Ricardian Equivalence and Consumption Response to Government

advertisement

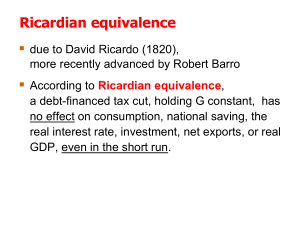

Ricardian Equivalence and Consumption Response to Government Transfers: Behavioral Motives Meet Savers and Spenders in the Real World Wei-Kang Wong1 Abstract This paper uses survey to explore to what extent different behavioral motives might have affected real-world decision makers’ propensity to consume actual one-off government transfers in Singapore and how the appeal of these motives might be related to personal characteristics. JEL Codes: D91, E21, E62, H31 Keywords: Ricardian Equivalence, Mental Accounting, Precautionary Savings, Present Bias, Rule-of-Thumb Consumers 1 Department of Economics, National University of Singapore, AS2, 1 Arts Link, Singapore 117570, Republic of Singapore. Email: ecswong@nus.edu.sg; Phone: (65) 6516-6016; Fax: (65) 6775-2646. I especially thank George Akerlof for encouragement, Jack Knetsch for comments, and Alan Yap for research assistance. I also thank participants at the joint symposium of Yonsei University, Keio University, University of Hong Kong, Fudan University and the National University of Singapore for comments and Yu Zengyang, Chua Thiam Hao, and Kevin Khoo Hng Kiat for their assistance. As the rule of thumb, I should be solely responsible for any remaining errors. 1. Introduction On 17 February 2006, the Singapore government announced a number of oneoff transfers and rebates to its citizens in Financial Year 2006 under the so-called “Progress Package,” with larger transfers to the less well-off.2 The total package amounted to S$2.6 billion, 78% of which were distributed as cash transfers under three different schemes.3 Following the survey studies on price stickiness (Blinder, 1994), wage stickiness (Bewley, 1998) and inflation aversion (Shiller, 1996), this paper uses survey to empirically investigate the extent to which competing behavioral motives might have influenced the consumption and saving decisions of real-world decision makers with regard to these transfers. The baseline is the motive of Ricardian equivalence: if people have rational expectations and intend to leave positive bequest, with perfect capital market and lump-sum taxes, their consumption should remain unchanged because these transfers would not change their intertemporal budget constraints (Barro, 1974).4 However, people may also save these transfers for precautionary reasons (Leland, 1968), either because government transfers are generally associated with the expectations of greater economic uncertainties or because saving is the norm for prudent household budgeting when one is generally uncertain about the future.5 On the other hand, people may spend the transfers because of liquidity or borrowing constraints 2 See http://www.mof.gov.sg/budget_2006/index.html. The three schemes that involved cash transfers were Growth Dividends, National Service Bonus, and Workfare Bonus. See http://www.progress.gov.sg for details on the schemes. For example, a family of four could receive up to S$3,780 in cash under the Progress Package. The median household income in year 2005 was S$3,830. In general, the transfers were given out on 1 May 2006. The average exchange rate during 2006 was S$1=US$0.63. 4 Buchanan (1976) and O’Driscoll (1977) trace the idea back to David Ricardo. 5 After all, a government is more likely to give transfers in anticipation of bad times, the optimistic rhetoric behind the transfers notwithstanding. 3 2 (Hubbard and Judd, 1986)6, non lump-sum taxes (Barsky, Mankiw and Zeldes, 1986)7, population turnover and the entry of new households8, the expectations that the government may not need to raise future taxes to finance the transfers 9, myopia or present-bias (Laibson, 1997)10, rule-of-thumb consumption behavior (Campbell and Mankiw, 1989, Mankiw, 2000)11 due to mental accounting (Shefrin and Thaler, 1988)12, near rationality (Akerlof and Yellen, 1985)13 or spending norms (Akerlof, 2007).14 3. Methodology and Results The survey first asked the respondents whether they spent the transfers. It then summarized and presented eight standard textbook theories of Ricardian equivalence and non-equivalence in plain English, and asked the respondents to With the transfers, the government is effectively borrowing on the household’s behalf. If household either cannot borrow on its own or can only borrow at a higher interest rate than the government, then the transfers relax the household’s budget constraint, making higher consumption feasible. 7 With taxes as a function of income, a combination of government transfers today and higher taxes in the future raises the household’s lifetime after-tax income if its future income is low, and vice versa, thereby reducing the variance of the household’s after tax incomes and precautionary saving, thus inducing higher consumption. 8 With population turnover and the entry of new households, some of the future tax burden will be borne by the new households who are not alive at the time of the transfers. Thus, the transfers increase the lifetime resources of the individuals who are currently living, thereby raising their consumption. 