For-Profit, for Students

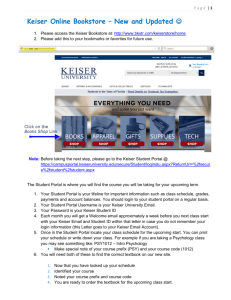

advertisement

From the issue dated June 28, 2002 For-Profit, for Students Keiser Colleges offers courses designed to lead to better jobs By ANNE MARIE BORREGO Pembroke Pines, Fla. Arthur E. Keiser knows that students don't come to his colleges for the love of learning or the modern ALSO SEE: facilities. The Keiser Collegiate System Arthur E. Keiser "They're here because they have a pain in their life, a concern that they can't deal with on their own," Mr. Keiser said to a small group of admissions officers at the newest Keiser Career Institute campus in this stripmalled suburb between Fort Lauderdale and Miami. "They don't want their kids to grow up like they did." Quite simply, his students need better jobs. And Mr. Keiser tries to ensure that the 11 institutions in the system give students what they are looking for. Because the colleges aim not just to educate but also to prepare students for jobs, they have a strict professional dress code -- ties for men, professional slacks, skirts, or dresses for women in nonmedical courses. And because Mr. Keiser knows that the stakes are high for his students, Keiser's colleges hold their instructors accountable, requiring them to turn in a daily lesson plan for administrators' review. The Keiser system has flourished thanks to this approach. The family business that started in 1977 in a small storefront in Fort Lauderdale now comprises seven Keiser College campuses, three Keiser Career Institute locations, and Everglades College. All told, they took in about $53-million in revenue last year. Keiser is neither a mammoth publicly traded highereducation company nor one of the hundreds of singlecampus mom-and-pop proprietary schools that serve an extremely narrow niche. Rather, it is among a small group of medium-sized chains that are limiting their growth in certain ways -- in Keiser's case, by choosing to stay within Florida -- but aggressively pushing the boundaries of for-profit higher education in others. Keiser has done that by winning regional accreditation from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, by preparing to offer bachelor's degrees in the fall, and by becoming the first proprietary institution in Florida to offer an associate degree in nursing. A Modular System Mr. Keiser's mother, Evelyn C. Keiser, still strolls in each day at 5:45 a.m. to her first-floor office at the company's headquarters in Fort Lauderdale. Listening to Beethoven streaming over the Internet, she can well remember the first student who came to the allied health college she had opened with her son. Space was so limited that the owners stored exam papers and slides for the overhead projectors in their cars. While the Keisers have moved up -- their corporate headquarters occupies a six-floor building -- they have clung to many of the core policies they developed then. Because most of his students have other responsibilities and come from lower-income environments, Mr. Keiser contends that they don't learn the same way that traditional college students do. So, the Keisers created a modular system for their students, which entails taking one monthlong, three-to-four-credit class at a time. Depending on the degree, students spend from 12 to 25 hours in class each week. "They don't have the ability to study four courses at a time that are unrelated," Mr. Keiser says. This way, they are immersed in smaller classes -- the average class has about 15 students -- and the optional tutoring after class. They also like the dress code. "It gets the students prepared and sets the tone," says Debbie T. Peart, a 20-year-old studying radiological technology. Like all students in the medical- or dentalassisting programs, she wears scrubs to class. Different programs wear different colors; hers are aqua. For their money, Mr. Keiser says he tries to give his students an education that will make them employable when they graduate, which both Keiser's peers and competitors say he does well. "As far as I can tell from talking to the dean of our undergraduate school, Keiser certainly does provide a solid education for its students," says Ray Ferrero Jr., president of Nova Southeastern University, in Fort Lauderdale, which since 1998 has had an agreement that allows Keiser students to transfer there. A Bell Curve for Instructors Keiser provides that kind of quality, in part, by expecting a lot of its instructors. Gery Hochanadel, Keiser's vice president for academic affairs, says the institution takes its time when hiring new faculty members, making sure that they are not just good instructors. "They need to take ownership of students who don't come to class," he says. "They need to want to call that student at night and go over whatever he or she missed." In addition to formal interviews, prospective instructors must prepare classroom presentations. They must also create daily lesson plans from a standardized syllabus that Keiser develops in-house. About 30 days before a class starts, all faculty members turn in their lesson plans, which must be approved by Mr. Hochanadel, individual deans, and campus directors before instructors begin their next class. "Instructors from the traditional sector aren't as excited about the process," Mr. Hochanadel says. Neither were longtime faculty members who were introduced to the detailed lesson planning about three years ago. Newer faculty members, on the other hand, especially those not as accustomed to teaching, "love it," Mr. Hochanadel adds. "They're my lesson plans," says How S. Shows, a veteran of community colleges and four-year institutions who teaches a survey course on American literature that often includes Hawthorne, Melville, and Poe. "It's not like there's some master plan that I'm making the lesson plans from." At the end of each modular period, every instructor is evaluated, based on students' pre- and post-course test scores. Mr. Hochanadel also factors in student surveys, attendance records, and dean evaluations, and places the resulting number on a bell curve. "Then we look at our outliers," he says. Those who rise above the curve are rewarded -- the top five instructors in each area of study are treated to workshops, which the administration uses to identify its high performers and their techniques. And those who fall at the bottom of the curve, Mr. Hochanadel says, have to improve, and if they don't, they are dismissed. Mr. Keiser expects his classes to be difficult and wants to ratchet up the demands made on his students, though he doesn't want them to fail. After-class tutoring is encouraged, though Mr. Keiser says his institutions will not admit students who cannot pass the admissions exam. Controlled Growth Unlike his larger, publicly traded brethren, Mr. Keiser has focused on trying to keep expansion at a reasonable pace, growing at between 12 to 14 percent annually, to avoid a loss of quality control. When the company posts a profit, Mr. Keiser