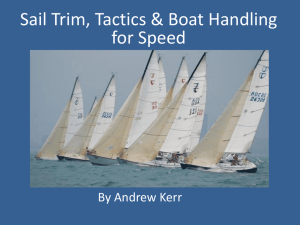

Sailing Instructions, main, genoa, spinnaker

advertisement

Some details about knots http://www.teachmetosail.com/Knots-signup.html Introduction The mainsail is the most durable and flexible sail on the boat. It has to cover a varied wind range. While the mainsail provides a large portion of power, it also affects the boat's directional control. The main sail helps to steer the boat by functioning like a trim tab on the keel. The leech, has an important influence on the directional tendency of the boat. A closed leech directs the airflow to windward, creating a large side force to leeward at the stern of your boat. This creates weather helm and tends to push the bow of the boat to windward. Similarly, an open leech allows the air to flow easily off the mainsail without developing as much sideways force This will result in less windward helm. Mainsail Trim Procedure The five basic steps of main sail trim are as follows: 1.Set twist with mainsheet tension. On a mainsail, twist is controlled by the amount of mainsheet tension, as well as the amount of tension on the vang. The mainsail leech is the best indicator of how much the sail is twisted. To set the proper sail twist, trim the mainsheet until the top batten is parallel to the boom. When the sheet is eased, the main has a very twisted shape, with the top batten falling off to leeward . As you trim the sheet, the top batten angle narrows until it is parallel with the boom. Trimming harder will take away all the twist and close the upper leech. The best average setting for the top batten is parallel to the boom. With the top batten in this position, the top batten telltale should stream aft between 50 and 90% of the time. This tell tale, attached to the aft end of the top batten and extending 8 to10 inches beyond the leech, indicates whether the upper leech is stalling. When the leech is stalled, the telltale curls around to leeward of the main. Twisting the main sail more will open up the leech and reestablish the airflow. In choppy conditions, after tacks and in light airs, ease the sheet to open up the leech slightly and prevent stall. The primary means for adjusting depth in the upper two-thirds of the main is mast bend. Bending the mast moves the luff away from the leech, which does several things simultaneously – it flattens the sail, opens the leech and moves the draft aft. If you see overbend wrinkles, ease the backstay tension or tighten the checkstays/runners to straighten the mast. 2.Outhaul The best way to control depth in the lower third of the main is with the outhaul. The tighter the outhaul, the flatter the bottom of the sail. If the waves are big for the wind, ease the outhaul slightly to give more power. If the waves are small for the wind, as in an offshore breeze, pull on the outhaul to flatten the sail and reduce drag. Besides depth, the outhaul also changes the tightness of the lower leech. Easing the outhaul adds depth to the foot of the main. Conversely, tightening the outhaul opens the lower leech. The tighter the lower leech, the more windward helm you have. That's why it makes sense to tension the outhaul in heavy air to open the leech and reduce the helm forces. 3.Set draft position with luff tension Once you've set the overall depth of the sail, the next step is to position the area of maximum draft. This is usually done with the cunningham tension. The cunningham applies tension to the luff of the main, and this controls draft position. Tighten the cunningham to move the draft forward; ease it to let the draft move aft (see below). In general, the more you bend the mast, the tighter you need to pull the cunningham to get the draft in the right place. You'll also have to pull the cunningham harder on an older main, because a sail's draft moves aft with age. In light airs, keep the cunningham quite loose. In light airs, lower the main halyard (especially downwind) to get the proper luff tension. 4.Set helm balance with traveller position The main sheet traveller controls the angle of the mainsail to the boat's centreline and to the wind This has a large effect on helm. 3 to 5 degrees of windward helm is the ideal setting. 5.Fine-tune the total power of the main with the above controls The final step in mainsail trim is continual evaluation of the sail's power. The main trimmer must keep track of the boat's heel angle, speed and pointing ability. The most obvious indication of over-powering is the angle of boat heel. Boatspeed and the amount of windward helm are actually more sensitive and accurate indicators of over powering. Measure the rudder angle required to sail in a straight line. The ideal angle is about 3 to 5 degrees of windward helm. If you have more than this, you are overpowered. Depower the mainsail by bending the mast, opening the leech, easing the sheet, dumping the traveller, and reefing if necessary. These adjustments are simply changing the total power being exerted by the mainsail. Since most of the main's power is side force, adjusting the amount of this power affects windward helm. Ideally you should get windward helm down into the acceptable range. Introduction The genoa is an important sail because it provides a large portion of the driving force of a yacht. There are two reasons for this: The genoa has no mast in front of it to create turbulence and spoil clean flow. It sails in the continual lift that is caused by the mainsail's continuous airflow. In general you should trim your genoa for drive and your main primarily for helm balance. In strong winds the maximum sail area simply over heels the boat, and it's better to reduce water drag by changing down to a smaller jib. This will maintain lift at a maximum while lowering water drag. The crew who tends the genoa need a methodical approach to cover all variables and maintain the best trim. The six basic steps of genoa trimming as as follows: 1. Select the correct genoa for the relevant wind conditions The best way to make good sail selection choices is to keep a record of the headsails you use with wind velocities and boat performance. After a while you'll have an extensive chart as a guide or experience will guide you. Genoa Wind Ranges Your genoa determines your ultimate sail power and the total heeling force. As a general rule, if your heel exceeds about 25 degrees, change down to a smaller genoa. Helm balance is another consideration. If you have too much helm, changing to a smaller genoa may be the way to solve the problem. Headsails are generally designed for a maximum wind velocity. It is therefore a good idea to tag your sails with their relevant wind velocities, so you will know when to change the sail. Advise on the headsail wind velocities can normally be obtained from your sail maker. 2. Determine the efficiency of the genoa with the lead angle. Many new yachts today are able to move their jib leads sideways as well as fore and aft. This allows much better control over the lead angle. Sheet inboard when you have some or all of the following conditions: Medium air Flat water Experienced helmsman You want to point higher. No backwind in the main Use a wider sheeting angle when conditions demand that you sacrifice some efficiency for more reliable power: Very strong or very light wind Genoa at the top of its range Excessive backwind in the main Heavy chop or sea Inexperienced helmsman In general, pull the genoa sheet inboard in ideal conditions and outboard to play it safe at other times. If your boat isn't rigged with a side track, use a barber hauler, that pulls the genoa clew outboard or inboard. 