(2007) Study Guide

advertisement

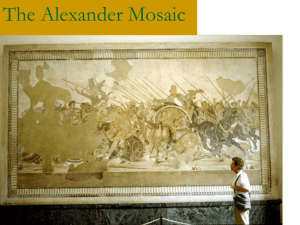

Achaemenian Persian Empire – founded by Cyrus, the Achaemenian Persian Empire lasted from 559-330BC. The Achaemenian Persians were the Greeks’ continual archenemy, and only with the triumph of Alexander were they conquered. Achilles – hero of the Iliad and son of Thetis and Peleus and ancestor of Alexander. Had a homosexual relationship with Patroklos that closely paralleled that of Alexander and Hephaisteion. Alexander strove to outdo Achilles in battle and in lands conquered. Aigai (also, Aegae) = Vergina (modern name), the ancestral royal capital of Macedonia. Despite the movement of the capital to Pella under Philip’s reign, Aigai retained immense religious and ceremonial importance in Alexander’s time. Anthropomorphic – relating to the attribution of human characteristics or behavior to a god, animal, or object (OED). In Greek culture, this included assigning emotions to the gods, who constantly required sacrifice, e.g. Alexander’s innumerable sacrificed animals, to remain pleased or to bestow favors. Apelles – renowned painter, employed by Philip II and Alexander. Portrayed Alexander and Philip II together, and Alexander famously alone in Alexander Wielding a Thunderbolt (no longer extant). Aristotle – most famed student of Aristotle and a teacher of Alexander the Great, by Philip II’s invitation (Aristotle was not so famous at the time). Instructed Alexander in philosophy; it is unknown whether Alexander truly enjoyed the subject or simply appeared to for propaganda. Arrian – a Greek historian of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Focused extensively on military history and Alexander the Great. One of the most coherent sources we have on Alexander, and one from which Romm draws heavily in Alexander the Great. Athena – clever warrior goddess and patron of Troy. Alexander sacrificed to Athena at Troy in the hopes of not incurring the bad luck of his forerunners after the Trojan War. Attribute – an object that identifies a particular figure, hero, or god. Hercules and Alexander had an anastole (“lion coiffure”) attribute. Herodotus- (484BC to 425 BC). Known as the father of history due to his chronicles of Persia and its invasion of Greece in the early fifth century BC. He talks of the growth of the Persian Empire and then the defeat of the Persians at Marathon. He ends with the Battle of Plataea, in which Xerxes is utterly defeated. Used as a reference by Alexander for his journeys through the known world and his accounts of Persia. Heroic Nudity- term used by scholars to describe the significance of nudity in Greek art. Refers to nudity as a costume, which implies a sense of heroism, divinity Homer- legendary early Greek poet who wrote the Iliad and the Odyssey. Wrote the history which enthralled and captivated Alexander…namely that of Achilles, whose behavior Alexander emulated. Hoplite- a heavy infantryman that was the central focus of warfare in Ancient Greece. These soldiers probably first appeared in the late seventh century BC. They were a citizenmilitia, and so were armed as spearmen. They were primarily drawn from the middle class, who could afford the cost of the armaments. Almost all the famous men of ancient Greece, even philosophers and playwrights, fought as hoplites at some point in their lives. Hubris-- exaggerated pride or self-confidence often resulting in retribution. Common theme in Greek tragedies and mythology, whose protagonists suffered from Hubris and were punished by the gods. Idealism-The idealizing of the human form to make mortals appear G-d-like and heroic. Used mostly in the Classical period and less in the Hellenistic period. Iliad- together with the Odyssey, is one of two ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. Most modern scholars consider the epics to be the oldest literature in the Greek language , dated to the 8th or 7th century BC. The poem concerns events during the tenth and final year in the siege of Troy. Alexander attempted to emulate the poem’s main character, Achilles. Larnax- a type of coffin used in Ancient Greece to store human ashes. Two larnax’ are found in Tomb II, which some scholars believe to be the tomb of King Phillip II. The large larnax is believed to hold the King’s remains, and the small one holds the remains of one of his wives. Lysippos- born c. 390 BC, was Alexander’s personal sculptor during his lifetime. He is credited with the stock representation of an inspired, godlike Alexander with tousled hair, lips parted, looking upward Manolis Andronikos- Archaeologist, excavator of the Great Mound, believed to be the tomb of King Phillip II at Vergina. Significant because the tomb was found unopened and in its original context and sheds light on Ancient Greek burial rituals. Memphis- Had been the most prestigious city in the Persian empire but fell into second place following the foundation of Alexandria. Under the Roman Empire, Alexandria remained the most important city. Memphis remained the second city of Egypt until the establishment of Fustat (or Fostat) in 641. Provenience (Provenance): the source and ownership history of a work of art or literature, or of an archaeological find. It is important to know where an artifact comes from for two main reasons. First, knowing when and where an artifact was made allows to determine whether it is genuine or a phony. Second, and more importantly, determining an artifact’s provenance allows us to speculate about its historical/cultural significance. For example, because we know that the Large Larmax from Tomb II at Aiguae was excavated during the nineteenth century from a tomb that had not been previously tampered with, we can speculate that it was placed there in honor of Philip II, as other evidence discovered there indicates it was his tomb. Sarissa This is a very long spear that was introduced by Philip II. His army lined up in tight phalanxes and successfully used the sarissa to easily penetrate the lines of enemy warriors who used shorter weapons. Philip’s son, Alexander the Great, adopted this weapon and this type of warfare with unprecedented, and never again matched, success during his own legendary conquests. To support the phalanxes, both Philip and Alexander used cavalry and light infantry. Satrap/ Satrapies This was the title of governors of the ancient Persian Empire. When Alexander the Great conquered their territory, he would variously install his own satraps or, if the existing satrap yielded without fight, he would simply appoint a Macedonian to make sure the satrap paid tribute. “Siwa Oasis” This oasis is located in Egypt and it was the location of the oracle of Zeus Amnon, a composite of Zeus and a Ram. Alexander the Great consulted this oracle on several occasions, and from it he was supposedly told he cannot fail. The significance of this is that Alexander frequently respected the deities of foreign places in order to enhance his own prestige. This is captured by the