puts 40 percent back into the institutions. Mr. Keiser, however, can't keep all things under control. At a weekly meeting of vice presidents here late last month, he complained about excess spending. "Every time we waste money, they pay for it," he said, referring to students. While he was pleased that 19 unused computers were being shipped from Keiser's Sarasota campus to another one, he was clearly perturbed that they were sitting idle in the first place. "We'll be dead if we can't get waste under control," he said. "We had 76 computers in inventory, and we're going out and buying new ones?" Cost is a competitive issue. Keiser's $10,000-a-year tuition is more than twice that of nearby Broward Community College. "It's a cheap state to go to school," Mr. Keiser says. Analyzing costs has led Keiser to drop some of its underperforming programs, like maritime hospitality to train cruise ship staff, which never really took off, and travel services, which took a significant hit with the advent of Internet travel sites. Keiser competes in a hot for-profit market. Between its Florida Metropolitan Universities and National Schools of Technology, Corinthian Colleges Inc. boasts 12 campuses in the state. The Apollo Group's University of Phoenix has four campuses in Florida, and DeVry University is opening up shop just one exit away from Mr. Kei-ser's new Pembroke Pines location in South Florida. The state has the fourth-highest proportion of students attending for-profit institutions, with some 28,175 students, or about 4.3 percent, enrolled in proprietary institutions in 1998, according to the Education Commission of the States. Mr. Keiser relishes the competition and looks to other institutions for ideas, noting that he is excited about DeVry's opening. "When we started our computer program, they were my model." He follows a "their success is my success" motto, investing approximately $5,000 of company money into each for-profit higher-education company when it goes public. That strategy has paid off: The "school index" of the shares he still holds has increased by 331 percent. Individual vice presidents at Keiser each monitor a publicly traded competitor, reporting on significant news and new strategies. Political Ties Mr. Keiser and his wife, Belinda M. Keiser, are such cheerleaders for the for-profit sector that they regularly take their message to the halls of Congress and the Florida statehouse. They and Mr. Keiser's mother have collectively given more than $70,000 to lawmakers in both houses of Congress and the Florida Legislature, and to the Democratic National Committee, since 1999. Mr. Keiser helped found the Career College Association's political-action committee, and believes that career colleges must work hard to introduce themselves to policy makers, because most of them attended traditional nonprofit institutions. "In some minds we're stereotyped into something we're not," he says. Mr. Keiser understands that the relationship between government and the private sector is "a partnership," says Bruce D. Leftwich, the Career College Association's vice president for government relations. "When he goes to lobby, he believes, as a lot of us believe, that you can't always go asking something. You have to be able to say, 'I'm a resource to you,'" he says. "And he invests a lot of capital to do that." The Keisers' donations seem to have paid off. In 1998, Belinda Keiser led the charge to admit for-profit institutions into Florida's common course-numbering system. The system, which was established in 1971, created state-assigned numbers to general college courses, to try to ease the process of transferring credits. Comparable classes were assigned the same number, so students could transfer from community colleges to private colleges or public universities in the state without having to retake similar courses. Not being included in the system was "a real frustration for me," says Ms. Keiser, whose foray into politics led to a recent run for state representative, which was unsuccessful. "We were SACS-accredited and our students would go to Florida State and get bogged down in the transfer-of-credit process," she says. Keiser students' credits are now recognized. Not every political fight has paid off, though. This year, Keiser College, South College, and International Fine Arts College, all regionally accredited, Florida-chartered for-profit institutions, pushed for access to Florida's Resident Access Grant, which provides up to $2,800 a year to Florida residents who attend in-state private colleges. Only those students attending colleges with state charters, regional accreditation, and nonprofit status can tap into the funds. Mr. Keiser believes the tax-status stipulation is unfair, since all institutions receiving the funds would have to pass muster with a regional accreditor. "Why should we be discriminated against because we pay taxes?" he asks. Florida's private colleges fought back. Nova Southeastern's Mr. Ferrero says the grant was meant to go to students who attend colleges and universities that are most like those in the state system -- Floridachartered, nonprofit, degree-granting, and regionally accredited. Mr. Ferrero says he would not take a position on whether Keiser and other for-profits should seek a grant program of their own. "If they can convince the Legislature that that's important for their students ... would I oppose it? No. I wouldn't oppose it," he says. State legislators eventually crafted a new bill that would create such a grant program, which passed in the House but failed in the Senate. Ms. Keiser says their push for access to state money is really about their students, not padding their coffers. "The degrees our students pursue are in the highdemand work-force areas that Florida needs," she says. "This would be a good investment in Florida." THE KEISER COLLEGIATE SYSTEM Founded: 1977 by Arthur E. Keiser and his mother, Evelyn C. Keiser Institutions operated: Keiser College, Keiser Career Institute, Everglades College Locations (all in Florida) Keiser College Daytona Beach Fort Lauderdale Lakeland Melbourne Miami Sarasota Tallahassee Keiser Career Institute Lake Worth Pembroke Pines Port Saint Lucie Everglades College Fort Lauderdale Programs Keiser College offers associate degrees in business, computer technology, and allied health. Everglades College offers bachelor's degrees in business administration, information technology, e-commerce, aviation management, and professional aviation. Accreditation Keiser College is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. Keiser Career Institute and Everglades College are accredited by the Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges of Technology. Total students: 4,300 Faculty: 288 instructors, 64 percent of them full time; 17 percent have Ph.D.'s Tuition: $5,000 for the equivalent of one semester 2001 revenue: $53million SOURCE: Chronicle reporting Copyright © 2002 by The Chronicle of Higher Education