Title: “Go Down, Moses and Intruder in the Dust: from negative to

advertisement

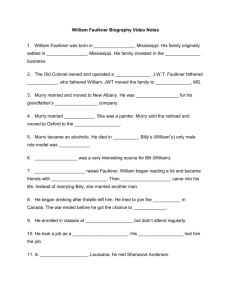

Title: “Go Down, Moses and Intruder in the Dust: from negative to positive liberty” Author(s): Carl J. Dimitri Source: The Faulkner Journal. 19.1 (Fall 2003): p11. From Literature Resource Center. Document Type: Critical essay Bookmark: Bookmark this Document Full Text: Various attempts have been made to categorize the general stages in Faulkner's career. Michael Millgate was the first to relegate Faulkner's poetry and first three novels to a "period of apprenticeship." The great or major period that stretched from 1929 to 1936 was succeeded by a "middle period" which drew to a close in 1942. And finally the "late period" that surfaced after World War II began with Intruder in the Dust (1948) and concluded with The Reivers (1962) (102). Other commentators, such as Joseph Gold, have been satisfied with the division of Faulkner's corpus into "two phases, two bodies of work, roughly divided by World War II" (4). Bearing this out, critics such as Judith Wittenberg and Daniel Singal view Go Down, Moses (1942) as one of Faulkner's masterworks, and as the final work of his first or great phase. But they also see it as a work of transition which employs techniques that are characteristic of the later years: an example of which is that it contains the tendency to theorize about social issues--as in the latter part of the "The Bear"--instead of displaying them dramatically (Wittenberg 190, Singal 256). With the exception of the five short stories published after Go Down, Moses, Faulkner remained artistically silent for six years. By contrast with the thirteen novels and two volumes of short stories published between 1926 and 1942, the decline in his productivity, at least, was drastic. For Millgate, when Faulkner did reappear onto the literary scene with Intruder in the Dust, it was with a "polemical tone" that "plainly marked a new development" in his work (84). Critics generally agree that the later period is characterized by a new-found penchant for exposition, by the ascendancy of the tedious Gavin Stevens (a central figure in five of the final seven novel-length works), by the apparent need to make direct statements on social and political issues, and by the explicit explication of moral alternatives. For Gold, these developments point to Faulkner's move from "the making of myth," which conveys complex meaning through association, suggestion, and images, to the "construction of allegory," which delivers a fixed meaning through the presentation of "disguised ideas" (16). The "increased element of ideation," Wittenberg writes, gives way to the construction of characters who "more obviously represent moral, political, and philosophical stances than they did in the earlier works, where they were, above all, complex individuals struggling to survive" (205). According to Louis Brodsky, these developments are all the more curious since the younger author sought "to avoid preaching at all costs in his writing as well as in social discourse" (88). In the most general terms, Faulkner's 'shift' from his early to late period is characterized by a turn from a modernist aesthetic to an aesthetic of engagement. During his "period of apprenticeship," he prioritized form and style in his poetry and novels to an extent that antagonized socially-minded critics of the day. Under the influence of romantic, fin de siecle, decadent, and symbolist poetry, the young author identified with a lyrical, aesthetically-oriented tradition. And as a member of the post-WWI generation, he strove to detach himself from mainstream mores and literary conventions. The emphasis on the world of nymphs and fauns, on arcadian gardens and on the notion of a transcendent Beauty (as in Soldiers' Pay), belongs to the attempt to retreat from society and into an aesthetic sphere of experience (Honnighausen 47). Similarly, his major works in general are grounded on the qualities and principles of European high modernism. Quentin, Darl, Popeye, Benbow, Temple, Hightower, Joe Christmas, and Henry Sutpen can be identified as the modernist "decentered" or psychologically troubled subject who is assailed from within by unconscious forces, and by a hostile ever-changing modern world from without. Faulkner demonstrates the way in which "the everyday life of commercial society is forced to reveal its darker, nocturnal side as the self is unraveled through tropes of intoxication, violence and perversity" (Nicholls 42). Employing a poetic and imagistic prose, Faulkner tended to concentrate on the chaos within the individual consciousness, and the way in which it often functioned as a reflection and symptom of the external world. The emphasis on the irrational served to reveal what is repressed and repelled, and the alienation from the decadence of an instrumental civilization. At times, he also upheld irrational and primitivistic modes of life as methods of emancipation from an increasingly mechanized and "demystified" world, while consistently reminding us that neither lasting emancipation nor redemption were possible in the world represented. Hopes for reconciliation between characters, or between his artwork and his society, were dashed as he generally created uncommerical, abstruse, and at times, shocking works of art. The idea of a fixed, stable truth and that of an inherently meaningful universe were repudiated and supplanted by a contingent, fragmented world often presented through multiple, decentered perspectives. Of course, at the same time, it can be said that through this emphasis on the chaotic and ephemeral, Faulkner was revealing his desire for an undefiled and meaningful life. Much of Faulkner's earlier work repudiates and is detached from what is normative; it identifies with the modernistic "Great Refusal--the protest against that which is" (Marcuse 61). The characteristics of detachment and refusal have their correlative in the politically 'disengaged' aspects of the work. This is not to say that they are asocial or even apolitical. Inherent in the critique of modernity and in the adversarial stance toward society is a harsh commentary on public life. Representations of discord between the races, and of the hysteria over the issue of miscegenation, for instance, disclose the reality of racial prejudice, injustice, and inequality. Faulkner displays the need for justice and equality powerfully by stressing their absence. Further, the critic can always spot "the existence of a repressed social content even in those modern works that seem most innocent of it" (Jameson 202). It is always possible to 'read' early Faulkner politically, to recognize and foreground what was implied or even unintended by