Creating A Space for “Every woman” at Oprah

advertisement

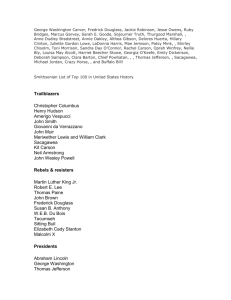

RUNNING HEAD: Creating a Space CREATING A SPACE FOR “EVERY WOMAN” AT OPRAH.COM Leda Cooks, Associate Professor Erica Scharrer, Assistant Professor Mari Paredes, Assistant Professor Department of Communication University of MA, Amherst Amherst, MA 01003 Fax 413 545 6399 Contact phone 413 545 2895 Email leda@comm.umass.edu Paper submitted for consideration to the Communication and Technology Division of the International Communication Association Creating a Space 2 CREATING A SPACE FOR “EVERY WOMAN” AT OPRAH.COM Oprah Winfrey has a personal fortune estimated at a half billion dollars (Tannen, 1998), is the head of a media empire that includes a perennially popular television talk show, an immediately prosperous magazine, a film and television production company, and an extremely busy fan-based web site. Her book club selections virtually guarantee immediate success for book and author. Guests on her show have become successful in their own right by virtue of their association with Oprah as a mentor and a friend (e.g. Dr. Phil McGraw). Yet, Oprah’s success certainly cannot be measured by her finances and economic impact alone. Her value lies in the degree of esteem with which she is held by millions of women throughout the world. Her primarily female audience describes her as a trusted friend, a confidant, and an ally. Winfrey interacts with audiences both present in studio audiences and tuning in through the media alike, allowing insight into her own life and establishing a rare sense of intimacy (Haag, 1993; Tannen, 1998). Winfrey is perhaps unique in that she has inspired this sense of connection across multiple mediated channels; her image, established in the mass medium of television, can extend to the more interactive realm of the Internet through the conversations and discussions taken up by her fans on Oprah.com. In this article, we analyze the ways womeni participate in this on-line forum, in an attempt to understand how such participation is symbolized and what it represents for practical notions of interpersonal relationships, communication and community as well as more abstract academic theorizing on the virtues of virtual relationships for women. Creating a Space 3 The Oprah.com web site is fascinating to observe. Women visit it to seek support from others, to give advice, to voice opinions or describe an experience, and to come together as a community with Oprah fan hood as a common thread. In this work, we study the formation of relationships and community in this particular area of cyberspace through analysis of written contributions of web site users. We also assess the characteristics and qualities of the space itself, the opportunities it affords in providing a forum for women as well as the constraints it imposes by virtue of its commercial and structured form. What results is somewhat unique to the “Oprah experience” but also points to common themes as well as tensions around the notions of communities as they exist both on and off line for women. Thus, three important questions drive this study: (1) How do women participate, how do they form relationships on Oprah.com? (2) What are the cultural and social bases for their participation? (3) Are spaces such as Oprah.com important sites for women? The theoretical underpinnings of this investigation come from social constructionist approaches to communication that put communicative practices at the center of meaning making. While the medium for the practices we analyze is the Oprah.com web site, the focus for our study is how participation in this particular community is enacted in cyberspace and what consequences attributed to their on-line participation. While the strategy of media convergenceii plays an important role in the structuring of Oprah.com and the marketing value assigned to the site, a discussion of the political economyiii of this community is beyond the scope of this paper, and is taken up in a related study (This author, 2001). For our purposes here, we wish to acknowledge that “O Place” on Oprah.com has been created as a unique media form that both extends Creating a Space 4 and generates other Oprah Winfrey media holdings. The on-line venue is marketed and commodified as a community in which members can and must invest. The marketing of Oprah’s image as well as her style of connection and intimacy helps to make the site possible and plausible as a site for community formation and more or less real to those who travel there. The importance of defining and naming sites such as Oprah.com “communities” is at the center of much CMC scholarship on the virtues of virtual communities. While we touch briefly on the debates about the authenticity of such communities, our focus is directed more toward the interpersonal, social and cultural premises for interaction in this virtual space. In the sections that follow we detail the theoretical and methodological considerations that inform our analysis. Searching for Community: Theoretical Considerations Jones (1998) and Wood and Smith (2001), among others, have noted that the idea of virtual community and the quest to find it remains primarily an academic venture. While we would not argue with this claim, we feel that the academic focus on the concept does not warrant its dismissal. The idea or ideal of community remains critical for those who theorize and analyze communicative practices as well as those who participate in them, whether on or off line (Ashcraft, 2001; Depew & Peters, 2001; Rothenbuhler, 2001; Shepherd, 2001). The formation of relationships and community in cyberspace has been the focus of a large body of interdisciplinary research concerned with the relative stability or fluctuation of these concepts and the degree to which they have promoted social Creating a Space 5 interaction and social change. The debate over the nature and consequences of what “counts” as relationship or community in computer-mediated communication generally results in some predictable conundrums: between the unitary body located in physical space and the fragmentation of identities in cyberspace, between the virtual space of information and the material space of day-to-day reality, between the authentic and the imaginary spaces of community, between spaces of anonymity, isolation, difference and hierarchy and affiliation, relationship and equanimity. It is toward the latter dimensions of community (affiliation, relationship and equanimity) that Interpersonal Communication research has focused, implying both explicitly and implicitly that intimacy, supportive social ties and community are highly valued goals to be achieved (Burgoon, 1995). Adams (2001) observes “although intimacy and close social ties may be desirable qualities for a community, they are neither necessary nor sufficient conditions for the structure and functions of communities” (p. 39). While Adams’ argument is directed at communities located in physical space, where people are often born into communities or join them, research and theory on cyber communities has perhaps explicitly relied on interpersonal relationships as criteria for community both because of the voluntary nature of most social interaction on-line as well as the reliance on relatively limited and relatively homogenous means for communicating. To widen the scope of analysis of communities, rather that limiting the focus to their veracity, Baym (1998) describes other important factors that help to determine how meaning is made of on-line communities and how they become meaningful. Baym (1998) provides a set of preexisting structures that are useful for analyzing an on-line Creating a Space 6 community’s style (the scaffolding that helps provides a context for interaction): external contexts (the cultural contexts that shape people’s use of and meanings given to their online interactions), temporal structure (synchronous or asynchronous, fleeting or long term), system infrastructure (physical configurations, system adaptability, and level of user friendliness), group purposes (whether discussing particular topics, providing advice, or participating in a community of Oprah fans), and participant characteristics (ranging from the size of the group to members’ experience with and attitudes toward new technologies). Moving from a focus on the structure and processes through which virtual communities articulate themselves, a crucial concern for feminists and others researching gender, technology and community is whether, how or where women’s lives have been improved as a result of the information revolution. Here, as in many debates about CMC and community, the debate tends toward utopian and dystopian versions of the same story (Preston, 2001), with some feminist scholars reporting that not only are women underrepresented as users of the technology, but when they actually gain access to the technology they are immediately reminded that the “electronic frontier” is once again a male space. Scholars such as Herring (1996), Spender (1995), and Kramarae (1997) report that women post (to listservs) in a “different voice” from men, and while it is notable that both men and women can create “alternative” genders on-line (Bruckman, 1996; Turkle, 1995), negative stereotypes of women tend to be upheld (Kendall, 1996; Kramarae, 1997). Other feminists argue that gender switching online simply serves to reify previously existing gender categories of male and female, and little room for alternative constructions of identity (Danet, 1998) Creating a Space 7 On the other side