fact that Zeus Amnon is sometimes personified as a ram and that Alexander the Great had images made of him self with ram horns, indicating that Alexander wanted to portray himself as a descendent of this deity. “Spear Won” or “won by the spear” is a Homeric saying that Alexander the Great supposedly arrived when he arrived in Asia after he put his spear in the earth. This demonstrates that Alexander the Great was profoundly influenced and inspired by the Homer. Indeed, Alexander is reputed to have owned a copy of Iliad as a gift from Aristotle which he carried everywhere. Like the Homeric heroes, Alexander saw himself as a descendent of the gods, specifically Zeus and in images he sometimes takes on attributes of Zeus, including the lion mane hairdo or the thunderbolt. Susa This is the great Persian city where tribute used to be brought. This was a wealthy city and full of gold. However, when Alexander the Great conquered it, he destroyed it, possibly as revenge for when Persia destroyed Athens. Excavations of Susa have yielded luxurious artifacts. (I’m not entirely certain of course-significance, however.) Syncretism This is the notion of equivalent deities. Alexander the Great, like many ancient Greeks, was a proponent of syncretism, as he accepted many foreign gods into the pantheon. For example, he respectfully visited the oracle of Zeus Amnon, a god in Egypt, and he treated him as Zeus. He even took on in his own images the ram horns associated with this god, in order to indicate he was a descendent of this deity. Trojan War In Iliad, Homer describes this war between the Trojans and the Greeks in which gods, demigods, and mortals all fought. This epic defined heroic Greek virtues which Alexander the Great emulated. Like Achilles, Alexander saw himself as a descendent of Zeus, and Alexander had himself portrayed with attributes of Zeus, for example, the lion hairdo and the thunderbolt. Further, on the battlefield, Alexander frequently fought with the reckless abandon of an immortal as he might have believed himself to actually be immortal. In images of Alexander, for example, the ____ Alexander is depicted as brave and fearlessly leading his men. Statue of King Khafra Artist: n/a Date: c. 2558-2532 BCE Culture: Egyptian Material/Format: Diorite Note the royal god Horus in form of a falcon behind the king's head. The relief on the side of the throne symbolizes the union of Lower and Upper Egypt. It features two symbolic plants: the papyrus of Lower Epypt, and the "lily" of Upper Egypt. The man being portrayed, King Khafra, ruled Egypt for approximately thirty years, during which he commissioned the single most recognizable monuments of Egypt, the Pyramids at Giza and the Sphinx. These monuments of symmetry and solidity characterize the focus of popular architecture and sculpture from the Old Kingdom in Egypt. Khafra wears the nemes headdress, surmounted by the uraeus, or royal cobra. He wears the royal pleated kilt. Attached to his chin is an artificial ceremonial sacred beard. He is protected by the god Horus, represented as a falcon, perched at the back of his neck. This artifact is a masterpiece of workmanship. The sculptor was able to depict the details of the facial features and muscles of the body, in spite of the hardness of the stone. Static works like this contrast with the more active specimens we retrieve from the Greeks. King Menkaure and Queen Artist: n/a Date: c. 2490-2472 BCE Culture: Egyptian Material/Format: Schist Youthful vigor characterizes the figure of the king as he strides forward, protectively embraced by the queen. His head is turned slightly to the right, while the queen's face is fully frontal, as if she were presenting him to the world and endowing him with confidence and strength. While scholars may have gone too far in suggesting that this dominating female is a goddess, it is possible that we see not the king's consort but his mother. Such an image would have served as a potent guarantee of Menkaure's rebirth after death. The group was not finished, since the lower part has not been fully smoothed. Paint was applied, as seen in the traces of red on the king's ears, and sheet gold may once have covered the woman's wig and the king's headdress. The coverings would have incorporated a cobra above the king's forehead and, possibly, a vulture headdress above the queen's wig. For the first time in Egyptian art, both royal heads are not images of idealized royalty but portraits of specific holders of the offices. The king's bulbous eyes, hanging flesh on the cheeks, and drooping lower lip are unmistakably features of an individual, as are the queen's long full neck and small mouth. While the king's body is ideally youthful and athletic, one might see hints of maturity in the woman's breasts. From: http://www.metmuseum.org/explore/new_pyramid/PYRAMIDS/HTML/el_pyramid_menkaure.htm Stele with Law Code of Hamurabi Artist: n/a Date: c. 1800 BCE Culture: Old Babylonian Material/Format: Basalt relief The Hammurabi stele image is done in bas-relief on basalt, and the text completely covered the bottom portion of the stele with the laws, written in cuneiform script. The text contains a list of crimes and their various punishments, as well as settlements for common disputes and guidelines for citizens' conduct. The The stele was openly displayed for all to see (public art); thus, no man could plead ignorance of the law as an excuse. Scholars, however, presume that few people could read in that era, as literacy was primarily the domain of scribes. Detail of Stele with Law Code of Hammurabi, Hammurabi and Deity Artist: n/a Date: c. 883-859 BCE Culture: Neo-Assyrian Material/Format: Limestone relief Hammurabi’s law code was discovered in 1901 when achaologists were digging through Susa. At the top of the stele we see a picture of the bearded god Shamash, seated on his throne. The god holds a scepter, a symbol of power. Facing the god is Hammurab who holds one hand to his lips as he receives legal enlightenment from his god, with the message that with the stele, Hammurabi dispenses the will of the gods. Ashurbanipal Hunting a Lion Relief of King Ashurnasirpal II Artist: n/a Date: c. 668-627 BCE Culture: Neo-Assyrian Material/Format: Limestone relief Rock relief at Bisitun of Darius I Artist: n/a Date: c. 510 BCE Culture: Achaemenid (Persian) Material/Format: Limestone rock relief Regard the winged genius, a symbol of Persian greatness. Look also at the size of the Persians (left) relative to the prisoners (right). The arrangement of the Persians’ hair also appears significant, perhaps indicating their superior civilization relative to that of the captives. (Lecture 4) Rock relief at Bisitun. Detail of Darius I Artist: n/a Date: c. 510 BCE Culture: Achaemenid (Persian) Material/Format: Limestone rock relief Note Darius I’s large size relative to that of his attendants, and more markedly, relative to that of the prisoners. Darius is trodding upon (probably) another King. His stature and