Healthcare labour market in the emerging market economies: A

advertisement

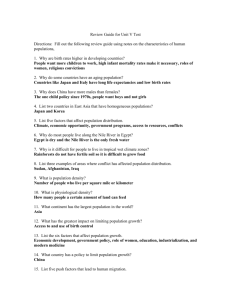

Healthcare labour market in the emerging market economies: A literature review Manisha Nair Premila Webster Abstract Background: Currently there is an increased demand for human resources which has led to the growth of the healthcare labour market. The emerging market economies (EME), such as India and Philippines are the major exporters of health professionals to the industrialised countries such as UK, US, Canada and Australia. The aim of this study is to identify the issues related to the healthcare labour market and find evidence of successful national and international measures to address these issues. Methodology: Review of published literature of last 10 years. Results: The major issues of the healthcare labour market are – migration and shortage of health workers. Several innovative approaches have been used in EME to control migration and address the shortage of health professionals. ii Acknowledgements We are grateful to Professor Harold Jaffe, Dr Kenneth Fleming and Mr. Ian Scott for their invaluable insights and guidance during this literature review. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................................. 1 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................................... 1 RESULTS ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. PATTERNS OF MIGRATION .......................................................................................................................... 2 2. REASONS FOR MIGRATION .......................................................................................................................... 3 a. Employment opportunities .................................................................................................................... 4 b. Wages and work environment ............................................................................................................... 4 3. ROLE OF MEDICAL EDUCATION IN MIGRATION OF HEALTH PROFESSIONALS ............................................... 4 4. GROWING DEMANDS IN HIGH INCOME COUNTRIES...................................................................................... 4 5. FAVOURABLE COUNTRY POLICIES ON FINANCIAL REMITTANCES BY MIGRANT WORKERS ........................... 5 6. SHORTAGE OF HEALTHCARE WORKERS ...................................................................................................... 5 ARGUMENTS IN FAVOUR OF HEALTH WORKFORCE MIGRATION ............................................. 6 POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS ................................................................................................................................ 6 CONCLUSION................................................................................................................................................. 7 APPENDIX-1 .................................................................................................................................................... 8 APPENDIX-2 .................................................................................................................................................... 9 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................................... 12 iv v Background The global healthcare labour market comprises of 59.2 million health workers [3]. The biggest supplier of physicians to the world is India [4-6] and Philippines is the largest supplier of nurses [5, 7]. Other major exporters among the emerging market economies (EME) are China, Mexico, Malaysia, Colombia, Egypt and Pakistan [5, 7-11]. The largest importers are New Zealand, USA, UK, Canada and Australia [5, 7]. Hagoplan et al. ([12]) showed that more than 770,000 (approximately 23%) doctors licensed to work in the USA in 2002 were imported from other countries. Poland, South Africa and Chile export as well as import nurses from the global healthcare labour market [13]. The labour market tries to reach equilibrium by balancing the demand and supply which mainly occurs through migration of health workers [1, 2]. The aims of this literature review are to: (i) identify issues related to the healthcare labour market in the EME (ii) “Health workers are people engaged in actions whose find evidence of successful national and primary intent is to international measures to address these issues. enhance health” [1] Methodology This review is through a systematic search of literature published in last ten years. Studies and reviews that focus exclusively on healthcare labour markets are included. Though the aim of the study is to review the healthcare labour market in EME, a few examples have been drawn from studies conducted in high-income and low-income countries as research conducted in EME are limited. Studies conducted in these countries also contribute to gain an understanding of the factors that ‘pull’ health professionals to high-income countries Results There is a dearth of good quality research on healthcare labour market, especially in the EME [14]. The existing research publications and reviews indicate two major issues related to the healthcare labour market – (i) migration and (ii) shortage of health workers. In the context of these issues it is important to understand the patterns of migration and its causes, and the impacts of health worker shortage. 