China Mist Tea Company Launch - Optimal Enterprise. Achieve More.

advertisement

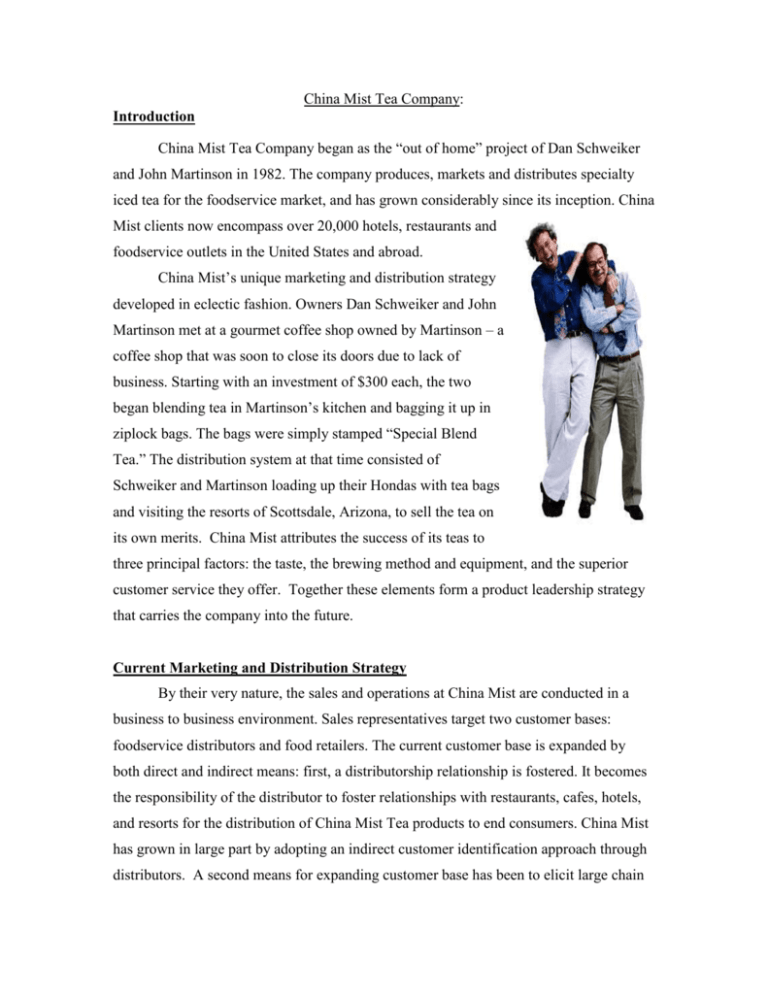

China Mist Tea Company: Introduction China Mist Tea Company began as the “out of home” project of Dan Schweiker and John Martinson in 1982. The company produces, markets and distributes specialty iced tea for the foodservice market, and has grown considerably since its inception. China Mist clients now encompass over 20,000 hotels, restaurants and foodservice outlets in the United States and abroad. China Mist’s unique marketing and distribution strategy developed in eclectic fashion. Owners Dan Schweiker and John Martinson met at a gourmet coffee shop owned by Martinson – a coffee shop that was soon to close its doors due to lack of business. Starting with an investment of $300 each, the two began blending tea in Martinson’s kitchen and bagging it up in ziplock bags. The bags were simply stamped “Special Blend Tea.” The distribution system at that time consisted of Schweiker and Martinson loading up their Hondas with tea bags and visiting the resorts of Scottsdale, Arizona, to sell the tea on its own merits. China Mist attributes the success of its teas to three principal factors: the taste, the brewing method and equipment, and the superior customer service they offer. Together these elements form a product leadership strategy that carries the company into the future. Current Marketing and Distribution Strategy By their very nature, the sales and operations at China Mist are conducted in a business to business environment. Sales representatives target two customer bases: foodservice distributors and food retailers. The current customer base is expanded by both direct and indirect means: first, a distributorship relationship is fostered. It becomes the responsibility of the distributor to foster relationships with restaurants, cafes, hotels, and resorts for the distribution of China Mist Tea products to end consumers. China Mist has grown in large part by adopting an indirect customer identification approach through distributors. A second means for expanding customer base has been to elicit large chain businesses—designated key accounts—which are recruited directly by the sales representatives. Under this scenario, convenient distributors are then selected to source and service these contracts. These relationships are managed more in accordance with the company’s strategy of product leadership than with relationship marketing. In fact, their success has been predicated upon a workable model that distinguishes them in the beverage industry. China Mist employs three regional sales people in Los Angeles, Atlanta and Portland. These salespeople essentially divide the country in thirds: the Atlanta representative covers all territory between the Mississippi and the East Coast; the Los Angeles representative covers accounts on the West Coast; the Portland representative takes everything in between. Incidentally, this distribution is equitable because the West Coast—with its warm climate—represents the majority of China Mist sales. In fact, 25% of the company’s sales come from the state of California. China Mist is one of the only fresh-brewed ice tea retailers in the United States. The company offers a product mix consisting of two central product lines: Black Teas (private blend and flavored) and Green Teas (straight and naturally flavored). While the “house” blend is currently the most popular, the entire product line is offered to individual retailers. Given the competition that fresh-brewed iced tea faces among soft drinks and other beverages in a restaurant, China Mist avoided cannibalization of its own sales by encouraging retailers to sell one flavor of tea. With the recent introduction of Green Teas, the company has been able to achieve a more ideal marketing mix—offering both lines as complementary products to retailers. The question of which flavor most appeals to end consumers varies by region, and is an issue to be faced in light of international expansion. In the future, this product variety may come to be a source of competitive advantage for the company. One of the major selling points of China Mist Tea, and a central component of its marketing strategy, is its Tea Loving Care program (TLC). This Tea Loving Care preventative maintenance program is implemented by the distributor. Essentially, the distributor does a monthly cleaning of the brewing equipment, ensuring not only that the taste of the tea will remain fresh and pure, but that the machine is free of dangerous 2 microbes that could contaminate the product. This program is a central selling point. As a sales tactic, China Mist distributors or salespeople often ask restaurant managers to remove the spigot of their current