beard are part of the Achaemenid canon. (Lecture 4) Audience with Darius I Artist: n/a Date: c. 510-485 BCE Culture: Achaemenid (Persian) Material/Format: Limestone relief Again, Darius is portrayed as enormous, as large as the largest standing figure while sitting. Height clearly conveys a hierarchy in this figure. The supplicant is also slightly bowed, further emphasizing the role of height as a sign of status. The ornate throne, dual midsized pillars, and many attendants indicate the ruler’s power and wealth. (Lecture 4) Achilles Bandaging Patrokles' Wound Artist: Sosias Date: c. 500 BCE Culture: Greek Material/Format: Painted ceramic, drinking cup Achilles and Patroklos, whom Alexander sees as mirrors of him and Hephaisteion. Note the intensity of Achilles’ eyes, perhaps depicting homoeroticism. (Lecture 4) Anavysos Kouros Artist: n/a Date: c. 530 BCE Culture: Greek Material/Format: Marble Nude and freestanding. An exemplar of Yuhan’s saying “in many ways, nudity is a costume”. Nudity not in correspondence with sexuality, here. Archaic smile. (Section 1) Kritios Boy Artist: Kritios Date: c. 480 BCE Culture: Greek Material/Format: Marble QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. Alexander Mosaic- Gazing at a slight angle. Slightly turned shoulder, seems more active. More dynamic back (Kouros may not have had a back). Note the difference in musculature between this sculpture and the sculpture above. (Section 1) Artist: Original painting by Philoxenos of Eretreia Culture: Roman copy of Greek original painting (this mosaic depicts Alexander as he is conquering Dorias) Location: Pompeii Date: ca. 100 BC (original painting: ca. 330-315 BCE) Format: Mosaic Medium: Stone, cement Alexander Mosaic: Detail of Alexander Artist: Original painting by Philoxenos of Eretreia Culture: Roman copy of Greek original painting (this mosaic depicts Alexander as he is conquering Dorias) Location: Pompeii Date: ca. 100 BC (original painting: ca. 330-315 BCE) Format: Mosaic Medium: Stone, cement Cameo of Alexander Hunting a Bear Artist: n/a Culture: Roman Location: Pompeii Date: ca. 1st Century CE Format: Cameo (This is a small scale object. Cameos are made of multi-layered stones that usually feature a light layer on top of darker material. By cutting away some of the light material on top and exposing parts of the dark layer underneath, artists create these tiny relief images that we call "cameos.") Gem of Alexander with Thunderbolt Artist: n/a Culture: Greek Date: c. 300-250 BCE Material/Format: Gemstone (The image features the following attributes: Thunderbolt, eagle, aegis, and staff/scepter. The inscription "NEISOU" was added by a later owner of the piece. Gems are made of semi-precious or precious stones into which an image is cut. Gemstones were used as seals and were stamped for example into clay. They are small-scale objects.) Head of Alexander from the Athenian Acropolis Artist: n/a Culture: Greek Date: 330 BCE Material/Format: Marble Azara Hern Artist: n/a Culture: Roman copy of Greek original Date: c. 330 BCE (original) Material/Format: Marble (Herm bears the inscription "Alexander, son of Philip of Macedon".) Readings for Week II Sourcebook 11: John Keegan Alexander the Great and Heroic Leadership The basic thesis: This essay describes Alexander’s career in order to explore how historical context, personal qualities, and cultural resources helped him to succeed. Although this essay is mostly descriptive, we might summarize the central thesis like this: Alexander became a heroic leader because he almost always did was culturally necessary to play that role perfectly, whether it was in organizing the army or managing his advisors, motivating his soldiers or leading them on the battlefield, and in fact we might say that he wore the “mask of command” so faithfully that he actually became it. In Keegan’s words, “like a great actor in a great role, being and performance merged in his person, his life was lived upon a stage –that of court, camp and battlefield—and the unrolling of the plot which he presented to the world was determined by the theme he had chosen for his life.”(91) In order to arrive at this conclusion, Keegan explores many aspects of Alexander’s biography. He starts with describing Philip II’s influence on him before summarizing Alexander’s many conquests. He then describes the particulars of Macedonia, the geography, the culture and religion of the people, the army, and the staff, all of which Alexander had to negotiate in order to succeed. He then describes how Alexander interacted more broadly with his soldiers, how he led them on the battlefield and how he used oratory and his own conspicuous shows of bravery to motivate them. Finally, Keegan describes how Alexander’s “mask of command” has influenced other conquerors, and speculates as to why Alexander was exceptionally successful. Because this essay is purely descriptive and written rather engagingly, I’d recommend reading it for clarification on the lecture materials as it does provide a relevant redux of Alexander’s exploits. But to make this long essay digestible, I will attempt to summarize the main points of each section, providing the key quotes along the way. Alexander: The Father of the Man This section describes Alexander’s upbringing and the influence his father, Philip II and his mother, Olympias had on Alexander. Alexander inherited his father’s ambition. His parents ensured that Alexander learned “Homer, whose celebration of the Greek heroic past was to determine Alexander’s approach to life. Disregard for personal danger, the running of risk for its own sake, the dramatic challenge of single combat, the display of life-and-death courage under the eyes of men equal in their masculinity…”(15) Alexander learned from Aristotle and from his father’s own exploits, as Philip had, after all, “acceded to the throne of a kingdom…of the Greek states, Athens, Sparta and, more recently, Thebes…[by] continuis campaigning he had brought the northerners to heel; imposed Macedonian power over Thrace…Thessaly…had himself nominated overlord of an invented alliance of Greek States.” (15-16) More importantly, he saw how his father organized and led the army, and Alexander, too, would participate in warfare starting at the young age of 16 and Philip gave him immense responsibilities shortly after. Indeed, “Alexander would have watched narrowly how his father manipulated the ambitions and antipathies of his followers. But the deepest of paternal effects upon him flowed from exposure to responsibility.”