Happily Ever After

advertisement

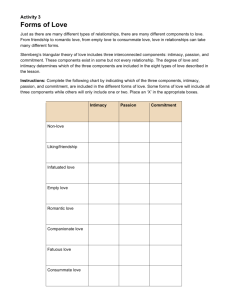

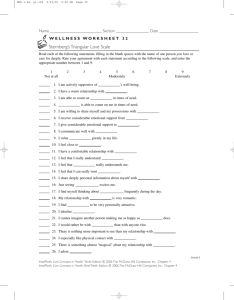

Feraco Myth/Sci-Fi – Period 24 September 2009 Happily Ever After Robert J. Sternberg, Dean, Tufts University School of Arts & Sciences Once upon a time, a story you heard, or a book you read, or a movie you saw taught you what love is. Could it be affecting your relationships? When I was 13, there was a girl I liked, but I was rather shy and didn’t know how to approach her. Then I had a clever idea. I happened to be doing my seventh-grade science project on intelligence testing, and as part of it, I was giving some of my classmates the StanfordBinet IQ Test, which I had found in the town library. I thought that if I gave the test to the object of my affection, I might break the ice and begin a wonderfully romantic relationship. Unsurprisingly, my plan failed. I did, however, become friends with the girl, and 44 years later, we’re still in occasional e-mail contact. We tell each other about our lives, our challenges, and our joys and sorrows, preserving the intimacy that began – despite my bumbling advances – so many years ago. By 16, I believed I had found the woman of my dreams. She was in my tenth-grade Biology Honors class, one row in front of me and two seats to the right. I spent the whole year obsessing over her, trying not to be obvious when I stared at her. I felt intense passion, even though I didn’t really know her at all. Eventually a relationship commenced, but not with me. She got involved with the captain of an athletic team. Later, I was in a relationship that was full of both intimacy and passion – for a while. But then those qualities faded. What was left was commitment, the sense that I really should stay in the relationship. So I stayed for awhile, but the relationship ultimately dissolved anyway. Scientists arrive at their theories by different routes, and my own work in psychology has always arisen from my personal experiences. This was true as far back as that seventh-grade science project: I was studying IQ tests mainly to figure out why I performed so poorly on them. In the case of my research on love, the romantic adventures I’ve just described got me thinking, and in time I’ve come up with a theory to explain why some relationships flourish and others fizzle. I won’t keep you in suspense. My theory is that our culture abounds with different sorts of love stories, and that people unconsciously absorb those stories, letting them shape their expectations of relationships. How well two people do in a relationship depends largely on how compatible their stories are. I call this the theory of love as a story. That, as I said, is the theory I developed in time. On the way, I conceived a more basic theory, one that has less to do with emotional expectations and more to do with emotions themselves. This I call the triangular theory of love. It is based on the idea that love consists of the three components I learned about through those early relationships: intimacy, passion, and commitment. Different combinations and strengths of those three ingredients produce different kinds of love. Taken together, the triangle theory and the story theory can account for much of love’s bewildering variety, not just in type but in quality. Will you recognize your own relationships here? It’s hard to say. But you might at least begin to think about your relationships a little differently. Love Triangles Let us begin, as I did on my quest to understand love, by looking at those three key ingredients I identified – intimacy, passion, and commitment. Intimacy, as I define it, is the feeling of closeness that gives rise to warmth and caring; it’s what allows people to share confidences and give and receive emotional support. The young Harry Potter’s friendships with Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger, for instance, are based purely on intimacy. Passion is all about intensity. You say you can’t imagine life without the other person or can’t get him/her off your mind. Passion often resembles an addiction, and when someone unceremoniously dumps us, we feel withdrawal symptoms, much as we would after kicking caffeine or nicotine. Passion, probably descended into obsession, is the rocket fuel that propelled the astronaut Lisa Nowak halfway across the country in February 2007 to confront her romantic rival with pepper spray. The commitment component of love has to do with our drive to maintain a relationship over the long term. For short-term relationships, there is an analogous component that might be called the decision component, the simple decision to love a certain other person. Commitment is much of what kept Tevye and Golde together in Fiddler on the Roof. It is also what kept many top politicians and their spouses together before it was conceivable that a U.S. presidential candidate could be someone who has experienced a divorce. Sometimes one or more of these components are present in our feelings for a person; sometimes none of them are. Eight different permutations are possible, each giving rise to a distinct type of relationship. Perhaps the easiest to explain is non-love, the absence of all three components. It is the relationship one has with an acquaintance. Another kind of relationship, liking, develops when only the intimacy component is present. We can also feel passion without either of the other two components of love. Infatuated love – all passion, no intimacy or commitment – is what Scarlett O’Hara feels for Ashley Wilkes in Gone With the Wind. And sometimes, in what might be called empty love, the commitment component of love exists despite a lack of intimacy or passion. In our culture, empty love often characterizes a marriage that’s headed for divorce, but in matchmaking cultures, marriages start out with empty love; the matched couple is expected to develop intimacy, and possibly passion, later on. Romantic love, the love between Tristan and Isolde, Romeo and Juliet, Pyramus and Thisbe, and countless successors, is the combustion of intimacy and passion in the absence of commitment. It is common on college campuses, where