tea equipment. There is very often a significant mass of sticky bacterial residue that has built up over time. Recently, there was a scare among retailers and end consumers in the U.S. when a national news program ran a story on the bacteria present in restaurant iced tea dispensers. China Mist was able to use this incident as part of their product differentiation strategy to set their company apart from the competition by emphasizing the regular maintenance program. Another essential element in the company’s strategy revolves around the use of brewing equipment. Appropriate equipment plays a crucial role in China Mist’s marketing and distribution strategy. The company insists that distributors mandate the use of what is termed a “dedicated iced tea brewer,” which distinguishes it from a water processor used to brew coffee as well. This insistence ensures the pure taste of the brewed tea. While China Mist is not always able to monitor this situation, the company does increase the likelihood of compliance by providing free equipment to the customer. In effect, China Mist owns the brewing equipment and has the right to dictate that it is used only for the brewing of their product. Restaurateurs seem motivated by this policy as well, given the high per glass profits of brewed iced tea in relation to other beverages. The brewing equipment is not actually paid for by China Mist, but by the distributor. In return, the distributors receive the right to distribute the China Mist line of products. To ensure quality consistency, China Mist requires the distributor to purchase the brewers from a list of manufacturers, with prices ranging from $350 per unit to $500 per unit. International distributors recently explained to China Mist that they had restaurants willing to purchase the equipment themselves, relieving the distributor from the obligation. China Mist insisted that the distributor purchase the equipment as required in their contract. According to the company, if the restaurant owns the equipment, they can use it at their discretion brewing coffees, even shifting to another tea product, if the distributor switches to another brand. The “dedicated brew machine,” therefore, becomes a sunk cost for distributors and both a differentiating factor and a barrier to entry held by China Mist against competitors. 3 Pricing is extremely important in the iced tea business to maximize sales volume. Volume is particularly important because of the price considerations in this industry, which are often decided on a per glass basis. Under this framework, brewed ice tea has show to be extremely profitable. The average cost per glass is 2-5 cents versus 8-10 cents for soda products that retail at the same price). As a result, not only can distributors benefit from significant profits, earning profit margins of over 100%, but the restaurants, hotels and resorts that sell the product also earn sizable per glass profits. Thus, it is in the foodservice organization’s interest to promote the sale of the iced tea over the lower margin soft drinks. On certain occasions, hotel or restaurant chains that are designated key accounts receive a portion of the earnings as well, in the form of a rebate. These large hotel or restaurant chains comprise a large portion of the China Mist customer base. One of these customers is Starwood Lodging, which has grown through acquisitions to become one of the largest hotel chains in the world. Starwood receives a rebate based on each case of tea purchased. This rebate cost is shared between China Mist and the distributor, with China Mist covering 70% of the rebate and the distributor covering the remaining 30%. This relationship not only benefits China Mist, but also the distributor. Not only do key accounts represent high volume, but the acquisition costs of the account are shouldered by China Mist. China Mist charges the same price to its distributors across the board – both domestic and internationally—in order not to compete on price in different markets. Concessions once given are hard to regain. Despite the differences in currency, the resulting tea price fluctuation on a per glass basis is minimal at two to three cents difference per glass. China Mist has, on occasion, made an exception to this practice, as is the current case with a Korean distributor benefiting from a 10% discount. This exception was made because of the extremely high import tax placed on tea entering the country. This tax rendered the product prohibitively expensive compared to competing beverages in the market. China Mist has only recently begun a push to expand international sales. Two years ago, the company dedicated a full-time position to expanding its international marketing efforts. Currently, only 8% of the company’s revenues