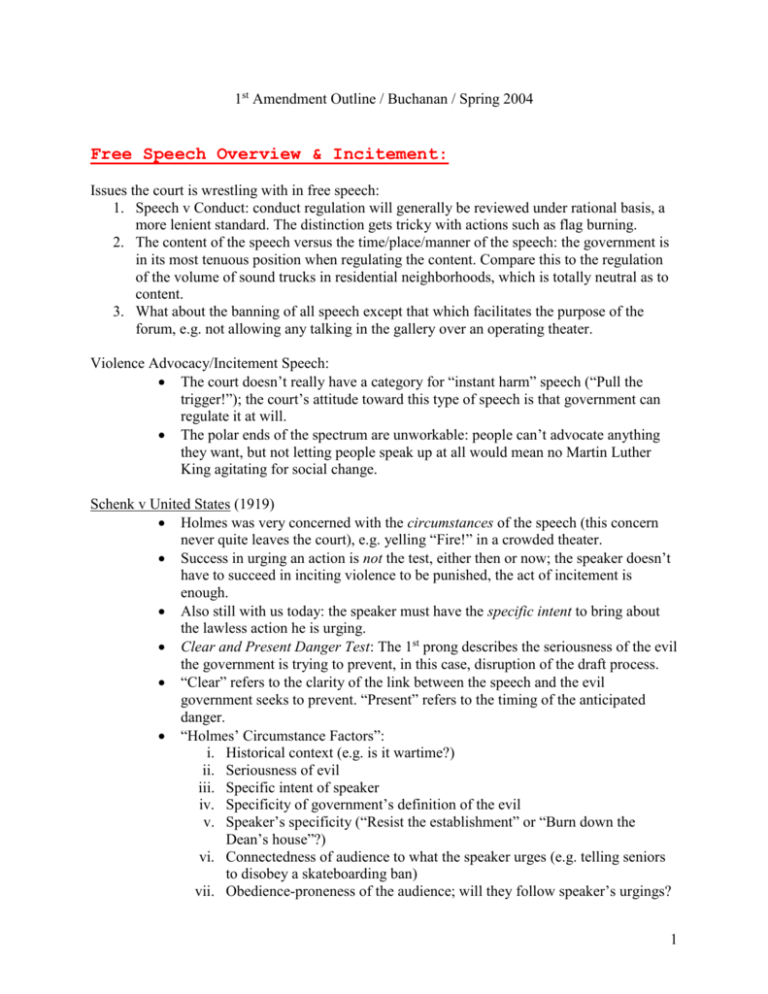

Carter's First Amendment Outline

advertisement