CONSTITUTIONAL LAW I

advertisement

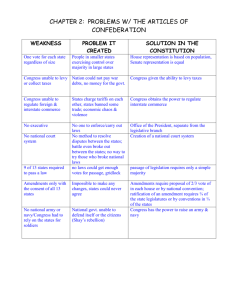

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW I Professor Beck: Jeffrey Kwastel PART 1: Fall 2001 THE JUDICIAL FUNCTION IN CONSTITUTIONAL CASES— THE NATURE AND SOURCES OF THE SUPREME COURT’S AUTHORITY. I. Introduction to the constitution. A) Articles of Confederation predececssor to Constitution Adopted in during the revolutionary war. Created 1 branch in the legislature which could create courts for dispute resolution only, appoint civil officers, or set up committees. B) Constitution set up to address inadequacies of the Articles. 1. Seperation of powers: 3 branches, with a bicameral legislature, an executive and a judicial branch. 2. For most things only need a majority of legislators to pass something, and there is a President who can veto it. 3. Selection of legislators (Article 1 §3). i. house by popular election, until 17th amendment, Senate was by state legislatur. Makes a difference how MCs elected; affects how federal government can regulate the states, and the states interest in maintaining its power from the federal government. ii. biggers states like Virginia were more powerful under the constitution, since under the Articles each state had an equal voice. 4. Constitution increases power of the federal government, but separates it. i. Articles §2 states that if a power wasn’t “expressly delegated” it didn’t exist, whereas 10th amendment of the Constitution omits “expressely” which could make a difference. 5. Specific issues on which Articles were viewed as inadequate: i. regulation of commerce: trade wars were erupting between the states. ii. there was nocentral government to enforce repayment of revolutionary war debts. iii. Rebellions, such as Shays, were difficult to put down. iv. Trouble dealing with foreign policy issues such as Britain maintaining forces in the northwestern forts, and Spain not letting us send commerce all the way down the Missippii. II. Judicial Review A) Legetimacy of Judicial Review: Marbury v. Madison. 1. Constitution: although there is no specific provision for judicial review, the Constitution creates an independent judiciary with power equal to the other 2 departments. Article III creates the Supreme Court and extends the judicial power to “all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made…under their authority.” The judiciary was thus responsible to decide cases, using the Consittution as the Supreme Law. 2. Facts: Marbury appointed as a jp for DC by President Adams and confirmed by the Senate on Adam’s last day in office. Their formal commissions were signed but not delivered. Madison, , as Secretary of State, was directed by the new President (Jefferson) to withhold ’s commission. brought a writ of mandamus directly to the Supreme Court under the Judiciary Act of 1789 which established United States courts and authorized the Supreme Court to issue writs of mandamus to public officers. There are issues over whether Marshall should have recused himself from the case. Marshall held that the act was unconstitutional because the court only had appellate jurisdiction over this matter and needed original jurisdiction in order to grant the writ. 3. Marshall’s reasoning: Branches affect each other, ex: Congress creates a legal duty by saying someone can pay 10 cents for a copy of a public record. There are situations where the only considerations that govern the conduct of executive officers are political. However, there are other situations where the executive has clear legal duties that affect individual rights. Here, Marshall says that the jurisicdictional statute was unconstitutional. Courts will try to construe a statute to avoid a serious constitutional question but if a law is repugnant to the constitution than it is void. The constitution creates boundaries, but need an umpire to say when going outside those bounds; that is the role of the Supreme Court. 4. Marshall says that the Constitution supports judicial review: i. Supremecy Clause, Article VI: “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” Doesn’t directly talk about judicial review (even seems to be directed to state judges). But it does recognize that (at least some set of) judges are supposed to be looking to the constitution in order to make their decisions. ii. Article III, §2: sets forth the judicial power. Marshall says it shows that the framers intended the courts to look at cases arising under the Constitution. iii. Constitution already gives instructions on how to resolve cases: Ex: rules of evidence for treason, prohibition on ex post facto laws, etc. So if there is a clear case where Congress has said to do one of these things and the Constitution says not to, he doesn’t understand how someone could do it. 4. Should Marshall have avoided ruling on judicial review? i. B) Could have said that the commission wasn’t effective until delivered (instead concludes that even without delivery Marbury had a vested legal right to the commission). Repercussions of constitutional interpretations: 1. Jefferson: no one has exclusive control over constitutional interpretation. In a letter to Abigal Adams re: his pardons of persons prosecuted under the Sedition Acts (and regusal to further enforce the act), he states he felt the act was unconstitutional. Each branch has to uphold the constitution, no one has exclusive power over its interpretation. 2. Can read the Marbury decision broadly or narrowly: i. Narrow interpretation: Marshall wasn’t claiming any special role for the court, just ruling on the facts of this case. ii. Broad interpretation: page 9, paragraph 4, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” 3. More recently, the Court has asserted a broad judicial power, claiming the responsibility of being the ultimate interpreter of the Constitution. i. Cooper v. Aaron: Initial TC decision that schools had to be desegregated. State officials then claimed they weren’t bound to the decision because they weren’t party to the original suit. The Court responds (top of page 25), interpreting Marbury; “This decision declared the basic principle that the federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the law of the Constititution, and that principle has ever since been respected. Constititution is the supreme law of the land, and we are the supreme interpreters of that law, therefore our decisions are the supreme law of the land. 4. Potential problems i. Potential problem 1: Ex: Rehnquist by a 5-4 decision says he’s the commander in chief of the armed forces. Are their decisions the supreme law of the land? ii. Potential problem 2, argument that judicial review isn’t compatable with democratic government. Judges are appointed rather than elected, they have life appointments (unless impeached), and their compensation can’t be reduced once they have been appointed. Hamilton counters that argument by saying that they’re implementing the will of the people as expressed in the constitution (even more so thatn in legislation). ii. Judges could be drive by political considerations: Hamilton says courts least dangerous of the branches since they “have neither force, nor will, only judgment.” 