are attributed to non- 4 domestic markets. Internationally, China Mist distributes its product in the Cayman Islands, Jamaica, Canada, Mexico, Guam, Saipan, Hawaii, Korea, Singapore, Japan, Aruba, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala and Puerto Rico. One of the countries China Mist is currently exploring as a possible market is the Philippines. This country has been identified due to its warm climate, affinity for American culture, and a growing tourism industry. Political Economy with the Philippines As China Mist contemplates expanding the scope of its distributor and retail relationships to include the Philippines, it must consider how best to evaluate its current operations in lights of the salient economic, governmental, and social factors of trade in this environment. Prior to pursuing international expansion in any country, it only makes sense to size up the economic situation. There is no reason to downplay the deleterious effects of the “Asian Financial Crisis” on the Philippine economy. After a period of accelerated growth from 1992-1996, real growth of the Gross National Product (GNP) slowed to 5% and down to 2.5% in 1998 (Dept. of Commerce, 1998). A reciprocal hike in inflation accompanied this downturn, growing from single digits as low as 5% from 1992-1997 and reaching 10% in 1998. With this slowdown in the economy, the foreign debt has increased nominally to US$45.4 billion at the end of 1997. This represents a debt to GNP ratio of 53%. While still substantially leveraged, it must be noted that this ratio has, despite the crisis, improved by 65% from 1990, and even more from its historical high of 96% in 1986. The country’s currency, the peso, has depreciated 35% against the US dollar since mid-1997. Such a combination of rising inflation, a weaker currency, high financing costs, and the ruinous effects of El Niño have been incorporated into elevated price levels. Such generic indices, however, do not capture the potential of what economist have agreed is a generally positive potential for long-term growth. The Philippine market hosts a wide array of American companies in many fields, including food and beverage manufacturing, consumer products, agriculture and 5 healthcare. Many U.S. firms have been in the country since the early 1900’s. American companies have prospered over the long term and view the Philippines as a country where they can do business profitably and comfortably. The western orientation, English language, heritage, democratic government and inter-linked history going back to 1898, all play a role in the attractiveness of this country to American companies. The relevant ties form the basis for the U.S. position as both the country’s largest direct equity investor and its largest trading partner. Since the restoration of a democratically elected government in 1986, the Philippines’ democracy has continued on a path of stronger and healthier institutions, more openness and more transparency. President Estrada is committed not only to forging a democratic government, but also to opening industries and markets. He has worked with the other two branches of government in the recent establishment for the Philippines of a domestically stable, secure environment for economic and commercial activity. Corruption nonetheless remains a potential concern, as laws are often times ineffective or difficult to enforce. In comparing the Philippines to eleven other Asian countries in areas such as country risk issues and trade and investment, the rankings for the Philippines demonstrate only mild risks. They are summarized in the following table: (Scale of 1-12) Country Risk Issues Philippine Rank Level of corruption 4 Social unrest 6 Political Leadership 4 Business Transparency 4 Trade and Investment Freedom to import products 6 Level of IPR protection 4 Freedom for MNCs to invest 6 Openness to serve local markets 4 In comparing these aggregate figures to those of other developing countries in the region, the Philippines represents a relatively comfortable environment in which China Mist can do business. 