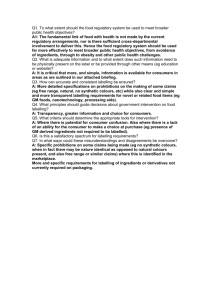

Part 2: FOOD LABELLING - OVERVIEW

advertisement