5. Authoritativness of Supreme Court decisions. Article III, §2 defines judicial power: extends it to certain cases. Supreme Court has appellate jurisdiction over the highest state courts on issues involving federal Constitution, laws, and treaties. III. i. Ex: Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee. was heir to the VA estates of Lord Fairfax who died in England. VA claimed title to the estates in 1777 through state legislation confiscating the property of British loyalists; it had conveyed title to Hunter. Lessee, , lessee brought an action of ejectment. defended title by virtue of US-British treaties protecting such property. VA Court of Appeals sustained ’s claim, but was reversed by US Supreme Court. Court ruled that VA court must obey its rulings. ii. All cases involving the Constitution, laws and treaties of US are included in the judicial power granted to the Court; hence all such cases are properly subject to that Court’s appellate jurisdiction, and §25 of the Judiciary Act is valid. Such power is necessary for a uniformity of decisions through out the whole US and upon subjects under the purview of the constitution. The Nonjusticiability of Political Questions 1. The requirement of a justiciable Article III controversy is deemed to carry with it a limitation against the deciding of purely “political questions.” The Court will leave the resolution of such political questions to the other departments of government. Primary criteria in making this determination are: i. A “textually demonstrable” constitutional commitment of the issue to the political branches for resolution. ii. The appropriateness of attributing finality to the action of the political branches. iii. The lack of adequate standards for judicial resolution of the issue. iv. Avoidance of issues that are too controversial or could involve enforcement problems. 2. Court isn’t going to review discressionary decisions. i. Court needs standards for being able to make a decision. Ex: Luther v. Borden. RI has 2 governments claiming power. s admit they were trespassing, but say not liable because acting as government agents to prevent participation in an election run by the other government. says Charter government illegal because Article IV, §4, Guarantee Clause (guarantees form of republican government). Court says that whether a state has a Republican form of government under this clause isn’t something they are going to determine. Congress’s decision, whatever they did would cause chaos. Decision also brings up prudential limitations. ii. The fact that a suit seeks protection of a political right does not mean it necessarily present a political question. Doctrine is of political questions, not political cases. Ex: Baker v. Carr. TN basing apportionment on 1901 census in 1962, so some representatives had more people than others, but all had the same vote. Court held that federal courts posses jurisidiction over a challenge to a legislative apportionment: mere fact that a seeks protection of a political right does not mean a political question is presented. The issue here is whether the state’s activity is consistent with the federal constitution; case remanded. 3. Court can resolve issues related to actions of other branches: won’t read so broadly that all issues become political questions. i. Ex: Powell v. McCormack. House refused to seat , alleges he had previously committed corrupt acts. Cite Article I, §2, clause 2. Each house will be the judge of its own members. But the Court says that doesn’t mean they can set new qualifications, just judge those already set out in the Constitution. It’s otherwise up to the voters to decide if they want someone. ii. Foreign affairs: concern comes up a lot. There are textual commitments to other branches (ex: make and enforce treaties, make war), a lack of standards (descisions are discretionary), and a respect of coordinate branches. 4. Political question since Baker v. Carr. i. Goldwater v. Carter: President Carter wants to terminate a treaty with Taiwan. The Constitution under Article II, §2 gives the President the power to make treates with concurrence of 2/3 of Senate, but is stilent on how to get out of them. A plurality decided the case was nonjusticiable; argument that President has unilateral power in this area. Since the Constitution gives him the power to make treaties there is implicit power to terminate them. However, the argument for Senate power in this area is that Article VI, para 2; is it relevant that treaties are law (President doesn’t have the power to end other laws). ii. Ex: Nixon v. US. Nixon was a federal judge who was subject to impeachment. His complaint was that his trial was held before a committee (which then made a recommendation before the body to vote) instead of the entire body. But, an action is nonjusticiable where there is a textually demonstrable constitutional commitment of the issue to a coordinate branch of government or a lack of jusicially manageable standards for resolving it. The Court decides that the word “try” does not require a judicial trial, and is not an implied limitation. Judicial review of the Senate’s trying of impeachment would be inconsistent with the system of checks and balances. Impeachment is the only check on the judicial branch by the legislature, and it would be consistent to give the judicial branch final reviewing authority over the legislature’s use of the impeachment process. IV. Political Restraints on the Supreme Court: May Congress Strip The Court Of Its Jurisdiction? A) Article III, §2, Clause 2: gives Congress the power to regulate and limit the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court at any time and at any stage of proceedings. Congress may withdraw particular classes of cases from the Court’s appellate review. B) Withdrawl of jurisdiction during consideration of a case: 1. Supreme Court’s jurisdiction is conferred by the Constitution subject to such exceptions and under such regulations as Congress shall make. Without jurisdiction, the Court cannot proceed to consider the case. 2. Ex: Ex Parte McCardle newspaper publisher taken into custody for publishing “incendiary” articles, he appeals for habeus corpus relief. Appealed to the Court pursuant to an 1867 Act. After a hearing, but before the final decision, Congress repealed the portions of the Act that permitted the appeal. The Court held that Congress could negate previously granted jurisdiction of matter brought to the Supreme Court based on that jurisdiction. C) Congressional action cannot interfere with autotomy of another branch 1. US v. Klein i. Citizens were trying to get reimbursed for poperty seized during Civil War. Statute required they rpove they were not one of