9 People may expect the government to cut future spending or to finance the transfers using past accumulated surpluses. However, this last reason may be quite unique to Singapore because most countries have accumulated debts from deficits, not surpluses. 10 Present bias is attributable to the saliency of current consumption and can lead to self-control problem. Even if the consumers fully anticipate the future increase in tax burden and are fully aware of their self-control problem, the consumers will still spend the transfers, because the cash transfers relax their pre-imposed liquidity constraint (aimed at self-control). Myopia may aggravate the problem. The myopic consumers may feel wealthier and consume more because they fail to foresee or understand the budgetary implications of government transfers. 11 Rule-of-thumb consumers simply spend their current income. 12 Under mental accounting, incomes from different sources are treated differently, with higher marginal propensity to consume out of cash or check receipts, and lower propensity to consume out of planned savings and wealth. 13 Starting from optimal consumption, the utility foregone from not re-optimizing in the face of small income or fiscal shocks is even smaller (only second-order in magnitude). Thus, even a small cognitive cost of re-optimization may prevent fully rational utility-maximizing consumers from re-optimizing. 14 These consumption norms may arise from what the consumers think they should or should not spend, say because of what they perceive to be prudent household financial practices. 6 3 choose the statements that best described how they felt about the transfers.15 Table 1 reports the brief statements that were actually presented to the respondents and the respective behavioral motives tested. The respondents could, and sometimes did, choose more than one statements. Finally, the survey elicited the respondents’ expectations on future government taxes and spending given the transfers. The survey was presented in hardcopy to people on the streets during late February to late March 2007, roughly one year after the Package was announced.16 All respondents were adult citizens who did receive some cash transfers. To investigate to what extent competing motives affected the propensity to spend the transfers, Table 2 regresses the respondents’ self-reported spending decision on their chosen explanations and reports the odds ratios estimated using maximum likelihood logistic regression. The dependent variable is a dummy variable which equals one for spender (who reported having spent the transfers or planning to do so soon), and zero otherwise. The independent variables are eight dummy variables, each indicating whether a particular explanation was chosen. Being liquidity constrained predicts spending behavior perfectly; 35 respondents chose liquidity constraint and they were all spenders. Thus, they are dropped from the regression. All of the estimates are statistically significant at the 10% level except the coefficient on the bequest motive, which is also the smallest in magnitude. Three motives reduce the probability of spending the transfers. They are (in descending order of statistical and economic significance): precautionary saving, Ricardian equivalence, and the bequest motive. The effects of precautionary saving and Ricardian equivalence are statistically significant at the 1% level and 5% level respectively. Four motives raise the probability of spending the transfers. They are See, for example, David Romer’s (2006) Advanced Macroeconomics for a standard textbook treatment. 16 The actual survey form is available upon request. 15 4 (in descending order of economic significance): present bias, rule of thumb, entry of new households, and non lump-sum taxes. The effects of present bias and rule of thumb are both statistically significant at the 1% level, whereas the effects of entry of new households and non lump-sum taxes are statistically significant at the 10% level and 5% level respectively. Overall, precautionary saving, present bias, and rule of thumb are the most economically and statistically significant motives in changing the propensity to spend the transfers. Table 3 regresses the respondents’ choices of explanations on their personal characteristics and reports the odds ratios estimated using maximum likelihood logistic regressions. Column (1) investigates how an individual’s personal characteristics affected his consumption decision, using as the dependent variable a dummy variable which equals one for spender, and zero otherwise. Columns (2) to (9) examine how personal attributes affected consumption decision through the appeal of different motives, where the dependent variable in a particular column is a dummy variable which equals one if a particular explanation is chosen, and zero otherwise. The personal characteristics include a number of ordinal variables (for age group, educational attainment, income group, dwelling type) and dummy variables (for female, married persons, Ricardian expectations – the expectations that taxes would be higher because of the transfers – and the clueless regarding the budgetary implications of transfers).17 The evidence in Column (1) suggests that older, more educated, higher income individuals dwelling in more expensive residence were less likely to spend the transfers. The age effect is only marginally statistically significant at the 10% level, whereas education, income and dwelling type are statistically significant at the 5% The clueless refers to those who chose “don’t know” when asked about their budgetary expectations (on future taxes and government spending). 