6 Philippine Import Policies The current structure of operations at China Mist coincides well with the recent focus in the Philippines on increasing foreign partnerships with local businesses. Not only are import distributors numerous (especially around Manila and several “free trade” zones), but distributorships and dealership arrangements are considered purely private contracts by the government and are not tightly regulated. Theoretically, a producer may sell the same goods to different dealers at varying prices. However, China Mist has made it a policy to develop open and loyal relationships with its distributors, in which case such practices could prove tricky. Moreover, producers normally offer graduated discounts equally to its dealers or buyers, and the terms are known to all. Thanks to recent property right legislation, unauthorized dealers that sell foreign-sourced merchandise may be sued, especially if the goods carry well-known trademarks. No laws exist in resale-price maintenance, although some products are periodically subject to price controls by the government. As a result, some producers suggest retail prices for their products. This is common practice for soft drinks, beer, candy and cigarettes, but has not been a concern for loose tea. While it should be noted that price variations rarely go beyond 5-10% of suggested retail prices, in some instances, for example “up-market” establishments such as five star hotels, restaurants and resorts, retailers are known to charge up to twice the retail level. This colloquial pricing system must be accounted for in China Mist’s decisions regarding distribution sources and direct retail contracts in the Philippines. While tariffs vary depending on the imported item, the Philippines’ average tariff rates continue to come down as the country approaches its 2004 goal of a uniform tariff rate of 5%. Tariffs on tea (flavored and unflavored) fall under tariff heading 0902 and are presented in the following table: HS Number Description 1997 1998 1999 2000 0902.10 00 Green tea (not fermented) in immediate packings 20.00 10.00 10.00 10.00 0902.20 00 Other green tea (not fermented) 20.00 10.00 10.00 10.00 0902.30 00 Black tea (fermented) and partly fermented tea, in 20.00 10.00 10.00 10.00 20.00 10.00 10.00 10.00 immediate packings of a content no more than 3kg 0902.40 00 Other black tea (fermented) and other partly fermented tea 7 Imports of items in 1,720 categories (out of 1902) have been liberalized so far, and it is likely that tea will join this category in the course of the next two years. Whether subject to duties or not, all imported articles must pass through customs at the port of entry. The following documents are generally required: Declaration of import entry; Commercial or pro forma invoice; Certificate of origin; Bill of lading; Irrevocable letters of credit, bank guarantee or warehousing bond; Inward cargo manifest; Pertinent documents and permits required by the Bureau of Customs or other government agencies. Letters of credit are required for all imports valued at greater than $500 (and for lower-valued shipments under certain conditions). Exceptions are allowed in documentsagainst-acceptance and open-account arrangements, consignments, and no-dollar and lease/purchase arrangements. Payment terms under documents-against-acceptance and open-account arrangements generally may not exceed 360 days. Longer terms require approval from the Bangko Sentral Pilipinas (BSP). Payments for imports of various other commodities (for example, wheat, raw cotton and leaf tobacco) are allowed only if financed under special official credit arrangements. Requirements for labeling and marking imported goods state that product labels must provide the following information: Country of origin; Brand; Trademark or trade name; Physical or chemical composition; Net weight and measure (if applicable); Address of the manufacturer or re-packer. Within the Philippines, the penalties for misrepresentation or improper labeling (meant to discourage smuggling) range up to P5000 in fines and six months in prison. If a legitimate shipment does not bear a proper mark of origin, it is subject to a 5% penalty tax. The government has globalized its comprehensive import surveillance scheme (CISS), which is designed to monitor imports for quality, quantity, price and conformity with the Tariff and Customs Code. At present, the Swiss firm Societe Generale de Surveillance (SGS) inspects all import shipments valued at $500 or more. An SGS report (the Clean Report on Findings) is required for Philippine customs clearance. The contract for the CISS was renewed in March 1998; it will remain in effect until end-1999. The elements raised in this section demonstrate that the business environment of the Philippines represents a solid one for China Mist to engage in the expansion of their international markets. 