3. Set sail depth and twist with the sheet. The genoa trimmer's primary responsibility is to maintain optimal sail shape as wind velocity and other conditions change. Genoa sheet tension must be adjusted to preserve the same basic trim. The trimmer's secondary responsibility is to help the helmsman steer the boat. For example, the sheet should be let out for big waves or sudden lifts, and pulled in for flat spots. When the helmsman brings the boat back up to speed on the wind, the trimmer should slowly re-trim the sheet. All this requires constant communication, observation and concentration. Pulling in the sheet generally allows you point higher. Easing the sheet has the opposite effect, more speed and less pointing ability. Sheet tension should be changed with every change in wind velocity and direction. When a puff hits, the genoa sail stretches and gets fuller. To compensate for this change, trim in the sheet. If the wind velocity decreases, the genoa becomes less pressurised and flatter. Ease out the sheet to make the sail fuller and maintain speed through the water. Sailing through oncoming waves requires the same kind of sheet tensioning adjustments in order to maintain boat speed. The helmsman should steer up the front of a wave and down the back. The trimmer has to adjust the sails constantly to meet these changing apparent wind angles. Good genoa sheet trimming is a full time job. The genoa trimmer must continually change the setting and the trim for every change in wind, wave, and steering conditions in order to keep boat speed at the maximum. 4. Set depth and twist with the fore-and-aft runner car. The fore-and-aft position of the genoa has a significant effect on twist and depth in the foot of the genoa. When sail twist matches wind twist, the genoa will be perfectly trimmed from top to bottom. Now the sail should luff simultaneously up and down the luff when you head up slowly past closehauled. The lead position is set by luffing up slowly and watching the telltales which should "break" evenly from top to bottom at the same time. If the top telltales flutter before the bottom, the sail is twisted too much. This is corrected by move the lead forward. If the bottom telltales luff first (or the top ones stall), The move the lead aft. 5. Set depth and twist with backstay tensioners. The backstay or running backstay affect depth in the middle and upper genoa sections by controlling sag. To a lesser extent, they affect twist. When you have sailing conditions that require power in the sail ie; light airs, choppy water – you will need a deep sail. This is achieved by by easing off the backstay tension. In light airs backstay tension should be about 25% of maximum. It will be too loose if the luff curls like a spinnaker. Backstay tensioners should be adjusted continuously, in conjunction with the genoa trimmer and helmsman, to keep the boat sailing fast. 6. Set draft position with halyard tension. You should tension the halyard just enough to remove most of the horizontal wrinkles. Use the telltales The leeward telltales should always flow aft. If they hang limp, the sail is stalled, and the genoa trimmer should ease the sheet immediately to re-attach flow. Steering the boat in light airs It's important for the genoa trimmer to help the helmsman respond to changes in the wind. The genoa trimmer can always react faster than the helmsman. If the helmsman tries to speed up a tack or gybe by jamming the tiller hard over, the rudder will effectively brake the boat. The genoa trimmer should let the sails turn the boat by easing the sheets. This will help the helmsman head up slowly, and the jib can be re-trimmed. This will maintain the best boat speed. When your genoa gets old, tired and out of shape. Sooner or later, all genoa sails get old and their shape starts to change from the optimum. Ageing is inevitable and a fact of life. There are a few steps you can take however to counteract the effects of ageing on a sail as follows: Trim the foot harder (closer to the chain plates) to bring the upper part of the sail closer to the spreader. Use more halyard tension to pull the draft forward. This will give you a rounder entry and more power. Increase the lead angle slightly to reduce the main sail backing caused by roundness near the leech. Move the lead back slightly to twist the leech more. Genoa Terms Genoa Sheet: Affects twist, depth and angle of attack. Adjust to shift gears and help steer the boat. Genoa Halyard: Controls draft position. Begin with halyard just tight enough to eliminate horizontal wrinkles. Has more of an effect on sail made with elastic materials. Backstay Or Runner: Limits head stay sag. Controls overall depth of genoa, and effects draft position. More sag gives more power and makes steering easier. Genoa Lead: Fore-and-aft position alters twist. Athwartship position affects twist and sail efficiency. Telltales: Should break evenly from top to bottom. Leeward telltales should (almost) never stall. Crew Positioning BEFORE HELM "Prepare to tack" Prep old sheet. Take winch handle out. Load new sheet WINCH 2 on drum. MASTMAN Clear jib sheet. WINCH 1 BOWMAN Clear jib sheet. DURING "Tacking" Release traveller. AFTER Verbalise acceleration. Watch boat speed. Release jib sheet. Wind in Jib Trim mainsheet and adjust traveller. Tail new sheet. Trim jib sheet. Move weight. Make sure jib clew goes freely around mast. Skirt jib foot. Move weight. Introduction One method to hoist the spinnaker is described below. Each crew position is broken down into tasks that need to be simultaneously performed by each crew member to make the various manoeuvres successful. Hoisting the spinnaker Helmsman Decides when to set the spinnaker. Orders the pole to be set. When the pole is set and the boat is at the mark, bear away and ease the mainsail while calling "Hoist". Steer toward the next mark while making finer adjustments to mainsail trim by using the sheet, easing the backstay and checking if other sail controls .are eased Bring any spinnaker mistakes to the crew's attention. Trimmers Once the pole is set and ss the skipper bears away, ease the jib out 1-2 feet. While the spinnaker is being hoisted, continue to pull the guy until it meets the pole, then pull the pole 90 degrees to the wind. Grab the spinnaker sheet and fly the spinnaker by continuously easing and trimming. Mast Man While keeping weight outboard, assist the bowman by raising the uphaul. Secure the downhaul. When the guy is being pre-fed, hoist the spinnaker halyard. When the spinnaker is up and drawing, release the jib halyard. Adjust twing lines Help the trimmer with the guy if it is windy Bowman Set the pole and set the guy through the outboard end. Make sure it is not twisted. Once the chute is up, go forward to take down the jib. Once the spinnaker is up and flying, each crewmember must pay attention to their job. The helmsman should always know where the mark is in relationship to his course. The trimmers must constantly trim the spinnaker as failure to do so will cause the spinnaker to collapse. The mast man should tell the helmsman where the boats behind your boat are steering. The bowman should always be ready to gybe the pole. The trimmers should always be in a position to release the sheets if a broach occurs. For this reason spinnaker sheets should not be tied off. Introduction One method to hoist the spinnaker is described below. Each crew position is broken down into tasks that need to be simultaneously performed by each crew member to make the various manoeuvres successful. Hoisting the spinnaker Helmsman Decides when to set the spinnaker. Orders the pole to be set. When the pole is set and the boat is at the mark, bear away and ease the mainsail while calling "Hoist". Steer toward the next mark while making finer adjustments to mainsail trim by using the sheet, easing the backstay and checking if other sail controls .are eased Bring any spinnaker mistakes to the