(20) The Achievement Alexander began his campaign in 335 and went on until 325 BC, with major battles almost every year. He conquered secured the areas in Greece his father had not. He then marched south toward Persia in order to invade the Persian Empire, a popular cause because “free Greeks feared and hated the Persians as instruments of a despotic power bent on robbing them of liberty and reducing them to subject status, so as a war leader Alexander took the “Role of his civilization’s champion.” (23) He then engaged his army against Persia, first beating Memnon at the Granicus. He did this despite the fact that Memnon had better position—Alexander simply sensed that his troops had more courage, and he charged Memnon right where he was strongest, and Alexander defeated him. Likewise, at the Battle of Issus he defeated Darius by sensing “moral infirmity” (26) Alexander then marched down the Mediterranean coast, won a bloody war at Tyre, and marched into Egypt before marching up to Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) to fight Darius again. They fought at Gaugamela, where despite being outnumbered, Alexexander won by employing an ‘oblique order’ that enabled Alexander to surround Darius’ troops again and utterly destroy Darius’ forces. This left Alexander as a Great King. The Kingdom of Macedon This section describes the natural resources Alexander inherited when he was born. Macedonia for all intents and purposes was a monarchy, and the monarch “was chief intermediary between his people and the gods”(32) Philip left Alexander the control of much of Greece. The main goods at Macedonia were timber and minerals, horses and grain. Philip had built an irrigation system that made the region fertile. The Macedonian Army The Macedonian Army, as Philip organized it, was formidable. The innermost core of the army was the Companian Cavalry, composed of Macedonians who belonged to a heroic society and keeping the regard of “such men” required “the war leader had constantly to excel – not only in battle but in the hunting field, in horsemanship or skill at arms, in love, in conversation, in boast and challenge, and in the marathon bouts of feasting and drinking…”(35) The army also had Foot Companions, which was an infantry force that provided solidity to the battle line. In addition, there were light cavalry that operated on the flanks, and there were specialty troops (e.g. archers). The Foot Companions used sarissas (18 foot spears). The Companion Cavalry charged in a disciplined wedge formation. Alexander’s Staff Alexander took good company with him including “surveyors, secretaries, clerks, doctors, scientists, and an official historian –Calisthenes—a newphew of Aristotle.”(40) Alexander sometimes consulted a general, Parmenio, only to do the opposite of what Parmenio recommended. He was frequently in conflict with Parmenio (see summary of ‘Loneliness of Power’ below for better discussion of specifics). Alexander and his Soldiers His soldiers followed him primarily out of loyalty and because of tradition. But Alexander led them “by indulgence as well as by example.” Examples of indulgence include letting his soldiers go home for a little while following the battle at Granicus, and canceling debts during the Indian campaign. Moreover, he also considerate of his soldier’s welfare. He made sure they had eaten, for example, before the battle at Issus. Before Gaugamela, he had made sure his soldiers had rested. After battles he visited his soldiers and talked to them about their wounds. He also made sure to dispose “decently of those who succumbed to their wounds, friend and foe alike.”(46) Ceremony and Theater An important point is that “theatricality was at the very heart of Alexander’s style of leadership, as it perhaps must be of any leadership style.”(47) He performed religious rites every day as “his day began with his plunging of a blade into the living body of an animal and…uttering of prayer as the blood flowed.”(47) He would hold athletic and literary contests. These were not only to mask battle horrors, but to enhance his image as he “was in the strongest sense a brilliant theatrical performer in his own right. Not only were his appearances in the field of battle dramatic stage entries, tellingly timed and significantly costumed, but he also had the artist’s sense of how to dramatize his own behavior when the mood of his followers failed to respond to reason, argument, threat or the offer of material inducement…”(48) An example is the taming of Bucephalus. Another example is how he responded after he killed Cleitus and actually gained more influence (see ‘loneliness of power summary for more). But, “at the very top of Alexander’s range of theatrical performances was his dramatization of the natural occurrences of sickness and sleep.”(51) For example, after he was wounded in India, he allowed the rumor to spread that he had died, so that when he reemerged it was enormously dramatic—a “resurrection scene.” (52) The scene when he emerged from visiting the oracle of Zeus Amnon at Siwah was also dramatic, as the oracle allegedly called him Son of Zeus and this was overheard by his entourage. Alexander gained yet more cache. Alexander’s Oratory Alexander frequently gave speeches before battles in order to motivate his troops. For example “before the Granicus, his exhortation took the form of a dialogue with Parmenio.”(56) Before Issus he gave a speech that invoking the “racial superiority” the Macedonians had over the Persians. He sometimes failed, however. When he was in India, for example, he wanted to keep going and gave a speech to this effect, but was outspoken by Coenus “who had the crowd with him from his opening words.” (57) Alexander on the Battlefield All of Alexander’s theatrical skills were directed toward having success on the battlefield. And his theatricality carried onto the battlefield itself. “For an encounter with the enemy he dressed in a special and conspicuous style…Alexander led in the precise sense of the word, and he needed to be seen and recognized instantaneously.” He dressed accordingly with an immaculately shined iron helmetand double layered linen body armor. He carried with him”the sacred armour he had taken from the temple of Athena at Troy, reputed to be relics of the Trojan war.”(61) Right before battle would begin, he would mount”the famous Bucephalus.” He was frequently wounded, which added to his legend. He actually gained wounds with more frequency when he conquered more places, and Keegan suggests that “the increasing frequency with which Alexander was wounded…implies a growing sense of desperation in his leadership.”