examining the unconscious or latent meanings hidden in signs and symbols. But it is also the case that this political content is submerged or secluded "out of sight from the very form itself, by means of specific techniques of framing and displacement" (Morris and Morris 11). There is, in other words, a clear distinction between works which contain an unconscious or an implied political content, and those which confront social-political issues in a way that ordinary readers, and not only trained critics, are able to recognize. The point here is that the younger author "did not see his fiction as a weapon in the ideological struggles of the day, as many other writers of the era did" (Brinkmeyer 81). In the early phases of his career, the end of the artistic endeavor was, above all, the production of a formally- and an aesthetically-refined work of art. Social and political issues were always subordinate to this end, just as content was ultimately always subordinate to form. But Faulkner did not suddenly begin to engage directly with social and political issues with Intruder in the Dust; rather, he moved over time toward such a stance in response to specific historical circumstances. Initially, the relation he made between his work and politics was actually external to the work. In 1938, he donated the typescript of Absalom, Absalom! to a fund benefiting the loyalists of the Spanish Civil War. In doing so, he sent a signed statement to the League of American Writers: "I most sincerely wish to go on record as being unalterably opposed to Franco and fascism, to all violations of the legal government and outrages against the people of Republican Spain" (Blotner 1030). Faulkner attempted several times to join the military of WWII, but to his frustration he was consistently rejected. Following these efforts he came to formulate a civilian and artistic role for himself in regard to public causes. In a letter of 1942 to his stepson Malcolm Franklin, he first stated, although privately, his intention to commit himself and his writing to such causes. After "liberty" and "freedom" are secured by the military, he writes, Then perhaps the time of the older men will come, the ones like me who are articulate in the national voice, who are too old to be soldiers, but are old enough and have been vocal long enough to be listened to, yet are not so old that we too have become another batch of decrepit old men looking stubbornly backward at a point 25 or 50 years in the past. (SL 166) As far as the actual work is concerned, two of the short stories of the early forties are the first to confront directly the issues of freedom and oppression, resistance and sacrifice-issues that preoccupy Faulkner throughout the later period. "Two Soldiers" and "Shall not Perish" tell the story of a young farmer who makes a decision to enlist in the army, of his death, and of his family's struggle to come to terms with that loss. Through the character of Mrs. Grier, the soldier's mother, Faulkner espouses a belief in the need for commitment against tyranny. Significantly, his "national voice" is already becoming audible as Mrs. Grier convinces Major de Spain, who has also lost a son, that the struggle for freedom has to continue at all costs: "'All men are capable of shame,' Mother said. 'Just as all men are capable of courage and honor and sacrifice. And grief too. It will take time, but they will learn it. It will take more grief than yours and mine, and there will be more. But it will be enough'" (CS 108). Faulkner never developed a consistent conception of "political commitment" or authorial responsibility, nor did he always advise young writers to commit themselves or their work to public issues. Yet, he was much more inclined after WWII to sanction an aesthetic of engagement. In 1931, an interviewer gathered from his comments that "No, he had nothing definite to say in his work--no special program. He usually begins with a character and just starts writing" (LG 17). But speaking in Manila in 1955, Faulkner remarks that the writer has a simple obligation to his craft and to "tell the truth in such a way that it will be memorable, that people will read it, will remember it because it was told in some memorable way" (LG 201). He then raises the charge: the writer "must have absolute integrity; he must have a sense of responsibility; ... he must believe that man will continue to endure and prevail" (LG 200). Later, he stated that the writer's "job" was "to remind people that people must be braver than they were, that they must be more generous, that they must have compassion.... he must remind the people who are in command and in charge of [the American] economy, our culture of success, that there is more to being a member of the family of man than just success" (LG 212). In 1958, he declared that the young writer's duty is to "save mankind from being desouled as the stallion or boar or bull is gelded; to save the individual from anonymity before it is too late and humanity has vanished before the animal called man" (ESPL 165). And in one interview he goes as far as to announce that the artist communicates "man's most supreme expression," and that art "is also the salvation of mankind" (LG 71). As opposed to the earlier tendencies toward detachment and refusal, the mature author expresses the belief that "man ought to do more than just repudiate" (LG 225). His pledge of allegiance to this new aesthetic, and to the concept of authorial responsibility, finds its most famous and public expression in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, where Faulkner claims "this moment as a pinnacle from which" he "might be listened to by young men and women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail" (ESPL 119). A comparison of Go Down, Moses and Intruder in the Dust makes evident the change in Faulkner's understanding of the role of the writer, particularly when we examine the differing approaches to, and uses of, the concept of liberty. In Go Down, Moses, the issue of liberty is an important motif; in contrast to Intruder in the Dust, however, discussions of the overtly political aspects of liberty are more or less absent. Roth Edmonds introduces the topic of WWII while worrying that Fascism could gain a foothold in America. But Isaac McCaslin quickly puts his fears to rest, asserting almost chauvinistically that in time the country will meet the challenges posed by Hitler, or "one Austrian paper-hanger, no matter what he will be calling himself " (GDM 323). The younger Faulkner addresses the notion of liberty within a social context. In "The Bear," for instance, he writes of the mythic but fading wilderness, contrasting the freedom and purity inherent in the virgin land with the limitations