Unit 2: Setting the Stage for the 4

advertisement

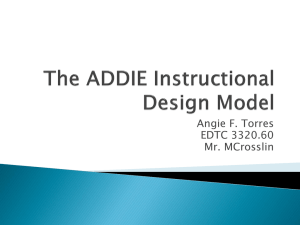

Unit 2: Setting the Stage for the 4-Steps Introduction As covered in the previous chapter, you are exploring the concept of instructional design and what it means to be an instructional designer. The comparison made earlier between an instructional designer and a puppeteer should help you start with a different perspective. As a puppeteer, you are not always on the stage; often your ideas are on the stage instead. In order to get to the point where you are able to act like a puppeteer you must consider a number of variables important for learning. A 4-step design process is introduced that will direct you through the rest of the book and the class. Before the process is shared you will learn the context of the 4-steps, which is just as important as the 4-steps themselves. This chapter consists of 6 parts: Part 1: why the 4-steps are needed, Part 2: analysis prior to the 4-steps, including a brief description of performance analysis, instructional intervention analysis, and intervention analysis Part 3: the fractal nature of the 4-steps and why it help us learn about the larger design process (which explains how the 4-steps match other design models as well as work to create both micro and macro instructional units) Part 4: ADDIE, the four steps, and the puppeteer (later chapters cover each step in detail) followed by a description of a number of instructional interventions that can be developed using the four steps. Part 5: A review of information processing theory (which explains how cognitive load can be enhanced by helping people select, organize, and integrate information for meaningful learning Part 6: Your job of a designer (which explains how to implement Parts 1 - 5) 1 Part 1: Why the 4-Steps are Needed Structuring or designing information for learning requires skills different from traditional teaching practice. The 4-Step process helps you create instruction that allows a facilitator to be a guide on the side to optimize student-to-student interaction, student to content interaction, student to teacher interaction, and student to interface interaction. Notice how differently learning is described? For one, the word interaction suggests some type of exchange between two entities. The teacher and learner are not passive, they respond to each other. Additionally, that exchange is not limited between a teacher and student, as it has been in the past. Given the changing nature of learning that has been established up to this point, the 4-Step process is recommended as a method for creating a learning environment, a learning space that encourages interaction between teachers, students, content, and the interface. 2 Part 2: Front-end Analysis Needed Prior to the 4-Steps Before getting into the 4-Steps though, something needs to happen before creating instruction. In order to set up an optimal learning environment, you must analyze the need for training or education in the first place. It could be that education or training is not needed. Let’s take a real-life example. Imagine yourself in a different role than the one you have now, you are in charge of timemanagement training for the people with whom you work. Your supervisor noticed that your department was not as productive as needed and asked you to give a quick workshop. You decide to do a quick analysis of your peers, so decide to take a day or two to observe your work setting, something you have never taken time to do before now. To your amazement you discover that your peers do not need a time management course, they simply need to move a coffee pot! When you were asked to do the training, you assumed that you would be covering things like setting goals and priorities. Perhaps introducing concepts behind a principle-driven life (Steven Covey comes to mind). After observing the work setting for several days, however, you discover that your peers are spending an unusual amount of time congregating around the coffee pot and chatting with the gregarious and entertaining secretary. Moving the coffee pot to a less entertaining location ends up being a solution to the "problem." This is a true story, shared with me by a student taking this course several years ago! This story introduces a new way of thinking about training and education. Maybe you should not train! Training may not be the solution to a problem. You might think “but I need to teach my content! I want to know how to teach -- not about these other things." Again, try to remove yourself from the traditional connotation of your job. You are an instructional designer - a detective of sorts. Performance Analysis and Training Needs Assessment A front-end analysis is conducted to determine if other approaches to a problem might be more effective, and often less costly to pursue. Front-end analysis helps prevent extraneous load by identifying only the most crucial information needs. In many situations (as in our coffee pot story) education and training are not needed, instead there is something else in the 3 environment that must be addressed. Perhaps management and administrative issues introduce performance problems. Factors that contribute to motivation, organization work processes and the like are barriers to workplace performance. Management, administration, motivation, work processes and other nontraining issues are analyzed using a process called Performance Analysis. If a performance analysis indicates training is needed, a training needs assessment is conducted. Training needs assessment addresses gaps between what a learner already and what they need to know. If you desire to learn more about these topics you can find a number of textbooks dedicated to the many steps and processes needed to conduct analysis (see the For More Information section of the Unit 2 Web Site). Intervention Analysis