of this debate are those feminists who see a natural link between women and on-line technology. They see the web as offering a metaphor for connection, for linking women to each other in ways that make them more powerful than they have ever been before. Where women link to each other’s sites, they are weaving a complex pattern of relationships and concerns that has historical precedent (Plant, 1995). This sentiment is expressed in the Women’sSpace Web article on the culture of cyberspace: There is a spirit of generosity in cyberspace which reminds us of the early days of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Networking activism and support are interwoven as we push ourselves to learn to work with the new electronic tools we are encountering. Together we anticipate a future where growing numbers of women can access and use the global connections to promote women’s equality (Women’sSpace Vol. 1(3), Web page). Ito (1997) attempts to move beyond this debate over the virtues of computer mediated communication (CMC) for women, to examine the “inter and intra-textuality of the Net as itself a social and political context where history, politics and discourse are being constituted” (p. 93). We extend her analysis of the text and use the context of the Internet as real social facts by looking at the ways participation is constructive of agency and community for women. Building Relationships On and Off Line: Methodological Considerations We look to the work of Lannamann (1994) and Fitch (1994) to build a theory of Creating a Space 8 interpersonal ideology which is, as Fitch says, “grounded in material practices, that is, language use; well informed, though not dominated by the possibilities of human interpersonal structures, including power imbalances…inclusive of the beliefs and values…that are so basic that they are rarely stated; and grounded in a firm notion of what is and is not cultural” (Fitch, 1994, p. 114) Such an interrogation of the operation of ideology in the interpersonal communication of Oprah-identified web site participants should prove instructive in tackling the question of how people create meaning when “positioned and responding to the positions invoked by others” (Lannamann, 1994, p. 145). We respond to Fitch’s question about how people “transcend differences in schemas, unknowable intentions, variable interpretations, conflicting goals, and other individual complexities to a degree that allows actions to be coordinated and relationships to form” (Fitch, 1994, p. 105) in order to provide some insight into the dynamics of the creation of and participation in virtual communities. Consideration of interpersonal dynamics in the formation of community also shifts the focus from community as a homogenous product of interpersonal interaction and toward interpersonal interaction as a product of community. Thus, interactions grow and are shaped by the community rather than vice versa. Adams (2001) notes that “A fascinating approach for interpersonal scholars might be the ways in which communities influence communication and relationships, as well as how the new communities are, in fact, built out of interpersonal relationships”(p. 39). A growing body of research has focused on the interpersonal dimensions of online interaction. Wood and Smith (2001) note that three broad perspectives characterize research on on-line relationships: the impersonal perspective, the interpersonal Creating a Space 9 perspective and the hyper personal perspective. The impersonal perspective portrays interaction on the web site as limited in terms of the amount of nonverbal cues and emotional content that could be exchanged. Proponents of this approach viewed computer mediated interaction as a poor substitute for face-to-face communication and those who spent a good deal of time on the medium as isolated and disconnected with more traditional forms of community. The interpersonal perspective views the relationship among the various media through which interaction occurs as more complex. One medium for interaction (e.g., computer mediated) does not necessarily substitute for another, but rather supplements or extend the forums in which people form and maintain relationships. Thus, while I might meet someone on-line, the fact that this is followed up by face-to –face contact neither presumes the authenticity of one form over another nor does it mean that I have moved in a linear fashion from impersonal interaction toward intimacy. The hyper personal perspective (primarily based on Walther’s 1996 research) observes that CMC promotes an environment where people are in more control over their self-presentation than in face-to-face interaction and thus are better able to express themselves and form relationships on-line than in “real life”. Walther (1996) highlights several conditions that allow this to occur: the sender can control how she wishes to present herself to others, the receiver can exaggerate the positive qualities of a potential relational partner, the asynchronous nature of the medium allows messages to be posted with more forethought than typically occurs in face to face interaction, and feedback can intensify the relationship in the absence of other nonverbal cues (Tidwell & Walther, 2002). Adapting these considerations to feminist conceptions of community, we see that Creating a Space 10 naming a community for women gives rise to forms of communicating that are expected and encouraged. Nonetheless, as Ashcraft argues, promoting an ideal for feminist community carries consequences: (a) it favors particular structures and procedures (e.g., minimal hierarchy, consensual decision making) to the exclusion of process and outcome considerations; (b) it promotes the rather bleak view that confrontation is inevitably disabling; (c) it depicts any form of power imbalance as an antifeminist development, thus equating feminist empowerment with absolute equality . . . At best, theoretical bias bounds our understanding of feminisms-in-practice (Mayer, 1995). At worst it brands feminist community an impossibility—an endeavor inherently destined for compromise (2001; 83). Although Oprah.com can be more accurately described as a space created for women, rather than a community devoted to a particular vision of feminism, Ashcraft’s concerns are instructive as we consider what assumptions structure the network and values presumed to be important to the women who participate there. Importantly, both Ashcraft (2001) and Adams (2001) place emphasis on the resonance between ideology and practice without forsaking the creativity and agency that arises from human interaction. Although perhaps neglecting somewhat the power dynamics and complexities of virtual communities in relation to those formed in other spaces, Rheingold’s (1993) oft quoted criteria for community: sustained conversation, public feeling and webs of interpersonal relationships apply to the relationships constructed at O’s Place. To these conditions, we would also add implicit criteria for credibility and membership through Creating a Space 11 knowledge of and appreciation for Oprah as a media personality, and, by extension the values and virtues she and her media outlets/enterprises promote. Even more implicit and important are the rules for membership according to social and cultural categories that apply in everyday physical spaces of community that are maintained in interactions on the Oprah message boards and chat rooms. Forms of social and cultural capital that cannot be seen in a text-based format are re-created to determine the credibility of one’s story, one’s place in the community and, particularly in this community, one’s right to offer advice to others in need. At this point, it is important to note that this project moves back and forth from the details of the everyday use and discourse on the Oprah chatrooms to the ways in which such use reflects larger social and cultural patterns of power. We utilize both descriptive and discourse analysis of the site and the messages posted in the message and chat rooms over an eight-month period. Our goal as participant/observers on the site is to extend previous analyses that focus primarily on the textual (conversation analytic approaches) or on the structural dimensions of Internet use. Methods and Procedures In the next section, we describe the site of our research and cyber fieldwork: the structure and space of “O Place.” The length and duration of our fieldwork in this site has been eight months. Our baseline was determined by previous assessments of the structure of communal space on the Internet, the intertextual nature of this particular community (members of the web site are also clearly fans of other Oprah related media), and the unique expectations of and commitment to virtual communities, given their Creating a Space 12 potential anonymity and ease of access for those who have a computer and a modem. In the study we address the central concerns of our research through ethnographic (descriptive and discursive) analysis of the Oprah web site, message boards and chat rooms. We base our interpretation of the participation and activity on the message boards on several ethnographic criteria: the usefulness of the activity for identifying and solidifying a sense of we-ness, depth of feeling the activity provides or provokes, and the amount of responses/interest the activity generates. Based on previous research of virtual communities (LeBesco, 1996; Mitra, 1997; Wood & Smith, 2001), we identify several characteristics of text-based communities that applied to this community as well, such