and decadence of civilization (Backman 165). In terms of race, the South is alluded to as the modern version of ancient Egypt, while black people are likened to the captive Israelites. Blacks are enslaved and oppressed by whites, and, in turn, whites are forever burdened with the shame and guilt of slavery. Freedom does not seem possible in this earlier novel, and all struggles for it appear hopelessly naive and futile. In "The Bear" he depicts the plight of a black couple struggling to create for themselves a life free of white paternalism and racism. Fonsiba, a black McCaslin, moves with her Northerner husband to an uncultivated farm in Arkansas. Upon delivering Fonsiba's inheritance money, Isaac finds that both she and her husband stand on the brink of starvation, and that they refuse to renounce their decisions, the actions they have taken, and the belief that they are capable of independence. The emaciated Fonsiba says, "'I'm free,'" but not without a fair amount of self-deception. And although her husband speaks of "freedom, liberty and equality for all" his words, Faulkner writes, resound with the "sonorous imbecility of the boundless folly and the baseless hope." The predicament is such that Isaac concludes that "no man is ever free and probably could not bear it if he were" (GDM 266-69). Still Isaac takes up his own quest for a particular type of freedom, one which parallels his passage into manhood. Under the tutelage of Sam Fathers, the Chickasaw with African blood, he gains an understanding of the woods, of nature, and of the virtues of manhood. He encounters mythical bucks and bears and finds that the ultimate meanings of life are revealed in and through nature. Confronting the bear and his fears without a gun teaches him to become a hunter in the Chickasaw tradition, as well as a man of wisdom, courage, and honor (GDM 198). Upon reaching manhood, and embarking on a different kind of hunt, Isaac studies the McCaslin ledgers and discovers the sins hidden in the family tree: Old Carothers McCaslin had not only owned and seduced slave women; he had also molested his own daughter, the daughter of his "affair" with the slave Eunice. And when Carothers impregnates the daughter herself, he dismisses the child--along with all guilt and responsibility--with a payoff of 1,000 dollars. Isaac repudiates his heritage based on land and slave ownership, and argues with Cass Edmondsthat neither man nor wilderness was intended to be owned, since nature was God's gift to humankind, and that all that He asked in return was a human existence of brotherhood and virtue, not slavery and rapacity. With this repudiation, Isaac chooses to withdraw into himself and away from this world of corruption, securing, it seems, the only type of liberty possible. "Negative liberty," Isaiah Berlin suggests, consists of freedom from external interference. Liberal and libertarian thinkers have shown that such liberty depends upon the preservation of a certain amount of freedom which cannot be infiltrated by external forces (132). The individual's quest for negative liberty has historically taken the route of what Berlin calls "self-abnegation"--a method traditionally used by stoics, ascetics, and quietists in the effort to emancipate the self from the world and worldly desires. Selfabnegation consists of the retreat into the self when the "external world has proved exceptionally arid, cruel or unjust" (132). In this way, Isaac works to escape a society fraught with racism, greed, and lust by retreating into himself, renouncing his claim to the McCaslin inheritance, adopting ascetic life principles, refusing the money and land, and allowing his marriage to dissolve. The ultimate end of Ike's protest is to secure his own negative liberty. His repudiation itself is enacted in the hope that it will confer upon him a certain amount of freedom from the corruption haunting his family and community. Debating with Cass, the head of the family, he says "'I'm trying to explain ... I could say I dont know why I must do it but that I do know I have got to because I have got myself to have to live with for the rest of my life and all I want is peace to do it in'" (GDM 275). Initially, Ike does seem to secure an amount of peace and freedom from "the world" and, to a degree, he is commended by Faulkner for rejecting "the old wrong and shame" of slavery, incest, and greed; at the same time, though, Faulkner suggests that the method employed only ensured that he "couldn't cure the wrong and eradicate the shame" (GDM 334). As Olga Vickery and a host of other critics have suggested (a point I can only support and use as support for the larger aim of this essay), Ike ultimately retreats into the wilderness, where he becomes a childless and wifeless stoic who has ceased to recognize and empathize with human experience and emotion. In "Delta Autumn," Faulkner juxtaposes Ike's increasing futility as a social being and sage with images of the waning wilderness. In a discussion concerning the decline of the woods and of the life within it, Roth accuses his Uncle Ike of believing that the character of men has also declined. In an effort to defend himself, Ike suggests that modern circumstances keep men from the heroism and nobility of the past. To this Roth returns, "So you've lived almost eighty years.... And that's what you finally learned about the other animals you lived among. I suppose the question to ask you is, where have you been all the time you were dead?" (GDM 329). Roth provides a poignant insight into Ike's fate, for the freedom Ike has attained has left him essentially "dead to the world." This becomes clear when he meets the woman Roth impregnates and abandons, realizing that she is a mulatto descendent of the McCaslin clan, and that the cycle of sin and shame has never stopped spinning. Faced with the opportunity to confront and engage with the family curse of incest and betrayal, Ike panics and recoils from it. The ordinarily tranquil sage loses his composure, and he thinks: "Maybe in a thousand or two thousand years in America.... But not now! Not now!" (GDM 344). Unsettled by the reccurrence of miscegenation, Ike abandons the Christian ethic of a universal brotherhood. As Daniel Hoffman points out, whereas the mixed blood of Sam Fathers, Lion, and Ike's fyce is intimately associated with their courage and sense of honor, Ike's fear of miscegenation exposes a weakness in his thinking, a failure to transcend longstanding and refractory prejudices (170). Not only is Isaac frightened into impotence before the ghosts of his past, but he ultimately devitalizes his original protest. His retreat into the wilderness, into an inner world, in the name of virtue and humanity, breaks the bonds between himself and his