While we do not conduct a performance analysis or a training needs assessment, we do take the time to analyze the type of instructional intervention needed. The word intervention is used because it stands for training/education but is actually something that intersects between where the learner starts and where they end. Think of the saying "Moving people from point A to point B". This means we help people learn something in order to move from where they are currently (point A), to a place we think the learner should be (point B). The piece in-between A and B is an intervention. It is what we do. This entire class is all about creating an intervention or a set of interventions. We will use Clark and Estes (2002) four-part intervention model which defines an intervention as a strategy that helps close the gap in knowledge and skills. Interventions types include information job-aids training education (Clark and Estes, 2002). For the most part, the interventions in this list are increasingly complex. Information interventions include presenting raw data. Think of an encyclopedia, a phone book, some textbooks that do not employ strategies to make their information meaningful. Information Interventions When do you need an information intervention? According to Clark and Estes (2002), you provide information when a person’s past 4 experience does not contain the knowledge needed to perform in their work or learning environment. For example, if someone is worried about the West Nile Virus, and has never learned the symptoms of the disease, they will seek information. Perhaps they will go to the Internet, or to the local library. The person wants facts and data. They want to read or hear an audio recording of the information. The Help file in your word processing software provides one example of an information intervention. If you look up the word “copy” you will learn what “copy” is. For example the help file might say “To duplicate information use the “copy” command. The copy command keeps specified information into a memory buffer to be used later when a “paste” command is executed.” When you design information interventions, you do what you can to reduce the intrinsic load. You may permit some forms of load that could be considered extraneous (such as examples), however your focus will be on reducing the complexity of the content. Your strategies will focus on optimal sequencing of content. Job-aid intervention Job aids go beyond information and are provided when the person does have experience or some knowledge, but that experience isn’t clearly similar to the task the learner needs to perform, or the learner does not remember all of the information needed to do their job. Job aids organize the information to help people do jobs easily. Think of them as organized information. Let’s go back to the Help file example. Help files also contain job-aids. The difference between information and a job aid is that a job aid is organized according to the user’s task and it makes it very easy for the user to follow. For example, if there is a page in the help file titled How to Copy, and that page shows clear steps on performing the copy function, then that page can be considered a job-aid. For example the following information can be considered a job aid. How to Copy Information 1. Highlight the information you want to duplicate. 2. Select Edit > Copy 3. Move your cursor to the location where you want to paste the copied information 4. Select Edit > Paste 5 Other common forms of job aids include one page instructions on how to operate a machine, recipes, weather reports in the newspaper, a sign in a grocery store telling you where to find pasta, and many other sources of information that are displayed in a highly organized or structured manner. You use cognitive load theory to help you design job-aids by presenting only the most critical content, organized by task. Essentially you remove as much extraneous and intrinsic load as possible. Training Training goes beyond a job-aid and is provided when the knowledge or skill needed is not familiar but is fairly procedural and requires guided practice. Training works well for step-by-step instruction of new information. Training is required for more complex information and tasks. While a job aid is helpful for some information, training is required when that information is lengthy or challenging and practice is necessary. For example, the craft of metalsmithing is one that must be trained. The information is complex and years of practice with a skilled artisan are required. Let’s go back to the “Copy” example for a more typical situation. A person would unlikely attend training on the Copy function, but they would attend training on an entire Word Processing program if they were novices in the topic. Cognitive load theory applies to training interventions as well. Well-organized content with practice activities focus on reducing intrinsic load and providing opportunities to increase germane load through practice. Education Education is the most complex intervention of all and is required when a person needs enough knowledge or skill to anticipate and solve novel problems in the future. Learning a word processing tool can be considered education when the learning experience includes opportunities for the learner to apply the new information to novel situations. Type of intervention covered in this textbook In this class, you will be involved in training or educational intervention. Your primary responsibility is designing an environment where people learn, not just perform. Your focus is especially oriented towards increasing germane load. 6 You may create job-aids to help people with tasks that do not require deep learning; you may use information interventions as well. Another book and class teaches how to design messages to facilitate learning, which is covered in