Casual Work and Casualisation – How Does Australia

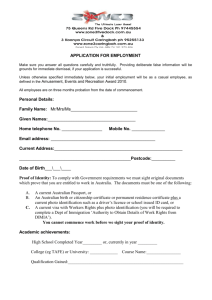

advertisement