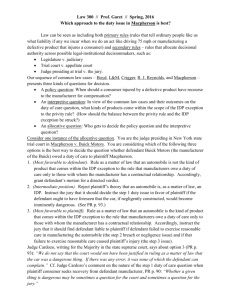

BLT/4e CP 7-10

advertisement