those who rebelled against the US. Court agreed that a pardon showed you were not a rebel, but Congress passed a statute saying the opposite. ii. Interference with judicial and executive autotomy. Court held that statute to be unconstitutional. It was an attempt to deny the effect of pardons and to prescribe rules of decision to the judicial department to pending cases before it. Also denied effect to presidential partdons. iii. Congress can still amend the law even if it will affect the outcome of a pending case. 2. Plaut v. Spendthrift Farm: violation of seperation of powers. D) i. Congress can’t retroactively change the statute of limitations. Court had said the statute of limitations expired, Congress went back and tried to reopen them. Can’t reopen a case that’s already been decided by the Court. ii. Hart said Congress could not interfere with the central and core functions of the Supreme Court—can’t interfere with finality. Modern attempts to limit the Court’s jurisdiction 1. Generally: Legislation to limit the Court’s jurisdiction has been introduced in response to particularly controversial decisions, eg Miranda, school prayer, and abortion. To date, these proposals have not succeded. 2. Limitation on successive habeus corpus petitions: Felker v. Turpin i. E) Court considered whether Congress unconstitutionally limited the Court’s appellate jurisdiction by enacting legislation that curtailed state prisoner’s successive applications for federal habeus corpus relift. The Act precluded the Supreme Court review of courts of appeals’s decisions granting or denying the right to file a second or successive petition. Since a petitioner could still file an “original” peitition (one that is filed for the first time in the Supreme Court), Congress has not deprived the Court of appellate jurisdiction under Article III, §2. For constitutional purposes, consideration of these “original” petitions involves exercise of the Court’s appellate jurisdiction. Checks on the Court other than impeachment 1. Number of justices: not in Constitution. Congress has decided in principle this isn’t something they should do. 2. Appointment process (advice and consent): Try to predict how judges will rule. Tends to be inaccurate (ex: Souter much more liberal than thought), they have life tenure, and don’t know what the hot button issues will be down the road. 3. Control when they meet: Court didn’t meet one year because Congress repealed it’s term. 4. Constitutional amendment: Article V. V. Case or Controversy Requirements: Advisory Opinions, Standing, Mootness and Ripeness. A) Standing Doctrine: 1. Articulates who and when someone can bring a claim and what kind of claim they can bring. i. Used by courts to limit their own power. ii. Article III, §2: defines Court’s power. Constitution talks about case and controversy. iii. Ex: Marbury v. Madison. There was an injury-in-fact since hadn’t received his commission yet (couldn’t get paid). Causation since Madisdon wouldn’t hand over the commissions. Redressibility since the relief requested would address the injury. 2. Purpose of standing rules: i. preserves separation of powers, limiting the role of the Courts (prevents them from serving a broader more political function). ii. promotes better decision-making. The emphasis is on concrete disputes between adverse parties, has a narrowing effect. iii. Promotes vigorous advocacy, makes certain that the parties have a stake in the outcome. People won’t start a lawsuit unless they have a real stake in the issue. iv. Might want to reduce number of cases in the federal system. v. Close courts to officious meddlers (although could recruit an injured person to an association). vi. Court wants to avoid resolving Consititutional questions (in part because of stare decisis). B) Constitutional v. prudential limitations: Court has drawn distinction between Constitutional limitations and prudential limitations (rules they think are good) on standing. If it comes from the constitution Congress can’t do anything about it. But Congress can override provincial limiations. 3 general requirements of standing set out in Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife: 1. Must be an injury in fact: concerete, particularized, actual, or imminent (not hypothetical). i. Ex: McCardle, was in jail under what he thought was an unconstitutional statute. But in Lujan its an organization suing, which is okay if it can show that it, or its members (which would be the basis if the member brough suit), suffered an injury. ii. 3 part test for associational standing: 1) injury to members, 2) germane to organization’s purpose, and 3) no participation required by individual members. Ex: in Marbury v. Madison, it John Adams society, dedicated to getting as many federalists onto the bench as possible, sued (without Marbury as a member) there would be an injury but it would be a generalized grievance. iii. Organization’s basis was the reinterpretation of the Endangered Species Act to now apply in this country instead of overseas as well. Organization’s basis for claim of standing was that it had members who wanted to go overseas and see the animals. Court says that could possibly give rise to an injury in federal court, but not here because it’s not definite (can’t claim that the regulations prevented them from seeing anything now, its if they might go back). iv. Can’t be a 3rd party injury: ex: Marbury v. Madison. Marbury promised a recent GW law grad a clerkship. That guy can’t sue to get Marbury the job. 2. Injury must be particularized: Prudential challenge, not constitutional (so it could be challenged). Doesn’t work in Lujan because the injury is a general grievance, and the Court says it doesn’t entertain those. i. Court suggests that there is a seperation of powers issue: Congress would be transferring power to executve laws from the president to the courts. Every executive branch decision would become reviewable in court. ii. Ex: Frothingham v. Mellon, taxpayer tried to keep Secretary of Treasury from making grants to states to reduce infant mortality, but “I’m injured as a taxpayer” is not enough to give standing, the injury is shared by all taxpayers. iii. Ex: Scheslinger v. Committee to stop the war. Injury suffered by these s is no different than the others. iv. Ex: FEC v. Aikns. FEC decided AIPC wasn’t a political committee. wanted to know about AIPC’s membershup since that would affect how they vote. Court says this injury is different than generalized grievances, specific injuries. 