as: (1) frequent discussions of rules for participation and/or membership, including discussion of punishment for violation of those rules; (2) the use of text-based emotional identifiers such as, :} (smile), Lol (laugh out loud) or rofl (roll on floor laughing), among others; (3) continuity and coordination of meaning based on threads of conversations; (4) flexibility in participation and commitment on the part of members, due to the ephemeral nature of the format and (5) some discussion of authenticity and/or verifiability that members were indeed who they represented themselves to be. This last criterion is much more important for “realitybased” communities (those that reflect upon or attempt to mirror activities and identities taken on in real life) than for fantasy-based communities, such as Multi User Dungeons/Domains or MUDs. Authenticity, however, remains an important criterion in both types of communities, whether one is authentically their real identity or their realfantasy identity, while the degree to which the community represents real-life activities and experiences is flexible in the ongoing interaction of each type of community as well. Creating a Space 13 As mentioned above, we spent eight months observing on line interaction, as well as occasionally participating on the Oprah.com site. We did not identify ourselves as researchers nor did we ask questions explicitly related to our project. As is the case with much “virtual” ethnographic work (LeBesco, 1996; Watson, 1997) the discourse posted on this site was/is considered to be public information, accessible to those who logged on or signed up (in the case of the chat rooms) to the site. Nonetheless, there are several ethical implications to collecting these stories and conversations for the purposes of research that need to be acknowledged. First, the site is intended as an interpersonal space for women to share their lives, therefore both reciprocity (of communication) and the personal nature of stories are implied. Second, as sometimes observers/lurkers and sometimes participants on the site, we intervened in the meanings that were created in on-line conversations, as well as in the meanings that we give to those posting/conversations in our research. Finally, our own positions as researchers/ethnographers as well as participants needs to be acknowledged. Although we participated on-line during the study, we did not and do not consider ourselves members of an Oprah “fan” community (thus compromising our implied authenticity as part of an on-line fan community). Our impetus for conducting this study was based on our curiosity about Oprah as a media icon and cultural phenomenon who had achieved her success by appearing “real” and “connected” to women's lives and stories. Still, other factors served to protect and preserve the anonymity of members of the site. Each person registering on the site was required to use a pseudonym (explicitly not a version of their real name) each time they logged on or wished to participate on Oprah’s site. Members also were informed of the rules of the site and the degree to which the messages they Creating a Space 14 posted became public information (i.e. were accessible to all who logged onto the site or entered a chat room). Before we participated on the message boards or in the chat rooms we spent some time observing the organizing topics and threads of conversation on the message boards. While the general themes that circulated in the discourse produced were generated by events and guests on Oprah's show or in the magazine, more specific references to relationships and community often emerged in the descriptions of how groups of women had met on-line and then formed local groups based on physical proximity (e.g. “spa girls”) or how members found support and nurturance through their on-line “buddies”. Several women referred to the members of Oprah.com as the only positive support they had in their otherwise busy and overwhelming and chaotic lives. Other women went to the site to solve or resolve specific issues in their lives (e.g. relationship problems) but nonetheless relied on the reciprocity of other group members to help them through their difficulties. Each of these uses of the site (and others mentioned elsewhere in the study) point to Oprah.com as an interpersonal gathering place, a community of women formed through their communication both for the purposes of reaffirming a togetherness among women who shared some common experiences and for seeking validation for themselves as individuals. Shepherd (2001) notes that interpersonal can mean both between, as in between “between persons” as well as together, as in the term intermingle He argues that “it is the latter sense of interpersonal that is key to understanding a useful postmodern sense of communication (p. 31). He goes on to observe that communion, the giving and partaking of the other through communication, is necessarily interpersonal. We build an Creating a Space 15 understanding of ourselves through the constant creation and recreation of relationships (as when inter means “together, one with the other”) (p. 32). It is with this understanding of the site's interpersonal potential for creating community that we based our participation on the site. Our interest was both in entering into and experiencing the interpersonal dimensions of the site, as well as observing the cultural basis for its popularity and use. To analyze the discourse, we downloaded the messages from the bulletin boards and recorded (via handwritten transcript) the interactions in the chat rooms. We used a representative sampling method that looked for key themes that appeared on the various message boards and chat rooms. To check for validity across our samples we first each downloaded what we thought was representative from the message boards and then compared samples from the discourse. Once we had identified what we thought were key themes from each board, we then assigned five message boards and one chat room to each author. In all, we downloaded or wrote down 106 transcripts of conversation from message boards and chat rooms. From the downloaded messages, we then searched for common and representative (i.e. understood by members of the community) terms for describing the space of the web site, common and representative terms for relating to or describing the experiences of others on the site, and actions and behaviors that occurred and were understood by members as contributing to a common sense of community. Analysis O Place: Description of Oprah’s Web Site O Place, on Oprah.com, is the official web site that links the major elements of the entertainment offerings of Oprah Winfrey. Many of the individual offerings on the Creating a Space 16 Oprah site revolve around the topic of understanding, improving, and establishing comfort with the self. Yet, this is often accomplished through interactions and the establishment and continuation of relationships among the largely female users of the site. Thus, with the help of Oprah and her fans, with whom the user can form a sense of rapport, one is invited to apply the strategies discussed on the television show, in the magazine, and on the web site to her own life to make it more fulfilling. There are ten categories of content listed on the far left of the site that help guide the user. These listings fit largely into two types, those about Oprah’s media offerings and those, which by title alone point to the “Live Your Best Life” theme. The ten featured categories on the Oprah site are: The Oprah Show, O The Oprah Magazine, Oprah’s Book Club, Oprah’s Angel Network, Your Spirit, Relationships/Dr. Phil, Food, Mind and Body, Lifestyle Makeovers, and About Oprah. Some of these titles are also used to organize the chat discussions (the focus of this research endeavor) that the user can access easily from the home page. The middle section of the home page for Oprah.com highlights selections from the various sections by showing pictures, providing brief descriptions, and offering direct links (rather than accessing them through one of the ten categories listed above). Oprah’s image is frequently featured, most likely as a familiar and welcoming symbol users readily identify with and feel favorably toward. The use of Oprah Winfrey’s image, often smiling and featuring warm hues, can help foster the perceived relationship web site users may feel they have with Winfrey and create a sense of participating with her and fellow fans through communication on the site. Creating a Space 17 The page also allows the user to access “This Week on the Oprah Show.” With a click on this button, day-to-day descriptions of the topics to be addressed on the upcoming shows of Oprah’s television program are given. This section also seeks input via a question posed to the user, one question per upcoming program. If the user clicks on this question and/or the accompanying thumbtack icon, she will “go” directly to the message board and chat area and specifically to this topic as it is situated on the page. For example, an upcoming program featuring Oprah’s expert on relationships asks “What would you like to ask Dr. Phil?,” and provides a dialogue box for the user’s response. Input from the user is also featured on the far right side of the home page in soliciting contributions to O, The Oprah Magazine. This button takes the user to a list of topics about which she is invited to “contribute your (her) ideas and experiences.” For example, on April 2, 2001, the topic was School Shootings and Bullies. Clicking on this topic takes the user to a