8 Market Potential The Philippine islands have an aggregate population of over 72 million people (1997), which continues to grow at a rate of 2.3% per annum. While Filipino is the national language and is the most common means of communication, English is commonly used in the government and business arenas. Especially at the level of management, almost all Filipinos have good to excellent English skills and are able to conduct business in this language. Such skills should facilitate the development and maintenance of relationships between China Mist and local distributorships, and may serve as a framework for future efforts at relationship management by the company. China Mist has the opportunity to engage two of the top three sectors expected to lead in exports from the US to the Philippines: Food Processing and Packaging; and Hotels and Restaurants. Throughout 1997 and 1998, the Philippine beverage industry continued to grow through intense local competition. Sales volume grew in beer, soft drinks, wine and spirits, fruit juices and drinks, and in ice cream. The three largest national food and beverage companies all showed marked improvement. Republic Flour Mills registered an increase of net income from US$12 million to US$15 million. Cosmos Bottling Company, a sister company, showed increases from US$7.7 million to US$12.7 million in sales. The San Miguel Corporation witnessed reduced profits but increased domestic market growth in beer (9%), food and agribusiness (22%), and packaging (14%). The competition to these national producers comes from the US, Italy, Germany, and Japan. Initial research indicates that none of these competitors is focused on the fresh-brewed ice tea segment within the beverage industry. While the overall increases in these markets indicates the potential for growth in the fresh-brewed iced tea market, it is necessary to focus specifically on the areas in which China Mist typically gains the majority of its sales: Hotels, Resorts and Restaurants. These are all venues whose growth corresponds with the growth of tourism. Taking a snapshot of the tourism industry in the Philippines shows that the estimate of tourism-oriented activities such as hotels, transportation, and accommodations has grown continuously since 1997, when Philippine tourism totaled US$518 million. To continue this expansion and to help the Philippines catch up with other Asian countries, The 9 Philippine Department of Tourism (DOT) is currently implementing a new strategy that aims to make tourism a major economic sector. Present statistics show that the average number of tourists arriving in the Philippines is 2.2 million people per year (Asia Pulse Magazine, 1998). The DOT expects the number of tourists to increase to 3 million by the year 2003, resulting in anticipated earnings of US $4.5 billion. In order to facilitate this increase in tourism the DOT has structured a “Rediscovery” program consisting of six major strategies, some of which will directly benefit China Mist. First, the DOT will utilize a combination of niche and mass market strategies to develop both special interest tourism and vacation resort destinations. Their goal is to expand tourism among both domestic and foreign markets, especially among tourists coming from the U.S. Fortunately for China Mist, the global leader in iced tea consumption continues to be Americans. Second, the DOT will implement a cluster development approach, based on the gateway and satellite destination concept, to develop destinations in Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. This will undoubtedly increase access to distribution channels for China Mist as well as increase the number of resorts in the Philippines. Third, the Philippine government is in the process of improving national support systems, such as transport services and ground infrastructure. Again, this clearly will benefit the distribution of China Mist to those resort and vacation destinations outside of the major urban hubs. Examples of these tourism destinations include the Luzon Cluster, positioned as a multifaceted destination with a full range of markets and products; the Visayas, as a resort center because of the high quality of beaches and tropical beauty; and Mindanao Cluster, as an exotic wilderness and colorful cultural destination. Each cluster is being developed to contain one or more primary gateways of world class international airports, a number of secondary gateways or domestic airports and a variety of existing, emerging and potential destinations. According to the Philippine Department of Tourism, in 1998 there were a total of 198 hotels in the country of which 21 were deluxe, 11 first class, 91 standard, 66 economy, and 9 unclassified. In 1998, Manila boasted a total of 13,101 available hotel rooms, compared with 12,264 rooms in 1997. Overall there was a 6.82% increase in room supply among classified hotels in metro Manila from 1997-1998. This increase in 10 rooms was distributed as follows: deluxe, 15.60%; first class, 19.65%; standard, 20.94% and economy, 7.81% (Businessworld, Philippines, 1998). There are currently 16 deluxe hotels operating in the Manila area alone. This trend is excellent news for China Mist in terms of an increased direct target market for key accounts. One of the hotels undergoing significant expansion is the