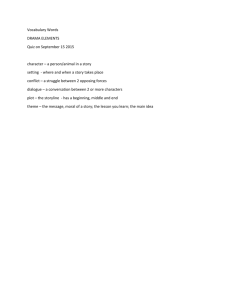

the six elements of fiction

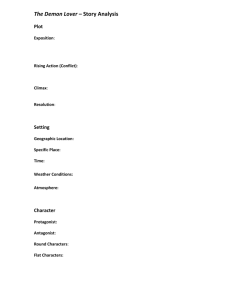

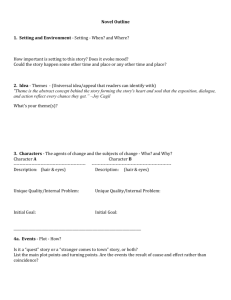

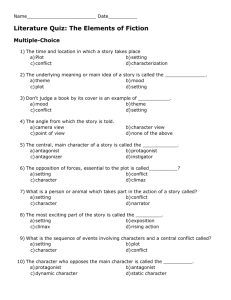

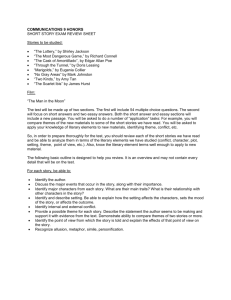

advertisement

THE SIX ELEMENTS OF FICTION PLOT: The arrangement of the incidents that take place in a text’s story. A plot has five parts: an Exposition / Inciting Incident (“kicks off” the story), Rising Action (and then what happens? and then?), a Climax (does the protagonist win or lose?), a Falling Action/Denouement (wrapping up loose ends), and the Resolution / End. Of the five, the Rising Action is the longest part of the plot. CHARACTERS: The personalities or characters that carry out the actions and dialogue of the plot. There are two types of main characters: the protagonist (the principal character that most of the action centers around; sometimes he or she is a hero, but not always!) and an antagonist (the person or thing that stands in the protagonist’s way of achieving his or her goals). The opposition of the protagonist and the antagonist is the main part of the plot’s conflict: the struggle between opposing needs in the story. Characterization is usually revealed by what the character says or does, what the character looks like, what another character says aloud about the character, and/or what the narrator tells or reveals to the reader. SETTING: Where and when does the text happen? Consider both the actual places (a boat in the Pacific Ocean? A spaceship on the way to Mars? A rundown mansion? Denmark?) and the timeframe (2027? The Middle Ages? During the Civil War? Present day?). Some definitions and examples from Oxford Concise Dictionary of Literary Terms by Chris Baldick, 1996, and Perrine’s Literature: Structure, Sound and Sense, Tenth Edition (Arp and Johnson, editors). POINT OF VIEW: The position or vantage point from which the events of the text seem to be observed and presented to us. Who is the narrator of the story? The three most common POVs are: FIRST PERSON: The narrative is in the “I” form. The thoughts and knowledge are limited to this one person. THIRD PERSON LIMITED: The narrative is in the “he/she” form. The thoughts and knowledge are limited to this one person. THIRD PERSON OMNISCIENT: The narrator seems “over” the characters (a “bird’s eye” observation) and has unrestricted knowledge and access to two or more characters’ thoughts and knowledge. Omniscient narrative might combine the traits of First Person and Third Person Limited points of view. TONE / MOOD: The atmosphere of the text. The tone is the writer’s attitude toward the subject matter (ironic, light, satiric, solemn, angry, sentimental, tragic, comedic, etc.). The mood is the emotions the reader feels while reading the text (mysterious, suspenseful, happy, sad, etc.). Often, complicated or longer works will have shifts in tone and mood. THEME: The overall, underlying message/meaning of the text. It is usually implied or suggested -- not directly stated. A theme “oversees” the major events of the text, and should be defendable and provable. It is often a sentence stated in universal or abstract terms, such as “Wisdom often will win over brute force.” Do not confuse theme with a text’s plot (summary of specific story details), topic (“old age”), or subject (“Fighting a marlin in the open sea can test what you’re worth”). Think of a theme as something revealed by the text. A good theme should have the following: 1. It should be a full sentence. “Loyalty to country often inspires heroic selfsacrifice,” NOT “loyalty to country.” Consider your theme the thesis of a major paper, where you’ll “prove” it correct with multiple text examples. 2. It should be a generalization about life. If you mention specific plot points, character or place names, it is NOT theme. 3. Be careful to use words like “always,” “all,” “every” – your text is unlikely to support this! It is better to use words such as “some,” “may,” and “sometimes.” 4. It is a central and unifying concept – if the main characters or major plot points contradict your theme, reconsider it. Does the theme illustrate the journey of the protagonist(s)? 5. Although it can be a “lesson learned,” avoid clichés and overstated “morals,” such as “You can’t judge a book by its cover” or “The early bird gets the worm.” Literature is often more deep than an instructive fable. Go deeper! Some definitions and examples from Oxford Concise Dictionary of Literary Terms by Chris Baldick, 1996, and Perrine’s Literature: Structure, Sound and Sense, Tenth Edition (Arp and Johnson, editors).