another course ET504 and ET604. In this book, we take a micro view of the 4 - step process and create a module or unit of instruction, something that might take only ½ hour for a learner to complete. The 4- step process, however, can be used to create an entire curriculum. When designing a curriculum, the focus of each of the 4-steps is similar, but the scope changes. By learning the 4-steps you essentially learn the skills needed to create an entire curriculum. Those same 4-steps also help you zoom all the way down to the most microelements of instruction - the objective. The structure for writing a single lesson objective is similar to the structure for creating an entire curriculum. The 4-steps is a good place to start, when you are ready to tackle larger projects you will want to move on to the classic instructional design texts: Dick and Carey's (2006) Instructional Systems Design (a rigorous approach that involves an intense goal analysis complete with strategies for identifying prerequisite knowledge). Smith and Regan's (2006) Instructional Design (an in-depth review of instructional strategies associated with different content classification schemes) Morrison, Ross, and Kemp's Designing Effective Instruction (a 9-step model known for its emphasis on non-linear design processes). (If you are interested in learning these approaches, ET702, is a class you might like to take.) 7 Part 3: The fractal nature of the 4-steps and why it help us learn about the larger design process I share the above classic textbooks to illuminate the nature of instructional design. The reason this book is accepted for publication rests in the complexity of these other textbooks and a widespread dissatisfaction with their use. Cognitive load when reading these textbooks tends to be very high. The 4-Steps are similar the classic approaches due to the fractal nature of the design process. Fractal theory describes objects as having a self-similar composition under changes of scale (see Figure 1 on the next page). 8 9 As shared in Figure 1, there are many examples of fractal theory. If you think about it, movies, plays and textbooks have fractal natures, due to the beginning, middle and end of scenes that fit into acts and so on or into the composition of textbook chapters and textbook sections. While these examples represent tangible products, fractal theory is also evident in the processes involved in creating the products. Our puppeteer follows a process when creating their plays that is very similar to the process used to create instruction. Figure 2. An instructional designer as a puppeteer 10 Part 4: ADDIE, The 4-Steps, and the Puppeteer Instructional designers typically follow a process that has a generic name, ADDIE (Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation). When designers create they first analyze the learner problem, they generate ideas and create a design, they develop the design (instruction) fully, they test or implement the instruction, and then evaluate the instruction and the design process. The ADDIE acronym represents the design process. In this book we substitute ADDIE with an abbreviated 4-step process (to reduce your cognitive load) and make the information more germane. The four-step process includes these steps: 1. Sizing up the learner 2 Stating the learner outcome 3. Making it happen 4. Knowing what the learner knows The four steps are similar to ADDIE. Table 1 helps you compare ADDIE to the 4 - steps and to the puppeteer analogy. Table 1 Comparison of ADDIE, 4 – step model, and Puppeteer Analogy ADDIE 4 – Step Model Puppeteer description The Analysis step 1. Sizing up the Identification of an corresponds to learner audience Sizing up the (Who is your learner audience? What type of context do they work in that might influence the content you present?) The Design step 2. Stating the Identification of the corresponds to outcome critical message. Stating the (What do you want the Creating a script that outcome and learner to be able to will communicate your creating do and understand message instructional after they receive objectives. training?) Development and 3. Making it happen Presenting a story with Implementation (How will you engage a beginning, middle, correspond to the the learner in a way end, introducing a Making it happen. that achieves the conflict, characters, outcome stated and a conflict above?) resolution. Conducting 11 Evaluation corresponds to Knowing what the learner knows. 4. Knowing what the learner knows. (Did learning take place?) rehearsals to refine the event. Effectiveness gauged by audience reaction, applause, ticket sales, and perhaps a changed way of thinking. 12 Part 5: Cognitive Load Theory and the 4-steps This final section of the chapter brings us back to the topic of the previous chapter - learning theory. Prior to this point we addressed cognitive load theory and the importance of decreasing the load placed on memory by increasing germane load and reducing extraneous load. We take up with where we left off by presenting Information processing theory, which describes the memory structure we work with. By enhancing the mind's tendency to select, organize and integrate information we are able to address the issues of reducing extraneous load and increasing germane load. Information processinig theory describes how information travels from sensory memory to working memory and finally to long-term memory. These three memory systems are often referred to as two types of memory - short-term (a combination of sensory and working memory) and long-term (see Table 3). Notice how information and job-aids fall into short-term memory and training and education fall into long-term memory. I make this distinction to illustrate the different memory goals of these learning tools. Your design focus for information and job aids tends to emphasize the need to facilitate