1 1. Patterns of migration Migration of heath workers both within country and across borders is a well recognised problem in the health care sector in both developing and developed countries. A study undertaken in 1972 by WHO showed that about 6% of the doctors and 5% of the nurses were living outside their home countries[15]. Pacific island and Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) have the highest rates of migration (about 13%), followed by Latin America and Caribbean islands (about 11%) and the Middle East and North Africa (about 10%) [3]. The direction of movement of health professionals within countries is from rural to urban [3] and from public sectors to private and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO) [16], and across countries is south to north [3, 15, 17]. However globalisation has made “brain drain” multidirectional instead of unilateral and the term “brain circulation” appears to replace “brain drain” [3]. For example many health professionals from Canada migrate to the US and the vacancies left behind in Canada are filled by health professionals from India, Philippines, South Africa and other low and middle income countries [3]. Another form of “brain drain” is the “internal brain drain” which causes the health workers to move from public sectors to private sectors, NGOs and to research within the same country [18, 19]. NGOs and humanitarian agencies mostly implement vertical programmes that require high intensity and accelerated performance. Human resource and time are the major determinants for their success. Hence they often adopt shortcuts by hiring efficient health workers from the public health system through generous remuneration [16, Migration is an “individual, spontaneous and voluntary act that is 18]. Studies have shown that more than 80% of nurses in motivated by the SSA have left their government jobs to join NGOs and the perceived net gain of private sector [18], further weakening the health system migrating”[2] already devastated by HIV/AIDS [3, 16]. In recent years a new pattern of migration is becoming prevalent. In Philippines many doctors are re-training as nurses owing to the high international demand for nurses [20] and in China local doctors who are unable to compete in the growing market for physicians trained abroad are shifting to research and jobs in the pharmaceutical companies [21, 22]. The United Nations defines “brain drain” as a one-way movement of highly skilled people from developing countries to developed countries that exclusively benefits the industrialised (host) world. 2 Migration not only has implications on health but also on the economy of the source country [3]. Countries spend a vast amount of money to train their doctors and nurses and often the brightest migrate, and subsequently to fill the gaps left behind, these countries hire consultants from high-income countries [3]. It is estimated that low income countries lose approximately US$500 million annually [12]. On the other hand recipient countries profit because by hiring personnel trained abroad, they do not invest on training these health professionals (known as free-riding) [12]. While Ghana lost more than $US60 million in about 50 years by exporting health workers, UK had saved about £103 million in training health workers over the same period by importing from Ghana [23]. 2. Reasons for migration Migration is an “individual, spontaneous and voluntary act that is motivated by the perceived net gain of migrating”[2]. However it may not be always favourable as many immigrants are underutilised in the recipient country leading to “brain waste” [24]. Studies conducted in several EME such as India, Philippines, Pakistan, Peru and South Africa identified a number of “push and pull” factors for migration of health professionals [12, 25-27]. Push and pull factors The most common factors prevalent for more than sixty years that potentiate migration have been described as the external “pull” and the internal “push” factors (table-1) [6, 28, 29]. These factors have become even more powerful in the backdrop of globalisation and free market economy [6]. Table 1: Push and pull factors Push factors i. Low employment opportunities [15, 28] Pull factors i. High employment opportunities due to shortage of health staff in the destination countries [15, 17, 30] ii. Low wages [3, 16] and poor work environment in home country [3, 15, 17] ii. Higher wage, Filipino nurses earn about twenty times more in the United States than in Philippines [17] iii. Lack of professional development and specialist training especially in advanced iii. Proximity and family links in destination countries [3, 10] medical technologies [3, 15, 17, 30] iv. Political