crew's attention. Trimmers Once the pole is set and ss the skipper bears away, ease the jib out 1-2 feet. While the spinnaker is being hoisted, continue to pull the guy until it meets the pole, then pull the pole 90 degrees to the wind. Grab the spinnaker sheet and fly the spinnaker by continuously easing and trimming. Mast Man While keeping weight outboard, assist the bowman by raising the uphaul. Secure the downhaul. When the guy is being pre-fed, hoist the spinnaker halyard. When the spinnaker is up and drawing, release the jib halyard. Adjust twing lines Help the trimmer with the guy if it is windy Bowman Set the pole and set the guy through the outboard end. Make sure it is not twisted. Once the chute is up, go forward to take down the jib. Once the spinnaker is up and flying, each crewmember must pay attention to their job. The helmsman should always know where the mark is in relationship to his course. The trimmers must constantly trim the spinnaker as failure to do so will cause the spinnaker to collapse. The mast man should tell the helmsman where the boats behind your boat are steering. The bowman should always be ready to gybe the pole. The trimmers should always be in a position to release the sheets if a broach occurs. For this reason spinnaker sheets should not be tied off. Introduction The methods available for maintaining the proper trim of a spinnaker are limited. The primary tools consist of setting the spinnaker pole position and fine tuning the sheet position. The spinnaker pole position can be set fore and aft and up and down. Sheet position is varied primarily by pulling it in or letting it out. With these two controls, the spinnaker can be set to its optimum position. The spinnaker is a versatile sail which can be used when the wind is blowing anywhere from 60 to 180 degrees off the bow. The optimal sailing angle is determined by the wind strength. In strong winds, flying the spinnaker as close to the wind will be difficult as the boat will be tend to be overpowered by the spinnaker at the closer angles. If the wind is too light, sailing at the broader angles will be too slow. At the forward end of this range, from 60 to 130 degrees, the wind will be flowing across the spinnaker from the luff to leech. At some point behind 130 degrees, or thereabouts, the wind will blow directly into the spinnaker. Trimming for a Reach When the wind is flowing across the spinnaker from luff to leech, then the spinnaker is on a reach. If the wind is forward of abeam, the pole should be as close as possible to the forestay. If the pole rubs against the stay, there is potential risk of damage to the spinnaker pole, the rig, or both. Fore and aft position is controlled by the guy. The sheet should be trimmed just enough to prevent the sail from collapsing. The trim should be constantly trimmed by easing the sheet slightly until the luff commences to curl, then trimming again when the curl becomes excessive. Telltales on the leeches of the spinnaker midway between the head and clews will help in astertaining trim. When reaching, read the telltales as you would on a jib. Keep both the windward and the leeward telltales streaming straight back. When both are flying aft, the leading edge of the chute will curl slightly. This is the optimum trim. The spinnaker pole height is adjusted by means of the uphaul and the downhaul. In any given wind condition, the clew will find its own height. The pole height should be adjusted to match that found by the clew. If the pole is slightly lower than the clew, the sail will become asymmetrical. Asymmetrical trim will be faster on close reaches. Putting the pole higher than the clew moves the draft behind the middle. This always produces slower going. You should never carry the spinnaker pole higher than the level the clew is flying at. At all times, sufficient tension should be maintained on the uphaul, the downhaul and the guy to keep the outboard end of the pole firmly in position. The mast end of the pole should be moved up or down on its track or fixing to keep the pole perpendicular to the mast. Generally adjustments to the inboard end are a low priority item. Unless it’s grossly out of position, you should not waste time on it until everything else is set correctly. The spinnaker pole position should always be perpendicular to the wind. The pole position needs to be continuously trimmed by moving the pole fore and aft to maintain the 90 degree angle to the wind. The spinnaker sheet will need to be adjusted accordingly to keep the sail in trim. Trimming for Run On a run, with the wind blowing directly into the sail, it is desirable to present as much area as possible to the wind. The pole should be kept as far aft as possible without making the foot of the spinnaker too flat. In a good breeze (when the wind is blowing over 14 knots), the clew may seek to rise higher than is desirable. If the foot gets too high, you lose sail area. Moving the spinnaker sheet forward will keep the clew down. Proper downwind trim involves balancing the extra thrust resulting from the aerodynamic forces acting around the edges of a deeper setting against the greater projected area obtained with a flatter setting. Normally, best results are obtained at the flatter end of the range, but remember that it is quite possible to trim the sail too flat or have the foot too low. The way to find the best spinnaker sail shape is to experiment while watching the speedometer. Spinnaker Takedowns Releasing the Snap Shackle Method The guy sheet is let out until the pole reaches the forestay. The guy sheet must be controlled in order to avoid damage to the forestay, or damage to the spinnaker pole. The spinnaker pole is lowered until it can be reached easily by the bowman who opens the snap-shackle that connects the guy to the spinnaker. As the spinnaker is released from the guy, the bowman gathers in the foot of the spinnaker. The mast man eases the spinnaker halyard for the first third of the distance, which collapses the sail. Once the chute starts coming aboard, the rest of the halyard is eased as fast as the crew can gather without the sail falling in the water. The spinnaker sheet can then be stuffed into the spinnaker bag attached to the bow. Unclip the spinnaker halyard and store it on the mast. The spinnaker sheets can be left attached if an other spinnaker run is envisaged with the same spinnaker. How to Set a Spinnaker Quickly in Sailboat Racing A clean spinnaker set is one that goes up, fills and is trimmed quickly. At the weather mark, a good set can mean several boat lengths - a poor set can take you out of the race. Steps: 1. Run the tapes on the spinnaker to make sure it was packed well and will come out with no wraps. 2. Check to see that your halyards are not wrapped around the headstay or one another. 3. Alert your crew to ready for a spinnaker set. 4. Set the pole on the mast in the right position, and top the outboard end with the guy in the jaws before you hoist. 5. Prefeed the clew hooked to the guy to the end of the pole. 6. Snug the foreguy. 7. Hold the body of the spinnaker clear of the hatch or out of the bag so that it doesn't get hung up anywhere. 8. Feed the head of the spinnaker underneath the jib and over the lifeline. 9. Take the slack out of the spinnaker sheet and halyard. 10. Jump the halyard with quick, body-length arm pulls until it is topped. Tips: Practice spinnaker sets with your predetermined roles without any time pressure. Once everyone is comfortable with his or her roles, turn up the urgency level. Instruct crewmembers on where to look for snags and how to get the spinnaker unwrapped if there is a problem. Warnings: Beware of excessively large loads on big boats while flying a spinnaker. Use several wraps around a winch and wear sailing gloves to lessen the risk of rope burns on your hands. How to Take Down a Spinnaker Quickly in Sailboat Racing Ever tried to sail upwind with a spinnaker? A quick, properly executed takedown will help you round the leeward mark at full speed. Steps: 1. Run your halyards, sheets and guys through your hands and flake them out so they run clean. 