- Electronic Journal of Comparative Law

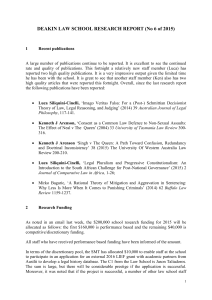

advertisement