instability and poor socioeconomic conditions [3, 10, 28] 3 a. Employment opportunities There is an increased rate of unemployment among health professionals due to the high annual turnover of doctors and nurses from the growing number of public and private medical schools [10, 15]. In addition, the structural adjustment policies (of the World Bank) adopted by most EME resulted in reduction of jobs and inadequate investment in the healthcare sector [17, 31]. b. Wages and work environment Studies in different countries have emphasised one major factor, “wage” that acts as both push and pull factor [3, 10, 16, 32-34]. Health professionals who do not have proper work environments or are victims of bureaucracy and politics in the home country often go out in search of opportunities to other countries [3, 32-34]. The level of stress due to high responsibility and poor compensation has led to extensive mental and physical exhaustion among young nurses in China [35]. Two studies conducted on nurses in India and Philippines [25] and on doctors in South Africa [12] and another study conducted in Jordan and Georgia in 2004 [36], have identified better wage, job opportunity and work environment as the majors reasons for migration. 3. Role of medical education in migration of health professionals While most studies have focused on the differences in the organisation and salary or remuneration structures as important correlates for migration of highly skilled professionals [17, 37], the structure of the medical education system of the source countries has not received adequate attention. The three main factors that influence this issue are [1, 10]: Increasing numbers of medical schools Quality of medical training Gap between health needs and medical education This is covered in the paper “Education and training for health professionals in the emerging market economies: A literature review” 4. Growing demands in high income countries Most developed countries such as the US, Canada, Australia, and countries in Western Europe are undergoing demographic transition which has started to have its impact on the work force. These countries have an ageing population of doctors and nurses [3, 33]. The current policies of investment in education of health professionals in these countries are insufficient to meet the demands of their growing healthcare market [3, 38, 39] so they try to meet the demands by recruiting health professionals from resource poor countries and from the EMC [3, 38]. 4 5. Favourable country policies on financial remittances by migrant workers EME like Philippines, Turkey and Mexico have developed policies for migrant health professionals to remit money to the country in the form of tax [3, 13]. The growing number of nursing schools in Philippines produce a huge workforce and its government encourages migration especially to collect remittances irrespective of the fact that this is crippling the country’s own health system [13, 20]. Two immediate advantages are seen by these countries, while the first one is explicit, “remittances”, the second is implicit, “ it does not have to create job opportunities for the growing number of health professionals” [20, 28]. 6. Shortage of healthcare workers Globally there is a shortage of 2.4 million physicians, nurses and midwives and 1.9 million pharmacists and other para-medical workers [1, 3]. WHO estimates, the basic healthcare system of 57 low and middle income countries is affected by shortage of human resources [1, 3]. The health systems of 36 countries in SSA have reached a crisis situation due to combination of two factors, brain drain and HIV/AIDS [3]. These are also countries with high rates of maternal, infant and child mortality and shortage of health providers especially for the rural and underserved population [3]. A similar crisis is seen in Mexico after its North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with USA [9]. Migration of health professionals has led to two types of discrepancies between health needs and healthcare workers, the first is within country (urban-rural, public-private or government healthcare sector-private sector) and the second between countries [40]. Though the number of medical and nursing schools is growing in the EME producing a substantial number of health professionals, the ratio of health professional to population in rural areas is grossly inadequate [8, 41]. India produces about 27,000 medical graduates every year and more than 75% of these work in cities whereas about 70% of the patients are from rural areas [42]. Major reason for this is better living conditions, facilities and opportunities in cities than in villages [6]. This has resulted in inequity of health services and the disproportionate distribution of the health workforce between urban and rural areas [34]. Another discrepancy commonly visible in the growing markets like India, Thailand and China is the public-private discrepancy. In the free market economy , with the growth of medical tourism there is a sudden upsurge of private and multinational hospitals [34, 43]. To compete