2. Hoist your jib to take wind out of your spinnaker. 3. Head down and ease the main to blanket the spinnaker to reduce additional load. 4. Drop the pole to the deck. 5. Have your bowman grab the lazy sheet (or lazy guy as the case may be) and pull in the foot as you blow the sheet. 6. Ease the halyard quickly, but do not get ahead of the foredeck crew. 7. Have the foredeck crew swim the spinnaker in with large hand-over-hand pulls. 8. Blow the guy last and collect the remainder of the spinnaker until it is stowed down below. Tips: Practice takedowns when you are under no time constraints and talk about everyone's roles until the entire crew is comfortable. Slowly increase the speed and intensity in practice, then implement what you've learned on the racecourse. Instruct your crew on where to look first if something is hung up and not coming down cleanly. How to Round a Windward Mark in Sailboat Racing If you're on your first upwind leg, you'd better prepare for an exciting, trafficked windward mark. A solid rounding can mean several boat lengths or can launch you into a controlling position. Steps: 1. Read the race instructions to see whether there are any special mark-rounding procedures. 2. Look at the course chart to be sure you are rounding the correct mark. 3. Tack onto your final lay line to the mark. 4. Hook up the spinnaker, set the spinnaker pole, prefeed the guy and load the spinnaker sheet on a winch in a good trimming location. 5. Keep your weight on the high side until the driver begins the turn. 6. Stay high of the mark to allow for waves and current that could push you into it. 7. Begin the turn and ease the main and jib, jump the spinnaker halyard until it is topped, bring the pole back and trim the spinnaker. 8. Blow the jib halyard and drop the jib on the deck. 9. Steer the boat on a broad reach to maximize boat speed and then begin heading down towards the mark. 10. Settle into your downwind tuning roles. Tips: Overstand the mark and put some distance in the bank if you are unsure about your lay line. It's often better to reach for the mark fast than to throw in two more tacks. Keep calm when you're in the middle of traffic and maintain your rights on starboard tack until you are clear to jibe. How to Keep Your Lines Clean and Running Free When Sailing Lines control just about everything on a boat, whether it's a dinghy or big boat. Keep lines in good shape, and stay on top of them while under way and you will have smooth sailing and be able to perform quick maneuvers. Steps: 1. Run the full length of all lines through your hands checking for knots, twists and hockles. (Image 1) 2. Rig slowly, and make sure your lines are not run through the wrong block and/or under or inside of lines of which they should be on top or outside. (Image 2) 3. Walk the deck of your boat after rigging, and check for spots where lines are likely to hang up, such as hatches, cleats, stanchions, shrouds, windows and companionways. Tape over areas where it seems sensible to do so. (Image 3) 4. Instruct your crew on where to sit, stand and be on the lookout for line hang-ups. 5. Clean up the lines on deck and in the cockpit after every tack, jibe, sail change, and spinnaker sets and takedowns. This way, the next maneuver will go smoothly. 6. Rinse your lines with fresh water after use, coil them neatly and hang them in a dry place away from direct sunlight. (Image 4) click photos to enlarge 2. 1. 3. 4. Tips: Appoint one crew member to be in charge of cleaning up the lines while sailing, but make sure everyone knows what to look for and where to look if you have a hang-up. Teach your entire crew how to rig each line so that they understand its function and can fix it while under way should something go wrong. Soak salty lines in a bucket of fresh water with a small amount of mild soap to prevent them from getting stiff and rough on your hands. Warnings: Lines that are not rigged properly, get hung up or are in bad condition can cause hardware to break and, in turn, can cause injury or death - especially on larger boats with heavy loads. How to Wrap a Winch When Sailing There's more to wrapping or "loading up" a winch than meets the eye. Plenty can go wrong to slow your tack, foul your trimming or pinch your fingers. Steps: 1. Rig your sheets correctly, taking care to see that they run straight from the block to the winch without rubbing against anything that will inhibit trimming and cause damage to the line or hardware. 2. Run the length of the sheet through your hands to get out any twists and hockles. 3. Lay the sheet in the open palm of your hand, then begin wrapping it in a clockwise motion around the spool of the winch until you have three wraps. (Image 1) 4. Keep your hand above the winch as you wrap, taking care not to wrap the line around your hand or fingers. (Image 2) 5. Hold the line taut and free of slack so that it lies on top of itself, snug to the winch. There should be no overlaps or knots in the sheet. (Image 3) click photos to enlarge 1. 2. 3. Tips: Perform your wrapping motion as if you were stirring a large pot of stew. Pull the sheet after you've wrapped it to make sure it is grabbing the winch. With enough tension the winch should rotate and you will hear it clicking. Wrap your winch before you need it - while there is no load on your sheet. Warnings: Keep your fingers and hands ' if you're fond of them ' outside any wraps that might unexpectedly come under load. How to Read Your Telltales When Sailing Reading telltales is a challenge even for the most experienced sailors. Keeping them streaming aft is even more difficult, but with practice and constant attention, a good trimmer will stay on top of his or her telltales. Steps: 1. Sit in a place where you have an unobstructed view of your telltales, so long as it does not pose a ballast problem. 2. Work in tandem with your trimming and driving so that they are "in tune" with each other. 3. Ease the sail or head up if the leeward telltale is fluttering and lifting. 4. Sheet in or head down if the windward telltale is fluttering and lifting. 5. Make one adjustment at a time, taking a moment to notice its effects. 6. Keep your trimming and driving "as is" when both telltales are streaming aft. This indicates an even - and therefore efficient - airflow over both sides of the sail. Tips: Write down what works well and what feels slow. Make notes on the positions of your jib leads, the appearance of the foot and leech of the sail, the wind velocity and the waves. Keep the notes handy for quick reference prior to your races. Warnings: Staring at telltales all weekend long can drive a skipper crazy. Give your eyes a break every now and then, and relax between races. How to Keep Your Telltales From Sticking When Sailing Telltales are the lifeblood of a trimmer. When they stick, a trimmer loses his or her ability to read the wind accurately. Steps: 1. Clean your sail prior to hoisting. Wipe the telltale area with a moist rag, and then dry it completely, taking care to remove any salt or dirt. 2. Spray the telltale area with a dry marine lubricant to provide a slick surface. 3. Check to see that your telltales are both fastened to the sail securely and are long enough to flap freely, which will give you a better read. 4. Slap your sail firmly with an open hand if the telltales are sticking. When the sail is up and trimmed, the vibration from your slapping will knock the telltale loose. 