Analyses reported below estimate the nature of the relationship

advertisement

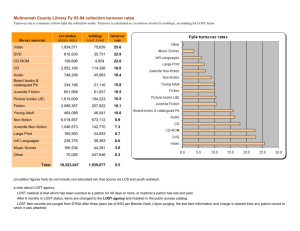

Forecasting Monthly Turnover in BIG COMPANY Call Center Positions: April, 2005 to March, 2006 Overview and Caveats Analyses reported below estimate the nature of the relationship between 1) ABC Consulting assessments and 2) length of subsequent job tenure among recent applicants for call center positions at BIG Company. The forecasts are expected to be accurate to the extent that 1) relationships between ABC Consulting assessments and subsequent job tenure are found and 2) future applicants for call center positions are drawn from the same applicant pool population that past applicants were drawn from. Specifically, using each successful applicant’s assessment score profile, the model forecasts how many days s/he is likely to stay on the job. Forecasts were made regarding how many of the successful applicants hired since June, 2003 will still be employed in the months making up the second and third quarters of 2005 (i.e., April through September, 2005). Median job tenure of those hired between June, 2003 and March, 2005 and who subsequently turned over was 80 days. Figure 1 below shows the job tenure frequency distribution of those who turned over. Visual interpretation of the frequency distributions suggests the highest risk of turnover occurs in the first 120 days (70% turnover within 120 days, while 80% turned over within 180 days or 6 months). Further, forecasted turnover dates for individuals with more than 6 months of job tenure (i.e., hired prior to October 1, 2004) will likely be inaccurate, as causes of turnover after 6 months of employment appear to be fundamentally different from causes of turnover during the first 6 months of employment. For example, while median job tenure was 80 days for those who turned over, those who turned over by failing to return from leave (N = 15) was 179 days and for violations of rules/insubordination (N = 81) was 214 days. Hence, assuming BIG COMPANY is constantly hiring to refill positions as turnover occurs, turnover forecasts beyond 180 days into the future cannot be made with any accuracy from the current data (either because the employees most likely to turnover in October, November, and December of 2005 have not yet been hired or because causes of turnover are more difficult to predict the longer a person spends on the job). Forecasts of future turnover rates in this report are limited to the 6 months occurring between April and September, 2005. Figure 1: Job tenure frequency for those who turned over, June 2003 to February, 2005 0.2 150 100 0.1 50 0 0 100 200 300 400 # of Days on the Job 500 Proportion per Bar # of Incumbents Still on the Job 200 0.0 600 Regardless, some caveats about these predictions must be kept in mind. Forecasts for future months will decrease in accuracy relative to forecasts made on historic data (i.e., the data obtained on successful applicants between June, 2003 and March, 2005 used to estimate the model) if some fundamental changes occur in the nature of the labor market(s) or how BIG Company (or its competition) draws applicants from those markets. Specifically, changes in recruiting activities (by BIG COMPANY or its labor market competitors), changes in applicant demand (by BIG COMPANY or its labor market competitors), changes in applicant supply (quality or quantity), or any other factor that might influence the depth or quality of the applicant pool could cause turnover forecasts to become less accurate. Note, the traditional metric of prediction accuracy for least squares multiple regression is the multiple correlation coefficient RY . X1 X 2 ... X k , where Y is the criterion or dependent variable to be predicted and X1 to Xk are the predictor or independent variables. Unfortunately, RY . X1 X 2 ... X k is greatly influenced (generally reduced) by a number of characteristics of how a study and subsequent analyses were conducted. Use of a personnel selection system in selecting among applicants (i.e., generally selecting those with higher scores) results in reduced variability in X1 through Xk among newly hired applicants because applicants with low values of X1 through Xk were simply not hired. Restriction in range of X1 through Xk causes estimates of RY . X1 X 2 ... X k to be lower than they would have been if the range of X1 through Xk had not been restricted (i.e., if all