for status and quality these hospitals hire the best specialists from within the country, thereby increasing the internal brain drain [34, 42, 43]. Due to lack of insurance and high out-of-pocket expenditure, the general population cannot afford these private hospitals [42]. They are 5 dependent on the public hospitals for their health needs which do not have adequate human and technical resources resulting in a huge unmet need [42]. The biggest irony is the inverse relationship between disease burden and density of health workers seen in most of the WHO regions (Table-2). Though Africa has a large share of the disease burden (24%), the number of health workers available is 2.3 per 1000 population, while in the Americas the fraction of global disease burden is 10% and there are 24.8 health workers per 1000 population [1, 3]. Table-2: Discrepancies between heath needs and healthcare workers WHO regions Disease burden (as fraction of Density of health workers (per the global disease burden) 1000 population) Africa 24% 2.3 Eastern Mediterranean 10% 4.0 South East Asia 29% 4.3 Western Pacific 17% 5.8 Europe 10% 18.9 Americas 10% 24.8 Source: Working together for health: World health report 2006 (WHO) [1] Arguments in favour of health workforce migration While the general consensus is that, migration of health workforce is detrimental for the health systems and health of population, there are some who consider it favourable. While the NGO pull factor has led to unequal distribution of human resource, it has also prevented cross country migration [16]. Most NGOs and private sectors work closely with governments especially in the EME as a result of liberalisation of the economy. This could be a win-win situation for both health professionals (better remuneration and work environment) and the nation (preventing external brain drain) [16]. Another question that needs to be answered is whether emigration control is the panacea for health systems. Studies have shown factors such as non availability of technical resources, logistics and infrastructure to be the primary reasons for the failure of public healthcare system [44]. There are many unemployed nurses in South Africa and India, despite being among the major exporters [44]. . Possible solutions The first step to resolve the problem of migration is to measure the problem through regular updating of databases of health workers for all countries [3]. Measures to control migration 6 should be country specific and designed in accordance with the push and pull factors existing in the donor and recipient countries respectively. Measures taken by donor countries to mitigate the push factors include (See appendix 2 for more details): NGO code of conduct To control the internal brain drain caused by the movement of government health workers to NGOs, the “NGO code of conduct” was launched in May, 2008 in Washington DC with more than 25 signatories [45]. better wages and work environment [16] need based medical and nursing education [14] improved quality of health education and opportunities for professional development [14] compensation for brain drain [23, 46] retaining health workers in rural areas [47]. Other examples of innovative measures taken to combat shortage of health workers found in the literature include: ‘task shifting’ i.e. training community workers and paramedics to provide basic healthcare for disease prevention and progression [3, 48]. encouraging ‘lost talent’ from host countries to return for short term assignments or hold concurrent positions at home and abroad to aid research and development in the host country [21, 49]. In addition, a “Global Code of Practice” was adopted by the executive board of WHO to address the migration of health workers in January 2009 [23]. Conclusion Migration is a human right but its unidirectional pattern has caused concern especially due to its adverse impact on the healthcare systems. Several national and international commitments have been made, but the basic requirement is to implement the plans through coordinated efforts by governments, development partners, NGOs, civil societies, private sector and the academic world [50]. Concurrent with such efforts is the requirement of data and research in EME to show trends and patterns of migration, and understand the issues in the healthcare labour market. 7 Appendix 1 Search engines/databases used Scopus, Eldis, Pubmed, Popline and Google scholar Key words used Migration, “health workers”, “health professionals”, immigration, emigration, “shortage health workers”, “task shifting”, labour, “labour market”, “healthcare market”. 