community so that, as a consequence, he has lost his understanding of both virtue and all that is common to human experience. Ike tells the woman to move away, marry someone of her own race: "you could find a black man who would see in you what it was you saw in [Roth], who would ask nothing of you and expect less and get even still less than that, if it's revenge you want." Her response, though, shows that he has misread her values and motives, and that the ideals he had once held dear have now become alien to him: "Old man," she says, "have you lived so long and forgotten so much that you dont remember anything you ever knew or felt or even heard about love?" (GDM 346). Like Isaac, Chick Mallison of Intruder in the Dust also experiences a passage into manhood which is bound up with an idea and pursuit of freedom (Vickery 132). Here again the white adolescent's initiation is intimately linked to the hunt and to a relationship with a man of mixed blood, namely, Lucas Beauchamp. While hunting rabbits on Roth's land, Chick falls into an icy creek. Lucas appears, directs the boys to retrieve Chick, and leads him home. Chick, then, undergoes a baptism into a new understanding. It is the moment in which he first confronts the aberrant Lucas and the narrow cultural assumptions that he has taken as his own. Chick's expectations are initially satisfied at Lucas and Molly's house. The odor, food, and interior of the home appear to suggest an essentially Negroid nature. But with relative quickness Chick begins to question his assumptions, wondering if such sights, smells, and sounds are bound up not with an essential nature but with the processes of historical and social conditioning. perhaps that smell was not really the odor of a race nor even actually of poverty but perhaps of a condition: an idea: a belief: an acceptance, a passive acceptance by them themselves of the idea that being Negroes they were not supposed to have facilities to wash properly or often or even to wash bathe often even without the facilities to do it with; that in fact it was a little to be preferred that they did not. (ID 11) In his determination to defy social roles that are both fixed and oppressive, Lucas helps Chick abandon ignorance and prejudice for a less tendentious understanding of what is seen as the "Negro." There is something that "looked out ... from the man's face" that causes Chick to doubt himself. Lucas's inner strength and sense of dignity helps Chick realize his "initial error, misjudgment" concerning what black people are and what they should be (ID 14). Faulkner makes a sincere attempt at challenging cultural stereotypes here, a sincere attempt at positioning Lucas as a representative of independent thought and action, an individual intellectually and morally free of white authority. Various critics, however, find this attempt to be almost irredeemably flawed. Although Lucas strives for freedom from subservience and dependency on white authority, Thadious Davis suggests that he nonetheless finds the source of his own authority in white, patriarchal structures (243). Similarly, Myra Jehlen argues that Lucas is proud not of being black, but of his white ancestry (125). When confronting Zack Edmonds in "The Fire and the Hearth," Lucas shows his pride in being a "man-made" McCaslin (GDM 52). And in Intruder, he almost gets himself killed by flaunting his lineage before a white farmer: "I dont belong to these new folks," he says. "I belongs to the old lot. I'm a McCaslin" (ID 19). In a way that indicates Faulkner's critical limitations, his inability to depict a more "progressive" and organic mode of social behavior for black people, Lucas behaves in the one manner that is deemed admirable: as a Southern gentleman, proud and dignified and self-reliant. In itself this shows that Faulkner was unable to envision a form of social behavior for black people that was independent of white norms and expectations. Yet, it is also the case that Faulkner made an attempt to endow a black character with a muscular drive for autonomy and a substantial amount of self-respect: in Intruder, Lucas's insistence on paying Stevens for his services signals these qualities. And again, in "The Bear," where Lucas changes his name from Lucius, Faulkner writes that he was not "declining the name itself, because he had used three quarters of it; but simply taking the name and changing, altering it, making it no longer the white man's but his own, by himself composed, himself selfprogenitive and nominate, by himself ancestored" (GDM 269). More than most of Faulkner's white characters, Lucas has the capacity for self-government and, perhaps more importantly, self-creation. He creates his own distinct identity, serves his own personal authority. In Intruder, Faulkner ensures that Lucas's behavior and his convictions remain peculiar and "subversive" enough to cause the town's white citizens a considerable amount of anxiety. Lucas has a subtle and powerful way of upsetting the entire order of things, to the extent that Chick, along with other whites, grows preoccupied with fixing him to manageable social roles: "We got to make him be a nigger first. He's got to admit he's a nigger. Then maybe we will accept him as he seems to intend to be accepted" (ID 18). Resisting all such designations, Lucas refuses to forfeit his dignity, and to address white people by "mister" and "miss" and mean it. Lucas, then, is a mystery, a social anomaly, and as a result, he is feared by some and hated by others. For this reason many of the townspeople are relieved to hear that Lucas shot a white man in the back, for this is an act of cowardice and final proof that he is a "nigger" and not the "man" that he claims. In the meantime, Chick tries to play the white patriarch in the Beauchamp home, fails, and wrestles with the resulting frustration. After Lucas warms and feeds him, Chick holds out the sum of seventy cents. Lucas is offended and refuses to acknowledge the coins or tilt "his face downwards to look at what was on his palm" (ID 15). A battle of wills follows. Chick drops the coins and Lucas orders Alec Sanders and Joe Edmonds to return them. Chick, then, struggling to save himself from being indebted to black people (whom he sees as his dependents), sends Molly a dress. But Lucas trumps these efforts by having a "white boy" deliver a gallon of molasses to Chick's family on the humble mule--the animal so often associated with blacks (ID 23). Chick is defeated and begins to see that Lucas is as much of a man, and a Southern gentleman, as the men in his own family. He begins to question the prevailing social codes and rituals, and adopts a new perspective from which he views Lucas and black-white relations. An equally important moment in