17 5 level. Female and married persons were more likely to spend the transfers but the effects are not statistically significant at the conventional levels. Both budgetary expectations reduced the probability of spending the transfers but the effects are not statistically significant at the conventional levels. It turns out that personal attributes were correlated with the appeal of different motives. Older respondents were more likely to choose Ricardian equivalence and non lump-sum taxes (both effects are statistically significant at the 10% level), but they were less likely to choose rule of thumb (the effect is statistically significant at the 1% level). The stronger appeal of Ricardian equivalence and the weaker appeal of rule of thumb discouraged spending, whereas the stronger appeal of non lump-sum taxes encouraged spending.18 The net effect is that older respondents were less likely to spend the transfers, as noted above. There is little evidence that men and women differed significantly in their spending decisions or motivations except that women seemed marginally less likely to choose the entry of new households to explain their behavior and the effect is marginally statistically significant at the 10% level. Naturally, married persons were much more likely to choose the bequest motive as they were more likely to have children. They were also less likely to be liquidity constrained. Both effects are statistically significant at the 5% level. The more educated were much less likely to be liquidity constrained and the effect is statistically significant at the 1% level. Somewhat surprisingly, general educational attainment had no statistically significant effect on the popularity of Ricardian equivalence, rule of thumb, or present bias. Income level also had no statistically significant effect on the popularity of any of the explanations. 18 They thought that when the government finally increased the taxes to finance the transfers, their tax burden would be lower because they would be earning and spending less. 6 Nevertheless, the largest effect appeared to work through non lump-sum taxes: higher income individuals were less likely to think that their tax burden would be lower in the future – they did not think that they would be earning or spending less when taxes were raised to finance the transfers. Respondents in more expensive dwellings were presumably wealthier. They were more likely to choose present bias (which encouraged spending and the effect is only marginally statistically significant at the 10% level) and less likely to choose rule of thumb (which discouraged spending and the effect is highly statistically significant at the 1% level). The net effect is that they were less likely to spend the transfers. Respondents with the Ricardian expectations were naturally more likely to choose Ricardian equivalence and the effect is statistically significant at the 5% level. However, they were also more likely to choose present bias and the effect is statistically significant at the 10% level. The net effect is that they were not significantly more likely to save the transfers. In comparison, those who were completely clueless about the budgetary implications of the transfers were not inclined to choose any particular explanation. Finally, despite its overall popularity, the appeal of precautionary saving was not significantly related to any of the personal characteristics included, suggesting that it might have been a general motivation that transcended personal characteristics. 3. Future Research The relative appeal of different motives may be quite sensitive to the specific context and background of government policy. Investigating the robustness of results reported here to other episodes of government transfers or tax cuts is a natural next step on the research agenda. 7 References Akerlof, G.A., 2007, The missing motivation in macroeconomics, American Economic Review 97, 5-36. Akerlof, G.A. and J.L. Yellen, 1985, A near-rational model of the business cycle, with wage and price inertia, Quarterly Journal of Economics 100 (Supplement), 823-838. Barro, R.J., 1974, Are government bonds net wealth? Journal of Political Economy 82, 1095-1117. Barsky, R.B., N.G. Mankiw and S.F. Zeldes, 1986, Ricardian consumers with Keynesian Propensities, American Economic Review 76, 676–689. Bewley, T.F., 1998, Why not cut pay? European Economic Review 42, 459-490. Blinder, A., 1994, On sticky prices: academic theories meet the real world, in N.G. Mankiw, Ed., Monetary Policy (University of Chicago Press), 117-150. Buchanan, J.M., 1976, Barro on the Ricardian