8 Appendix 2 Examples of successful interventions/policies 1. Measures taken by donor countries to mitigate the push factors a. NGO code of conduct To control the internal brain drain caused by the movement of government health workers to NGOs, the “NGO code of conduct” was launched in May, 2008 in Washington DC with more than 25 signatories [45]. The objectives of this code of conduct are “to provide a framework of good practice and discourage hiring of health workers from the struggling public health systems” [45]. Further it urges the NGOs to replenish the loss by supporting training and capacity building of workers in the health systems [45]. b. Better wages and work environment While it is easy to blame the NGOs and private sectors for paying high wages and providing better work environment, it is difficult to address the root cause of the problem [16]. In United Kingdom, it is prestigious for doctors and nurses to work for the government [16]. This prestige can be linked to decent remuneration, pension and opportunity for professional growth [16]. A study in Malawi showed that on increasing the remuneration of health professionals in the government sector, there was a reversal of the brain drain from NGOs and private sector to the public healthcare systems [16]. A study conducted by Vujicic et al. [51] analysed the wage difference between the source countries in Africa and the recipient countries and have found a huge gap which cannot be narrowed by a small increase in the salary of the health professionals in these source countries [51]. They suggest non-wage instruments such as improved working and living conditions to be more effective in controlling migration in such countries [51]. Partners in Health in Haiti has been able to retain health professionals in rural areas by providing them a suitable work environment with appropriate resources to treat patients [3]. Apart from this, hardship allowance paid to health workers in rural areas of Zambia has been favourable in decreasing the shortage in remote rural areas [3] c. Need based medical and nursing education The education curriculum of most countries needs updating to focus on the healthcare needs of the population [3]. The focus is shifting from a specialist to generalist approach as most of these EME are undergoing reforms in their health systems [14]. This will decrease the mismatch between training and employment opportunities and will also help retain the health workforce in rural areas [3, 14]. 9 d. Improved quality of health education and opportunities for professional development Apart from financial incentives, another incentive that is seen to work effectively in Ghana, Uganda and South Africa is the provision for professional development [3]. Health professionals and students from local areas are awarded scholarships to undergo training in developed countries provided that they agree to return and work in rural and underserved areas of the country [3, 52]. e. Compensation for brain drain This radical measure is currently being discussed in several forums and suggested by many authors. It is suggested that recipient countries repay the donor countries through financial and technical support to their health systems [3, 23]. Compensation is basically to mitigate the freeride and introduce fair trade in the healthcare labour market [23, 46]. f. Retaining health workers in rural areas A study conducted in New Mexico identified financial incentives and opportunities for professional development and community based training in rural areas to be important factors to increase recruitment and retention in rural areas [47]. However, only one study in EME, conducted in South Africa tried to identify factors that will help retain doctors in remote rural areas. The findings are comparable to that of New Mexico, however the doctors in South Africa also demanded better hospital infrastructure and technology and proper accommodation in rural areas [53]. 2. Innovative measures taken to combat shortage of health workers Task shifting is the current policy of choice in many countries in Africa and South Asia. Community workers and paramedics are trained to provide basic healthcare for disease prevention and progression and in many cases they act as the first contact point for patients [3, 48]. Doctors and nurses are mainly reserved for special and advanced clinical care. For example the ASHAs (Accredited Social Health Activists) of National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in India provide effective maternal and newborn care at community levels, normal deliveries being conducted by nurses in sub-centres and Primary Health Centres (PHCs), while trained obstetricians manage only the few complex cases [54]. This has helped to deal with the shortage of obstetricians in rural areas. Another example is Lusikisiki in South Africa, where pharmacy assistants provide the basic care to HIV/AIDS patients, nurses prescribe anti-retroviral drugs and only the complex and advanced AIDS cases are dealt with by the physician [3]. Thailand has tackled its acute internal brain drain (from rural government hospitals to urban private hospitals) through training of rural health personnel in health centres in basic medical care [55]. 