Chick's "education" occurs after the murder of Vinson Gowrie. Lucas asks Chick to travel to Beat Four and unearth Gowrie's grave. The two figures face each other through the bars of the jail: "looking down [Chick] saw his own hands holding to two of the bars, the two pairs of hands, the black and the white ones, grasping the bars while they faced one another above them" (ID 67). This image--a considerable one--suggests that both races are somehow unfree, both enslaved to a condition devoid of brotherhood and justice. As in Go Down, Moses, Faulkner again indicates that black people suffer from a very literal oppression, one both physical and material, while, as a consequence, the white (or the conscientious one) is jailed by his own guilt, shame, and spiritual unease. These encounters and trials prick Chick's consciousness, provide him with important critical faculties, and finally compel him to act against what he now recognizes as injustice. For Berlin, "positive liberty" consists in the ability to govern or direct oneself, to lead the kind of life or perform the kind of actions that are self-prescribed. "Self-realization," a key form of positive liberty, emphasizes the understanding and mastering of the self and world (131,143). This understanding of things is accompanied by the performance of actions that accord with what has been learned; that is, the subject comes to know why he ought to act in certain ways and then does so. It is in this way, after his "education" or his passage into manhood, that Chick decides to act in a manner that he deems right--a decision that involves rejecting the advice and demands of his family, who are initially convinced of Lucas's guilt, not to take any risks on Lucas's behalf. Chick then moves against the values of both his family and the white community, ultimately transgressing the community's sacred laws by disinterring a grave that "'had been consecrated and prayed into'" (ID 79). Stevens tells Chick to accept the evidence that Lucas murdered a white man; if Lucas is lucky enough, he will plead guilty to manslaughter and die quietly in prison. But with the help of Alec Sander and Miss Habersham, Chick exhumes the grave, finds an alien body in the coffin, and succeeds in re-opening the investigation and proving Lucas's innocence. In short, it is precisely because of Chick's decision to choose the course of positive liberty (or to act according to rational principles rather than retreat before irrationality) that Lucas is saved from a death by fire and lynching. Thus the crucial difference between Isaac and Chick now becomes clear: Isaac struggles for a freedom from the world, while Chick seeks the freedom to act within it. Ike seeks freedom from the sin and shame of the past, while Chick chooses to act against the injustice and racism of the present. Chick's liberty is bound up with the engagement in social crises, with an emphasis on the mastery of the self and world, all of which point toward individual and social progress. In contrast, Isaac chooses to withdraw from society in the effort to secure a minimum amount of negative liberty, never to enlarge the area of public freedom. With Miss Habersham, Alec Sander, and Chick, Faulkner points to the virtues of engagement, and reveals his own notion of the "good community" as one willing to take direct action for a worthy cause. Olga Vickery writes that Alec and Miss Habersham are exceptions to their race and class, that they defy Jefferson's codes of behavior and gamble with their safety in order to secure "truth and justice" (139). The mainstream of the white community is convinced of Lucas's guilt without the support of hard evidence, while the black community has chosen to retreat from the fury of the white mob. Alec at first expresses the frustration of many blacks, seeing that "'It's the ones like Lucas makes trouble for everybody.'" Desperate for help, Chick answers: "'Then maybe you better go to the office and sit with Uncle Gavin instead of coming with me'" (ID 84). Ultimately, Alec rejects fear and Stevens's passivity and chooses to join Chick, even at the risk of his own lynching. As a kind of veteran rebel, or as a woman who had long ago stepped away from the town's prejudices and assumptions, Miss Habersham stands as an inspiration to Alec and Chick. She and Molly had lived "like sisters, like twins," she "had stood up in the Negro church as godmother to Molly's first child," and is now determined to work for Lucas's sake (ID 86). A wealthy descendant of Doc Habersham, one of Jefferson's founding fathers, she is something of an aristocrat. She drives the boys to the graveyard while wearing her white gloves and gold jewelry, helps uncover the grave and, later, sits before Lucas's jail in defiance of the mob. Although Miss Habersham is of the upper class, her desire to help Lucas stems less from a sense of noblesse oblige than from a sense of "familial" duty to Molly and Lucas. It is significant that this group is made up of women, blacks, and children. Miss Habersham takes it for granted that white men are incapable of helping their cause, stating simply that Lucas would not ask Stevens for help because he is a "Negro" and the latter is "a man": "'Lucas knew it would take a child," she says, "or an old woman like me: someone not concerned with probability, with evidence. Men like your uncle and Mr Hampton have had to be men too long, busy too long'" (ID 88). Being a man, or being busy "too long," implies that white men are preoccupied with maintaining power and order: lawyers and sheriffs have been dealing with law and order, and with "probability" and "evidence," for so long that "truth and justice" have become secondary considerations. Chick remembers the corroborative saying of a black man: "If you got something outside the common run that's got to be done and cant wait, dont waste your time on the menfolks; they works on what your uncle calls the rules and the cases. Get the womens and the children at it; they work on the circumstances" (ID 110-11). This view, echoed throughout the novel, holds that minorities are apt to think and act differently--and that they are more likely to focus on the logical surroundings of an event rather than on assumptions derived from a legalistic obedience to facts. If the "common run" implies the established order or the mainstream concerns of the community, then it would follow that white men--or the powerholders--are apparently capable of only working within and affirming the rules established by a thoroughly racist order. In having those who are alienated from such circles of power act in accordance with their understanding of things, Faulkner is actually calling for action that contradicts and circumvents that order. Stevens, a chief