5. Send your bowperson forward quickly to slap the luff of the sail or to free the telltale by hand only if you are not able to do it from the cockpit or the leeward rail. 6. Wash - or wipe - your sails with freshwater after use, and dry them thoroughly. 7. Store your sails either rolled or flaked carefully in their bags and in a dry place. Tips: Keep unnecessary weight off the bow whenever possible. If someone has to go forward to clear the telltales, pick the lightest person on board and have them move quickly. Place telltales away from stitching in the sail, where they are likely to get caught up. How to Perform a Safe Ducking Maneuver in Sailing If you're in doubt of crossing and don't have rights, you'd better duck and be decisive about it. Safe ducking will keep the insurance companies off your back and will keep you out of the protest room, the shipyard and the hospital. Steps: 1. Know your rights. If you don't have rights, be prepared to maneuver around your competitor. 2. Communicate with your crew members, and tell them to assume their ducking roles. 3. Wave the converging boat ahead. 4. Appoint a crew member to help with calling out distances. 5. Drive from the low side to give you a better view of the traffic to the leeward side. 6. Ease your traveler and main sheet, and crack off just a bit on the jib to give the helmsman greater control. 7. Fall off early enough to avoid any drastic maneuvers, and then head up as soon as it's safe. 8. Readjust for upwind sailing once clear. Tips: Put some speed in the bank. By falling off and easing your sails, you can maintain maximum boat speed, giving you the room to duck without losing ground. Understand that being greedy and chancing a cross can cause you to lose the entire regatta - not just a boat length. Be safe. You'll have more fun racing if everyone on the course comes home with limbs in tact. Warnings: No collision is worth the risk. Injury and even death can result from a sailboat collision. Taming the Spinnaker by Greg Fisher Flying the spinnaker often seems critical and in breezy conditions, downright scary. However there are a few guides and techniques that can help with the taming of this somewhat elusive sail. 1) Trim the sheet so that the luff has a slight curl… The spinnaker trimmer should constantly be trying to ease the sheet of the spinnaker so that the luff (leading edge) will constantly show a 6-10” curl. Without this guide it is tough to tell when the spinnaker is over trimmed. An over trimmed spinnaker will have a “hooked leech” just like a main or jib that is over trimmed and will close the important slot between the main and the leech of the spinnaker. Try to be smooth with the trimming of the sheet. Instead of the jerking the sheet in and out, try to gradually ease in and out with 1-2’ movements. 2) Keep the pole roughly perpendicular to the wind… Like the sheet, the pole position (the guy) can have a big effect on the trimming and performance of the sheet, and it too needs constant attention. Ideally the pole will be placed so that the pole is nearly perpendicular to the wind. Be conscious of pulling the pole too far aft and over squaring the spinnaker, making it too flat. Also, watch leaving the pole too far forward which will make the spinnaker too full, thereby losing valuable projected area. A great guide for determining pole position is to place a telltale on the topping lift a foot up from the pole. Don’t ignore the guy…it needs just as much attention as the sheet! 3) Set your pole height so that the two ends are even. Since most one-design spinnakers (like the Flying Scot) are symmetrical sail should be evenly set. The topping lift should be adjusted often (especially in puffy, shift conditions) so that the two clews (corners) are even. The pole will need to be lowered in lulls and quickly raised back up in puffs. Remember that pole height is based on the shape of the sail NOT on the angle of the pole to the mast or to the forestay. Often, it becomes difficult for the trimmer (or topping lift adjuster) to see the leeward clew as it is hidden behind the main. In that situation, a great guide (and the most accurate I might add), is to set pole height so that the center seam of the spinnaker (most spinnakers have a seam that runs from the head down to the middle of foot skirt) is parallel to the mast. Because the pole height needs attention (like the sheet and the guy and especially in light winds) it’s a great idea to have the cleat for the topping lift in a convenient spot for the crew to easily reach. 4) Set the spinnaker halyard set so the spinnaker is 6-8” off the mast. Keeping the slot between the main and spinnaker open Kelly Gough sailing with his two clew seven and the centerseam parallel to the mast. Notice how flat his boat is. and flowing up high is just as important as down low. Leaving the halyard eased so that head of the spinnaker will float away from the mast will help the spinnaker fly smoother. When sailing dead down wind and in breeze, the head of the spinnaker can rotate a bit to windward slightly and help the spinnaker out from behind the main. On our boat we actually tie a stopper knot in the halyard that stops the spinnaker at right spot for every hoist…and we don’t even have to remember! 5) When the skipper and the trimmer need to work together. Obviously whenever the skipper needs to alter course (for a mark, for a wave, for a puff or lull…) he should communicate that change before he actually begins. Allowing the trimmer to anticipate the change of course will make his job of keeping the spinnaker set properly much easier. In a puff, if the trimmer eases early (because he is aware of the puff and the ensuing change of course) the skipper can bear off and maintain control much more smoothly. In light winds, or in a lull, a subtle sheet trim as the skipper heads up (but not after!) will keep the boat at top speed. In addition, the crew needs to communicate their needs as well. In light winds the trimmer should constantly keep the skipper apprised of the pressure they feel in the sheet…If the tension they feel suddenly becomes much The halyard is off the mast 6” and the lighter in relation to what they had been sensing, they sheet is eased so the luff is curled 8”. should warn the skipper and the skipper may in turn want to slowly head up (called “heating up”) to build or maintain speed and pressure. Once the pressure on the sheet returns (assuming the wind hasn’t completely died!) the trimmer can encourage the skipper to slowly bear back off (“burning the pressure off”) to a lower, closer course to the mark. For sure, sailing downwind should not be a quiet time- constant chatter is imperative to top performance. 6) When in trouble, dump the spinnaker sheet last! Its best to do everything you can to keep the boat under control in a puff before easing the sheet way out. Collapsing the spinnaker will greatly slow the boat way down and when it does fill again it can fill with such great force (because the boat is so slow) that the load could easily throw the boat out of control a second, or a third, or a fourth…time. Instead, make sure every other option is exhausted. The main sheet of course should be eased way out and quickly as the skipper bears off to keep the boat under the spinnaker (never head up in a puff downwind!). Dump the boom vang to completely depower the main. Make sure the centerboard is at the right height…and the helm is neutral (the boat wants to steer a steady course even in a puff). Sometimes on a windy reach, the board may be hoisted as much as halfway or even ¾ of the way up to keep the helm balanced and allow the skipper to steer the boat instead of the boat taking control of the skipper. Finally make sure the boat is very flat as the puff approaches. As a very last resort and only when a capsize in imminent, let the sheet way out. But be sure to only trim it back when the boat is steered lower and balanced. 