page on which a brief blurb of the topic is provided (e.g., “In light of the saddening incident that took place in Santee, California recently, we at the Oprah Magazine want to know what questions you have about school shootings and bullies.”). A nearby box is provided with “Tell Us Your Story” as the only prompt. Thus, users are invited to post personal experiences or opinions and/or to ask questions about the topic. This interactive feature allows women to take ownership of the issues raised in the Oprah television show by voice their own life experiences via their submitted comments. Though on the message boards, unlike in the chat rooms, users do not reply to each other immediately, they still respond and refer to one another’s comments in their own postings. Relationships can be formed, therefore, in cyberspace through women’s responses to each other around a common topic. Creating a Space 18 Feedback Mechanisms on the O Place Web Page Many of the themes of this research project are evident in the structuring and content of the web site. First, contact and participation on the part of the user is highly sought after and often obtained. The site contains many easy-to-use feedback and opinion expression mechanisms, encouraging interactivity that is important to the degree of involvement one feels in the relationship with Oprah and fellow fans. Another function that interactivity affords is the application of information and concepts advanced in Oprah’s show, magazine, or web site to users’ own lives and experiences. Users of the Oprah site make sense of and utilize information provided by Oprah in their own potentially diverse and unique fashions. Interactivity also allows for the fostering of community and mutual support between and among women who chat on the message boards provided by the site. Community is formed virtually across space and time through conversations that take place on the Oprah web site, with mutual support and teamwork encouraged through such language as: “Have you completed Dr. Phil's 10week plan? Stay on track with your weight loss goals—return to this board for continued support and motivation!” or “If you're on the road to pursuing your passion and need encouragement, visit our Finding Encouragement chatroom.” The consistent categories of content, Oprah’s Angel Network, Your Spirit, Relationships/Dr. Phil, Food, Mind and Body, and Lifestyle Makeovers, are all clearly targeted toward women and reveal notions about the types of issues in which Oprah fans (mostly women) are most interested. Identifying and discussing people who have “performed miracles” (The Angel Network), nurturing one’s spirit (Your Spirit), asking Creating a Space 19 an expert for advice about relationships (Relationships/Dr. Phil), and exchanging recipes (Food) are all typically viewed as primarily concerns of women according to marketers. Likewise, the feedback mechanisms mostly take a form often used in recovery programs, such as writing in a journal, “talking it out” with others, or finding comfort and support in others. Message Boards and Chat Rooms The bulk of content provided by the site’s creators that helps structure the conversations women have around the site is largely “self-help” or self-improvement in nature. Though there is a focus on the self, however, self-improvement as defined by the strategies and content advanced on Oprah’s website is not a solitary pursuit. Rather, the path is paved, in part, through tapping into the strength and resources of others and through communicating to others one’s feelings and experiences. In short, the relationships one forms are frequent sources of support and guidance in the process of self-help. We turn to the broad questions of how women use information from the site and what functions relationships that build from the site serve in the latter part of our analysis. The main focus of this article is an in-depth, qualitative analysis of discourse generated by and exhibited on Oprah.com. Yet, we also attempt to place that qualitative analysis into a larger context by providing a brief quantitative overview of the numbers of messages that were posted under each folder during a specified amount of time. Thus, the appended table and its description here intend to provide a sense of the scope and magnitude of the interactions on Oprah.com that may not be apparent in an analysis of specific exchanges and postings. Creating a Space 20 Analysis of the activity occurring over approximately a one-month period of time on the Oprah.com website suggests that, in general, the site is rather active. The table demonstrates the number of postings included in each of the folders used to organize input on Oprah.com from April 2 to May 2, 2001. These figures were collected from the site on four different dates (April 2, April 11, April 20, May 2) in order to determine the growth in numbers of postings for each topic over time. The month of April to May was chosen at random to represent a typical month on the website. Though a longer period of time would have provided an interesting view of the activity on Oprah.com, the one month period chosen was deemed sufficient for our purposes here, to simply provide an overview of the typical context in which the discourse that we analyze in the article was occurring. The message boards and chat options appear to be used fairly frequently, with recurrent conversations occurring between and among users, a portion of which we’ve included in our analysis below. The topics of discussion on the message boards that generated the largest numbers of postings were: Ideas Exchange under the heading Oprah’s Angel Network, Remembering Your Spirit and Favorite Quotes under Your Spirit, Simplify Your Life under Lifestyle Makeovers, and One Simple Change under Mind and Body. Each of these topics had garnered well over 1000 discussions among users of the site and clearly emerged as those that inspired the most conversation. The most popular topics have much in common. Each invites users to discuss specific strategies and techniques used to retain physical and psychological well-being. Each involves self-help, through attention to spirituality (Remembering Your Spirit), ways to relieve stress and retain order in life (Simplify Your Life), and healthful diets, non- Creating a Space 21 smoking strategies, and exercise efforts to maintain physical health (One Simple Change). It is not surprising that these useful, practical guidelines shared among users of the site would be the most common source of exchange. The popularity of Favorite Quotes, somewhat similarly, suggests users also lend words of wisdom via statements made by famous others, in addition to reporting their own personal experiences. The remaining topic that inspired well over 1000 discussions in one file and several hundred in a series of additional files centered on Oprah’s Book Club. One month’s activity on the site reveals a high frequency of discussions generated around this topic, thereby attesting to the impressive power of Oprah’s Book Club on the reading and purchasing behaviors of readers and on the publishing industry. Over 1500 Book Suggestions had been posted by website users by 5/2/01 with the number of postings in this file increasing by 120 in the span of one month. Users were clearly also very interested in having a conversation about children’s books; we observed a growth of 120 postings on this topic between 4/2 and 5/2/01. Hundreds of Oprah.com website users also discussed inspiration they had received from authors and their works (What Authors Have Inspired You?) and created a dialogue around Building Your (Their) Own Book Club. Participation and Criteria for Membership in Virtual Communities Participation is at the center of our analysis of the ways in which a virtual community is created and maintained around the media image of Oprah. In the remainder of this study, we analyze the ways people (primarily women) coordinate their actions to create and uphold meaningful membership in the Oprah community as a valid cultural Creating a Space 22 form. We identify several rituals of activity based on the repetition and frequency with which they occur as well as the salience that they posed for the members of the community. Themes of self-responsibility, offering and receiving advice or support, affirmation, and marking or regulating community each reflected the ways women participated on the message boards and in the chat rooms. Claiming Responsibility for What We Can Change In line with Oprah’s philosophy of transforming communities through selftransformation, a major way of participating on the message boards and in the chat rooms was through claiming responsibility for one’s own actions. As the majority of the messages indicate, “claiming,” “naming,” but not “blaming” is key rules for participating. Members chastise each other for not “owning your own stuff” and “tak[ing] responsibility” for weight gain, relationship problems or (most importantly) reporting back to the community about their progress. Much of the discourse around taking responsibility could be directly linked to the underlying theme of Oprah’s show, magazine and web site, taking charge and changing your life. In particular, this theme referenced the popular 12-step program of overcoming addiction through reliance on a higher power. These contradictory discourses (taking responsibility for self versus reliance on a higher power beyond your control) are reflected powerfully in US culture generally and are discussed in more detail later in the article. Asking /Giving Support or Advice. A typical activity