figure of the "common run," is often denigrated in Intruder in the Dust as a man of words and theories who is more or less impotent in the face of social crises. In an important symbolic gesture, Chick ceases to listen to the adults in his family and shuts "the door upon the significantless speciosity of his uncle's voice" (ID 80). One of Chick's challenges in his passage to manhood and in his fight for liberty is to escape the immobilizing effect of Stevens's lectures. Chick craves action while Stevens indulges in unbounded arguments that serve to avoid or prevent action altogether. Stevens's "naive and childlike rationalising" makes possible a retreat into himself--a closed sphere where, like Isaac, he secures a minimal amount of freedom from the world's burdens (ID 120). Although Faulkner mocks Stevens to a certain extent, and insisted that he was not his mouthpiece but the representation of a typical Southern liberal, Stevens clearly echoes many of the author's recorded sentiments. (1) Like Faulkner, Stevens suggests that natural rights are valid for blacks and whites alike. The "'economic and political and cultural privileges which are his right,'" Stevens says, need to be given to blacks, while whites need to teach themselves the blacks' "'capacity to wait and endure and survive'" (ID 153). Like Faulkner, Stevens also takes up a paternalistic view of black-white relations. There is apparently no question in Stevens's mind that middle- and upper-class whites are best suited to educate the black--"Sambo," as he puts it--on the proper way to conduct the struggle for equality (ID 152). Stevens espouses the notorious "go-slow" approach to integration that Faulkner speaks of in his non-fiction. The right to vote, legal justice, equal education, and economic opportunities must be won for the black community. But the amount of time needed to achieve these goals is never clear. Stevens tells Chick that equality will one day come, but that "'it wont be next Tuesday'" (ID 152). Although this "moderate" stance seeks to accommodate all parties and prevent violence, it prioritizes the rights of the entrenched white community and the racist state over all else. It is a testimony to the confused nature of Faulkner's stance on civil rights, as well as to the confused nature of Intruder in the Dust itself, that Stevens contradicts these sentiments eighty-five pages later. In the whirlwind of ideas and rhetoric in which he is allowed to indulge, Stevens attacks the prioritization of one race's or one man's liberty over another. we are willing to sell liberty short at any tawdry price for the sake of what we call our own which is a constitutional statutory license to pursue each his private postulate of happiness and contentment regardless of grief and cost even to the crucifixion of someone whose nose or pigment we dont like and even these can be coped with provided that few of others who believe that a human life is valuable simply because it has a right to keep on breathing no matter what pigment its lungs distend or nose inhales the air and are willing to defend that right at any price.... (ID 237-38) The increasingly interventionist activities of Washington--after Truman in 1946 established a presidential committee to deal specifically with civil rights issues--served as an example of the impingement of outside forces upon the liberty of the individual and upon the so-called people's sovereignty. Faulkner was responding to this, but also to the rise of the Dixiecrat party which was adamantly opposed to civil rights legislation, and which was highly popular among white Mississippians. In short, Faulkner labored to walk a diplomatic tightrope. But in this effort for diplomacy and to provide an explanation for his moderate program, he succeeded in transforming the novel into a work of propaganda. Faulkner had once accused Richard Wright of rejecting his role as a writer, and the objectivity which he saw as necessary to it, in order to become a Negro writer. But it can be said in the same way that in Intruder Faulkner ceased to be a novelist and, in the final pages at least, became an apologist for the views of white Southern moderates. In this respect, Intruder in the Dust is ultimately the product of Faulkner's attempt to state his political case in a reasonable and egalitarian-minded manner, and failing. Like the non-fiction, Intruder reveals the author's struggle to overcome the conflict of values taking place within both himself and the region. For Myra Jehlen, Chick is "a Tory who never doubts the right of his class to rule" (129). This point may be true insofar as Chick, in accordance with the principle of noblesse oblige, sees that those of his class and race must take responsibility for the welfare of society. He holds no illusions that blacks and whites belong to the same class or social group, and appears to have no interest in revolutionizing the existing order. On the other hand, Chick does attempt to dismantle the ideological order of his community. He confronts ingrained notions, which tend to take on the character of myth about the intellectual, moral, and spiritual lives of black people. He gains the understanding that his heritage and environment have formed his "passions and aspirations and beliefs," shaping him "into not just a man but a specific man" (ID 148). It is imperative to Chick's growth that he develop a critical consciousness, and it is in virtue of this consciousness that he questions particular codes and rebels against them. Jehlen also suggests that Faulkner sees the white upper class as composed of inherently good and conscientious citizens "eager to do the right thing" (130). This too may be true insofar as Faulkner points to the "aristocrats" of the community (the Habershams, Mallisons, and Stevens) as being better mannered, less violent, and more virtuous than the poor farmers of Beat Four. But it is also the case that Faulkner focuses on "an alternative community consisting of blacks, women and children; it is a community of minorities, marginalized on the threshold of the dominant community of adult, white men" (Morris and Morris 224). This group alone is willing to act on Lucas's behalf. The white men, or those with more social power than most, are notably lax and complacent when the crisis arises. And those upper class whites who later help Lucas, such as Chick's mother, do so only after the life-threatening risks have been taken. While the "alternative community" places emphasis on the positive liberty to take principled action in society, the prominent town lawyer speaks of the need for engagement only after his young nephew argues that injustice cannot be excused, and that "'somebody with a strong enough stomach'" has got to take the necessary