3. Injury must be redressible by the courts. In Lujan, Court said that they could only get redress against the secretary, but that change in the regulations wouldn’t address the injury—there was no gurantee the species would rebound even if the regulation is withdrawn. C) Mootness and non-ripeness 1. The usual rule in federal cases is that an actual controversy must exist at all stages of appellate or certiorari review, and not simply at the date the action is initiated. i. Exception: cases that are capable of repetition yet evading review. Ex: Roe v. Wade. Person already had the baby, otherwise wouldn’t be able to be reviewed in time to be addressed. ii. Ripeness: the Court will only decide those issues that are “ripe” for adjudication. It will not anticipate a question of constitutional law prior to the necessity of deciding it or pass upon issues that may nor may not arise sometime in the future. Ex: United Public Workers v. Mitchell. challenged Hatch Act (which said that federal employees couldn’t participate in campighns). Court said case was brought too early since no one had tried to participate in any campigns. iii. PART 2: A) Advisory opinions: Court generally won’t give them. NATIONAL POWERS AND LOCAL ACTIVITIES: ORIGINS AND RECURRENT THEMES Introduction: 1. Legislative Power: Article I, §1 lodges all legislative power in Congress. This is the power to make laws and to do all things which are necessary to enact them (such as to conduct investigations and hold hearings, etc.). 2. Delegated Powers: The powers of Congress are specifically enumerated. In other words, the federal government in one of delegated powers only, and every federal statute, therefore, must have as its basis one of these enumerated powers. B) The Necessary and Proper Clause—McCulloh v. Maryland. 1. The specific powers of Congress may be enlarged by the necessary and proper clause. 2. Facts: McCulloch v. Maryland. Maryland sought to enforce one of its statutes, which imposed a tax on banks operating within the state but not chartered by the state, against the Bank of the United States and McCulloch (), its cashier in Baltimore. The statute in question was similar to others passed in other states during a period of strong state sentiment against the Bank. had refused to pay the tax; penalties imposed as a result were affirmed by the Maryland Court of Appeals. 3. Issues 1: Does the constitution grant Congress the power to incorporate a bank? Not expressly, but has the implied power to do so. Under the Articles of Confederation there were no implied powers (just what was expressely mentioned in the document). Chief Justice Marshall says the framers were careful to leave that restriction out of the constitution. i. Constitution is a broad outline, not a legal code. ii. Marshall says Congress is given the choice of means by which to accomplish its ends. Assume framers weren’t trying to restrict powers unless they say otherwise. iii. Marshall rejects Maryland’s argument that “necessary and proper” means “indispensable” If took that view, could we maintain a Navy or have internal improvements? Marshall says that necessary can have different degrees (allows for discression), and when the framers wanted absolutely necessary they said that. iv. Means-end relationship: Framers intended for there to be a choice of means to reach the ends stated in the constitution, Article I, §8. Ex: Marshall talks about the mail: there is no express grant of power to punish those who steal the mail, but in order to carry out that purpose have to read the constitution to allow it. There are restrictions already in the constitution (ex: Congress can’t pass ex-post-facto laws). v. Test: (page 95) let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end…are constitutional. vi. Whose intent matters: framers? Compare to a k; drafted by an attorney but given legal effect by the parties, suggests ratifiers intent should control. It’s a debate that’s being interpreted. 4. Issue 2: the federal government is supreme over the states so that a bank created by it pursuant to its constitutional powers is immune from taxation by the states. C) i. The Constitution and the laws made in pursuance thereof are supreme. They control the constitutions and laws of the respective states and cannot be controlled by them. The power to tax is the power to destroy, and here Maryland is trying to control an operation of the whole government of the US. ii. When a state is taxing its own citizens, its not particularly dangerous because those citizens can vote for the legislators (which prevents them from acting abusively). That protection is not available here. Here, the national bank is for people throughout the country and most of those people don’t vote in Maryland elections. If we let states exercise this power of taxation it would thwart the power of Congress to carry out its ends. Federal Limits on the Scope of State Power—US Term Limits Inc. v. Thorton. 1. 10th amendment only reserves to the states powers they already had. 2. Facts: Ark adopted a constitutional amendment that prohibits the name of an otherwise-eligible candidate for Congress from appearing on the general election ballot if that candidate had already served three terms in the Hosue or two terms in the Senate. The amendment was formulated as a ballot access restriction rather than as an outright disqualification for membership in Congress. US Term Limits Inc () challenged the amendment. The Arkansas Supreme Court held that the amendment violated the federal Constitution. The Court grants cert and then decides its unconstitutional. 3. A state may not impose qualifications for membership in Congress in addition to those provided for in the federal constitution. i. Majority looks to the qualification clauses, Article I, §2 (House) and §3 (Senate) and reads those requirements as being exclusive. ii. Dissent points out that Article I, §4 gives states power over time, place manner of holding elections. Could argue that AK law is a reg of that type, that the constitution doesn’t specifically address the issue. iii. History: Both the majority and the dissent discuss history. Majority says that after Constitution majority of states chose not to adopt property qualifications for members of Congress, dissent says they were falling out of favor and shouldn’t draw conclusions from silence. iv. Reserved powers: Dissent says people should be allowed to chose who to represent them, even in this way, because any power not delegated to the US or prohibited to the states is reserved to the people. The majority says that the reserved powers are what existed before the constitution (states keep those with some modifications), this power was not amongst them. 4. States set voter qualifications with some limitations. 5. Whose intentions matter on these issues?: i. PART 3: A) people who voted in ratifying constitution had very different intents, might be hard to understand the thought process of people who lived in 1789; philosophy called “originalism”—what would they have thought if they know what we know now? THE COMMERCE POWER Interpretation of the commerce power from 1824 to 1936 1. Article I, §8: “The Congress shall have the power to…regulate commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian Tribes.” 