deluxe Westin Philippine Plaza. The Westin hotel chain is owned by Starwood Hotels and Resorts Worldwide, Inc., an existing U.S. client of China Mist Tea. China Mist may be able to leverage this domestic relationship to provide additional opportunities in the Philippine market. Understandably, U.S. Starwood executives would not mandate which brand of iced tea a particular Philippine hotel must carry. However, by properly managing the business to business relationship with Starwood, there is a significant likelihood that China Mist’s existing relationship can be parlayed into a sales opportunity with Westin Philippine Plaza. Likewise, there are other existing U.S. China Mist customers with locations in the Philippines, with whom the company can attempt to expand the existing relationship. As a subset of the hotel industry, resorts represent a large percentage of current China Mist revenues. The number of resorts is currently limited in the Philippines. However, this is a market that has been targeted for growth by the Philippine Department of Tourism. Given the focus on resort development and expected increases in tourism China Mist should look to grow with this industry. China Mist has the opportunity to build brand awareness through other channels while keeping a close eye on the growing resort industry and developing relationships with resort developers as the opportunities present themselves. In a related sector, the restaurant industry continues to expand quickly. Its success is attributed to “steady population growth, changing consumer preferences, greater diversity in food, and increasing urban middle class, and an increase in the number of shopping malls” (US Dept. of Commerce, 1999). This last growth category has heralded the arrival to the Philippines of myriad American fast food franchises (currently over 60), including Bennigan’s, Outback Steakhouse, Starbucks Café, American Bistro, Planet Hollywood, Chili’s Bar & Grill, Pizza Hut, California Pizza Kitchen, Magoo’s, Greenwich, TGI Friday’s, Angelino’s, Domino’s Sbarro, Numero 11 Uno, and Little Caesar’s. These new entrants complement the strong presence of McDonald’s (181stores), Kentucky Fried Chicken (80 stores) and Dunkin Donuts (300 stores). Not only have these US chains entered the Philippine market, but they have also spread from Manila to vital regional cities such as Cebu, Davao, and Cagayan de Oro. These restaurants can also serve as a basis for integrating key accounts domestically and internationally. As of March 1999, the total dining out expenditure for the Philippine market was estimated at 38 billion pesos. Of the 38 billion pesos, 68% will go to the fast food market with the remaining 32% headed for the full service restaurants (SG Securities Research, March 1999). The fact that western-style casual dining restaurants continue to do well in the Philippines provides a wealth of opportunity for China Mist to utilize distributors and chain accounts to reach both local consumers and American tourists in the Philippines. Conclusion and Recommendations Inherently, the China Mist business model does not encompass direct end-user sales. As a result, their contact with distributors and large retail chains fall under the auspices of a business to business management structure. Although the company has existing relations with distributors in Southeast Asia, it should consider the advantages that would stem from using domestic distributors in the Philippines. Not only are domestic distributors consistent with the successful model that China Mist has adopted in the U.S, but they are also important strategically. Domestic distributors are more motivated to garnish customers and grow sales within their home market, and as such are China Mist’s primary means of expanding its sales base internationally. The selection of distributors must not only take into account political and regulatory factors, but must also emphasize those distributors currently well-poised within the hotel, resort, and franchise restaurant sectors. Political and economic factors also affect the company’s business to business management decisions. State monopolies, political strife, and economic instability may add to the difficulties in conducting business in the Philippines. Currently, however, these elements appear to support China Mist’s activities. Given that the company plans to continue using independent distributors and direct chain accounts to sell its product, 12 instead of directly investing in the market, fewer restrictions or governmental polices will apply. As previously noted, distributorship arrangements are considered purely private contracts and are not closely regulated. This type of arrangement greatly differs from direct foreign investment arrangements, which