“The Ruling Class and Elites” section in the Social Stratification

advertisement

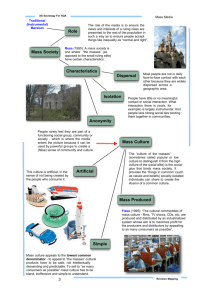

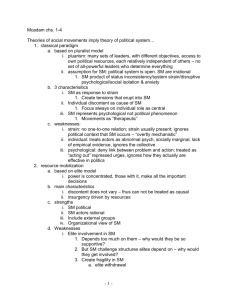

“The Ruling Class and Elites” section in the Social Stratification reader (ed. Grusky) Sections Include: CLASSIC STATEMENTS: Mosca, Gaetano. “The Ruling Class.” Mills, C. Wright. “The Power Elite.” Giddens, Anthony. “Elites and Power.” CONTEMPORARY ELITES IN “MASS SOCIETY,” CAPITALISM, AND POSTCAPITALISM: Shils, Edward A. “The Political Class in the Age of Mass Society: Collectivistic Liberalism and Social Democracy.” Useem, Michael. “The Inner Circle.” Eyal, Gil, Ivan Szelenyi, and Eleanor Townsley. “Post-Communist Managerialism.” Summary by Brian Asner ABSTRACT This section is concerned with the question: Is there a class or group of people who monopolize the power to rule a society? Each account is responding to (either directly or indirectly) Gaetano Mosca’s piece, with Eyal et al. responding also to Mills, and Useem responding directly to Mills. See diagram (arrows indicate “responding to”): Mosca (1939) Mills (1956) Giddens (1973) Useem (1984) Shils (1982) Eyal, et al. (1998) The debates among the “classic” elite authors go something like this… Mosca argues that in all societies, a minority ruling class inevitably emerges to rule the majority. This class takes different forms as societies develop: warrior classes rule primitive societies by force and use this force to usurp land (wealth), but this wealth is later converted into political power in the modern bureaucratic state. Mills responds that power does not come a specific class of families and resources, but rather the occupation of particular positions in the social structure. Mills believes that the growth of three major institutions (the economy, the government, and the military) has led to increasing overlap between the leaders of each realm. These leaders comprise the core of American power, and are the only individuals with true influence in society. In response to Mosca, Marxists, and basically any elite theorist, Giddens offers a nuanced typology full of details that we most certainly don’t need to know. However, he does make an important contribution by suggesting that numerous elite groups can coexist within a single society (as opposed to just one elite), with each exhibiting different levels of influence, recruitment, and integration. Grusky Reader: “The Ruling Class and Elites” Section 1 And now… put your hands together for… the contemporary elite theorists! Shils claims that Mosca’s theory is no longer applicable in a modern society dominated by popular democracy, since political elites are accountable to public opinion. As a result, they are unable to simply impose unpopular measures on the public. Useem argues that an “inner circle” of business elites has emerged in the past half-century, composed of individuals who are more concerned with the welfare of their class (composed of large corporations) than attracting wealth to their families or own businesses. Eyal, Szelenyi, and Townsley imply that classical elite theories are describing one particular type of capitalist development, and suggest that postcommunist capitalism creates a fundamentally different set of elites. Rather than rewarding a landed bourgeoisie or political lineage, post-communist capitalism has been most beneficial for former socialist managers, especially financial managers. SUMMARY OUTLINE Mosca (1939): Mosca argued that in all societies, it is inevitable that a minority ruling class emerges to rule over the majority. Although the masses may exert pressures that influence the ruling class, and also supply the material subsistence which is necessary for its operations, the ruling class is nonetheless structured to implement and enforce the orders of a dominant leader. The ruling class is necessarily a minority (because only a small group can govern effectively and in unison), and the ruling class members “regularly have some attribute, real or apparent, which is highly esteemed and very influential in the society in which they live” (197). The historical development of the ruling class begins with the rise of a warrior/military ruling class in primitive societies. This class is seen as racially superior, which is often the result of foreign invasion (for example, the Spanish invasion of the Aztecs). However, as societies develop from nomadic hunters to pastoral (settled) agriculturalists, the society divides into distinct classes (agriculturalist and warriors), with the warriors also acquiring a “racially” superior status. The military class acquires land, which is converted to wealth as society develops. In other words, (political) power produces wealth. This evolution ultimately creates a “bureaucratic state” where the protection offered by the “public authority” (i.e. the state) is more substantial than the private force of warrior groups (198). At this point, wealth and power reciprocally reproduce each other. This societal evolution is paralleled by a shift from religious