2. Early view: Gibbons v. Ogden. i. Facts: NY legislature gave monopoly to operate steamboats to Livingston and Fulton. Ogden has a license from L and F. Congress then enacts a law saying need a license for that trade. Ogden competitor, Gibbons, started operating a business with a license pursuant to that law. Ogden obtains an injunction in NY courts telling G not to operate in NY waters. G ultimately prevails: prevents enforcement of NY monopoly on supremecy clause—federal law takes precedence over NYS law. ii. Court gives early defintion of commerce: Marshall says that commerce among the states is commerce intermingled with the states. Congress has some power past the border to regulate in the interior, but the limitation is that it must concern more than just one state. Marshall rejects O’s contention that navigation is not commerce. 3. Manufacturing v. Transportation: United States v. EC Knight (1895). A federal antitrust prosecution under the Sherman Act, trying to set aside the merger of sugar companies that controlled 98% of United States sugar refining. The Supreme Court defined federal power by defining the scope of the words “commerce” and “interstate.” The Court essentially limited interstate commerce to transportation across state lines (thus narrowing the position taken by the Court in Gibbons), holding that “manufacturing” and “production” were not interstate commerce. Manufacturing is the transformation of raw materials, commerce is the transportation of what is made. Things like farming and mining take place before commerce. While this holding didn’t halt antitrust enforcement (Addyston Pipe and Steel v. US—although that case may not actually be different), it was later used to block New Deal legislation. i. Court also says that effects have to be direct, here they are indirect—can’t regulate indirect effects.. ii. described as formalistic reasoning: setting up categories and classifying acitivties based on where they fall. 4. Substantial economic effects approach: Shreveport Rate Case. Sustained Congressional authority to reach intrastate rail rates that discriminated against interstate rail road traffic. Rail lines crossed state borders. ICC regulated the rates of railroad traffic between TX and LA, but the ICC charged more than for much longer intrastate TX routes. ICC wants to regulate TX rates as well. i. Whenever the interstate and intrastate transactions of carriers are so related that the government of the one involves the control of the other, it is Congress and not the state, that is entitled to prescribe the final and dominant rule. 5. The Stream of Commerce Theory: Stafford v. Wallace (1922, page 168). Stockyards, whre many cows will eventually be sold across state lines, was determined to be within congressional regulatory power. B) i. The stockyard is within the stream of interstate commerce. ii. Current of commerce is a typical, constantly recurring course, the current this existing is a current of commerce among the states. Prohibition of Interstate Commerce as a “police” Tool 1. Regulatory power includes prohibition of commerce: i. Champion v. Ames (the Lottery case). Congress prevented interstate shipment of lottery tickets. Called it a “commerce prohibiting technique”, builds a barrier by not allowing the tickets to cross state lines. Not an economic regulation: primarily a moral issue for Congress was protecting the people against the widespread pestilence of lottery tickets. ii. Hipolite Egg Co. v. US: Court says that the power to seize is necessary as an appropriate means to the end of preventing interstate commerce of adulterated products. Eggs were confiscated under the Food & Drug Act because there wasn’t a label which was required for certain ingredients. Federal government wants to seize the eggs even though they have already reached their destination. Brings in McCulloh, necessary and proper clause, regulating in terms of means-ends relationships. Article I, §8 gives power to regulate commerce, so need power to regulate shipment and to seize goods to carry that into execution. 2. Limit on police power: Hammer v. Dagenhart. Congressional law trying to prevent products created by child labor from crossing state lines. Another case under the commerce prohibiting technique. Again, acting for noncommercial or non-economic reasons. Trying to prevent goods from crossing state lines to effectuate that goal. Court decides that this case exceeds the commerce power. i. In Lottery, the product was the problem, but here, the items being shipped across state lines are not harmful. Harmful effect takes place in the manufacturing stage (local matter). ii. Holmes dissents that the only issue is whether they are exercising a power given to them by the constitution, can’t look to the purpose. 3. Relationship or nexus to interstate commerce: Railroad Retirement Board v. Alton (1935). Act established a compulsory retirement and pension plan for all carriers subject to the Interstate Commerce Act. The argument was that such a plan was necessary to the morale of the workers, and that this moral effected efficency, which in turn affected interstate commerce. The Court held that the relationship of such legislation to interstate commerce was too remote. i. Distinguished from Shreveport Rate Case because that was regulating commercial activities (charges), but this is a further step removed because it is trying to regulate labor activities. 4. The “indirect effect” theory: Schechter Poultry Corp v. US (1935)—aka “The Sick Chicken Case.” The Court ruled that Congress odes not have power to extend the regulation of interstate commerce to intrastate activities that have only an “indreict effect” on interstate commerce. i. This code created wage and hour requirementsfor the poultry market in the metro NY area. Also required that you could not force them to buy the whole coop, including the sick chickens. Schechter was convicted of violating the code; he was not an interstate seller of chickens. Got his chickens from people who got them from out of state; he prepared them for further sale to local dealers, so he purchased and sold in NY. ii. Court decided this regulation was unconstitutional because the act unconstitutionally delegated powers and the application of the act to intrastate activities exceeded the commerce power. Said the stream of commerce ended with Schechter since he only made intrastate sales. His activities have only an indirect effect on interstate commerce; thus allowing this would open the door too widely (anything could be regulated). 