equivalence, Journal of Political Economy 84, 337–342. Campbell, J.Y. and N.G. Mankiw, 1989, Consumption, income and interest rates: reinterpreting the time series evidence, NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 185-216. Hubbard, G.R. and K.L. Judd, 1986, Liquidity constraints, fiscal policy and consumption, Brooking Papers of Economic Activity 1, 1-60. Laibson, D., 1997, Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting, Quarterly Journal of Economics 112, 443–47. Leland, H.E., 1968, Saving and uncertainty: the precautionary demand for saving, Quarterly Journal of Economics 82, 465-473. Mankiw, N.G., 2000, The savers-spenders theory of fiscal policy, American Economic Review 90, 120-125. O'Driscoll, G.P., 1977, The Ricardian nonequivalence theorem, Journal of Political Economy 85, 207-210. Romer, D., 2006, Advanced Macroeconomics (McGraw-Hill/Irwin). Shefrin, H.M and R.H. Thaler, 1988, The behavioral life-cycle hypothesis, Economic Inquiry 26, 609-643. Shiller, R., 1996, Why do people dislike inflation? in C. Romer and D. Romer, Eds., Reducing Inflation: Motivation and Strategy (National Bureau of Economic Research and University of Chicago Press). 8 Table 1: Behavioral Motives Tested and Brief Descriptions Presented to the Respondents Underlying Theory Ricardian Equivalence Bequest Motive Liquidity Constraints Entry of New Households Non Lump-sum Taxes Precautionary Savings Present-Bias Rule of Thumb Others Brief Description Presented to the Respondents I will probably have to pay more taxes in the future because of the Progress Package. So I saved it for the future. The future generations will probably have to pay more taxes because of the Progress Package. But not for me. But I am worried for my sons and daughters. So I saved it for them. I spent it because I have already spent all my money. If I could borrow some money, I would have borrowed it and spent it. The future generations will probably have to pay more taxes because of the Progress Package. But not for me. So I do not worry about it and I spent it. Other people may have to pay more taxes in the future because of the Progress Package. But not for me. My tax burden will be lower in the future because I will be earning less or spending less when that happens.19 I do not know what my taxes will be in the future. But with so much uncertainty, I saved it for the rainy days. I will probably have to pay more taxes in the future because of the Progress Package. But I do not worry about the future. I spent it while I could. I do not know what my taxes will be in the future. As a general rule, I just spend whatever I receive in cash or in check, like the Progress Package. But I try not to touch my savings. Others 19 In Singapore, two main tax burdens on the individuals are income tax (which depends on income) and the Goods and Services Tax (i.e., GST, which depends on expenditure). 9 Table 2: Logistic Regression of Spending Decision on Behavioral Motives Dummy for Ricardian Equivalence Dummy for Bequest Motive Dummy for Entry of New Households Dummy for Non Lump-sum Taxes Dummy for Precautionary Saving Dummy for Present Bias Dummy for Rule-of-Thumb N Dummy for Spender 0.44 [0.14]** 0.6 [0.25] 8.7 [9.81]* 5.89 [4.26]** 0.31 [0.09]*** 30.23 [32.68]*** 14.39 [6.80]*** 460 Notes: The dummy for liquidity constraint and the 35 respondents who chose liquidity constraint are dropped because they predict spending behavior perfectly. This table reports the odds ratios. Robust standard errors are in the brackets. * Significant at 10%; ** Significant at 5%; *** Significant at 1%. Table 3: Logistic Regression of Spending Decision and Motivations on Individual Characteristics Dependent Variable = Dummy for Spending Decision and Motivations [1] Spender Age Group Female Dummy Educational Attainment Income Group Married Dummy Residential Type Ricardian Exp. Dummy Clueless Exp. Dummy N 0.89 [0.06]* 1.27 [0.29] 0.83 [0.07]** 0.86 [0.06]** 1.04 [0.27] 0.86 [0.06]** 0.69 [0.22] 0.62 [0.23] 469 [2] Ricardian Equivalence 1.15 [0.09]* 0.69 [0.18] 1.11 [0.11] 1.02 [0.09] 0.62 [0.20] 1.01 [0.08] 2.59 [1.00]** 1.46 [0.69] 469 [3] Bequest Motive 1.18 [0.13] 0.54 [0.21] 1.03 [0.15] 1.05 [0.12] 3.55 [1.81]** 0.85 [0.11] 2.72 [1.69] 1.41 [1.09] 469 [4] Liquidity Constraint 0.96 [0.12] 0.92 [0.36] 0.66 [0.10]*** 0.91 [0.11] 0.3 [0.17]** 0.86 [0.12] 0.63 [0.29] 0.64 [0.36] 469 [5] Entry of New Households 1.14 [0.10] 0.57 [0.18]* 1 [0.12] 0.96 [0.10] 1.22 [0.41] 0.84 [0.10] 0.85 [0.33] 0.64 [0.32] 469 [6] Non Lumpsum Taxes 1.23 [0.13]* 1.32 [0.48] 0.9 [0.13] 0.81 [0.11] 0.68 [0.33] 0.89 [0.11] 0.63 [0.27] 0.62 [0.35] 469 Notes: 1. This table reports the odds ratios. 2. Robust standard errors are in the brackets. * Significant at 10%; ** Significant at 5%; *** Significant at 1%. [7] Precautionary Saving 0.99 [0.06] 1.26 [0.26] 1.11 [0.08] 0.99 [0.06] 1.02 [0.26] 1.04 [0.07] 0.99 [0.27] 0.96 [0.32] 469 [8] Present Bias 1.03 [0.08] 1.02 [0.24] 1.07 [0.11] 0.96 [0.08] 0.62 [0.20] 1.12 [0.08]* 1.92 [0.68]* 1.17 [0.52] 469 [9] Rule-ofThumb 0.81 [0.06]*** 1.04 [0.21] 1.04 [0.08] 0.99 [0.07] 1.5 [0.38] 0.83 [0.06]*** 1.09 [0.30] 1.6 [0.53] 469