applicants had been hired with no consideration given to their assessment scores). Portions of the current sample were selected on the basis of scores generated by ABC Consulting solutions, while scores on ABC Consulting solutions were not generated or given consideration in selection of other portions of the sample. Hence, the current data do not permit good estimation of how accurate the model is in predicting future turnover. A conservative estimate of accuracy in turnover prediction comes from an earlier report (Beaty, 2004). The best, most accurate, estimate of prediction accuracy will be reflected in the correlation between the 1) predicted estimates of job tenure ( $y in days) and 2) actual job tenure observed (y) for remaining employees and recruits who are newly hired over the next 6 months. Method Predictors Turnover was predicted using two types of information. The first was derived from items from the ABC Consulting solution administered to applicants for BIG COMPANY call center positions between June 6, 2003 and March 11, 2005. These items are listed below. Each item was accompanied by a 5-point response scale, yielding 47 x 5 = 235 separate response options used as predictors in the current study. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. Being on time for work is not as important as some people say it is. Even when I am very upset, it is easy for me to control my emotions. Having goals and quotas makes work more exciting. Having my telephone calls with clients recorded or having my supervisor listen in wouldn't bother me at all. How many jobs have you held in the last 5 years? How much experience do you have working in a call center (centre)? I am able to maintain a standard work schedule with the same start, stop, break, and lunch times each week. I am comfortable multi-tasking -- such as accessing multiple computer screens, while talking on the phone and answering customer questions. I am known for being committed to my work. I am looking for entry level positions with a great company to 'get my foot in the door'. I can learn many new things in a relatively short period of time. I can usually stay calm, even in stressful situations. I could adhere to a strict work schedule. I do whatever is necessary to improve my chances of advancing beyond my current position. I do whatever it takes to make people happy. I don't enjoy having to make others happy. I easily adapt to changes and new ways of doing things. I enjoy working in a fast-paced environment. I expect repetition in this job; doing the same thing every day wouldn't bother me at all. I have a strong desire to exceed expectations rather than just succeed. I must admit that I often lose my temper. I need some time to adapt to new situations. I would enjoy accepting customer calls throughout the entire day with little opportunity for socializing with my co-workers. I would enjoy receiving job performance feedback from my supervisor on a regular basis. I would enjoy talking to customers on the phone all day. 26. I would enjoy working in a highly structured environment where my breaks and schedules are fixed. 27. I would enjoy working in a job where I constantly had to learn new things. 28. I would like a job where I talk on the phone to customers all day. 29. I would like to attain the highest position in an organization someday. 30. I would not enjoy dealing with customers who are angry or get frustrated easily. 31. I wouldn't mind having my performance monitored very closely. 32. If we asked your last supervisor or teacher, how would he/she rate your ability to meet goals or complete assignments? 33. If we asked your last supervisor or teacher, how would he/she rate your ability to quickly learn large amounts of information? 34. In difficult situations, I can think about a problem calmly. 35. In school and/or at my previous job, I often took it upon myself to learn more than my classmates/coworkers. 36. In school or at work, I usually ask my teacher/supervisor for feedback on my performance. 37. In school or at work, I usually learn new things much faster than others. 38. In stressful situations, I generally remain calm and composed. 39. It takes a lot for someone to hurt my feelings. 40. Other people get on my nerves a lot. 41. People I know would say that I have a lot of patience. 42. People often tell me about their problems and feelings. 43. People say that I am flexible. 