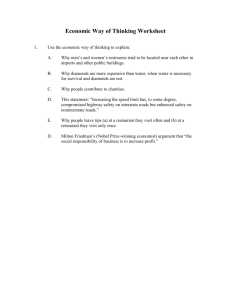

Rutgers Model United Nations

advertisement

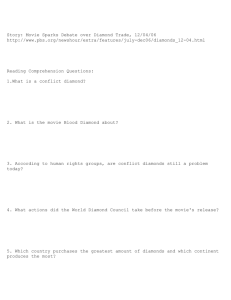

Dave De Camp and Dean Miller Rutgers Model United Nations 16 – 19 November 2006 United Arab Emirates Social, Humanitarian & Cultural Committee (SocHum) Topic: Civil Rights and Diamond Trading in Western Africa Notre Dame High School BACKGROUND Conflict diamonds are “diamonds that originate from areas controlled by forces or factions opposed to legitimate and internationally recognized governments, and are used to fund military action in opposition to those governments, or in contravention of the decisions of the Security Council” (Campino). In many rebel movements, conflict diamonds are their primary source of funding. This type of corruption is especially commonplace in countries in Western Africa where diamond mines are prevalent. Although most diamonds mined are legitimate, conflict diamonds account for up to fifteen percent of the market share (Korostoff 3 of 27). These conflict diamonds are easily smuggled into the international market due to their accessibility and low transportation costs. The high demand and steady price in the worldwide market make transporting diamonds a minimal financial threat. By the time a conflict diamond reaches the international market its origins are virtually unknown due to the number of merchants a diamond may pass through. The only solution to determining a diamond’s point of origin by the time it reaches the international market is to have a chemical analysis performed, a practice that is very impractical (4 of 27). Since the late 1800’s the De Beers Group has held a near complete monopoly over the diamond market worldwide. Over time the De Beers group eventually gained control of 1 more than ninety percent of the diamond industry. The De Beers group, due to its monopoly, was able to allow only enough diamonds into the international market as required by demand, and store the remaining supply in a London vault (6 of 27). In this way the De Beers group was able to keep the prices of diamonds artificially high. In order to maintain their monopoly and control of the diamond market, they tried to buy all the rough diamonds available, including conflict diamonds (6 of 7). By the year 2000, the De Beers’ market control dropped to sixty-five percent of the diamond industry. Knowing that it would be virtually impossible for them to regain their earlier role as sole market custodian, the De Beers Group voluntarily agreed to reform their business practices (7 of 27). They decided they would no longer set the prices of diamonds, but would rather let the market itself set fair prices for diamonds; moreover, they also decided to stop trying to buy all the rough diamonds available on the market, only purchasing from their own diamond mines (7 of 27). The De Beers Group entered the retail market as well, selling cut diamonds for the first time. The De Beers Group, most importantly, also chose to gradually empty their stockpile. When the stockpile is totally depleted, the company will finally be able to know the source of every single diamond that passes through their control (8 of 27). The De Beers group’s reform will aid in the elimination of conflict diamonds in the worldwide market. Due to capital gained from conflict diamonds, rebel factions have been able to finance their operations. In Angola, a political group known as the National Union for Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) fought for power with the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) for control of the government from 1975 to 2002 (9 of 27). UNITA used conflict diamonds as a source of revenue, thus continuing a brutal civil war until MPLA forces killed the UNITA leader, Jonas Savimbi (9 of 27). During the course of a brutal civil war, Uganda and Rwanda invaded the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1998 in order to gain control of prosperous diamond fields (10 of 27). Sierra Leone has been in 2 continuous conflict since 1991 because of actions of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). In 1991 the RUF attempted to seize Leonese diamond mines. For the following ten years the RUF committed numerous atrocities, such as mastication, rape and even cannibalism, in attempt to control these diamond mines (11 of 27). In 1999, the UN attempted to respond to the RUF through the Lomè Peace Accords, but was largely ineffective because the