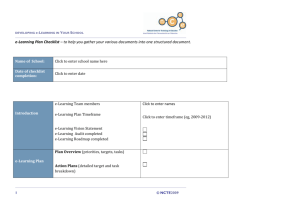

work based e-learning review

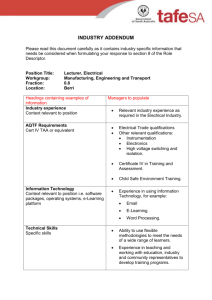

advertisement