44. When given an assignment or goal, I ALWAYS do more than what's expected of me. 45. When someone with authority tells me to do something, I always do it. 46. Why are you interested in this position? 47. Working for a large company is an important part of my career goals. A predictor score was derived by empirically keying the response options.1 Second, seasonal turnover trends had been noted by BIG COMPANY in the past. Hence, the four quarters within a calendar year where dummy coded (i.e., 1 = 1st 3 months of year, 2 = 2nd 3 months of year, etc.). Criterion The primary criterion used in analyses reported below is labeled “job tenure.” It deserves brief mention because it is known to contain a particular kind of inaccuracy. Specifically, all employees will turnover sooner or later due to voluntary (e.g., leaves for a better job elsewhere, promoted internally, retirement, etc.) or involuntary (e.g., fired for cause, laid off, death, etc.) reasons. Simply measuring turnover as a dichotomous variable where 0 = turned over and 1 = not turned over results in loss of information, e.g., it fails to distinguish between those who turned over in their 3rd week and those who turned over in their 3rd year. Job tenure, a simple count of the number of days between date of initial employment 1 Each response option was initially correlated with job tenure for those who had turnover and for all applicants. Predictor scores = sum of correlations between response options selected by each applicant. Predictor scores did not differ meaningfully based on whether they had been derived from 1) applicants who had turned over versus 2) all applicants. The predictor score derived from correlations based on only those applicants who had turned over was used here. and date of turnover, recaptures that lost information while simultaneously injecting a new source of systematic measurement error. The systematic error occurs because most studies of turnover, including this one, use employee samples that include both individuals who have turned over and individuals who have yet to turnover (but who will at some unknown point in the future). The job tenure of those who have turned over is accurately known. The job tenure of those who have yet to turnover cannot be known with certainty. All one knows for sure is that their job tenure will be at least one day longer then the difference in days between the date on which turnover data was gathered and their start date. Hence, while the true job tenure measure Y for these individuals will be the number of days between their hire date and (future) turnover date, a conservative estimate of job tenure for those who have yet to turnover is “Date of data acquisition – Hire date + 1.” This is how the “job tenure” measure was operationalized for analyses reported below.2 Analyses, Results, and Discussion Job tenure was regressed onto 1) the predictor score derived from ABC Consulting assessments and 2) the seasonal dummy variable. When this was done for just those applicants in the sample who had actually turned over, RY X1 X 2 = .13 (p < .01), though the regression coefficient for the season dummy variable was not significantly different from zero. When the same analysis was done on all applicants in the sample (i.e., including those who had yet to turnover),3 RY X1 X 2 = .15 (p < .01) and the season dummy variable became significant. The difference in contribution of the seasonality factor suggests something different was contributing to prediction of applicants decisions to stay on the job versus leave early. Consequently, comparisons were made of the average job tenure associated with each stated “reason for turnover.” Table 1 reports descriptive statistics from this comparison. 2 A separate model was derived regressing job tenure onto predictor variables for just those individuals in the data who had turned over, i.e., on just those individuals on whom we had accurate job tenure data. Predictions made by this model were trivially different from those made by the model estimated on all individuals in the sample, though the smaller sample size (N = 748 versus N = 1348) caused prediction intervals to be wider around those forecasts. 