5. Federal power over production of goods: Carter v. Carter Coal Co. (1936). Bitumnious Coal Conversation Act set wage and hour regulations in coal industry. Violations imposed a penalty tax. The statute sets a bsis for Congressioanl regulation that the court rejects. Idea was that since this affects the whole nation, Congress has the power to regulate it (good for the general welfare). Court does not regulate this power. Congress has only powers in the constitution. Court then looks to the commerce clause. i. Draws a distinction between production and commerce, and decides this is on the production side. ii. Still an indirect effect: In Schecter they talked about the effect on price, here they discuss the effect on labor unrest. If there is a strike, interstate commerce could be shut off completely. Court holds that indirect effects cannot be regulated even if they have a dramatic effect. iii. Under this direct/indirect test an activity that took place entirely within a single state may be regulated by Congress if its effect is a direct one. This test allows Congress to be subjective in its choice about whether to uphold legislation. C) The Decline of Limits On the Commerce Power From 1937 to 1995. 1. Justice Roberts suddenly starts voting the other way, perhaps to avoid Court packing plans. 2. Switch to “Affectation Doctrine”: NLRB v. Jones and Laughlin Steel Co. Court abandoned the geographical (eg manufacturing is local) and “direct v. indirect” concepts. The Court’s position now is that Congress has the power to regulate any activity, whether it be interstate or intrastate in nature, as long as it has any appreciable effect whatever on interstate commerce. i. discharged employees in violation of the NLRB. 4th largest steel company in the US, involved a lot of interstate activity. Labor strife could conveitably cripple the entire interstate operation of the company, thus interstate commerce was affected and Congress may regulate ’s activity. ii. Congress can protect interstate commerce from dangers, even if they are local in nature. 3. Bootstrapping technique (regulating by prohibiting commerce): US v. Darby (1941). Congress can establish and enforce wage and hour standards for the manufacture of goods for interstate commerce. i. 2 sections of FLSA at issue, court said Congress could ban interstate shipment of goods made in violation of wage and hour laws, therefore okay to regulate those wages and hours. The regulation of wages and hours is a means towards effecting a ends. 4. Aggregation of local activities: Wickard v. Filburn (1942). Court turns to a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce test to determine scope of the commerce clause. i. Farm production which is intended for home consumption is subject to Congress’ commerce power, since it may have a substantial economic effect in interstate commerce. Dairy farmer was penalized for producing excess wheat under the Agriculture Adjustment Act. Using excess primarily for his own farm. ii. While Filburn’s overproduction of wheat might have been trivial, need to apply an aggregation technique to see if Congress can regulate the class of activity. 5. Congress can basically regulate anything: Using aggregation i. Hodell Congress regulated strip mining for environmental purposes. Act is challenged by coal miners as exceeding powers under commerce clause. In aggregate has subsntaitla economic effects. Companies that comply are at a competitive disadvantage to those who don’t. Under thie test could probably regulate marriage and divorce and law school admissions (aggregate ecnomic effect of all those people sitting in chairs). ii. Heart of Atlanta Motel v. US. Title 2 prevents discrimination in places of public accommodation (ex hotels, restaurants, places of entertainment). Here there was a motel that discriminated against Africa-Americans from staying there (didn’t put more weight into 14th since that only effects state actos). Court used aggregation theory to find that discrimination has a substantial harmful effect on interstate commerce: discourages travel by African-Americans, etc. Congress can act under commerce clause even if trying to achieve moral rather than economic ends. 1. Congress has increasingly relied on the commerce power to enact criminal laws. The Court has generally upheld this use of the Commerce Clause. Evne though the criminal transaction might be purely intrastate, it might affect interstate commerce if it provides revenue for, eg, organized crime. D) i. Ex: Perez v. US. Congress was able to enforce loan sharking statutes. Congress was able to sue the commerce power to define and regulate a class of activity that might include individual acts unconnceted with interstate commerce. ii. Congress ays these acticities cause takeovers by racketeers of legitimate businesses. Court probably going to be deferential to these findings. iii. Where the class of activities is regulated and that class isn properly within the reach of federal power, the courts have no power to excise, as trivila, individal instances of the class, whether o nit they occur soley within one state. New Limits on the Commerce Power Since 1995. 1. Court has recognized that there are still limits on commerce power. Ex: US v. Lopez. charged under 1990 Federal Gun-Free School Zone Act. Court rules it exceeds Congress’s regulatory powers. Act made it a federal offense for any individual to knowingly posses a firearm at a place that is a school zone (have to make a showing that the gun was moved in interstate commerce). i. There are 3 broad categories of activity that come within Congress’s commerce power: 1) Congress may regulate the use of channels of interstate commerce (Darby wage regulation, can’t ship products made in violation); 2) Congress may regulate and protect the instrumentalities of interstate commerce, as well as persons or things interstate commerce (Shreveport Rate Case); and 3) Congress can regulate activities that have a substantial relation to interstate commerce, meaning those that substantially affect interstate commerce. ii. Act here is a criminal statute that has nothing to do with commerce. Possessing a gun in a school zone does not arise out of a commercial transaction that substantially affects interstate commerce. Neither does the Act contain a requirement that the possession be connected in any way to interstate commerce. Majority rejects dissents chain of reasoning (saying there is a substantial economic effect and only need to see that congress had a rational basis for deciding on this measure), saying that anything could then be regulated as commercial. iii. Majority discsses that education is a traditional state function. Ex: US v. Bass, Court, dealing with a statute that goes into a traditionally state area of concern, says they’re going to narrowly construe statutes in certain circumstances 2. Congress can regulate effects on interstate commerce, but doesn’t have a general police power. i. Thomas in concurrence in Lopez is concerned with substantial effects doctrine: Congress has enumerated powers, wouldn’t need those provisions if they were meant to have such broad powers. ii. US v. Morrison, Violence against Women Act, created a federal coa for someone who was a victim of gender motivated violence; doesn’t say it has to be while engaged in interstate commerce. If this act fit anywhere, it would be the third category of Lopez, except that the activity being regulated is not economic or commercial. Court looked