short-term memory. By making information easy to perceive, we facilitate sensory and short term processing. Your design focus for training and education, on the other hand, tends to emphasize the need to move information from working into long-term memory. It may be easiest for you to think of information and job-aids as helpful to the short-term, to be used in an immediate sense and less important for the long run. Likewise you might think of training and education as helpful for long-term memory. Three Types of Memory Essentially we design for these different types of memory. This does not mean that information designed for sensory processing does not influence long-term memory, or vice-versa. It means instead that our design efforts focus on a particular memory system. The three types of memory are highly interactive. Just think of yourself driving and seeing the shape of a stop sign in the distance and how your foot unconsciously moves towards the brake. In this situation a perception of shape triggers longterm memory almost instantaneously. 13 Table 3: Sensory, Working, and Long-term memory Short term memory Sensory memory Working memory Long-term memory Long-term memory Information and job-aids Training and Education Even though memory is unlikely to be as compartmentalized as depicted in Table 3, it helps for us to think of memory as starting with what we perceive or sense (sensory memory) then moving into a working memory that further processes a thought and makes its way to long-term memory where it is stored forever. Memory is more complex than this because much of what we perceive never makes it into working memory, and from that point it may never make it into long-term memory. Additionally, we know that there some information is instantaneously and unconsciously remembered (as in the case of a stop sign) while other information is remembered only by focused thinking, such as using the acronym Every Good Boy Does Fine to remember notes of a music scale. Table 4 shows that capacity, duration, and format for the three types of memory vary. Sensory memory can hold an unlimited amount of information, but for a very short time, seconds. Working memory performs in an executive capacity by managing and manipulating information. Working memory is where we as designers must focus our efforts. We must structure information to “stay alive” in memory, long enough to make it to long-term memory. Long-term memory is unlimited, capable of holding an infinite amount of data for an indefinitely long time. According to theory, once information makes it to long-term memory it stays there forever. This would be great if most people could find that information when they wanted it! The problem in retrieving information from long term memory resides in how that information was stored. In other words, how effectively and efficiently the learner thought about the information - this is where instructional designers can focus our efforts. 14 TABLE 4 Capacity, Duration and Format of Long- and ShortTerm Memory Memory store Short-Term Memory Sensory Memory Working Memory Long-Term Memory Capacity Duration Format Can hold an unlimited amount of information. Can hold a very limited amount of information. Can hold an unlimitedamount of information. Seconds Visual and auditory Seconds Visual and auditory Indefinite, some think permanently Visual, language, semantically (in a summarized or overall gist rather than detailed, word-for-word manner) Understanding Short-term Memory - The Importance of Selection and Organization A big problem with most training and educational contexts is the lack of attention to the perception and learning barriers created by the limitations of sensory and working memory. Again, sensory memory holds an unlimited about of information, but just for a few seconds! If you are not convinced, stop for a moment and think about everything that your sensory memory is taking in now. Try to hear sounds around you that you’ve been ignoring. You might hear a fan, the compressor in a refrigerator, the hum of a printer, the voices of neighbors, or any number of sounds. Because you’ve decided to pay attention to your environment, you are suddenly conscious of things you were unaware of just seconds before. Look back at this page now. Your sensory memory is taking in a lot of information just on the page; it sees individual letters, words, paper, your hand, the edges of your book. Much of what you sense you ignore because your sensory memory has a filter that directs your attention only to certain things. For example, you don’t really pay attention to individual letters within a word; instead you attend to the word. 15 We name the process of attending to specific information and ignoring other information selection. Fortunately as the exercise above just illustrated, your mind does select and filter out a lot of unnecessary information, freeing you up to focus on only the most relevant, satisfying or interesting information. We name processes that take place in working memory organization. Working memory is also a short-term memory, but the capacity of working memory very small. Miller (1956) found that working memory holds anywhere from 5 to 9 units (7 plus or minus 2) of information. Recently, Cowan (2004) presents research suggesting 4 units. Cowan’s research suggests that as designers we may need to be even more concerned about finding ways to limit information overload. Both Miller and Cowan use the term unit to describe information that is chunked together. What comprises a unit varies according to how much information can be chunked together and still have meaning. It becomes very important to help learners/performers work with units that make sense to them. In other words, you want to create appropriate chunk sizes. This is where we begin to address individual differences, which we have identified as