(62) Alexander led many battles. Keegan then on pages 65-78 describes in minute detail precisely how Alexander employed theatricality, oratory, etc. in the battlefield, including the examples already described above. Alexander and the Mask of Command This section (pages 87-91) is mainly a rehash of what Keegan has already said. For literary reasons, it is worthwhile to read. No summary can do justice to this section. Keegan finally provides the thesis to this essay, which I have provided at the beginning of this descriptive summary. SourceBook 4: Ernst Badian, “Alexander the Great and the Loneliness of Power” The basic thesis of this essay is that in order to enhance his power, Alexander would not fret to betray his own Macedonian officers and manipulate his troops, even though these moves made him increasingly lonely. More specifically, Badian posits that the tumultuous circumstances surrounding Philip’s death that caused Alexander to inherit the Macedonian Empire at a young age made Alexander’s reign at first tentative. In order to strengthen his hold on the Empire, Alexander employed stratagems to diminish the influence of potential usurpers – the strongest Macedonian officers. In Badian’s words: Alexander “asserted independence and became King in fact as well as name.” Alexander did this using intelligence, charisma, guile and, when necessary, utter brutality. While he became more popular and powerful using these stratagems he also became more of a megalomaniac and distanced himself from those closest to him. This is the story: When Alexander first came to power, he wiped out the army of his main rival Attalus. Alexander saw Parmenio and his family as posing the next most serious threat to his reign. Thus, although Parmenio was one of Alexander’s best generals, Alexander never trusted him. Further, the more conquering and traveling Alexander did, especially inward and onward from Persia, the more his nobles simply wanted him to lead the troops back home. Alexander was as skillful at overcoming these political challenges as he was in winning military battles. This is particularly well illustrated in how Alexander eliminated Parmenio. As Alexander accomplished military successes, Alexander circulated rumors about Parmenio that Parmenio was more cowardly than him, (e.g. when Darius offered a reasonable treaty offer, Parmenio allegedly said he would accept it while Alexander pointedly said “I would too, if I were Parmenio.”) Further, Alexander also almost invariably gave Parmenio the difficult task of holding the opposing armys main wing, while Alexander led “the decisive breakthrough on the other.” Thus, Alexander, being a winner, won the loyalty of the troops. Once they conquered Media, Alexander left Parmenio in charge of supply lines. Alexander did this because he did not need Parmenio’s help anymore and because he wanted to get “rid of this overpowering presence.”(196) When the circumstances arose, this allowed Alexander finally to have Parmenio assassinated, and to justify this action on the basis of an elaborate lie. When one of Parmenio’s son’s died, another of Parmenio’s son’s (Philotas) stayed for the funeral. Philotas was then quickly put on trial for being implicated in plotting treason, and he “was condemned and at once executed.” (197) Alexander then had Parmenio assassinated with the posthumous accusation that he too was implicated in treason, with the “evidence” that his son confessed his father’s guilt. How Alexander overcame the threats of his own travel-weary nobles also demonstrates Alexander’s skill in getting and keeping what he wanted: power. In this connection, Badian provides three examples, First, Badian provides the example of how Alexander enhanced his power after he slaughtered Clitus, the man who had saved Alexander’s life in India. Both Alexander and Clitus were drunk at a party, and when Clitus said something Alexander did not like, Alexander “killed Clitus with his own hand.”(197) Alexander then theatrically grieved and fasted for several days until he was finally coerced to eat and to rule. Alexander became a sympathetic figure, and Alexander transmuted sympathy into loyalty. And this leads to the second example. Shortly after this episode, Alexander started taking on the trappings of a Great Persian King, and demanding that even his own Macedonian officers bow before him. When the Greek Callisthenes, laughed at this hubris, Alexander was chastened—and later had Calisthenes murdered on trumped-up charges. Third, when the army, led by Coenus, one of Alexander’s elite marshals refused to march further into India, Alexander tried to browbeat and grieve, but when this failed he had them march back on a tough route and fight frequently. The circumstances surrounding Coenus’ death, according to Badian, are questionable. Further, according to Badian, Alexander felt betrayed by his own Macedonians, and this is why he wanted to create an empire of mixed race—“the creation of a royal army of mixed blood and no fixed domicile…who knew no loyalty but to him”(201)—and forced his Macedonian soldiers to take Iranian wives in 324 BC at Susa. When his Macedonian soldiers finally threatened to mutiny, Alexander finally allowed them to go home. Badian describes how these actions made Alexander lonely, and how he dealt with this loneliness by becoming increasingly megalomaniacal. In 324, he “sent envoys to Greece demanding that he should be worshipped as a god.” (202) He “wanted deification for psychological and not for political reasons.” When his best friend Hephaestion died, Alexander wanted him to be worshipped as a demigod. In 323, finally, Alexander died and was so selfcentered that he would not name any successor. Thus, “the story of Alexander the Great appears to us as almost embarrisngly perfect illustration of the man who conquered the world, only to lose his soul.”(204) In short, Alexander illustrates with startling clarity the innate loneliness of extreme power. Week 3 Readings (note: Sylvan Barnet’s “Writing about Art” and “Analysis” are not reviewed. I wrote Yuhan, who said these will not be tested, but their material should have been internalized. As we all wrote paper one using Barnet’s work, I think we’re set on this one). Romm, Chapters 1 and 2, pp. 1-32 Chapter 1 (based on Plutarch) Plutarch only source on Alexander’s upbringing - very supernatural / romanticized Alexander born the day the Temple of Artemis was burned down by a madman - also the day of other victories for Philip II, prompting seers to say that, since Alexander was born on the day of a triple victory, he will be invincible - Alexander born to Philip II and Olympias Alexander had a slight leftward tilt of his neck, a moistness of his eyes, and a sweet fragrance. Alexander was very mature as a youth, and was not interested in bodily pleasures. He is famed to have said that he would race only with kings. Alexander was able to tame Bucephales, who reared at seeing his shadow. This won Alexander a bet with his father, who with pride said that Alexander could not be contained by Macedonia. Bucephales carried Alexander all the way to India. Alexander fought in battles with his father, and led a wing against Athens and Thebes. When Philip II became too drunk and Alexander became enraged, Philip II exiled Alexander and his mother. Only Alexander was allowed to return. However, Alexander’s friends, also banished, were not, until Alexander became King. At a great festival, Philip II portrayed himself as the 13th Olympian God in a gold statue. At this same festival, Philip II was assassinated by Pausanias. Pausanias had sought the King’s (sexual) love and had been rejected in favor of another Pausanias. The other Pausanias having died defending the King in battle, the rejected Pausanias