for many of the participants on the sites that also affirmed the community and the connection among members was asking for and receiving advice and Creating a Space 23 support. This activity occurred frequently and was replicated on all the discussion groups, whether on spirit, relationships, or the general talk around the show. While many threads could be cited on all the message boards, one from the “Simplify your life” board exemplifies the importance that both asking for and receiving advice and support served for the community. After one woman posted a message asking for relationship help, she received many responses that both affirmed her struggle to distance herself from a bad relationship and provided advice and support for “going on” without him. The following excerpts illustrate the ways these women communicated an empathetic understanding of relational difficulties while urging the woman with the problem to acknowledge her own “addiction” and seek help from a higher power: Dear Brokenhearted girl!!iv Listen to what all frosting1112 had to say to you today… she is wise and what she said is right-on!! I, too, think your ex-boyfriend is trying to keep you hanging on!! Guys do this all the time. They will break your heart…knowing that you love them. and then feel some sort of…male"thing" when you cry about them.. It makes me sick!! Girl.. Maybe it's time you just start setting some of those boundaries for yourself!! Your pain is very genuine to me. I know and can feel threw the computer and threw your words that you need help . . .but… if you keep focusing on him and never really try working this out for yourself. You are going to continue to stay sick!! And, you are sick . . . he is like a drug for you. YOU got to make a step…toward recovery!! He is an addiction!! (Phyllis g) Hi again. Hope things are getting better for you girl.. You still sound a little confused and upset to me.. I hope and shall keep you in my prayers. And know God will bring you peace if you let him!! (Frosting 1112) I wanted to thank you all for you beautiful reply. I could only hope to be as beautiful as the sweet spirit that I know from all of you!! (Brokenhearted) Creating a Space 24 While the responses from other members of the community indicated their support, the underlying message for Brokenhearted was that it was up to her to ”recover” from her addiction. Her response indicates both that she agrees with the “diagnosis” of her relational disease and that she wants to validate the connections she feels with other participants by responding to each one: I think your words will help. No Phyllis, you haven't offended me. Your words are the truth. I will try to break free. You are absolutely right about him being my drug. I feel as if I had to get away from him, cold turkey. Just like that he was gone. Frosting1112, I still want to write him a letter, but I have already sent him e-mails. I have even put poems in them that say it all: exactly how I feel. I also have asked him face to face why he left me. . Yes I made the unwise step to sleep with him a few days ago, and it was clear that we both had different intentions . . . He says he wants me to be strong again like I was in the beginning of our relationship, six years ago. He says he wants me to be independent from him. He wants me to have lived a life without him. After that he thinks he might want me back. I truly believe he wants the best for me. He thinks I need to break free from him to save myself. I know, Phyllis, you were right about him making all the decisions. That is true, I am afraid I made that happen by always making him so much more important than myself. I said to him, I will always have hope of us getting back together in the future. He knows that. A friend said to me that if he could see me being stronger and even with other guys, he would miss me and come back. You see, he betrayed me once before. I forgave him. I guess that made him stop respecting me. I feel now as though I made all the mistakes, while I know all I did was love him as purely as I could. Is that wrong? I am afraid.... Bye, Love, your Brokenhearted friend... Creating a Space 25 The rhetoric of addiction and recovery was present in all the message areas, whether the subject was weight, relationships or, as in the case of this board, simplifying one’s life. The movement from doing it on your own (as in the discourse of Dr. Phil’s contributions on the show and in the magazine) to giving up control and giving yourself over to a higher power is consistent with the contradictory cultural messages that pervade contemporary media and self-help literature. The ways women in particular utilize selfhelp literature and participate in self-help communities have been documented elsewhere (see, for example, Cooks & Descutner, 1994; DeFransisco, 1995; Grodin, 1995), however, for our purposes, it is useful to note that the cultural premises for self-help talk (“addiction” and “recovery” through a higher power) were understood and shared among participants on most of the message boards. Celebrating Victories and Sharing Struggles. Women participated frequently on the message boards to affirm others “struggling along the path” and to ask for affirmation from other members of the community. Often the women would discuss the ways that their relationships in physical space had let them down, and would look for or offer validation that members of this community would not let them down. As “O Place” member Faithstep put it, I truly enjoy reading about peoples little victories. A whole bunch of those add up to a big result. I thank you all for sharing your hearts. And if you are struggling I want to hear that too. The world is too full of fair weather friends. I do not think there is any such thing as overpraising or being too nice. While Faithstep (and others) cited a higher power or some other source of strength, they also thanked women on the Oprah message boards or Oprah herself for helping them get Creating a Space 26 through the really hard times. On the official messages boards for spirit and for simplifying your life, many of the women told stories of hardship: of poverty, abuse, hard work and difficult emotional times in their lives. They connected their stories with others on the site and on the show, and to Oprah herself. On these boards in particular, Oprah was often represented as the center or the core values for a community marked by self-empowerment, selftransformation, good will and friendship. Oftentimes, when the discussion in the chat rooms or on the message boards went into areas not recognized as the official format of the web site or as appropriate topics for the community, the members would pull the discussion back to a safer theme, either through directing the member back to the lists of rules for participation, through discussion of what topics were valued by the community or through the use of humor. The following discussion thread from the Lifestyle Makeover chat room on the official site occurred after several members were engaging in a conversation with cybersex innuendos: When they said that this was the lifestyle makeover room, I didn’t think they were talking about this kind of lifestyle . . . (Mirror) LoL Mirror. (Judyp) (Others respond with the same character indicating, “laugh out loud”) I just snorted my tea all over the keyboard . . .(Asparagus) That’s a frequent problem. I NEVER eat when I’m chatting with these guys. (Gingerspark) I’d rather have food than sex, or cybersex, anyway. (Mirror) If I wanted cybersex I’d look elsewhere. This room is for bonding with friends. (Brownieb) Creating a Space 27 How could you do that anyway? You don’t even know what the person looks like . . . (Jerrydo) Yeah, they could be ugly or have cooties (Mirror). Ooh cooties. Lol. (Asparagus) [Others respond with rofl “roll on the floor laughing” or Lol] After this exchange (in which one of the authors participated) the discussion went back to a conversation about bizarre diets, eating disorders and stomach distress, which led to another discussion of potential remedies. The suggestion of and even advertising for products deemed helpful in many situations (here for the relief of gastrointestinal distress) occurred frequently in chat rooms and on message boards and will be addressed in more depth later in the paper. What is important to note, in the context of this exchange, is the subtle guiding of the topic back to one that was sanctioned by the web site and by the format of this particular chatroom. Marking/Regulating Community Tracking Mobile Communities Messages indicating movement through the virtual spaces of the community allow others to track both their movement/progress through the program, as well as keep informed about members. One of the message boards actually framed participation in terms of where a member was in progress toward the goal of losing weight. Thus, a member would post on the Week 5 bulletin board, if that indicated her progress in the plan. Members would regulate the postings by asking others to limit their posts to the particular week they were on. On Week 10 bulletin board, for instance, several members became upset when a few posts indicated the women were at an earlier stage in their Creating a Space 28 diets. This prompted an interesting response to the idea of when and where certain forms of talk could occur: I have been really searching my heart about what I want to say before I post. I feel a bit intimidated and have been even looking at that. I think I know now. If you don't believe I should be here posting (a week five person, then pass on, because this is my heart no matter what week I am in) I am not going away.