students fall in love but often feel too young, or too uncertain about the future, to commit to a long-term relationship. Companionate love results when we have only intimacy and commitment, as in a long-term deep friendship. It is what many feel after the passion in their relationship has waned. In the Dr. Zhivago, Yuri is married to Tonya, with whom he shares companionate love. But then he meets Lara, who sparks romantic him. His romantic love for Lara wins out over his companionate for Tonya. couples movie love in love Another possibility is passion and commitment without intimacy. This yields what I call fatuous love, the variety that appears to have beset J. Marshall Smith, the 89-year-old billionaire who married Anna Nicole. Finally, there is what I call consummate love, which includes all three components – intimacy, passion, and commitment. Every “happily ever after” story, like “Cinderella,” describes consummate love. In real life, consummate love, like weight loss, is harder to maintain than to achieve. From what we can tell, Ronald and Nancy Reagan achieved it; Jack and Jackie Kennedy did not. Of course, no relationship is likely to be a pure case of any of the eight types. This is at least partly because the three components of love work together. Commitment may lead to greater intimacy or passion, for example. By the same token, intimacy may lead to greater passion or commitment. The triangle of love can change its size as you feel more love, or it can change its shape as the balance among intimacy, passion, and commitment shifts. And naturally, the importance of any single component may differ from one relationship to another, or over time within a given relationship. If the triangular theory of love is viable, then different types of relationships should show different average balances among the three components. While a professor at Yale University, I set out to test whether that was true. I gave equal numbers of men and women 12 statements, each focusing on one of the three components of love, and asked them to rate each statement from one to nine, depending on how well it described their relationship with a particular person. A statement to gauge intimacy, for instance, would be “I have a warm and comfortable relationship with ________.” To gauge passion: “I cannot imagine another person making me as happy as ________ does.” To gauge commitment: “I view my relationship with __________ as permanent.” Everyone rated all 12 statements for six different relationships – mother, father, sibling closest in age, lover/spouse, best friend, and ideal lover/spouse. The participants were given other scales, too, among them one that measured overall relationship satisfaction. I learned that different relationships do indeed imply different levels of the three components. The passion rather averaged 6.9 for lover/spouse, but only 5.0 for mother. The mean intimacy rating for lover/spouse was 7.6, with best friend of the same sex following closely at 6.8. For commitment, the difference between lover/spouse and the next highest mean, mother, was only 1.1. Higher levels of some components of love were linked with higher levels of others. Intimacy and commitment, for example, were more closely related to each other than either intimacy and passion or passion and commitment. I also found a strong connect between high love-scale ratings and satisfaction with one’s relationship. Couples tended to be happier when they had more of the three components of love. And it helped if their love triangles matched in size and shape – that is, if the amount and kind of love each partner felt for the other was about the same. Love Stories For years, I was satisfied with my triangular theory of love. What got me to probe deeper was the nagging question of how the various triangles of love arise. Just where do they come from? I began to think about what we bring to our relationships, about what lies in our hearts and minds before the first kiss, or even the first hello. That’s how I started developing the theory of love as a story. All of us are exposed to many different stories about love. They reach us through our own experience, as well as through literature, the media, and so forth. Some love stories are self-contained, while others are embedded in larger stories. Either way, they offer multiple conceptions of what love can or should be. I myself have been influenced by the fairy tales I heard when I was young – “Cinderella,” “Sleeping Beauty,” “Rapunzel,” and the like – and by the books I read and the movies I saw in my adolescence, such as Gone With the Wind, Rebecca, Jane Eyre, Anna Karenina, Wuthering Heights, Dr. Zhivago, and Casablanca. Under the spell of the stories we absorb, we gradually form our own personal stories about love – models of how love is “supposed” to work. How we develop our own stories and what they turn out to be depends on our personality and our environment, but once we have a story – or, like many of us, a set of stories – we seek to live it out in reality. That’s the theory. And it’s a theory for which I found some support in psychological literature, including the work of the late Dorothy Tennov. A psychologist who devoted much of her career to the study of romantic love, Tennov observed that people differ in their tendency to fall in love. She showed that people who are more susceptible to romantic love are more likely to prefer romantic stories, and vice versa. But I wanted to develop the role of stories further. I was thinking about how, as we wend our way through life, we meet potential partners who fit our stories to greater or lesser degrees. It seemed reasonable to suppose that people are more likely to succeed in a relationship with a partner whose story closely matches their own. But I had no evidence, so, while at Yale, I set out to test my theory. I started poring through literature, films, and oral histories to get a clearer sense of what the love stories in our cultures actually are. It didn’t take long to discover that certain types of stories tend to dominate Americans’ conceptions of love (see “Stories We Live By”). There’s love as a