action. "'Yes,'" Stevens says. "'Some things you must always be unable to bear. Some things you must never stop refusing to bear. Injustice and outrage and dishonour and shame. No matter how young you are nor how old you have got. Not for kudos and not for cash: your picture in the paper nor money in the bank either. Just refuse to bear them. That it?'" (ID 199, 201). It can be said that in "The Bear," Faulkner pointed to Ben, Lion, and Sam Fathers as comprising the "good community." (2) Like Miss Habersham, Chick, and Alec, they possess an inordinate amount of courage and an acute sense of honor, while standing as exemplars of a nobility of living. One of the differences, however--one that points to the shift in Faulkner's career--is that the earlier group inhabited a realm of near fantasy, a threatened and fast-fading idyll where the values of a traditional manhood were of primary concern, while the later group makes the pursuit of social justice its primary concern and activity in a crisis-ridden Southern society. The mature Faulkner's emphasis on principled action, and on social and moral development, stands in contrast to the earlier motifs of retreat and ineffectuality. In Go Down, Moses, Ike takes the step to support Fonsiba with the 1,000 dollar legacy-apparently seeking here the freedom to act according to what he has learned, particularly of his past. But this attempt more or less reeks of failure and fruitlessness, and it is not a line of thought and action that he replicates; it is rather a one-time effort. Seeking freedom from the world's corruption, Ike repudiates his heritage and conclusively withdraws into a closed inner sphere, thereby breaking his bonds with the human community and crippling his ability to act on behalf of the common good. The younger Faulkner not only refuses to examine the possibilities of positive liberty, he also suggests with a profound grimness that negative liberty itself is an unattainable ideal. Ike's quest for freedom from all that is unethical collapses into absolute failure as ghosts return in the form of Roth's betrayed lover, confronting and defeating him before his death. Similarly, Fonsiba's independence is seen as pure illusion as she and her husband are saved from starvation not by their own hands, but by the McCaslin inheritance money. While the mature author stresses the possibilities of social action, in the early novel his characters are disengaged, helpless before "evil," and hopelessly unfree. It is of course necessary to point out Faulkner's limitations, failures, and underlying prejudices with regard to race relations, and in so doing, to uncover the racism hidden deep in the institutions and in the mind of the society that he represents. But it must be taken into account that Faulkner was writing from within "a society in which acceptance of the inferior social position of the Negro" was everywhere present, a society which considered "segregation and the categorical inferiority of Negroes as values" (Killian and Grigg 103). Like Chick, Faulkner is ultimately bound by the influence of his time and place. And although the effort is there, it is evident that he is not able to transcend, in a manner acceptable to the reader of today, his personal and environmental limitations. But again, similar to his boy hero, Faulkner questions his own assumptions and struggles against them. He creates for himself a new understanding of, and a new approach to, the social world and his art. (1) Throughout the 1950s Faulkner publicly contemplated and debated civil rights issues. Although he attempted to maintain a "moderate" stance intended to accommodate both sides and to promote peaceful and gradual change, he himself came under fire as this stance proved to aggravate rather than accommodate the opposing parties. In 1956, he made statements which seemed not only to discredit his appeal for peaceful change, but also his credibility as a thinker and speaker. Moved by the threat of military intervention in Southern affairs, he is quoted as saying: I don't like enforced integration any more than I like enforced segregation. If I have to choose between the United States government and Mississippi, then I'll choose Mississippi. What I'm trying to do now is not to have to make that decision. As long as there's a middle road, all right, I'll be on it. But if it came to fighting I'd fight for Mississippi against the United States even if it meant going out into the street and shooting Negroes.... I will go on saying that the Southerners are wrong and that their position is untenable, but if I have to make the same choice Robert E. Lee made then I'll make it. (LG 260-62) Responding to the controversy surrounding this interview, Faulkner wrote a public letter explaining that "If I had seen it before it went to print, these statements, which are not correct, could never have been imputed to me. They are statements which no sober man would make, nor, it seems to me, any sane man believe" (LG 265). So was this then an inaccurately recorded statement, the regrettable outburst of a drunken man, or both? It does seem that during this period, Faulkner had in fact been drinking heavily. Worried that Autherine Lucy would be murdered upon entering the University of Alabama, he had tried to calm his anxiety with alcohol (Polk 136). But such explanations succeeded neither in exonerating Faulkner, nor in reducing the damage done to his credibility as a spokesman for Southern affairs. Instead, the interview served to corroborate the view that for all the rhetoric Faulkner was just another reactionary Southerner standing in the way of genuine social and moral progress. Faulkner's paternalism further complicates his position on civil rights. In "A Letter to the Leaders of the Negro Race," he advises black readers to ensure that they are "worthy" of equality: they must meet "the responsibilities of physical cleanliness and of moral rectitude, of a conscience capable of choosing between right and wrong and a will capable of obeying it, of reliability toward other men, the pride of independence of charity or relief " (ESPL 112). Accompanying such "recommendations" is the advice to "go slow," to be flexible, not to demand "immediate and unconditional integration," but to graduate slowly to this condition (ESPL 87). Yet, Faulkner did recognize that such a policy frustrated black people who were, after all, struggling for basic rights and liberties. But he also apparently believed that his was an objective and positive perspective which should be considered: "'Perhaps it is too much to ask of them,'" he said, "'but it is for their own sake'" (LG 258). He held to his view on the grounds that it would prevent bloodshed; that equality could be gained more