are much more regulated. While tariffs remain quite high (in comparison to many other food stuffs), government efforts to reduce tariffs to a flat rate of 5% are underway. With the combined influx of foreign direct investment and effort from the Department of Tourism to increase resort development and the image of the Philippine Islands as a tourist destination, the future looks bright. Both of these factors mean greater numbers of Americans in the tropical climate of the Philippines. These potential customers will be looking for cool and refreshing beverages. Commencing operations in a new country always poses a number of special problems and circumstances that need to be addressed. Two issues need to be studied in detail going forward: one, the management of relationships with decision makers and gatekeepers both within Philippine distributors and the corporate offices of key accounts. Specifically, China Mist must understand the cultural nuances of doing business in the Philippines. A second concern is the maintenance of product quality. Convincing China Mist distributors in the Philippines to adopt the Tea Loving Care program according to the American model poses a potential challenge. Furthermore, under the current business model the distributor purchases the brewing equipment. In a country that is considered a developing economy, this may greatly reduce the number of distributors who are both willing and able to work with China Mist due to the initial capital expense for provision of the brewing equipment. We believe these to be the two largest hurdles facing China Mist in the immediate future if the company pursues a policy of implementing the existing American model for operations in the Philippines. After considering the pros and cons of initiating business in the Philippines we feel the company should go forward with expansion plans. We propose the following recommendations: First, we feel there may be some definite advantages from establishing and nurturing a few key domestic distribution relationships in the area around Manila versus using large multinational distributors servicing all of Southeast Asia. This would allow China Mist to grow in lockstep with those distributors that should directly benefit 13 from the increased direct foreign investment, hotel and tourism industries. Assuming demand continues to increase for the reasons cited above China Mist will have the relationships and infrastructure in place to maximize every opportunity. Second, as soon as the level of business conducted by China Mist in South East Asia justifies, an account/quality management person would need to be placed in the region. Having an intermediary (even through a central distributor) in place acting as a liaison between accounts and distributors as well as following up on quality control issues—i.e the TLC program—will go a very long way in helping China Mist develop business in the region. Given the affinity for American products, a final consideration revolves around developing brand equity in this region using the “China Mist” label. We believe a market study is necessary to determine the relationship between demand and the potential misperception by domestic and international end consumers that they are purchasing a Chinese product rather than an American product. In other words, as China Mist expands into the Philippines, they need to develop a global brand management strategy that will be successful across borders. While intermediaries within the distribution channel recognize China Mist, can the company successfully convey brand equity to end consumers? This issue must be addressed as the company considers an immediate course of action. The Philippines hold great potential for China Mist. Both in terms of its market and the potential for developing solid multi-channel distribution, the Philippines represents a fruitful area for expansion. Nonetheless, to capitalize upon these opportunities, China Mist must carefully and successfully translate a business developed in the United States for this new market. The foundation for such a translation continues to be a solid product supported by communication, commitment, and trust with future business to business relationships. 14 Bibliography Electronic Sources: 1. Http://www.doh.gov.ph 2. Http:/www.dot.com.ph/amcham/index.html 3. Http://www.doc.gov 4. Http://www.ustr.gov 5. Http://www.infoserv2.ita.doc.gov/apweb.nsf 6. Http://www.ita.gov 7. Economic Intelligence Unit Database (Thunderbird IBIC) 8. Philippine Department of Tourism Paper Sources: 1. Asia Pulse, March 1999 2. Businessworld Philippines, 1998 3. SG Securities Research, March 1999 4. U.S. Department of Commerce, 1998 5. The Philippine Star, July1996 6. The Economist, May 1996 7. Asia Money, March 1996 15