authority to science-based authority, although the latter is the result of knowing how to apply this knowledge in a practical sense rather than simply being knowledgeable. In other words, a ruling class will develop a “real art of governing” that enables their “political lineage” to remain in power (199, 217). Thus, Mosca argues, “all ruling classes tend to become hereditary in fact if not in law” (199). Even though degrees and trainingi, or democratic elections, are implemented to counteract this hereditary concentration of power, the offspring of the ruling class have distinct resource advantages that enable them to achieve these credentials or win elections (as well as the knowledge of how to govern effectively). Mosca’s final observation comes from the application of evolutionary principles. If the ruling class passes on the capacity to rule to their children, the ruling class ought to become increasingly proficient at maintaining their dominance over societies. Yet, this is not the case. Mosca resolves this dilemma by claiming that a shift in the “balance of political forces” can Grusky Reader: “The Ruling Class and Elites” Section 2 devalue the qualities on which the ruling class’s authority is founded, thus destabilizing the ruling class and ultimately leading to its replacementii. Mills (1956): In response to Mosca, Mills claims that it is not the passing on of resources by specific families, but rather the occupation of power positions in the social structure which determines who rules a society. Mills claims that Mosca makes a tautological argument in claiming that all major historical events are shaped by a ruling class. Instead, Mills identifies a power elite with centralized decision-making powers, and claims that the increasingly concentrated elite power leads to decisions with more significant social ramifications. In opposition to pluralist theories of power, Mills claims that ordinary citizens have little effect on their surrounding societies. Instead, a small group of extremely powerful individuals comprise the power elite: “…those political, economic, and military circles which as an intricate set of overlapping cliques share decisions having at least national consequences” (209). Noting a decreasing influence of religion, education, and family, Mills argues that modern society is dominated by three major institutions: the economic realm, the political realm, and the military realm. As each realm has grown enormously in size and technical proficiency, these entities have become highly centralized, extremely powerful institutions at the “command posts of modern society” (203). Furthermore, the entities have also become increasingly intertwined, with the overlapping elites of each group forming the power elite. However, simple acquisition of wealth is not sufficient to become part of this power elite; neither are individual characteristics of powerful people. Instead, it is the occupation of specific positions within the “big three” entities that provides the necessary resources (power, wealth, and prestige) and the means for effectively applying these resources. Mills argues that power gradations exist within particular institutions, but there is a clean break regarding the power elite: you are either in or out. The power elite is a “self-conscious… social class… of overlapping ‘crowds’ and intricately connected ‘cliques’” (205). However, the American elite is unique in that its members assume that no such elite exists, and often deny that they are powerful. Furthermore, the American elite is historically unique because it did not arise in opposition to an entrenched feudal nobilityiii; instead, it was “a virtually unopposed bourgeoisie… [with a preexisting] framework of power and an ideology for its justification” (206). Mills does agree with Mosca that the power elite tends to be viewed as people of “superior character” compared to the mediocre masses (207). However, Mills believes that the power elite actually has the resources to cultivate some of these superior characteristics. Giddens (1973): Whereas Mosca and Mills are theorizing about a particular elite class which dominates a given society, Giddens argues that different types of elite groups may coexist, and must therefore be distinguished analytically. Giddens suggests that some of the irresolvable conflicts between Marxian theorists and elite-theorists stems from confusing and conflated terminology, as well as an unclear description of the different ways in which economic dominance is translated into political dominance. Giddens proposes a distinction between the concepts of “ruling class,” “governing class,” “power elite,” and “leadership group,” arguing that each type of elite group may emerge in capitalist societies, but may or may not overlap. Grusky Reader: “The Ruling Class and Elites” Section 3 Giddens defines “elites” as “individuals who occupy positions of formal authority at the head of a social organisation or institution” (213), and is concerned with a few components of elite structuration. First, he