as the land of liberty and justice for all. Ginger Macfarlan 2008 American Legion Oratorical Contest 1st place, Department of Arkansas 2nd place, National