(yes I am doing the work back there) (Skylark) These messages connote both agency (in movement through the relationship and diet plan) as well as reference to imposed movement to another message board. Another message reads: “It seems the powers that be have created a new board for those who are continuing past week 10. Check it out. That is where you will find most of us that have done the work. The address can be found on message #292. See ya there.” In these posts, the idea that someone is tracking progress assumes caring and affirms community, while at the same time noting the limitations of the current “space” for participation. The Difference that (Cyber) Space Makes While each of these ways of participating: taking responsibility for oneself, asking giving support or advice, affirming community, marking/regulating and maintaining community are mirrored or reflected in women’s participation in other forms of community life, it is important to note that cyberspace communities differ in terms of the continuity of conversations and in the fluidity of and commitment to participation. Members of virtual communities enter and exit the community with very little personal risk (that is, risk to their social presentation of self). Cyberspace preserves physical anonymity and to some extent on-line personas are protected by the different pseudonyms and identities they can adopt. Additionally, the formats of chat rooms are often marked Creating a Space 29 by discontinuity and fragmentation in conversation, which reduces expectations for commitment to sustaining threads of conversation for long periods of time. The format of the chat room itself is set up so that members are free (and to some extent encouraged) to leave at any time to pursue subjects in different rooms. This leads to a third difference in virtual communities: commitment to the conversation/topic and to other members participating in that conversation. While the conditions of anonymity, discontinuity and flexibility in time and space may lead to decreased responsibility to others in the community, these same conditions also can be said to actually increase participation in and commitment to the community. As we have seen in the previous section, members felt free to disclose very personal information that they might have felt less comfortable explaining in the physical presence of others. Moreover, some members noted that they actually expected and relied more on the support of their friends in cyberspace than they did on their “fair weather” friends and relatives in physical space. Social and Cultural Effects of Participation While critics of the Internet point to the tendencies of on-line technologies to isolate and potentially stratify communities, leading away from democracy, our study has shown another tendency. For women in the midst of the information age, life has never been more busy and difficult to manage. For many of the women in the Oprah community, time spent on the message boards and in the chat rooms was indeed time to connect with other members in a space that did not demand a rigorous reworking of schedules for face-to-face contact. These women could tune in and out of the community when they had the time and space to do so, a factor that gave them some control over their otherwise hectic lives and schedules. This important difference from interaction in Creating a Space 30 physical space meant for these women that they could “connect with friends,” as one chat room participant put it, without the stress and obligation that encumbered other forms of friendship and community. Whether such cyber-relationships replace or in fact supplement physical communal space is difficult to say and perhaps not relevant, as communication and other technologies increase contact with others (who have access) exponentially. The proliferation generally of possibilities for contact (if not, for some, of authentic relationships) becomes representative of the increasing fragmentation of self (Gergen, 1991) as well as self-in-relation-to community. To debate whether and if virtual communities pose a threat to the nature of relationships or of community presupposes the authenticity that then must necessarily only exist in physical spaces. Binaries such as the real or fantastic, veracity or inauthenticity become important when identities are called into question, whether on or off line. Another, and somewhat overlapping concern addresses the ways in which the cultural premises that shape the discourse on the message boards and chat rooms lead to the tensions between individualism/self sufficiency and relationships/community. Oprah’s appeal is that she represents the struggles of every woman through embodying the tensions of being a woman in today’s society: achieving ideals of wealth and independence while acknowledging the need for relationships and to connect with community. Conclusion Throughout this article we have referenced various discourses through which we assert that communities have been built in the cyberspace of Oprah.com. Yet, it has been Creating a Space 31 reasonably argued that on-line communities are nothing more than pseudo-communities, offering little in terms of commitment, reciprocity, or authenticity and a good deal of selfindulgence and fulfillment of individual needs and desires. Many scholars have debated both the criteria for on and off-line communities both in terms of their features and their consequences for communication and for our social world. Looking forward, Shepherd (2001) argues that contemporary communities must necessarily be based on promise or possibility, rather than on what is. He notes that “community has increasingly seemed an impossible achievement to us because we increasingly disbelieve the presence of the one condition required for its realization: the possibility of [interpersonal] communication…If we are to believe that communication is impossible in this world of uncommon individuals and indeterminate truth, then so too is community…We will not create community without allowing for faith in the possibility of inter-subjective transcendence through communication” (p. 33). The possibility for conceptualizing community in the wake of increasing access to and reliance on computer mediated communication, then, lies in the combination of communication (as the giving and receiving of embodied experiences) and faith that somehow we will grow and learn from this exchange. Oprah a symbol of authenticity (both essentializing and negating her blackness and femaleness), transcendence through struggle, acceptance, and ties to her community, and success (ascribing to and upholding the values of the most successful capitalist society on the planet) – serves as the touchtone for a community of women connected through their faith in transformation and change, even as they recognize the contradictions and challenges in their lives. Oprah’s leadership, her success, and her ability to connect in an intimate way with the stories and Creating a Space 32 lives of others have helped to position her as a central figure among a global community of women. At this point we return to the three important questions related the growing significance of female-oriented on-line communities which guided our research: (1) How do women participate, how do they form relationships on Oprah.com? (2) What are the cultural and social bases for their participation? (3) Are spaces such as Oprah.com important sites for women? Based on our analysis, these are some of the following ways that women participated and formed relationships on Oprah.com: offering and receiving advice or support, providing affirmation, promoting self-responsibility, and marking or regulating community via message boards and chat rooms. For many of the participants, the O Place web site gave them the opportunity to connect with other members of the O Place community who generally agreed with the social and cultural beliefs promoted by Oprah Winfrey and her various media outlets. There is no doubt that on-line spaces are important sites for women, but whether commercial sites like Oprah.com are the best models is yet to be determined. Schiller (1999) notes that although information resources are tools that can be utilized by anyone, anywhere, information commodities are limited in their ability to promote alternative ways of thinking about the world. Oprah.com is a beginning, but it remains to be seen whether on-line “commercial” spaces can be transformative sites by and for women. Limitations of the Study While much interpersonal communication research has analyzed the relationship between on and off line communication behaviors, the determination as to whether the Creating a Space 33 Internet inhibits, supplements or advances the off line relationships of the women who participate on Oprah.com is beyond the scope of this paper. Future research in this area could involve the women more directly and in greater depth by asking them to track their communication activity, both on and off line. This research would extend CMC research (e.g., Baym, 2001) that has examined the communication activity of students through diary tracking of their daily interactions on and off line. Such efforts would help to position the Internet as part of a larger network of media that shape interaction both through their intertexuality as well as through their different uses and effects. Other limitations of the current research are its ability to adequately examine the Oprah.com site as an extension of previous research