was taken as a bodyguard for the King. Nonetheless, Pausanias murders the King, perhaps at the behest of Olympias, Alexander, or another party. Pausanias was slain immediately after the murder (perhaps a cover-up), so the truth is unknown. Chapter 2 (based on Arrian) Alexander’s first challenge was to subdue neighboring restless tribes - Alexander awed his enemies by crossing the Danube by night without the aid of bridges - it looked as though Alexander was trapped, but his superior strategy and discipline won the day - once victorious, Alexander sacrificed to the Danube, to Zeus, and to Herakles Then, the Persians incited revolts in Thebes and Athens - Alexander slaughtered the inhabitants of Thebes - Arrian says that the destruction was to punish the city for past “sins,” such as siding with the Persians during a great Persian invasion, but it is more likely that Alexander punished the city for resisting. Of Athens, Alexander demanded Demosthenes and Lycurgus (two orators), but relented when Athens refused. He probably did so in order to preserve the favor of the Greeks, whom he would need for his next conquests. Readings James Romm, Chapters 6-9 1) Philotas Affair and Killing of Parmenio a. Bessus, as one of Darius’ murderers, was the only possible Persian left who could claim rule of the Persian Empire b. Alexander hunted him down to kill him c. The tension of the rugged terrain of the hunt led to unrest among the troops and to the Philotas trial d. Philotas was the son of Parmenio, the senior general who had serves as philip’ sand Alexander’s second in command- he was accused of hearing about a plot to assassinate Alexander but not doing anything about it i. He was found guilty and Alexander ordered him and his father killed as a result 2) The Capture of Bessus a. Philotas and Parmenio were killed and Alexander’s officers in Media had passed a major test b. They now continued the hunt for Bessus c. He was hiding in Sogdiana, but after the king learned of Alexander’s fast advance, he gave Bessus up d. The account of the punishment of Bessus is detailed and shows the changes taking place in Alexander’s character and behavior 3) The War with Spitamenes a. In 328 and 327, Alexander’s forces in Bactria and Sogdiana were harassed by tribal guerrillas under the command of Spitamenes, the former head of Sogdiana b. These geuririllas did some of the worst damage to A’s army c. This war forced Alexander to develop new tactics and strategies d. Army morale fell dramatically through these battles 4) Death of Cleitus a. The death of Cleitus, the son of Dropides, caused Alexander great grief 5) The proskynesis crisis a. Another one of Alexander’s moral transgressions—he attempted to enforce proskynesis, which was a Persian display of respect, performed by bowing low before a person of high rank b. The Greeks hated this tradition, but the Persians were used to it c. Alexander wanted the practice to be done to him, which implied that Ammon, not Philip, was his father 6) The Sogdian and Chorienian Rocks a. The leaders of these two areas were ruled by adherents of Bessus, who refused to give in to Alexander 7) 8) 9) 10) 11) b. He conquered Sogdian by marrying its king, Oxyartes, to one of his daughters c. Oxyartes then convinced the king of Chorienian to submit to Alexander The Invasion of india a. Sodiana was now totally under control of Alexander, so he decided to further his journey into India b. At the time, India was virtually unknown to the Greeks, and it is unclear why Alexander wanted to conquer them—says “a longing seized him” to do so c. He hauled his army of 100,000 across the Hindu Kush in 327 to India—his men never expected or desired to go here Nysa Rebels a. Alexander attacks Nysa b. They send their “wisest and best citizen” named Acuphis to try to convince Alexander to leave the city c. He was impressed with the man and granted the city its freedom d. He appointed Acuphis governor The War with Porus a. Entered modern day Punjab b. Made an agreement with Taxiles that provided Alexander with a base in Taxila in exchange for assistance in overcoming Porus, Taxiles’ enemy to the east c. This resulted in Alexander’s last and greatest battle, the battle of the Hydaspes d. Arrkian notes some of the discoveries made in India by A’s army e. The Indians used elephants in battle, which proved difficult to deal with and caused heavy casualties f. After a long battle, Porus came to meet Alexander and impressed him with his good looks and incredible height (8 ft). g. Alexander was pleased with Porus and granted him sovereignty and gave him even more land than he had had before h. He got Porus’ complete loyalty The Hyphasis Mutiny a. Abisares surrendered after Alexander defeated Porus and so did most other cities b. In India, Alexander decided to use tactics that would horrify and terrorize his enemies into submission i. Perhaps he was looking ahead to the difficulties of holding and governing such distant territories once he went home c. Many soldiers had served under Alexander for 10 years and were not happy when Alexander elected to continue into India and cross the Hyphasis into a territory with a good army, monsoons, and more elephants d. Alexander has to give a speech to rally the troops The Indus Voyage and the Attack on the Malli a. Alexander gave in to his army and decided to take them home 12) 13) 14) 15) 16) b. He planned, however, a route that would take them down the Indus River and into territory controlled by the most entrenched, virulent anti-NMacedonian opposition ever encountered in India c. The army proved reluctant to fight and actually disobeyed orders to scale the walls of the resisting Malli towns, this caused Alexander to do it himself and exposed himself to a near death, heroic experience i. He managed to live after being seriously wounded ii. The soldiers were devastated bc they thought he had died and didn’t believe he had actually recovered until he was able to show his face d. He was in bed for 5 months recovering from the ordeal The Gedrosia March a. Sent a fleet along the “great sea” that would sail along the river as he would march on land and meet periodically b. The Gedrosian desert wsa said to have defeated all previous conquerors and Alexander, too, was not able to stick to his plan The Final Phase a. Alexander finally reached Carmania, where he could get supplies, but only a portion of the army was left after the desert march b. Some sources believe that 3 out of 4 men died on the journey c. Calanus dies in Persia The Susa Weddings a. In 324, Alexander arrives in Susa after losing much of his army in the desert b. He held weddings for himself and for his Companions c. He married Darius’ eldest daughter, Barsine, and another wife as well i. The weddings were held in the Persian manner, which angered his Macedonian troops d. He paid off all of his troops’ debts, no questions asked e. He bestowed a number of other gifts in recognition of rank or conspicuous courage The Mutiny at