3 Recall, the job tenure measure for those who had yet to turnover was set equal to the number of days between March 13, 2005 and their date of hire. Data was acquired on March 12, 2003, hence this computation implicitly assumes all those still employed were at least still employed the next day. Table 1: Job Tenure by Reason for Turnover Job Tenure Excessive Absences Poor Perform Violation of Rules Failure to Return from Leave Failed Background Check Resigned N Mean Median SD 70 104 74 89 112 86 94 50 81 176 176 102 15 214 169 139 13 18 15 22 646 109 74 97 Recall the median job tenure among all those who turned over was 80 days, with 70% turning over within 120 days. Results reported in Table 1 suggest those who turn over after 120 days do so for substantively different reasons (i.e., Violation of Rules/Insubordination and Failure to Return from Leave) compared to those turning over within the first 4 months on the job. Curiously, interpretation of the significant “season” dummy variable suggests those who have not turned over yet tended to be hired earlier in the year (winter and spring). Combined, these findings suggest those “stayers” who remain on the job or turnover late (> 120 days) on the job do so for substantively different reasons than those who turnover early (< 120 days) on the job. As most turnover occurs within the first 120 days of employment, all forecasts below were made only for those individuals hired in the last 6 months (i.e., since September, 2004). Prediction of turnover for those “stayers” hired prior to September, 2004, cannot be as accurate due to 1) the systematic measurement error contained in their job tenure noted above (i.e., job tenure is necessarily a conservative downside estimate for those who haven’t turned over yet), 2) smaller N, and 3) the apparent fact that different things influence their turnover, causing their response option → turnover relationships to differ from those who turnover within 120 days. Forecasts of future turnover dates for each successful applicant were made from the multiple regression equations reported above. Given the prior conclusion that those who haven’t turned over and/or who turned over after 120 days of job tenure do so for different reasons, it is not surprising that forecasts differed for the two prediction models. Specifically, forecasts made from a model derived from all applicants hired between June, 2003 and March, 2005 yielded an average expected job tenure of 179 days. Forecasts made from a model derived from just those applicants who had turned over during this period yielded an expected average job tenure of 110 days. Unfortunately, we cannot know which of the current employees are likely to be “quick turnovers” (i.e., those who turnover in less than 120 days) versus “stayers” (i.e., those who stay longer than 120 days and, when they do turnover, do so for different reasons).4 Hence, for purposes of prediction, Table 2 presents forecasted turnover frequency for the Note, additional analyses were performed to determine whether “early leaver” versus “stayer” status could be predicted. Significant prediction of this coarse, artificially dichotomized turnover outcome did not occur. 4 next 6 months drawn from 1) a model derived from just those who had turned over (Model A), 2) all applicants hired between June, 2003 and March 11, 2005 (Model b), and 3) an average of the Models A and B. Note, Model A forecasts are particularly low because it predicts most individuals hired since September, 2004, would have turned over some time prior to April 1, 2005. In fact, many did, though because Table 2 only makes forecasts for those who are still employed, they are not included in Table 2’s forecasted future turnover counts. Table 2: Predicted Turnover for New Hires Remaining since September, 2004 Model Model A2 B3 Salt Lake City (N = 13) Average1 Phoenix (N = 45) Average1 Average1 Model Model A2 B3 Greensboro (N = 3) Model Model 2 Model A A2 B3 34 33 10 27 6 4 6 17% 23% 7% 19% 0 0 133% 13% 9% 13% 0 50 12 19 45 5 15 5 May, 2005 25% 8% 13% 31% 0 0 0 11% 33% 11% 0 29 16 4 23 13 6 6 11 June, 2005 14% 11% 3% 16% 0 33% 0 29% 13% 13% 85% 20 19 1 11 9 6 2 July, 2005 10% 13% 1% 8% 0 0 0 20% 0 13% 15% 45 1 21 1 1 14 August, 2005 0 22% 1% 0 15% 33% 0 0 2% 0 31% 0 September, 9 3 1 6 2005 0 0 4% 0 0 2% 0 0 33% 0 0 13% 0 1. Average month of turnover based on average forecasted job tenure of Models A and B. 2. Model A derived from only those individuals who were hired and turned over between June, 2003 and March 12, 2005. 