on fan communities, as well as to take into account dimensions of parasociality at work at work in various members postings to or about Oprah which seemed to assume her accessibility as a friend, confidante, mentor, etc. Also, (and taken up elsewhere in our research), the larger political and economic effects of the convergence of Oprah Winfrey’s media holdings need to be as part of the structuring and processes that emerge in the course of building this community. Oprah.com: A space that women can relate through? Revisiting the questions that guided our study we see that women participate on Oprah.com as mothers, daughters, sisters, friends, consumers, pseudo-therapists, relationship experts, and fans. Perhaps due to the intimate and self-transformative nature of the site, the women who form relationships there rarely highlight differences across lines of culture, class, ability or sexuality. The apolitical or universal sense of sharing identities as women connects with Oprah’s refrain that she is “Every woman.” CMC scholarship on the nature and formation of on-line relationships and Creating a Space 34 communities resonates with some of what we have found in our participation in and observation of the Oprah.com site. Of the three perspectives on interpersonal interaction identified earlier, the impersonal, the interpersonal and the hyperpersonal perspective, our study supports the interpersonal perspective on on-line relationships in a number of ways. While we did not directly ask the participants on the site about their off-line relationships, such “talk” was often the content of their posts and thus would indicate an extremely full network of relationships. For women who had very busy off-line lives, the convenience of chatting or posting a message late at night allowed them to feel connected at a time when they might otherwise have been alone. For women who chatted across a variety of time zones and countries, the space offered a way to connect cheaply and conveniently in ways they could not accomplish otherwise without a great deal of inconvenience. As many of the women noted, posting a message or entering a chat room allowed them to analyze their problems and the problems of others, figure out their relationships and affirm their own and other’s struggles to change and improve their lives. It is important to note, however, that the perspective one takes toward relationships on-line has much to do with the characteristics of the virtual space where interaction occurs. Since the Oprah.com site attempted to deal with the real world issues and interests of women, the space was less one for acting out alternative sexualities and identities (e.g. Ito, 1997) than it was for women to extend or supplement the spaces for community in their real life. Thus, the structure of the site helped to shape the types of interactions that took place there as well as the types of people who became members. Categories for interaction such as “Simplify your life” are attractive to women who lead busy and complicated lives off-line and who go on-line to relate to others with similar Creating a Space 35 interests and concerns. This leads us back to the notion of on-line community, which a variety of CMC research on the topic has indicated may be based on factors such as anonymity, accessibility, shared interests and support. While not pertaining to all on-line sites for participation and membership, certainly these are characteristics that make such spaces attractive to members. Still, however, the question persists as to whether Oprah.com could be considered a space for women? Preston’s observations about the role of postmodernism as depicting communication in the information age perhaps hints at the nature of the question as well as the stakes behind it: “The term postmodern poses as many issues about the how (how to describe, represent, etc.) as it does about the what (the key content or contours or facts) of social and cultural change” (2001; p. 80). Indeed, research on community and CMC has evolved from a need to document virtual community as a space for social interaction on the Net, to a focus on the requirements for the authenticity or validity of such community. Thus, the connections between how such moments of connection occur and what effects emerge from those relationships are less relevant than the documentation of their relevancy for some larger Community. For those concerned with the consequences of on-line community, the question of what should (virtual) communities do deserves a response located in when and how women (and others) create a space for building and affirming both their on and off-line lives. This study has been an attempt toward locating those spaces. Creating a Space 36 Table. Charting Activity on Oprah.com’s Website Discussion Groups. Number of postings Date in 2001 Topic (provided by the website) 4/2 4/11 4/20 5/2 The Oprah Show April Broadcasts May Broadcasts Information from Past Shows Here! 5 0 0 918 10 0 0 941 20 0 0 967 0 4 0 1001 Oprah Magazine April Issue May Issue Looking for Information? Oprah’s Cut 7 0 758 0 7 0 759 0 7 1 765 0 7 1 0 7 Oprah’s Book Club Icy Sparks What Authors Have Inspired You? Recommended Kids’ Books Book Suggestions Build Your Own Book Club Non-Book Club Books Seen On Oprah 143 0 364 879 1456 617 0 239 212 0 362 889 1480 629 0 239 254 0 377 905 1505 635 0 245 327 0 416 919 1576 645 0 254 Oprah’s Angel Network Inspired by the Use Your Award “Use Your Life Award” Kindness Chain In Need of Prayer Making a Difference Ideas Exchange 0 75 170 237 221 373 959 0 94 173 253 258 390 1000 0 98 174 257 300 399 1011 0 102 175 271 326 412 1029 Your Spirit Remembering Your Spirit Gratitude The Best Part of Today Random Acts of Kindness Meditation Favorite Quotes 1385 664 301 133 93 802 1564 1726 1906 775 848 904 319 326 333 152 162 176 113 127 134 849 882 1071 Continued on next page. Creating a Space 37 Table. Charting Activity on Oprah.com’s Website Discussion Groups. Number of postings Date in 2001 Topic (provided by the website) Relationships-Dr. Phil McGraw Getting Straight with Your Weight Getting Real with Your Relationship Relationship Rescue Family Relationships 4/2 4/11 4/20 5/2 0 9 0 2 7 8 9 0 11 0 2 7 8 9 0 11 0 2 7 8 9 0 11 0 2 7 8 9 5 4 4 70 193 25 0 0 7 4 4 71 200 25 0 0 8 4 4 74 208 29 0 0 10 4 4 86 219 28 0 5 Lifestyle Makeovers Lifestyle Makeover Weekly Challenge Lifestyle Makeover Pursuing Your Passion Simplify Your Life 0 11 17 0 1078 0 12 17 1 1105 0 14 17 1 1125 0 15 17 1 1149 Oprah Winfrey Presents The Movie: Amy and The Book: Amy and 116 16 117 16 118 16 121 16 Mind and Body Your Mind Your Body Spa Girls One Simple Change 9 13 3 1642 9 9 9 13 13 14 3 3 3 1689 1735 1800 Continued on next page. Food Oprah.com Recipe Review Recipe Exchange Healthy Eating We Want to Hear from You Cooking Questions? Art’s Recipe Box Recipe Review: Spa Breakfast Creating a Space 38 Table. Charting Activity on Oprah.com’s Website Discussion Groups. Number of postings Date in 2001 Topic (provided by the website) 4/2 4/11 4/20 5/2 In the News Science and Health News Sports News Election 2000 Headline News Good News! Hometown News Political News Business News 58 9 365 134 48 30 176 17 63 9 366 145 51 30 181 17 65 9 367 150 54 30 186 18 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Journal Message Boards Community Gratitude Daily Journal Gratitude 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 25 157 50 Creating a Space 39 References Adams, C. H. (2001). Prosocial bias in theories of interpersonal communication competence: Must good communication be nice? In G. J. Shepherd & E. W. Rothenbuhler (Eds.), Communication and community (pp. 37-52). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Addison, J. & Hilligoss, S. (1999). Technological fronts: Lesbian lives “on the line”. In K. Blair & P. Takayoshi (Eds.), Feminist cyberspaces: Mapping gendered academic spaces (pp. 21-40). Stamford, CT: Ablex. Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origins and spread of nationalism. London: Verso. Ashcraft, K. L. (2001). Feminist organizing and the construction of alternative community. In G. J. Shepherd & E. W. Rothenbuhler (Eds.), Communication and community (pp. 79-109). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Baym, N. K. (1998). The emergence of community in CMC. In Jones (Ed.), Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting Computer-Mediated Communication and Community (pp. 35-67). Thousand Oaks: Sage. Baym, N. K. (1995). From practice to culture on Usenet. In S. L. Star (Ed.), The cultures of computing (pp. 29-52). Oxford, U.K. : Basil Blackwell. Beniger, J. (1987). Personalization of the mass media and the growth of pseudocommunity, Communication Research, 14(3), 352-371. Blair, K. & Takayoshi, P. (1999). Introduction: Mapping the terrain of feminist cyberspaces. In K. Blair & P. Takayoshi (Eds.), Feminist cyberspaces: Mapping gendered academic spaces (pp. 1-20). Stamford, CT: Ablex. Bruckman, A. (1996). Finding one’s own space in cyberspace. Technology Review, 99(1), 48-55. Burgoon, M. (1985) A kinder, gentler discipline. Feeling good about being mediocre. In B. Burleson (Ed.),Communication Yearbook 18 (pp. 464-479). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Burgoon,M. 1995 A kinder gentler discipline: Feeling good about being mediocre. In B. Burleson (Ed.), Communication Yearbook 18 (pp. 464-479). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Cooks, L. M. (2001). Negotiating national identity and social movement in cyberspace: Natives and invaders on the Panama-L listserv. In B. Ebo (Ed.), Cyberimperialism? Global relations in the new electronic frontier (pp. 233-252). Westport, CT: Praeger. Cooks, L. M. & Descutner, D. (1993). Different paths from powerlessness to empowerment: A dramatistic analysis of two eating disorder therapies, Western Journal of Communication, 57, 494-514. Creating a Space 40 Cooks, L. M., & Descutner, D. (1994). A phenomenological inquiry into the relationship between perceived coolness and interpersonal competence. In M. Presnell & K. Carter (Eds.) Interpretive Approaches to Interpersonal Communication (pp. 247268). New York: SUNY Press. Curtis, P. & Nichols, D. (1993). MUDs grow up: Social virtual reality in the real world. (fttp://ftp.parc.Xerox.com:/pub/MOO/papers/MUDsgrowup.txt). Danet, B. (1995). Playful expressivity and artfulness in computer mediated communication. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication 1(2). http://207.201.161.120/jcmc/vol1/issue2/genintro.html. DeFrancisco, V.L., & O’Connor, P. (1995). A feminist critique of self-help books on heterosexual romance: Read ‘em and weep. Women’s Studies in Communication, 18(2), 217-277. Depew, D. & Peters, J. D. (2001). Community and communication: The conceptual background. In G. J. Shepherd & E. W. Rothenbuhler (Eds.), Communication and community (pp. 3-22). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Dietrich, D. (1997). Re-fashioning the techno-erotic woman: Gender and textuality in the cybercultural matrix. In S. Jones (Ed.), Virtual culture: Identity & communication in cybersoicety (pp. 169-185). London: Sage. Ebo, B. (2001). Cyberglobalization: Superhighway or superhypeway. In B. Ebo (Ed.), Cyberimperialism? Global relations in the new electronic frontier. (pp. 1-8). Westport, CT: Praeger. Fitch, K. L. (1994). Culture, ideology, and interpersonal communication research. In Deetz, S. A. (Ed.), Communication Yearbook 17 (pp. 104-135). Thousand Oaks: Sage. Foster, D. (1997). Community and identity in the electronic village. In D. Porter (Ed.), Internet Culture (pp. 23-38). New York: Routledge. Gergen (1991). The saturated self: Dilemmas of identity in contemporary life. New York: Basic Books. Grodin, D. (1995). Women reading self-help: Themes of separation and connection. Women’s Studies in Communication, 18(2), 123-134. Haag, L.L. (1993). Oprah Winfrey: The construction of intimacy in the talk show setting. Journal of Popular Culture, 26 (4), 115-122. Hamilton, J. C. (1999, December 3). The ethics of conducting social science research on the Internet. The Chronical of Higher Education, pp. B6-7. Haraway, D. (1991). Simians, cyborgs, and women: The reinvention of nature. London: Free Association Books. Haraway, D. (1985). A cyborg manifesto: Science, technology and socialist feminism in the late twentieth century. In Simeons, cyborgs and women.(pp. 127-148). New York: Routledge. Herring, S. (1996). Posting in a different voice. Gender and ethics in CMC. In C. Hess(Ed.), Philosophical perspectives on Computer-Mediated Communication. Creating a Space 41 Albany: SUNY Press. Ito, M. (1997). Virtually embodied: The reality of fantasy in a multi-user dungeon. In D. Porter (Ed.), Internet Culture (pp. 87-110). New York: Routledge. Jones, L. (2000). “The Mightiest Names in American Television are Launching a Channel for Women.” The Independent. 30 January. Jones, S. (1998). Information, internet and community: Notes toward an understanding of community in the information age. In S. Jones (Ed.), Cybersociety 2.0 (pp. 1-34). Thousand Oaks: Sage. Kendall, L. (1996). MUDder? I hardly know’er! Adventures of a feminist MUDder. In L. Cherny & E. R. Weise (Eds.), Wired women: Gender and new realities in cyberspace (pp. 207-223). Seattle, WA: Seal Press. Kramarae, C. (1998). Feminist fictions of future technology. In S. Jones (1998) Cybersociety 2.0. (pp. 100-128). Thousand Oaks: Sage. Kramarae, C. (1998). Feminist fictions of future technology. In S. Jones (1998) Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting computer-mediated communication and community. (pp. 100-128). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. LeBesco, K. (1998). Revolting Bodies? The on-line negotiation of fat subjectivity. Doctoral dissertation. University of MA, Amherst. Lannamann, J. L. (1994). The problem with disempowering ideology. In Deetz, S. A. (Ed.), Communication Yearbook 17 (pp. 136-147). Thousand Oaks: Sage. Lannamann, J. 1995. The Politics of Voice in Interpersonal Communication Research.” Pp. 114-134 in Social Approaches to Communication, edited by Wendy LeedsHurwitz. New York: Guilford Press. Martin, C. (2001). “Relationship Revolution: Internetworking, Not Net, is Key.” Advertising Age. 5 March. P. 22. Mayer, A. M. (1995). Feminism-in-practice: Implications for feminist theory. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association. Nakayama, T. & Martin, J. (1999). Introduction: Whiteness as the communication of social identity. . In T. K. Nakayama & J. N. Martin (Eds.), Whiteness: The communication of social identity (pp. vii-xiv). Thousand Oaks: Sage Mayer, 1995. Miller, L. (1995). Women and children first: Gender and the settling of the electronic frontier. In J. Brooks & I.A. Boal (Eds.), Resisting the virtual life: The culture and politics of information (pp. 49-57). San Francisco: City Lights. Mitra, A. (1996). Nations and the internet: The case of a national newsgroup, ‘soc.cult.indian’. Convergence, 2(1), 40-75. Mitra, A. 1997. Virtual commonality: Looking for India on the internet. In S.G. Jones (Ed.), Virtual Culture (pp. 55-79). London: Sage. Morse, M. (1997) Virtually female: body and code. In J. Terry & M. Calvert (Eds.), Processed lives: Gender and technology in everyday life (pp. 37-65). London: Routledge. Creating a Space 42 Neff, Jack. (2001). “IVillage May Not be Big Enough for Both of Them.” Advertising Age. 12 February. P. 24. O’Leary, N. (2001). “O Positive.” Brandweek. 5 March. Peck, M. E. (1987). The different drum: Community making and peace. New York: Simon and Schuster. Plant, S. (1995). The future looms: Weaving women and cybernetics, Body and Society, 1(3-4), 45-64. Preston, P. (2001). Reshaping communications. London: Sage. Rheingold, H. (1993) The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. New York: Addison-Wesley. Rose, M. (2001). “In Oprah’s Empire, Rivals are Partners. Wall Street Journal. 3 April. Rothenbuhler,E. W. 2001. Revising communication research for working in community. In G.J. Shepherd & E.W. Rothenbuhler (Eds.), Communication and community (pp. 159-179). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates. Schiller, D. (1999). Digital Capitalism. Cambridge: MIT Press. Shepherd,G. 2001. Community as the interpersonal accomplishement of communication.. In G.J. Shepherd & E.W. Rothenbuhler (Eds.), Communication and community(p. 25-36). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates. Spender, D. (1995). Nattering on the net: Women, power and cyberspace. Melbourne: Spinifex. Stelarc. (1996). From psycho to cyber strategies: Prosthetics, robotics and remote existence. Canadian Theatre Review, pp. 19-42. Tannen, D. (1998, June 8). Oprah Winfrey. Time, 151 (22), 196-199. Thompson, S. (2001). “Slim-Fast Sets Out to Beef Up Web Club.” Advertising Age. 3 April. P. 26. Tidwell, L. & Walther, J. B. (2002). CMC effects on disclosure impressions and interpersonal evaluations. Human Communication Research, Turkle,S. (1995). Life on the screen: Identity in the age of the internet. New York: Simon and Schuster. Turow, Joseph. (1997). Breaking Up America : Advertisers and the New Media World. Chicago : University of Chicago Press. Wakeford, N. (1997). Networking women and grrrls with information/communication technology: Surfing tales of the World Wide Web. In J. Terry & M. Calvert (Eds.), Processed lives: Gender and technology in everyday life (pp. 52-65). London: Routledge. Walther, J. B. (1996). CMC: Impersonal, interpersonal and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23(1), 3-43. Watson, N. (1997). Why we argue about virtual community: A case study of the Creating a Space 43 Phish.net fan community. In S. Jones (Ed.), Virtual culture: Identity and community in cybersociety (pp. 102-132). London: Sage. Women’sSpace http://www.softaid.net/cathy/vsister/w-space/vol13.html. Wood, A. F. & Smith, M. J. (2001). Online communication: Linking technology, identity & culture. Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. Creating a Space 44 Endnotes i No definitive analysis of the gender of those who posted or chatted on Oprah.com was possible. We relied on fairly ambiguous cues, such as nicks or pseudonyms, pronouns, as well as references to activities, identities and relationships to try to determine the percentage of women who participated on the site. ii Media Convergence is the synergistic strategy of using a variety of media to get the most exposure/saturation for a product. In this case, Oprah’s image is communicated via mass media such as television and print as well as the Internet. iii Preston (2001) notes that much of the work of political economists focuses on exploring how technological economic and political factors have brought about fundamental but interrelated sets of changes in both (1) the media of public communication and (2) in the broader/overall fabric of socioeconomic and political processes in contemporary capitalist industrialism” (p. 101). A key concern of much of this work is mapping who owns the media, systems of control and regulation and structural changes in the ways that information is produced and processed. iv Pseudonyms of those who posted are stated in parentheses after each post.