10 3. Innovative examples of ‘brain circulation’ An innovative approach taken by China since 2001 is “brain circulation”. Chinese government is encouraging their ‘lost talent’ to return for short term assignments or hold concurrent positions in China and abroad to aid research and development in the country [21, 49]. A similar trend is seen among the Indian emigrants [56]. Perhaps affinities towards their culture, an emerging economy and provision from governments are the reasons that these two countries share for the growing trend of “brain circulation” [21, 56]. The EME can particularly benefit from this triangular flow of talent, however the challenge is to find successful measures to attract them [56]. 4. Measures at the global level Following the World Health Report, 2006, “Working together for health” which highlighted the critical issue of global health worker crises, WHO formed the Global Health Workforce Alliance (GHWA) [57]. GHWA has been working towards its vision of resolving the health workforce crisis through integrated efforts and global partnerships [33]. It convened the first ever Global Forum on Human Resources for Health in Kampala, Uganda in March 2008 wherein the Kampala declaration was signed [50]. It was declared that country-specific plans will be made to strengthen the health workforce and donor countries such as UK, USA and Japan will support training new health workers [50]. Six months later in September 2008, at a United Nations highlevel meeting on the MDGs it was resolved that the final push for the MDGs would be through addressing the health workforce crisis and a taskforce on innovative financing for health was launched [50]. In January 2009, a “Global Code of Practice” was adopted by the executive board of WHO to address the migration of health workers [23]. 11 References 1. World Health Organisation. Working together for health: World health report 2006. World Health Organisation, Geneva; 2006. 2. Zurn P. Imbalance in the health workforce. Human Resources for Health [NLM - MEDLINE]. 2004;2. 3. Serour GI. Healthcare workers and the brain drain. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2009;106(2):175-8. 4. Supe A, Burdick WP. Challenges and issues in medical education in India. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2006;81(12):1076-80. 5. Migration of health professionals: OECD; 2008. Report No.: CESifo DICE Report 1/2008 Contract No.: Document Number|. 6. Adkoli BV. Migration of health workers: Perspectives from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Regional Health Forum. 2006;10(1):49-58. 7. Mullan F. The Metrics of the Physician Brain Drain. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17 %U http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/353/17/1810 %8 October 27, 2005):1810-8. 8. Talati JJ, Pappas G. Migration, medical education, and health care: A view from Pakistan. Academic Medicine. 2006;81(12 SUPPL.):S55-S62. 9. Hildebrandt N, Mckenzie DJ. The effects of migration on child health in Mexico. ECONOMIA. 2005:257-89. 10. Astor A, Akhtar T, Matallana MA, Muthuswamy V, Olowu FA, Tallo V, et al. Physician migration: Views from professionals in Colombia, Nigeria, India, Pakistan and the Philippines. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61(12):2492-500. 11. Rosselli D, Otero A, Maza G. Colombian physician brain drain [6]. Medical Education. 2001;35(8):809-10. 12. Marlene MB, Gina J, Louis AH, Magdalena CS. Reasons for Doctor Migration from South Africa. 2009 %9 reasons doctor migration South Africa %! Reasons for Doctor Migration from South Africa; 2009. 13. Brush BL, Sochalski J. International Nurse Migration: Lessons From the Philippines. Policy Politics Nursing Practice. 2007;8(1 %U http://ppn.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/8/1/37 %8 February 1, 2007):37-46. 14. Chopra M, Munro S, Lavis JN, Vist G, Bennett S. Effects of policy options for human resources for health: an analysis of systematic reviews. The Lancet. 2008;371(9613):668-74. 15. Stilwell B, Diallo K, Zurn P, Vujicic M, Adams O, Dal Poz M. Migration of health-care workers from developing countries: strategic approaches to its management. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82:595-600. 16. Zachariah R, Ford N, Philips M, Draguez B, Harries AD. Reply to: What about health system strengthening and internal brain drain? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009;103(5):534-5. 17. Bach DS. International migration of health workers: Labour and social issues. SECTORAL ACTIVITIES PROGRAMME. In press 2003. 18. Larsson EC, Atkins S, Chopra M, Ekström AM. What about health system strengthening and the internal brain drain? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009;103(5):533-4. 19. Kassaye KD. Local brain drain. The Lancet. 2006 2006/10/6/;368(9542):1153-. 20. Cheng MH. The Philippines' health worker exodus. The Lancet. 2009 2009/1/16/;373(9658):111-2. 21. Zweig D. Competing for talent: China's strategies to reverse the brain drain. International Labour Review. 2006;145(1-2):65-89. 12 22. Ogbu UC, Arah OA. The metrics of the physician brain drain [8]. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(5):528-9. 23. Agwu K, Llewelyn M. Compensation for the brain drain from developing countries. The Lancet. 2009 2009/5/22/;373(9676):1665-6. 24. Carr SC, Inkson K, Thorn K. From global careers to talent flow: Reinterpreting ‘brain drain’. Journal of World Business. 