Opis a. The Macedonians were not happy with Alexander’s wearing Persian clothing and that the weddings were conducted in the Persian manner b. The Macedonians thought Alexander was becoming a barbarian c. Alexander brought his troops to Opis and announced that the troops who were old or handicapped could return home d. The troops were furious at him because of how Persian he was acting e. He decided to go into seclusion and dismissed all of his troops— f. The troops decided to come back and basically begged for reconciliation g. He hosted a banquet that night for everyone and wanted the Macedonians and Persians to enjoy concord and fellowship The Death of Hephaestion a. Hephestion fell ill abruptly and died b. Alexander went into mourning and didn’t eat a thing for days 17) Alexander’s Illness and Death a. After emerging from the grief of Hephaestion’s death, he craved new projects b. He approached the city of Babylon to adopt it as the capital of his empire and allocated a lot of money to rebuilding the temple of Bel in the center of the city c. As he was entering the city, he received signs of disaster awaiting him d. He ended up falling ill but performed his duties until he could no longer move e. His men all came to see him on his death bed f. When asked about his succession plans, he is said to have answered, “To the strongest man” g. Unfortunately, there was no clear successor—he had just gotten his wife, Roxane, pregnant but they didn’t yet know that it was to be a boy h. He may have wanted Hephaestion to succeed him but never made new succession plans after his sudden death i. Some historians, however, point to the lack of succession plans as evidence of his megalomania j. A compromise was reached where Arrhidaeus, Alexander’s mentally impaired half-brother, (renamed Philip III), was made co-regent with A’s unborn child and Perdiccas became regent for both k. Alexander’s son, named Alexander IV, never spent a day on the throne bc his mother and he were executed because of the power vacuum that A’s death left l. His top generals all jockeyed for power—when the dust settled, the Macedonian empire was broken into pieces m. It was most likely Alexander’s personality which kept the enormous empire together Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction 1) the article looks at two themes in Alexander history in which it is not easy to draw the line between what happened and what did not 2) The first theme is that of Parmenio’s advice, which proves more nuanced than is recognized a. The interactions bn the two of them portray Alexander as the heroic figure who makes the daring, brave choices after rejecting Parmenio’s more cautious advice b. His advice, however, is not always bad and A does not always reject it—on 5 occasions, he actually accepts the advice and was correct in doing so c. The context for Parmenio’s advice differs from author to author i. In some accounts, he offers unsolicited advice, in others Alexander asks for advice ii. The setting in which he gives the advice also differs from author to author d. It is difficult to doubt that he gave Alexander advice but one should judge each individual incident and the themes of each piece of advice on the plausibility of the advice e. The author decides that none of the accounts should be used as historical information i. It is possible that some of the incidients preserve material relating to actual decision-making in the reign of Alexander, but even in these cases, the literary quality of the theme may have been distorted f. The theme of the advice primarily involved speech and most ancient historians felt free to invent speeches and dialogue i. Ancient historians were much less likely to make up events and actions but speeches were likely contrived 3) The second theme called into question is the seclusion of Alexander in order to apologize to his troops a. Alexander secluded himself after committing violent actions toward Cleitus— ultimately, the tactic worked and his troops and associates begged him to return and excused his violent act b. ON the Hyphasis river, when the troops refused to cross, Alexander sulked and tried the same tactic, but this time was forced to concede most of his position c. At Opis, when his troops defied his plans, Alexander punished some and then once more secluded himself and again his troops begged him to return and be reconciled—he got most of what he wanted here d. Homer and Achilles were central to this theme and Alexander’s use of this strategy- they were his models for this behavior e. Generally accepted scholarship says that his troops begged him to return because they could not afford to lose him i. The reason why this actually worked after the death of Cleitus was not, according to this author, because the army couldn’t afford to lose him, but because his actions appeared to fit Homeric norms—the actions were excessive, as those of Homeric heroes were, but they were big, terrible on a large scale ii. The second incident failed at the Hyphasis because nature brought his men low and they could nt keep going. The first incident required his men to accept his behavior as existing within a heroic context, but the second required them to act in an heroic way themselves, but they were too tired to do so 1. It had nothing to do with the fact that his army needed him because his army needed him just as much in the second instance as they did in the first, but they refused to give in in the second example f. 2. In the second instance, his men did not consider Alexander’s situation comparable to that of Achilles, even though Alexander wanted them to iii. The third example, at Opis, was his most calculating and manipulative 1. His troops really did seem terrified to be cut off from their relationship with him and desperate to restore it 2. The men at Opis seemed like excluded lovers, jealous of their Persian rivals 3. Also, in the third incident, much more than the first and second, the men really did need him. The arrival of the Epigonoi made it clear that they were expendable and Alexander called their bluff 4. This, too, was Homeric These three examples are significant because they show the importance of Homeric values to Alexander and his men. They also speak to Alexander’s selfconscious manipulation of his own Homeric image and his ability to impose his will onto others WEEK 3 LECTURE NOTES Lecture Notes 10/1 Lit & Arts B-21 Notes 10-1, 2007 In Athens and other city-states there was a great amount of slavery. Macedonia was developmental. A Question is were the Macedonians Hellenic or barbarians, did they speak a non Hellenic language. Some of their names were not Hellenic. Alexander’s companions speak a type of rogue language. There were lots of horses and horse names in Macedonia. For the longest period of tie, Greece was known for its wine, and became wealthy on its fine wines. The famous mountain in Greece was Dyon. The Macedonians had a dynasty of rulers. One was the Tyanan (???) dynasty. The