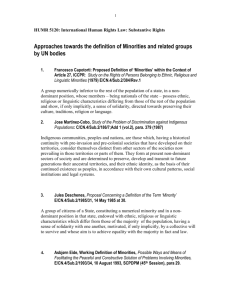

Introduction - School of Media and Communication

advertisement