at Congressional findings that gender motivated violence put women out of the work place and decreased productivity. The Court here was trying to place boundaries around the commerce power to maintain that the federal government only has specified powers, not a general police power. iii. Court still using a rationale basis test, so how much has changed? Breyer’s dissent in Morrison—A lot of the effects on interstate commerce in Lopez and Morrison are similar to Ollie, Heart and others done under Title 2 of the Civil Rights Act. PART 4: FEDERAL LIMITS ON STATE POWER TO REGULATE THE NATIONAL ECONOMY I. External Limits on the Commerce Power: State Autonomy, Federalism, and the Tenth and Eleventh Amendments. A) Extent to which Congress can regulate local or state conduct under commerce clause B) i. Coyle v. OK: Court said couldn’t tell a state where to locate its capital. ii. US v. CA: Congress could impose safety standard on local railroad. iii. NY v. US: state owns spring and Congress could tax that water. iv. Fry v. US: wages of state employees could be regulated by Congress. 10th amendment limits on federal regulation under commerce clause 1. “The Powers not delegated to the US by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States, respectively, or to the people.” 2. Congress cannot impermissibly interfere with integral government functions of the states—National League of Cities v. Usery (1976) [since overruled] Using FLSA, Congress extended minimum wage and hour laws to all state employees. Court said that was unconstitutional because can’t interfere with employee relationships in traditional state governmental functions. 3. Court is concerned about maintaining traditional state functions 4. i. National Legaue of Cities, Court discusses how States might otherwise set up their compensation schemes differently. Court is concerned about preserving traditional state functions (ex police, sanitation, fire fighters). ii. United Transportation Union v. LIRR, Court decides that owning a rail road was not a traditional state function, so is distinguished from United Transportation. Therefore, there is no interference with traditional state functions here. National League gets qualified to death: i. EEOC v Wyoming: Congress trying to apply age discrimination statute to employees. Court allows Congress to regulate, says degree of intrusion ii. isn’t as great as National League (although could actually say that’s more intrusive). FERC v. Missippii: Trying to get utility companies to adopt certain regulatory standards. Don’t have to adopt, just consider. Court permits this mandatory consideration on the grounds that Congress could have preempted the field entirely, so should invalidate the field entirely because Congress adopted a less intrusive scheme. 5. Renewed supremecy of federal government: National League overruled by Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority. i. Attempt to subject transit authority to FLSA. ii. Court decides that traditional governmental functions category doesn’t work because then have judges, who aren’t elected, making those decisions. iii. Blackum suggests that states don’t need the Court to look out for them here, since they have access to the political system (lobbying, redisreciting, etc). 6. Limits on congressional regulatory authority: New York v. United States. i. Congress addressing problem of dumping radioactive waste, no one wants to set up these disposal sites. They are trying to encourage states to create these sites or enter into a regional compact. The statute 1) gave permission to put a surchage on out of state waste which was put into escrow, 2) authorized the states to gradually increase the cost of access to the sites and then to deny access altogether to those that don’t meet federal guidelines, and 3) gives the option of forcing states or cooperatives that can’t dispose of the waste to take title and possession of radioactive waste they generate. ii. 3rd provision is unconstitutional: this measure commandeers states for federal purposes, taking control of their decision making process. Compelling states to act, versus giving them incentives, undermines political accountability (want to prevent Congress from hiding behind state governments to make unpopular decisions). iii. Also, can’t allow states to discriminate against each other, which this provision does. 7. Congress does not have the power to commandeer local officials: Printz v. US. i. Provision of Brady handgun bill at issue. As a temporary measure the Chief Law Enforcement Officer (CLEO) for an area was supposed to run a background check. ii. Majority says that, like in NY where couldn’t commandeer state legislatures, here can’t commandeer state executives. Reject notion that Congress was to have this power (even though can create a federal coa in state court and state judges are bound by federal law). There is, like NY, an issue of accountability: local official is the one who is going to be blamed for enforcement of this federal law. iii. This ruling in reconciled with Garcia by saying that Congress can include states when it’s a generally applicable statute. 8. Congress can still regulate things in interstate commerce, even when the seller is a state: Reno v. Condon. i. Congress said that when apply for a driver’s license, states can’t sell the data they collect. ii. Fits into the second Lopez category of regulating things in interstate commerce. The case is directed to the state as an owner of the database, so the fact that is a government is irrelevant. iii. DPPA was generally applicable: regulated everyone who supplied these things (although Court did not address the question of whether general applicability is a constitutional requirement for federal regulation of the states). PART 5: THE POST-CIVIL WAR AMENDMENTS AND CIVIL RIGHTS LEGISLATION: CONSTITUTIONAL RESTRAINTS ON PRIVATE CONDUCT: CONGRESSIONAL POWER TO IMPLEMENT THE AMENDMENTS. I. Congressional Power to Enforce Civil Rights Under §5 of the 14th Amendment. A) Confinment of Congress’s Civil Rights Enforcement Power to “Proportional” and “Congruent” Remedies. 