3. Model B derived from all individuals hired between June, 2003 and March 12, 2005. April, 2005 39 19% 17 8% 40 20% 30 15% 2 1% Model Model A2 B3 Ft. Lauderdale (N = 145) Average1 Forecast Period Average1 Predicted # Turning Over if Hired Since 9/1/2004 (N = 206) 17 8% 44 22% 10 5% 1 1% Next, forecasts made in Table 2 were broken split out by location. The last 12 columns of Table 2 contain forecasted turnover frequencies. Table 3 below contains descriptive statistics for those who were both hired and turned over between June, 2003 and March, 2005. Table 3: Descriptive Statistics for Job Tenure by Location N of cases Minimum Maximum Median Mean SD Ft. Lauderdale 449 0 529 77 105.1 93.7 Greensboro 274 0 526 85 119.3 101.5 Phoenix 224 0 478 87 117.0 95.8 Salt Lake City 3 130 298 284 237.3 93.2 Model Model 2 Model A A2 B3 3 23% 10 77% 0 0 0 0 0 3 23% 10 77% 0 0 0 Finally, relationships between recruiting source and job tenure were examined. Table 4 contains job tenure descriptive statistics for each recruiting source. Curiously, Past Employees have the lowest median job tenure (mean job tenure is highly influenced by extreme values in the data, hence, medians are a better index of central tendency). Applicants referred from the Arizona Republic and Yahoo.com where the only source of applicants with median job tenure greater than 100 days for those who had already turned over. AOL and Monster.com had the highest median job tenure for those who had yet to turnover, while the job tenure of their recruits who had turned over was fairly short (65 and 67 days, respectively). Table 4: Job Tenure for First Measure of Recruiting Source1 SOURCE N Minimum Maximum Median Mean SD SOURCE N Minimum Maximum Median Mean SD SOURCE N Minimum Maximum Median Mean SD Research Turned Over 4 18 106 75.5 68.8 41.9 Yet to Turnover 2 138 138 128 138 0 Walk In Turned Over 22 0 350 93.5 113.0 100.8 Yet to Turnover 16 96 537 316.5 302.3 103.2 Internet Turned Over 216 0 529 78.0 114.6 101.2 Job Fair Turned Over 22 17 341 82.5 110.2 91.4 Yet to Turnover 26 19 523 295 288.7 106.3 Yet to Turnover 28 26 544 327 314.0 127.1 Past Employee Turned Over 12 9 158 58.5 62.7 40.9 Yahoo Arizona Republic Turned Over 39 0 310 102 117.6 83.9 Yet to Turnover 164 12 579 313 294.5 126.5 Referral from BIG COMPANY Turned Yet to Over Turnover 129 91 0 12 393 551 78.0 320 103.6 304.0 86.0 133.9 Turned Over 12 29 314 127 150.9 107.3 Yet to Turnover 13 12 397 264 228.8 141.1 Yet to Turnover 15 47 411 229 204.7 124.3 AOL Turned Over 11 26 347 65 139.9 112.8 Yet to Turnover 11 103 425 341 310.0 103.4 Advert. Turned Over 183 0 524 85.0 113.5 02.3 Yet to Turnover 131 19 558 250 247.3 134.2 College Turned Over 12 12 227 96.5 97.1 59.8 Yet to Turnover 8 103 411 337.5 296.4 115.7 Miami Herald Turned Over 16 16 413 96 117.5 95.6 Yet to Turnover 7 47 495 320 265 167.4 SOURCE N Minimum Maximum Median Mean SD 1. Monster Turned Over 61 2 529 67 101.0 108.2 Yet to Turnover 40 26 537 358.5 340.8 121.9 Employment Guide Turned Over 35 0 367 78 96.1 79.9 Yet to Turnover 34 26 523 152 191.9 121.6 Other Career Builder Turned Over 55 4 412 84 112.5 93.5 Yet to Turnover 30 47 523 288 286.0 136.5 Turned Over 94 0 393 78 105.2 94.2 Yet to Turnover 75 12 570 278 260.7 130.0 Note, some of these categories are subsequently broken down into smaller subcategories (e.g. Advertising contains figures reported separately for the Arizona Republic, Miami herald, and Employment Guide). Further, only sources with N > 10 were reported. Future Directions It remains to be seen which Model (or the average of the two) will predict best. One might expect some weighted combination of Model A & B predictions would be preferred. As actual turnover is incurred over the next 6 months, comparisons can be made to determine which Model or weighted/unweighted combination of the models predicts best. In addition, once the preferred forecasting model is identified, BIG COMPANY might want to consider commissioning development of a spreadsheet tool to make ongoing rolling turnover forecasts as new hires occur. One such spreadsheet was developed to make the forecasts contained in Table 2 above. With modifications, this spreadsheet could be used as a Rolling Turnover Forecasts document generated in real time showing BIG COMPANY human resources personnel what the expected turnover frequencies are going to be in the immediate future, helping them make decisions about allocation of recruiting resources, etc. References Beaty, J. (2004, September). Phase 1 Evaluation of New Job-Fit and Cognitive Biodata Assessments for BIG Company Call Centers. ABC Consulting, Inc.