critically important to assessing optimal cognitive load. Novices typically need smaller information units (or chunks) than experts. Think of how a beginning reader first has to focus on very small chunks (individual letters that make up simple words). Reading materials for young children usually consists of very small chunks sizes. Each page has only one or two words. Experts, however, are able to use page-sized chunks because sentence and paragraph level chunks help them process the content. If you comprehend this passage, it is because your mind chunks letters into words so quickly that you don’t notice the words as much as their meaning in the context of a sentence. This is also true of sentences, experts tend to process the meaning of sentences rather than individual words. Greater expertise requires greater chunk sizes. Understanding Long-term Memory - The importance of Integration We call the processes involved in moving memory from short-term memory to long-term memory Integration. Moving information from working memory to long-term memory is usually the biggest challenge! Rehearsal increases the chance that information remains in memory, but the best bet for getting information into 16 long-term memory is by making the rehearsed information meaningful to the learner. Analogies and metaphor have long been used to do just that. By comparing new information to something the learner already knows, the learner is more likely to understand the new information. Whenever you can make connections to things within your audience’s experience, they are more likely to remember it. 17 Part 6: Your Job As a Designer As a designer your job is to design information with the three types of memory (sensory, short-term, and long-term) in mind. To do this you help the learner Select the most important information, Organize the information in a way that is memorable, and Integrate that information into memory, often by using metapahors or other strategies that help increase the likelihood that information is meaningful. The 4- Steps process is a process that helps you improve learner selection, organization and integration. Each of the 4-steps requires you to think carefully about learner selection, organization, and integration. Summary In the previous chapter you learned about cognitive load theory and the importance of creating a learning environment that addresses optimal load. You were introduced to the concept of instructional design and the analogy of a puppeteer, comparing your task as a designer to that of a puppeteer who creates a learning experience. This chapter addresses the importance of creating an environment that focuses on different learning requirements, be it the need for information, job-aids, training, or education either alone or together. This focus increases your odds of providing an optimal load at the onset. If a well-designed job-aid meets the goal, then you have optimized load by minimizing the amount and complexity of instructional content. The 4-step process was introduced as a road map to designing instruction. Although you follow the 4-steps to create a unit of instruction lasting approximately 30 minutes, these same 4steps, due to their fractal nature, can be used to create entire curriculums. Additionally you learned about Information Processing Theory and the different types of memory and the importance of structuring (designing) information to facilitate those memory processes. By helping a learner select what is most important, organize it in a memorable way, and integrate it meaningfully into memory in a meaningful way, you design for optimal load. 18 Know These Terms! Education interventions - any situation where there is a conceptual, theoretical, and strategic transfer of knowledge or skills that allow people to solve problems in new ways (Clark & Estes, 2002, p. 59). Information interventions - the presentation of previously unknown facts and data that help people perform in a work or educational environment (Clark & Estes, 2002). Interventions - strategies that help close the gaps in knowledge and skills. Interventions types include information, job-aids, training, and education. Job-aid interventions - a higher level of information that helps people perform tasks on their own, without the assistance of an individual. Recipes for cooking are a common example of job aids (Clark & Estes, 2002). Job-aids can take on a physical shape, as in the design of an object. Scissors and hammers are job-aids, as their shape assists their function intuitively. Performance – the ability to perform a task Training – defined as “any situation where people must acquire “how to” knowledge and skills, and need practice and corrective feedback to help them achieve specific work goals (Clark & Estes, 2002, p. 58.) Training interventions: The transfer of knowledge and skills through guided practice and feedback opportunities (Clark & Estes, 2002). To determine the student’s needs ask yourself these quick questions: Does the student need to gain new information in order to perform a task? If yes, the student needs an information intervention. Does the student have some knowledge or experience about a subject but does not need to have that information memorized in order to perform a task. If yes, the student needs a job-aid intervention. 19 Does the student need to learn new information that is mostly procedural and requires practice? If yes, the student needs a training intervention. Does the student need to be able to problem-solve in the future? If yes, the student needs an education intervention. In most cases, the complexities of the interventions increase as you move from information interventions to education interventions. References Fill in later Clark R. E. & Estes, F. (2002). Turning research into results: a guide to selecting the right performance solutions. Atlanta, GA.: CEP Press 20