examines the recruitment and potential for mobility into an elite group; in other words, is the group “closed” to individuals from non-elite backgrounds? Also, Giddens considers the degree of solidarity within elite groups, primarily based on the frequency and nature of interactions between group members. In addition to these two characteristics of elite groups, he also makes two distinctions regarding the “institutional mediation of power”– in other words, the way in which an elite group implements its power in the political and economic environment. The “collective” side concerns whether the power in the society is consolidated among the elites, or if power is relatively diffused throughout society. The “distributive” side refers to the range of issues which the elite group may dominate (either a broad range or restricted range). After devising a number of other terms to further confuse us, Giddens creates the following typology (from page 215, although I’ve removed the unnecessarily confusing titles for each group type). Elite Formation Ruling Class Closed, with varying degrees of integration Governing Class Closed, with varying degrees of integration Power Elite Open for mobility, highly integrated Leadership Groups Closed, highly integrated Power-Holding Power is consolidated in society, but elite influence may be very strong (broadly distributed) or relatively weak (limited distribution) Power is diffused in society, but elite influence may be very strong (broadly distributed) or relatively weak (limited distribution) Power is consolidated in society, but elite influence may be very strong (broadly distributed) or relatively weak (limited distribution) Power is diffused in society, but elite influence may be very strong (broadly distributed) or relatively weak (limited distribution) Giddens acknowledges that this incredibly helpful, crystal-clear table does have one shortcoming: the system does not address how elite groups have different levels of power relative to each other, which forms a social hierarchy of elite groups. Shils (1982): Shils claims that society has changed significantly since the time of Mosca’s observations. Although Shils does not explicitly applaud or condemn Mosca’s theory, he feels that the “collectivistic liberalism” and “mass society” of the modern era differ significantly from Mosca’s surroundingsiv. Shils claims that modern societies require “a tremendous concentration of power in the government” (218) in order to obtain and distribute resources to a population with extremely high, varied, and rapidly changing demands. The inherited “art of governing” described by Mosca is no longer sufficient for the enormous complexity of governance. Instead, each branch of government has developed an enormous bureaucracy in order to govern. Shils also argues that the tenets of modern liberalism, including the “emphasis on individual achievement” (220) and technological advancement, has undermined the generational dominance of landowning elite families. In addition, the religious institutions which helped maintain the power of the elite families have shifted their support (both by choice and by the enforced separation of church and state). Furthermore, the American (and German) educational systems do not contribute to the same level of class reproduction as in some countries (such as Grusky Reader: “The Ruling Class and Elites” Section 4 the UK and France). Finally, the local and state political machines are far more united and powerful than at the national level, which further inhibits the emergence of a unified ruling class. So where are we going with all this? Shils believes that Mosca’s theory is no longer applicable to modern society because today’s politicians are held accountable to popular demands, opinions, and critical scrutiny. Therefore, the rulers cannot simply impose their will on the population. From Shils’ perspective, the characteristics of modern popular democracy inhibit the emergence of a “closed” class of ruling elites. Instead, modern political elites must constantly consider whether their rulings are considered acceptable by the citizenry. Useem (1982): Useem claims that theorists have been sharply divided about whether the upper class exists, is unified, and is conscious of itself. Useem argues that neither answer is appropriate, and instead proposes that a politicized segment of the business leadership has taken a leading role in defining and promoting the needs of a broad community of large corporations. These individuals are concerned more with the welfare of the business community than their individual businesses (even if they will benefit minimally from a successful business community). Useem argues that the inner circle has emerged out of two parallel developments: the evolving organization of the business community, and the development of the organization of elites. First, he describes the transformation from “family capitalism” (such as the system described by Mosca) to “managerial capitalism” (such as Weberian bureaucracy) in