Macedonians may have been very beloved by another group of people: The Macedonians. Another area important was Eporia, that is where A the G’s mother was from. Beginning in the 5th century we find coinage from Macedonia. It has Alexander the 1st on it. He was Alexander the Philhellene. What was “medizing”??? On the coin, he is depicted on the horse and carrying a spear. People would horde their money. It was how they kept their money safe. While this was going on, Athens was at its highest power, being run by Perakles. Athens was prospering. . They collected money from other countries. But, by 404 Sparta had defeated Athens. Archelaos came to power then, he was a patron of the arts. He brought in Euripides (the third of the great playwrites). His last play was the Bacchae, showing how much people wanted to be in Athens. In 359, Philip used the companion cavalry comprised of hoplites to defeat the Greeks we have an image of Philip, from the bottom of a pan. He had a beard. He had been struck by an arrow in the eye and had lots of wounds. Alexander would take a lot of wounds, too. The wounds symbolized their bravery and their prowess, and their divine right to rule (because they escaped death?) A series of marble sculptures of Philip were created by the Romans. Many Romans emperors believed themselves to be reincarnations of Alexander, putting pictures of Philip and Alexander on their coins. We have three great concerns by the Macedonians (Hunting, war, abduction). The city of Olympus was important, but when Olympus allied with Athens, Philip ruined Olympus. We have excavated Olympus, and we have found it to have been a planned city, with even-sized houses, and a grid of avenues. There were also sling bullets. We have found sling rocks. Most of them were from Crete. They wrote on them. During the 4th century BC the greeks and others engaged in immense war preparations building walls for protection, etc. What the Greek troups held were Sarissa spears, 18 feet long. The greeks were in a constant state of training. They were prepared, and they had good leadership. In his minting of gold and silver coins, The great Athenian speaker Demosthenes called Philip a barbarian because he drank his wine straight without a spritzer. In 336, when Philip celebrated the marriage of a half sister, he showed up himself, and was assassinated. A the G himself killed the assassins. A the G would free the greeks from the Persians, which is what he would do. Good Quote: “It is noticeable how in politics as in fighting Alexander’s character appears consistent and unmistakable: never rushing things, always carefully planning further ahead than the enemy could see, but never missing the chance of striking the decisive blow when it presented itself, and then leaving the enemy no hope of resistance or recovery.”(197) Week 4 Lectures Alexander in Asia Minor and the Levant Alexander crosses the Dardanelles, one of the two strategic straits of Asia Minor. In the strait, Alexander pours massive libations to the gods, hoping to meet success beyond that of the heroes of the Iliad (contrast with Xerxes, who in his hubris, lashed the water for destroying his bridges). Upon crossing the Dardanelles, Alexander hurls his spear into the Asian sand, and proclaims that Asia is “won by the spear.” Alexander visits Troy and makes sacrifices and visits the tumulus of Achilles and Patroklos, who Alexander sees as mirrors of him and Hephaisteion. Alexander also sacrifices to Hector and Priam in an attempt to make peace with the angry spirits of Troy. Alexander engages in his first major battle at the Granicus River. His primary opponent is Memnon, a former Rhodean in the service of the Persians. Memnon and his Greek mercenaries fight fiercely, but are routed along with their Persian counterparts. Alexander was trapped and almost slain, but Cleitus saved him. After the battle, Alexander commissioned Lysippos, his most trusted sculptor, to sculpt 34 cavalry statues to honor the 34 Companion Cavalry who perished in the battle. Alexander won the favor of his troops by visiting the wounded and listening to their battle stories. Alexander continued to move through Asia Minor, stopping at Sardis and Ephesus (the city that housed Artemis of Ephesus’ great temple, which was destroyed the day of Alexander’s birth). Alexander allegedly fought for the “freedom of the Greek cities” of Asia Minor, but cities like Halicarnassos challenged Alexander and refused to open their gates. Maussolos, King of Halicarnassos, fought bravely, but Alexander’s first great siege ended in complete victory and widespread slaughter. Upon reaching Gordion, Alexander sought the Gordion Knot; he who untied the knot was said to “be ruler of all Asia.” It is likely that Alexander cut the knot, and saw this as justification of his right to rule. Alexander in the Levant and Egypt Alexander turned his forces south after possessing a portion of Asia Minor, and streamed into the Levant and Cilicia. This region celebrated a God, Baal, which Alexander believed was Zeus. Baal was put on the reverses of Alexander’s silver coins. Alexander became trapped by Darius III and the Taurus Mountains, precipitating the Battle of Issus. Alexander succeeded in turning Darius’ flank, routing the Persians. Here Alexander captured great wealth and some of Darius III’s family, including his mother. Alexander continued to move south. Sidon opened its gates to Alexander. Remarkably, Alexander found Abdalonymus, a humble descendent of an ancient king, whom Alexander restored to Sidon’s throne. This King’s coffin was found in the 1880s and is called the “Alexander Sarcophagus.” Alexander met great resistance at Tyre, which Alexander laid siege to for five months after the city refused to let him visit the statue of Melkart. Alexander believed Melkart to be akin to Herakles (syncretism), his ancestor. At Tyre, Alexander proved his siege genius, building moles, catapults, rams, and brilliance to counter the Tyrian’s fireships and fortified walls. Alexander conquered city after city, taking Damascus and Gaza (the ruler of which Alexander dragged around on a chariot, or so it is alleged), and reducing Darius III’s ports so that the Persian navy would be rendered worthless. In Egypt, Memphis crowned Alexander as Pharaoh. Alexander treated the Egyptian gods with great respect, especially the Apis Bull, and won the affection of the Egyptians. The Egyptians already bore a strong disliking for the Persians. Alexander laid the grid for the greatest of his Alexandria’s (using his soldiers’ rations to demarcate the city’s boundaries!) and made a substantial diversion to visit the holy place of the Siwa Oasis, in West Egypt. There, Alexander is thought to have received confirmation by a priest of Zeus Ammon (a composite of Zeus and the ram god Ammon) that he was divine or of divine ancestry. QuickTime™ and a TIFF (LZW) decompressor are needed to see this picture. QuickTime™ and a TIFF (LZW) decompressor are needed to see this picture.