2005;40:386-98. 25. Alonso-Garbayo Ã, Maben J. Internationally recruited nurses from India and the Philippines in the United Kingdom: The decision to emigrate. Human Resources for Health. 2009;7. 26. Nadir Ali S, Farhad K, Marie A, Syeda Kausar A, Rose P. Reasons for migration among medical students from Karachi. Medical Education. 2008;42(1):61-8. 27. Mayta-Tristán P, Dulanto-Pizzorni A, Miranda JJ. Low wages and brain drain: an alert from Peru. The Lancet. 2008;371(9624):1577. 28. Ahmad OB. Managing medical migration from poor countries. BMJ. 2005 July 2, 2005;331(7507):43-5. 29. Donna SK. Push and Pull Factors in International Nurse Migration. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2003;35(2):107-11. 30. Adkoli BV, editor. Migration of Health Workers: Perspectives from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka; 2006. 31. Shafqat S, Zaidi AKM. Pakistani Physicians and the Repatriation Equation. N Engl J Med. 2007 February 1, 2007;356(5):442-3. 32. Willis-Shattuck M, Bidwell P, Thomas S, Wyness L, Blaauw D, Ditlopo P. Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2008;8(247):1-8. 33. Omaswa F. Human resources for global health: time for action is now. The Lancet. 2008 2008/2/29/;371(9613):625-6. 34. Mullan F. Doctors for the world: Indian physician emigration. Health Affairs. 2006;25(2):38093. 35. Siying W, Wei Z, Zhiming W, Mianzhen W, Yajia L. Relationship between burnout and occupational stress among nurses in China. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;59(3):233-9. 36. Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R, Stubblebine P. Determinants and consequences of health worker motivation in hospitals in Jordan and Georgia. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58(2):343-55. 37. Diallo K. Data on the migration of health-care workers: sources, uses, and challenges. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82:601-7. 38. Fox R. An examination of the UK labour market for doctors. Economic Affairs. 2007;27(1):5864. 39. Pond B, McPake B. The health migration crisis: the role of four Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1448–55. 40. Lancet T. The crisis in human resources for health. The Lancet. 2006 2006/4/14/;367(9517):1117-. 41. Homi K. Measuring the shortage of medical practitioners in rural and urban areas in developing countries: a simple framework and simulation exercises with data from India. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2008;23(2):93-105. 42. Mbbs SB. Growth generates health care challenges in booming India. CMAJ. 2008 April 8, 2008;178(8):981-3. 43. Wibulpolprasert S, Pachanee C-a, Pitayarangsarit S, Hempisut P. International service trade and its implications for human resources for health: a case study of Thailand. Human Resources for Health. 2004;2(10):1-12. 44. Development Research Centre on Migration GP. Skilled migration: Healthcare policy options. In: Development Research Centre on Migration GP, editor.; 2006. p. 1-4. 45. Bristol N. NGO code of conduct hopes to stem internal brain drain. The Lancet. 2008 2008/7/4/;371(9631):2162-. 13 46. Mcelmurry BJ, Solheim K, Kishi R, Coffia MA, Woith W, Janepanish P. Ethical concerns in nurse migration. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2006;22(4):226-35. 47. Zina MD, Betsy JV, Betty JS, Margaret LS, Robert LR. Factors in Recruiting and Retaining Health Professionals for Rural Practice. The Journal of Rural Health. 2007;23(1):62-71. 48. The L. Finding solutions to the human resources for health crisis. The Lancet. 2008 2008/2/29/;371(9613):623-. 49. Zweig D, Fung CS, Han D. Redefining the brain drain: China's 'diaspora option'. Science, Technology and Society. 2008;13(1):1-33. 50. Møgedal S, Sheikh M. 2009: a crucial year for progress on the health workforce crisis. The Lancet. 2009 2009/1/30/;373(9660):300-. 51. Vujicic M, Zurn P, Diallo K, Adams O, Dal Poz M. The role of wages in the migration of health care professionals from developing countries. Human Resources for Health. 2004;2. 52. Saravia NG, Miranda JF. Plumbing the brain drain. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82(8):608-15. 53. Kotzee TJ, Couper ID. What interventions do South African qualified doctors think will retain them in rural hospitals of the Limpopo province of South Africa? Rural and remote health [electronic resource]. 2006;6(3):581. 54. Ministry of Health & Family Welfare GoI, New Delhi. National Rural Health Mission [cited 2009 13 September]; Available from: http://mohfw.nic.in/NRHM.htm. 55. Wibulpolprasert S, Pengpaibon P. Integrated strategies to tackle the inequitable distribution of doctors in Thailand: For decades of experience. Human Resources for Health. 2003;1. 56. Tung RL. Brain circulation, diaspora, and international competitiveness. European Management Journal. 2008;26(5):298-304. 57. Chen L, Omaswa F, Mogedal S, Nordstrom A, Wibulpolprasert S, Horton R. The Kampala Forum on working together to overcome the workforce crisis--a call for papers. The Lancet. 2007 2007/8/31/;370(9588):631-2. 14