cookbook, for example, where lovers build a relationship by following a “recipe,” or love as a fantasy, complete with knight in shining armor, or love as a game or sport – 26 stories in all. After I identified these basic stories, my colleagues Mahzad Hojjat and Michael Barnes and I tried to determine how they affect people’s lives. At first, we asked people to identify the stories that applied to them. But they generally were unable to – most were not even aware they had such stories. It was clear we would have to devise a questionnaire to draw people out. Accordingly, we had couples rate the extent to which various statements characterized them and their relationships. Each statement was keyed to one of the 26 basic love stories, and the idea was that participants’ rating would tell us something about what their own personal love stories were. For instance, the statement “If my partner were to leave me, my life would be completely empty” would be rated highly by someone with an addiction story (in which couples cling to one another), while someone with a garden story (in which love is a thing to be nurtured) would favor the statement “I believe a good relationship is attainable only if you are willing to spend the time and energy to care for it, just as you need to care for a garden.” For someone with a history story (in which couples seek to put their love in a historical context), the statement “It is very important to me to keep objects or pictures that remind me of special moments that I have shared with my partner in the past” would strike a chord, while “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with having your partner be slightly scared of you” was designed to tease out people with a horror story (in which terror is what makes a relationship interesting). Again, the participants were also given other scales, including the one for overall relationship satisfaction. The first thing we noticed was that some stories were a lot more popular. The most common were travel, gardening, democratic government, and history, in that order. The least common were horror, collection, autocratic government, and game. There were sex differences as well: more men than women gravitated toward art, degradation, sacrifice, and science fiction, while women favored travel. We also noticed that certain love stories went hand in hand: people who saw love as a horror story also tended to see love as a war story. What you really want to know, of course, is, Which are the magic stories that lead to happiness? And I wish I could tell you. The fact is, none of the stories in our study were strongly correlated with relationship satisfaction. We did, however, identify stories that don’t work well. Here are some that were strongly tied to a lack of satisfaction: business, collection, game, government, horror, humor, mystery, police, recovery, science fiction, and theater. We also discovered that people’s lack of awareness about their personal love stories is often fairly profound. Not only did most participants in our story fail to grasp that they were acting out stories, but they believed they were carrying around a set of rocksolid facts about what love is or should be. Some deemed themselves or their partners inadequate for not measuring up to the supposed standards that the stories establish. Indeed, we found that abstract standards often had a greater effect on a relationship than real people did. When it came to predicting satisfaction in a relationship, for example, how people saw their partner carried less weight than how much difference they saw between their partner and their ideal partner. The greater the difference between the real and the ideal, the less satisfaction they experienced. Moreover, how Person A really felt about Person B bore no correlation at all to Person B’s satisfaction in the relationship. What mattered was Person B’s story about how Person A felt. Finally, our research did support my key premise: that partners with similar love stories are more likely to have a satisfying relationship – just as people with similar love triangles are. The stories needn’t be identical; complementary stories can work nicely, too. Travel and garden stories, for example, both involve projects that people jointly pursue over time. Conversely, the more different a couple’s stories are, the less satisfied they tend to be with their relationship. Perhaps you can see how stories, powerful as they are, can shape the three components of love in my triangular theory. You might expect, for example, that the house and home story, where the focus in on the upkeep of a domicile over time, would be linked to high levels of commitment – and that is exactly what we found. Likewise, passionfilled stories such as fantasy tend to produce high passion ratings on the triangular love scale. What’s Your Story? By now you might be curious to learn which triangles and love stories operate in your own life. I have a few suggestions about where to begin; you can fill out versions of the questionnaires we gave participants in our stories, for example, at go.tufts.edu/lovequest. The alternative – which is easier said than done – is to try to be sensitive to the kinds of things that matter to you and your loved one. A partner who tells you lots of details about his or her thoughts and feelings is probably big on intimacy. One who surprises you with gifts may be into passion. If you partner values commitment, he or she will always be there for you, regardless of circumstances. Someone who treats you like a prince or princess may have a fantasy story. If your partner is inordinately concerned about your finances, you may be in a business story. If your partner always seems to be keeping score, there’s a game story going on. And if you are under constant surveillance, watch out: you may the suspect in a police story. If you’re not happy with what you find, don’t lose heart. Stories of love can and do change with life experience. As people spend more time together, their stories may gradually converge. Couples may even discover that, whatever their stories were before, they are writing a new one of their own.