7) What is the best way to gybe? Try to decide what is the best method, for you, for gybing the spinnaker and use that method in all conditions. This little trick will eliminate a lot of variables in the “heat of the battle”. In some boats (and I found in the Flying Scot) gybing the spinnaker with the pole still attached (but the old guy is released from the guy hook or the old weather twing is released) works great. After the gybe (the boom has crossed and filled on the new gybe), the foredeck will reach up and remove the pole from the mast, the guy and then reattach to the new guy and then the mast. This way the crew is always to windward when the spinnaker is loaded up. Some have found that disconnecting the pole from both the mast and the old guy and allowing it to dangle through the gybe works well (our old way in the Flying Scot). This way the pole work is “halfway done” and the gybe is in some ways quicker. This method can work well as long as the pole doesn’t get fouled in the pole lift or the jib if it is still up. Some even jump right up on the deck in order to gybe the pole as the boat is gibing…for more experienced crews (but not suggested for the Flying Scot) this method can work fine…but make sure you’re wearing non-slip shoes!! 8) How to get it down!?! After some really great work flying the spinnaker the trickiest part may well be the “retrieval”. The drop can be pretty difficult as the boat slows down as the leeward mark gets closer and the crew prepares for dousing the spinnaker. As a result, in breeze, the boat becomes more loaded and sometimes more unstable. On most racecourses its best to drop the spinnaker to the windward side so the spinnaker will come back up on the leeward side the next hoist. Sometimes even if the ideal hoist the next time would signal a drop to leeward, it still may be best to drop the spinnaker to windward (and deal with the switch or windward hoist later), for safety’s sake. During a windward drop, the pole is best completely removed and placed back in the cockpit before the drop. Ideally if the boat is sailing dead downwind the spinnaker will remain flying and then the entire team can grab the spinnaker and pull it down together. Leaving the pole up and dangling (but obviously not attached to the guy or the mast) and pulling the spinnaker down around it can, and certainly has been done but it can also lead to a nice tangle and sometimes a ripped spinnaker. However, when approaching a leeward mark on a windy, tighter reach a leeward drop may be the only way to get the spinnaker down. If it’s lighter wind it’s not a big issue…the crew simply climbs to leeward while the guy and sheet are released (only when the foot is gathered together!) and pulls the spinnaker inside the boat while the halyard is uncleated. But if its windy, and the boat is overpowered sending a crew to leeward asking for a swim. Instead consider nucleating the halyard first. Huh? Yep, this system can work exceptionally well if 1) the halyard is completely free to run ( read previously checked and coiled!), 2) the sheet and the guy remained fully trimmed and its blowing over 10-12mph. The spinnaker will float gracefully out to leeward like a flag barely kissing the water. Since the boat is depowered the crew can now slide to leeward and grab the spinnaker in the middle of the foot skirt. The guy and sheet will be let go and the spinnaker can quickly be gathered into the boat. This is a good one to practice first but with just a little work it can be incredibly smooth. 9) Practice, practice, practice…. As with any technique, practice makes perfect. Give these suggestions a try. Put on an older spinnaker, get out on the water with your team and blast around a practice course until you’re confident! Sailing more controlled, and with more confidence will mean better results AND more fun. Good luck! Getting the most out of your spinnaker light vs. heavy air With Monday comes a little schoolin' for y'all. Our friends at Halsey Lidgard Sailmakers, in this case Toby Halsey, wrote an article for us covering spinnaker trim. Enjoy the piece, and hopefully there's a little something for everyone here. The Ed Lets face it, if you can sail your downwind legs with quick spinnaker hoists and drops and clean gybes without collapsing your kite, you're going to save a lot of time around the race course. There are however, different techniques used in light and heavy air to maximize your efficiency. Have you ever rounded the windward mark in light air, hoisted the spinnaker quickly, and then ran over it? The lighter the breeze, the more difficult it is and the longer it takes to get it flying again. There are two good ways to avoid this common problem: first, the helmsman needs to have a slow, smooth bear away, and second, the genoa needs to come down quickly. The bear away Proper Running needs to be smooth, slow, and gradual. Any jerky movements or a fast bear away will result in a velocity header. Because its light air, your going to be sailing hotter angles anyway, so keep the boat moving and the apparent wind on. The other thing helps is a very quick genoa drop. Whatever little air there is needs to get to the spinnaker immediatelydon't block it with the genoa. A good pitman can have the genoa falling as he or she is tailing the spinnaker halyard. The bottom line is boat speed, so be patient, keep the heat on until your settled, and then try to start sneaking it down. In heavy air, the hoisting techniques are almost the opposite as light air. Because your best vmg is going to be very deep, the helmsman needs to bear away quickly as the main trimmer smokes the sheet and perhaps eases the vang so the boom doesn't hit the water. Pre-feed your afterguy to a foot past the headstay and sneak as much as you dare with hoist. If you overdo either of these two moves, it may result in the spinnaker filling before you want it to. As the boat begins to come upright hoist the spinnaker as fast as possible. The mainsail (fully eased) will block the wind just long enough to get the halyard Classic symmetrical vs. asymmetrical! made before it fills. If you start jumping the spinnaker before your pointed low, it will probably fill before you get the halyard to the top (and your pitman will hate you because he has to grind the last 8 feet). As the spinnaker is being hoisted, pull the poll back aggressively so that when it fills your very square. You may want to leave the leeward twing on (if its really breezy) to stop the kite from rolling too far to windward when it fills. If coordinated well, the spinnaker should "pop" full only a second or two after the boat stands upright and is headed in the right direction. Light air gybing is often more difficult than heavy air gybing. Keeping the spinnaker full throughout the maneuver is paramount, and any mistakes seem to be amplified. Communication between the trimmer and helmsman is critical. The helmsman and trimmer should simultaneously turn the boat and begin to rotate the spinnaker at the same time. Even though this maneuver needs to be smooth, it can't be that slow. Once you bear away, your speed and apparent wind will drop out. The trimmer needs to ease the sheet fairly rapidly (don't smoke it) right to the headstay, while Steep n' Deep. taking up the new sheet at a similar pace. When the pole gets attached to new side it should move the clew back off the headstay by a foot or so. Hold the main until just after the stern is fully through the wind. This is also a good time to implement the "roll gybe". Leave as many crew members on the windward side as possible