the 1900s (226). Since World War II, however, Useem sees a transition from managerial capitalism to “institutional capitalism,” in which both family and corporate interests have given way to the prioritization of “the shared interest and needs of all large corporations taken together” (226). This movement is paralleled by development of social organization from an upper-class principle, to a corporate principle, and settling in the modern day class-wide principle. Useem claims that the inner circle is not a unified whole (like a Marxian class), but instead a range within which only the most powerful, well-connected, and resourceful actors are situated. The inner circle also includes the network structure between these actors. Eyal, Szelenyi, and Townsley (1998): Although these authors don’t claim to be responding to Mosca or Mills, it seems that Grusky has included this article to suggest that Mosca and Mills are describing a particular condition of a specific form of capitalist developmentv (rather than a universal rule of human societies). The article by Eyal et al. examines the rise of post-communist capitalism in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland. The authors focus on this area because of its historical uniqueness; namely, the infusion of capitalism into a region without a propertied bourgeoisievi. The authors suggest that in most instances, capitalism has grown out of feudalism, with the feudal landlords converting their land into private property and forming a new capitalist elite. Since the Central European nations lacked private property under state socialism, these classical elite explanations are obviously inappropriate. Leading Central European scholars have offered theories which resemble classic elite theorists, suggesting that the communist nomenklatura began planning to convert their political offices to private wealth once they realized the inevitable demise of communism (a theory labeled “political capitalism”). The data from Eyal et al. are not consistent with the political capitalism theory, showing instead a massive downward mobility of more than half of the communist nomenklatura in the five years following the transition to capitalism. In fact, when Grusky Reader: “The Ruling Class and Elites” Section 5 the authors divide the nomenklatura into the political elites, cultural elites (i.e. academics, newspaper editors), and economic elites, they found that the political elites fared worst during the transition. Instead, the economic elites have been most successful at maintaining their resources and social status. However, different segments of the economic elite did not all fare equally well. While some theorists predicted that “managerial owners” would be the major beneficiaries of the former economic elite, the authors show that ownership of Central European corporations is a unique hybrid that is neither public nor private (237). Therefore, the benefits of ownership are limited and convoluted. Instead, the authors claim that high-level managers, especially those who are part of the “technocracy,” have benefited most during the transition to capitalism. Based on these results, the authors offer a theory of managerial capitalism. In brief, the theory suggests that the elimination of state-controlled redistribution has led to post-communist economies being characterized by diffuse property relations. Since a propertied bourgeoisie does not dominate the post-communist societies, the emerging power bloc is simply composed of those who are visibly exerting managerial control and decision-making. Finance managers have been most successful in exerting this managerial power, since their knowledge of capitalism is essentially a form of “cultural capital” that all citizens are trying to achieve (237). Yet, this emerging, and incomplete, class recognizes the precariousness of their power position, as opposed to the steady confidence of classical elite groups. RELEVANCE / CONNECTIONS At some point in the development of an elite theory, an author will inevitably encounter Marxist descriptions of class, so that might be useful to keep in mind. Otherwise, see my purty little chart in the Abstract to see which authors are talking to each other. This is Weber’s “credentialism” discussion; see the summary for Weber’s section in the Grusky book. This suggests that Mosca accurately foresaw the retorts of authors such as Shils and Eyal et al. (included in this summary). Both of the latter authors describe fundamentally different political conditions from those observed by Mosca, and thus find different explanations for the dominance of a particular ruling class. iii Note that Eyal et al. claim that the Central European situation is “unique” for precisely the same reason. iv As mentioned in the Mosca section, Mosca predicted this limitation at the end of his piece. v Again, Mosca covered his ass on this point. vi Note that Mills claims that the American situation is “unique” for precisely the same reason. i ii Grusky Reader: “The Ruling Class and Elites” Section 6