successfully through peaceful and gradual change: "This was Gandhi's way" (ESPL 109). At the same time, however, the amount of time required for this progress to take place was never specified in this essay--and he had once suggested three hundred years. Faulkner's fear was that race riots and an armed conflict between federal troops and Southern whites would break out if changes were brought about abruptly or forcefully. From his standpoint, "'the Southern whites are back in the spirit of 1860,'" and the attempt of the Supreme Court to enforce school integration with a "legal edict" in 1954 only increased the risk of violence (LG 258). Noting that Northerners misunderstand Southerners as an inbred, illiterate, and inherently violent people whose social crises can be remedied only by federal intervention, he argued that the North failed to see that the problem was complex, and that society could not be purged of its racial hatred by police force or by the institution of laws (ESPL 88). For Faulkner, the North failed to realize the extent to which white Southerners would go to preserve their power: "What that [Civil] war should have done, but failed to do, was to prove to the North that the South will go to any length, even that fatal and already doomed one, before it will accept alteration of its racial condition by mere force of law or economic threat" (ESPL 89). Given this threat of violence, Faulkner called for the adoption of a cautious, pragmatic approach. In the midst of crisis, he suggests, the development of a practical strategy must take priority over issues of morality: "'We know that racial discrimination is morally bad, that it stinks, that it shouldn't exist, but it does. Should we obliterate the persecutor by acting in a way that we know will send him to his guns, or should we compromise and let it work out in time and save whatever good remains in those white people?'" (LG 261). In order to achieve progress by non-violent means, Faulkner advised that the Southerners should be made to feel that they are in control, that they themselves have initiated the integration process. Whites must be given the time to become conscious of their crimes so that they themselves, provoked by guilt and shame, would work for justice and equality. Such a strategy was devised in order to defend the rights of blacks and whites alike: the rights of the "white state" needed to be defended from external intervention, just as those of the black community needed to be recognized by white Southerners. It is easy to see that the non-fiction functions as a battleground for conflicting values; that Faulkner himself was divided by a more progressive sensibility and a kind of paternalism that characterized earlier members of the Faulkner clan; that he was divided by his loyalties to the cause of black equality and to the concerns of the larger white community in which he was an insider. To put it simply, Faulkner's stance on civil rights was highly confused and contradictory, and although he endeavored to expose the faults in the ideology of the established order, he was always under its influence, and identified with it to a large extent. (2) This point was suggested to me by Susan V. Donaldson. WORKS CITED Backman, Melvin. Faulkner: The Major Years: A Critical Study. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1966. Berlin, Isaiah. Four Essays on Liberty. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1969. Blotner, Joseph. Faulkner: A Biography. Vol. 2. New York: Random, 1974. Brinkmeyer, Robert H. Jr. "Faulkner and the Democratic Crisis." Faulkner and Ideology: Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha, 1995. Ed. Donald Kartiganer and Ann J. Abadie. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1997. Brodsky, Louis Daniel. William Faulkner: Life Glimpses. Austin: U of Texas P, 1990. Davis, Thadious M. Faulkner's "Negro": Art and the Southern Context. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1983. Faulkner, William. Essays Speeches and Public Letters by William Faulkner. Ed. James B. Meriwether. New York: Random, 1966. --. Go Down, Moses. 1942. New York: Vintage International, 1990. --. Intruder in the Dust. 1948. New York: Vintage International, 1991. --. Lion in the Garden: Interviews with William Faulkner 1926-1962. Ed. James B. Meriwether and Michael Millgate. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1980. --. Selected Letters of William Faulkner. Ed. Joseph Blotner. New York: Random, 1977. --. "Shall Not Perish." Collected Stories of William Faulkner. New York: Vintage, 1977. Gold, Joseph. William Faulkner, A Study in Humanism: From Metaphor to Discourse. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 1966. Hoffman, Daniel. Faulkner's Country Matters: Folklore and Fable in Yoknapatawpha. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1989. Honnighausen, Lothar. William Faulkner: The Art of Stylization in his Early Graphic and Literary Work. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1987. Jameson, Fredric. "Reflections in Conclusion." Aesthetics and Politics. London: Verso, 1994. Jehlen, Myra. Class and Character in Faulkner's South. New York: Columbia UP, 1976. Killian, Lewis, and Charles Grigg. Racial Crisis in America: Leadership in Conflict. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1964. Marcuse, Herbert. One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. London: Ark, 1986. Millgate, Michael. William Faulkner. London: Oliver and Boyd, 1963. Morris, Wesley, and Barbara Alverson Morris. Reading Faulkner. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1989. Nicholls, Peter. Modernisms: A Literary Guide. Berkeley: U of California P, 1995. Polk, Noel. "Man in the Middle: Faulkner and the Southern White Moderate." Faulkner and Race: Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha, 1986. Ed. Doreen Fowler and Ann J. Abadie. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1987. Singal, Daniel J. William Faulkner: The Making of a Modernist. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1997. Vickery, Olga. The Novels of William Faulkner: A Critical Interpretation. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1964. Wittenberg, Judith Bryant. Faulkner: The Transfiguration of Biography. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1979. Dimitri, Carl J. Source Citation Dimitri, Carl J. "Go Down, Moses and Intruder in the Dust: from negative to positive liberty." The Faulkner Journal 19.1 (2003): 11+. Literature Resource Center. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. Document URL http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.denverlibrary.org:2048/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA171020 103&v=2.1&u=denver&it=r&p=LitRC&sw=w