so that when the boat gybes the weight will now be to leeward and the boat will want to round up onto the new gybe. Your boat is now out of the gybe, hot on the other gybe, until you are ready to work it down again. Heavy air gybing is actually easier work for the trimmer. More often than not, because you are running very square, the trimmer simply needs to fly the spinnaker through the gybe by holding the two sheets stationary while the foredeck and pitman does their work. If you think about it, the boat never really has to change its direction by more than 20 or 25 degrees. Get the pole on the other side and then make your adjustments. If its really breezy, put some twing on and this will stabilize the spinnaker. It's always good to gybe when you can surf a wave. By increasing your boat speed, you take a bit of load off all the lines, especially the main sheet. It is ideal if you can pump the main into a surf and then into a gybe. By pumping the main, you will have it closer to the boat with no load on the sheet. Simply push it through the rest of the way while make your gybe The Perfect Gybe Gybing is one of the tasks that seems to present more problems than it ought to. Broken down it is simply another maneuver that needs to be treated in the same way as tacking . When we gybe we are changing tacks and setting up our sails on the other side of the boat. We are always trying to do this with minimum disruption and the least possible reduction in boat speed. Whatever size of boat we are sailing it is important to understand that the rate of the turn , the sails transferring sides and the crews mechanics must have a sequential order, and be timed correctly, for us to achieve the elusive perfect gybe. The perfect gybe will vary both in mechanics and aesthetics from boat to boat. Additionally whether we are using A-Sails (Asymmetrical Spinnakers) or S-Sails (Symmetrical Spinnakers) will have a large influence on the type of gybe performed. A further consideration is the size of boat that is being sailed. Smaller keelboats can change direction rapidly and have sails that can be trimmed and rotated quickly, larger heavy yachts require far more manpower, time and distance to gybe. S-Sail gybes in terms of the pole type principally fall in two categories dip-pole or end for end. As a rule of thumb dip pole systems are used on yachts longer than 38 feet with the end for end method being the norm on smaller yachts. As a basic explanation on the end for end gybe the pole is disconnected from the mast and spinnaker and passed through the fore triangle and reconnected on the other side. This system is often used with just sheets, but can be used with sheets and after guys. In the dip pole method the pole stays attached at the mast and is tripped from the after guy / brace and lowered to the bowman who clips the new brace into the pole end and sends it on its way out onto the new windward side.A-sail gybes on keelboats with moveable and fixed poles fall into two categories. Inside gybes and outside gybes. For an inside gybe the spinnaker changes sides by passing between the spinnaker luff and forestay. For an outside gybe the spinnaker passes around the outside of its own luff in an arc where the clew flies forward before being sheeted on the new side. A-sail gybes on keelboats with moveable and fixed poles fall into two categories. Inside gybes and outside gybes. For an inside gybe the spinnaker changes sides by passing between the spinnaker luff and forestay. For an outside gybe the spinnaker passes around the outside of its own luff in an arc where the clew flies forward before being sheeted on the new side. For any gybe to be a success a certain amount of preparation is needed. This might be in the form of boat preparation, but more likely best results will come from time spent refining each crew members contribution to the gybing procedure. On top of agreeing set roles and responsibilities for the maneuver their will need to be some set up tasks that are undertaken prior to gybing. For instance on a dip pole gybe, the bow team must have enough slack in the brace / afterguy to allow them to clip into the beak of the pole. The pole inboard end may need to be moved up the rig to allow it to pass through the fore triangle. The change of direction or angle that we need to turn through should be treated as preparation. If we are gybing through 60 degrees there will be a different amount of rotation or sheet on needed than if we are only gybing through 20 degrees. On many boats the gybing sequence will start with a call of “stand by to gybe,” this should put the crew on alert that a gybe may commence. Far to often the “stand by,” call results in a flurry of unstructured mayhem, which hinders the boats performance, and send panic through the crew meaning that when and if the call to proceed with the gybe is made it is regularly an unmitigated disaster. Remember the “stand by to gybe” call is exactly that. A call that alerts the crew. Following the “stand by” hail, the helm should clearly call “turning down” which initiates the maneuver. On this command the crew using an S-sail with a dip pole system will square the pole aft and start to rotate the spinnaker. In the pit the foreguy or downhaul must be eased to enable smooth pole movement. The bow team will have enough lazy brace on the bow ready to clip into the beak of the pole, they will also be holding the pole’s trip line ready to release the windward brace and to start the pole swinging from one side of the boat to the other. The call of &#x201Ctrip” triggers the spinnaker to be released from the pole and the main to start to be sheeted on start its transfer to the new side. To often the timing when gybing is hindered by no call being made. As well as the two functions mentioned several key moments are initiated by the trip call. At the call of trip the trimmers need to surge the brace forward a small amount ( 100mm on a Farr 40 is plenty) allowing the jaws of the pole to open without hindrance. Many people service their spinnaker poles after the pole fails to release when all that is needed is a momentary ease of pressure on the pole end to allow it to open. The rotation of the spinnaker will follow the pole release, setting the sail up perfectly for the angle that is to be sailed on the new gybe. The rate of turn should be married to the trimmers ability to rotate the spinnaker. Turning down to quickly in light air will result in too much apparent wind speed (AWS) being lost. Turning down too quickly in heavy air will not allow the trimmer to rotate the spinnaker quickly enough and will see a collapse of the sail on the new gybe. Obviously the lowering of the pole is key to ensuring a smooth transfer of the pole from one side to the other. However often overlooked in terms of the pole transfer is the effect that the rate of turn has on the pole swinging through. Get this right and everything happens smoothly. As the bow team clip the new brace into the pole a “made” call is needed which confirms the successful closing of the beak. Too often bowmen think this is a chance to test their vocal strength. A clear call is all that is needed, not a blood curdling war cry that distracts others from their task of getting every drop of speed from the boat that is possible. The “made call alerts the mastman and pitman that they are able to top the pole, taking care not to stab it through the foot or clew of the spinnaker. As the pole is passed through onto its new side the topper will be taken on hoisting the pole to its correct height. In all but the strongest of breezes I am a fan of flying the pole just a little lower after the gybe whilst accelerating the boat up to target speed. When gybing through less than 40 degrees the chute will