RUF retained control of the nation’s diamond mines. Fighting resumed shortly and continued until a ceasefire was agreed to in 2001. By 2002, the RUF ceased to exist (13 of 27). Without the revenue from conflict diamonds, these rebel organizations would not have been able to generate substantial funds to finance their operations, and thousands of live could have been spared. On December 1, 2000, the United Nations adopted the Kimberly Process Certification Scheme, which has been the most effective resolution to eliminating the distribution of conflict diamonds. The KPCS “aims to create a certification system for rough diamonds which will exclude conflict diamonds from the legitimate trade” (Smillie 1 of 24). The Kimberley Process is endorsed by the United Nations but independently operated and managed. Membership in the KPCS is completely voluntary. There are currently 69 participating nations in the KPCS, which account for 99.8 percent of the world diamond production (Korostoff 15 of 27). Participants in the KPCS must agree to transport diamonds in tamper proof containers with a certificate that contains the nation of origin, nation of last export, and the weight and value of the diamonds, and “establish a system of internal controls designed to eliminate the presence of conflict diamonds from the shipments of rough diamonds imported into and exported from its territory” (16 of 27). Furthermore, participants must agree not to trade diamonds with any nation that is not involved in the KPCS. One of the few flaws in the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme is that the only punishment for violation of the KPCS’s conditions is expulsion from the scheme (20 of 27). Another 3 shortcoming of the KPCS is that it only deals with diamonds at the beginning of the export stage (19 of 20). Illegally mined diamonds, by the time they reach the export stage, could have already passed through so many hands that the original source is untraceable. Thus the UN is faced with a troublesome dilemma: Should they continue to promote the current KPCS, which remains the most effective measure against the distribution of conflict diamonds, attempt to modify the KPCS to make the scheme more effective, or abandon the KPCS entirely and formulate another course of action? POSITION The United Arab Emirates is an active participant in the Kimberly Process Certification Scheme. We are one of the few Middle Eastern countries that back the KPCS. The UAE is an ardent supporter of the KPCS and urges other nations to join. The UAE sees conflict diamonds as both a threat to their people, by financing various terrorist groups, and to the diamond industry as a whole. The United Arab Emirates wishes to promote the Kimberly Process Certification Scheme so that enough countries join to eliminate conflict diamonds. Once conflict diamonds are eliminated from the market, the industry of legitimate diamonds can flourish. The United Nations as a whole endorses the KPCS as a solution to conflict diamonds and will continue to back the KPCS because it has been the most successful resolution to conflict diamonds. The United Nations might urge the KPCS to impose stricter penalties for violating countries such as boycotts on violator’s diamonds, but cannot force the KPCS to do so because they are independent of one another. The UN might encounter opposition from those countries in which legitimate diamonds are produced. These countries feel that their legitimate diamonds might be confused as conflict diamonds, thus hurting their industry. Other countries feel that the KPCS does not work all together and have, therefore, implanted their own certification schemes. 4 Works Cited Campino, Anna Frangipani. “Conflict Diamonds: Sanctions and War.” United Nations Department of Public Information. 21 March 2001. 29 October 2006 <http://www.un.org/peace/africa/Diamond.html>. Korostoff, Matt. “Civil Rights and Diamond Trading in Western Africa” Rutgers Model United Nations Director’s Brief for the Social, Humanitarian and Cultural Committee. The Institute for Domestic and International Affairs. 2006. 29 October 2006 <http://www.idia.net/Files/ConferenceCommitteeTopicFiles/34/PDFFile/U06SocHu m-CivilRightsandConflictDiamonds.pdf>. Smillie, Ian. “The Kimberly Process: The Case for Proper Monitoring.” Partnership Africa Canada, September 2002. 29 October 2006 <http://action.web.ca/home/pac/attach/KP%20Monitoring.pdf#search=%22Kimberle y%20Process%22>. 5