need very little rotation. With this in mind, try to resist the temptation to ease the new windward sheet forward too much after the gybe. This will mean a longer wind for the brace trimmer / grinders but the benefits will be worthwhile. Once again the turn of the boat can be very influential here as can body weight movement. When the main is out on the new side and the pole is being re-topped a small bear away will allow the chute to fly to weather allowing the brace to be wound back far easier. Add to this some windward weight and the gybe is starting to take shape with kinetics as well as steering, mechanics and trim. Obviously there are key positions and tasks, which stand out in the gybe, however for the gybe to be a success there are some small ancillary tasks, which if performed at the correct time can have a major influence on the maneuver. For instance the twining lines / tweakers need to be controlled through the gybe especially the new weather side exited the gybe. As we turn down the leeward twinner can be pulled on. Ideally just as the pole is tripped. This moves the sheeting angle forward so that on the new gybe the spinnaker is not allowed to rise uncontrollably. The old windward twinner can be eased as the boat turns through dead downwind. Add to this an individual who is responsible for being a short term “human pole”. This crew member will immediately the main has crossed the boat, and hold the new windward side sheet that the sail is being flown on, forward and down. This augments what the twinner is doing and really helps the pole to be raised and squared back to its flying position at the clew of the spinnaker. I briefly mentioned kinetics and how they can be integrated into the gybe. Obviously on smaller boats the effect of moving crew weight will have a greater effect than on larger yachts where the crew weight is a smaller percentage of the all up weight. This does not mean that crew weight movement should be overlooked. If we integrate the crew movement in the form of a windward roll prior to gybing, we reduce the amount of helm needed to turn the boat and we start the spinnaker rotation to the new side. Experiment with your boat and how much roll works. Be careful in very light airs to not over roll the boat, as this will cause the chute to collapse prior to the gybe. The single biggest difference between an A-Sail and S-Sail gybe is that at some point in the A-Sail gybe it has to collapse as the air flow is switched from one side to the other. In the S-Sail gybe the flow changes direction but the sail remains set throughout as it can be set with either leech as the leading edge. This collapse of the sail needs to be kept to a minimum and the efforts to refill it on the new gybe should be a smooth and as structured as possible. The basic calls remain the same for the ASail gybe. The crew will need to transfer the sail from the pole to the bobstay / tackline prior to the turn. This will need communication between the pit and trimmers as the transfer is started, and then from the pit to helm indicating that the turn down can continue. As the boat turns down and the tack line is tensioned the sheet can be eased allowing the clew to travel forward. As this is happening the new sheet must be overhauled preventing any slack from dropping over the bow. Whilst this is happening the brace will have been eased forward allowing the sail to fly from the tack line and offering the bow crew a chance to remove the pole from the mast and the brace from the pole end. The control of the clew flying forward and rate of turn are married together ensuring that there is enough AWS to have the clew fly forward of the head stay so that the sail can be sheeted easily onto the new gybe. Obviously as the sail reverses around the head stay this is when the sheet need to be pulled on rapidly. Be careful not to over sheet the sail in your attempts to fill it. Once it has filled ease all the sheet you can allowing the sail to twist away from the boat. A tip in the light is to concentrate on your main and spinnaker trim to be perfectly married together with both sails moving in unison. As you exit a light weather A-sail gybe make sure the vang is eased and that the chute has clear exit or exhaust. If the main is over eased the slot will be choked and acceleration will be difficult. A little trick on exiting the gybe is for the trimmer and pit to communicate with regard to slightly easing the tack line as the sail sets on the new gybe. As the turn has created more AWS easing the tackline short term gives the sail a finer entry and allows the trimmer to ease more sheet for the speed build. At this time the bow crew will be placing the new brace into the pole and attaching the pole to the mast. As a rule of thumb it is worth considering the following guidelines. Sub 7 knots TWS (true wind speed) is inside gybing weather and above this should see outside gybes being used. On fixed poles the inside gybe will always be used. With regard to securing the brace and preventing it from dropping off the bow I like to use a preventer on the luff of the sail (see photo). This can be easily retro fitted and will make you’re A-Sail boat handling far easier. To summarize gybing should hold no fears and has to be treated as another chance on the racecourse to make gains. Always have a GYBING TECHNIQUES Rate of turn - Bad gybes are frequently the helmsperson's fault as they turn too fast and the spinnaker can't be rotated quickly enough (blows inside the headstay), or they turn too slowly and the spinnaker collapses (or wraps on the headstay). Allow the pole to be squared going into the gybe and for the slack in the new guy to be taken up before you head up on the new gybe. Get the MAIN in - In heavy air, it is critical that the main be trimmed most of the way in before you gybe. Otherwise, the helm will have to turn the boat TOO FAR to get the wind to help the main cross over. This will result in too fast a turn and too HOT an angle on the new gybe. The foredeck won't be able to get the pole on, and the trimmers won't be able to keep the chute full. Also, if you heel when on this too tight of a reach, you will BROACH...big ugly! Have 1-2 crew help the main trimmer jump the mainsheet in while on a run. When the main is most of the way in, the helm puts the wheel over. Call for the trip when the main flops across. This should be a RUN to RUN activity. Call the trip - The helm or skipper should loudly call for the trip. Do not call for a trip until you are sure the boat will gybe. In heavy air, make sure the main is in and WILL gybe before you call for the trip. ROTATE the chute - It is critical that the guy be squared as far as possible before the gybe. As the boat turns down, square back until the trip. Helm and "trip-caller" should wait for the guy to get back before the gybe. Full square keeps the chute from collapsing during the gybe and from blowing inside the headstay after the gybe. VERY CRITICAL on reach-to-reach and light air gybes. MAST MAN - Pole should be raised and lowered on the mast for each gybe. DON'T get lazy and keep it in the "ready to gybe" position. LIGHT AIR - In order to re-attach the apparent wind quickly on the new gybe, it is important to turn the boat through the gybe quickly and get up to a new HOT angle to fill the chute right away. This will require the pole to be fully squared going into the gybe and for the new sheet to be taken up and trimmed promptly. MARK LAZY GUYS - Each guy should be marked so that the trimmers can ease it to the mark, then load the drum and the bowman will have just enough slack to go forward to the pole. Watch the bowman and as soon as they yell "MADE", go nuts getting the slack in the guy taken up. You do not want to have extra slack to pull.