1. Congress doesn’t get to decide the scope of the 14th, they just enforce what is determined by the Court. Ex: City of Boerne v. Flores. i. For many years Court used Sherber balancing test that if Congress or a state enacted a law that placed a substantial burden on the free exercise of religion, then that government could only enforce that law if it had a compelling interest in doing so (balancing test). ii. In Smith members of a Native American church were denied unemployment because of peyote use. Court rejects the Sherber test and says that a neutral law (that doesn’t deliberately target a particular group/religion) of general application can be placed even if it causes problems with religious practices. iii. In response Congress adopts RFRA to restore the substantial burden compelling interest test of Sherbert. Court said Congress couldn’t do this under §5, because they don’t get to determne the scope of rights, and RFRA runs afound of that because seems like Congress is trying to broaden rights under 14th. 2. Congress need not wait for a judicial determination of unconstitutionality before prohibiting the enforcement of a state law: Katzenbach v. Morgan. II. A) i. English literacy requirement, , a registered voter in NYC, challenged part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 which rpovdes that any person who has successfully completed sixth grade education in an accredited school in Puerto Rico cannot be denied the right to vote because of lack of English proficiency. claims this prevents the prohibition of NY election laws. ii. Court holds that Congress may prohibit enforcement of a state English literacy voting requirement by legislating under §5 of the 14th Amendment, regardless of whether judiciary would find it unconstitutional. iii. Test is whether the end is legitimate and the means are not prohibited and are consistent with the letter and spirit of the Constituition. The VRA satisfied both of these requirements. 14th amendment constraints on enforcement of the 11th amendment. Citizen of one state cannot sue another state: 11th amendment 1. Enacted in response to Chisholm v. Georgia. Citizen of South Carolina sued GA when goods were received but payment wasn’t. i. 11th says that the judicial power of the US does not extend to any suit in law or equity prosecuted against any citizen of US against another state. State has to waive its sovereign immunity. 2. Over the years the courts have created exceptions. i. Ex parte Young, can sue for prospective/injunctive relief (can’t get damages) and are suing an official of the state(not the state itself). ii. Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, recognizes that Congress has the power to pass l egislation that enforces the rights protected under the 14th amendment, not withstanding state soverign immunity, when legislation is enacted under §5 of the 14th amendment. iii. Seminole Tribe v. FL. Can’t enact legisation based on commerce clause that aggregates soverign immunity; that is under Article I can’t override state soverign immunity, only under 14th. 14th adopted after 11th and one of its purposes was to change the relationship between the federal and state governments. Could still sue for injunctive relief, but took away idea of monetary relief. Doesn’t bar claims by the federal government (although might have a lot of potential claims). iv. Alden v. Maine extends the immunity from Seminole to lawsuits against states in state courts. Congress in exercising its Article I powers may not abrogate state soverign immunity by authorizing private actions for money damages against non-consenting states in their own courts. Not derived from text of 11th, but based on the history and structure of the constitution. 3. Court restrict Congressional action against states (re 11th) under EPC of the 14th: EPC only requires a state to act rationally, even if it discriminates. i. For Congress to abrogate 11th amendment immunity of a state it would have to be done under the 14th amendment which requires due process of law when depriving someone of their property. Ex: Florida Prepaid Post Secondary Expense Board v. College Savings Bank, claim that Florida violated a patent, satute plainly and clearly authorized abrogation of 11th immunity. State notes the potential for a patent to do this, but this statute was not authorized under §5 of the 14th because it fails the congruence and proportionality tests of Boerne. The legislation here wasn’t responding to the type of widespread and persisting deprivation of constitutional rights of the sort Congress has faced in enacting §5 legislation. ii. Kimel v. Florida Board of Regents. Court held that Congress had exceed its 14th amendment remedial authority by allowing state employees to sue the states for damages for violations of the ADEA. Court states that the 14th was the sole source of Congressioanl authority to abrogate soverign immunity. Since ADEA failed congruence and proportionality tests, the attempt to abrogate state soverign immunity was unconstitutional. Congress never identified any pattern of age discrimnation by the states. PART 6: A) FEDERALISM-BASED RESTRAINTS ON OTHER NATIONAL POWERS IN THE 1787 CONSTITUTION. The Taxing Power as a Regulatory Tool 1. Congress cannot pass a law under the pretext of executing its powers, but which is for the accomplishment of objectives not within their power. Ex: Child Labor Tax Case (Bailey v. Drexel Furniture). i. Statute seems to be a response to Court’s ruling in Dagenhart, what Court said Congress couldn’t do through commerce power they are now trying to do through the tax power. ii. Court says this statute isn’t a valid exercise of tax power: its more of a penalty for employers who use children who were underage or worked too many hours. If allow this, then Congress will be able to infringe on other areas. 2. A tax does not cease to be valid just because it has a regulatory effect, nor is it invalid just because the revenue is negligible. Ex: United States v. Kahriger. B) i. 10% tax on bookies and they have to register with the local government. Congress passed this act to surpress gambling. ii. Court said that unless there are penalty provisions that are extraneous to any tax need, courts are without authority to limit the exercise of the tax power. The Spending Power As A Regulatory Device 1. Limitations on Congress ability to condition funding: South Dakota v. Dole: Transportation Department withheld 5% of highway funds if a state didn’t raise its drinking age to 21. State sought a declaratory judgment that this policy violated the 21st amendment and the limits on Congressional spending power. Court outlined 4 limitations on condition funds: i. Exercise of the spending power must be in pursuit of the general welfare: Article I, §8 requirement. This act was judged to be in the general welfare since better highways create safer travel. ii. Must be unambiguous: states need to know what’s going on. Okay here. iii. Related to a federal interest in the program at issue (germaness): Conditions might be illegitimate if they are unrelated to the federal interest in the national program. Ex: in Printz, couldn’t link federal education funds to required background checks. Here, there is no clear relationship. The majority argues there is a sufficient nexus, as the program is designed for safe interstate travel (furthered by not having drunk kids on the road), while O’Connor in dissent says that Congress could attach funds to building a particular type of highway, but this goes beyond what they can do. iv. No independent constitutional bar: can’t ask a state to do something that is otherwise unconstitutional. Here, South Dakota says that the 21st amendment leaves regulating alcohol up to the states. The Court says that Congress can achieve things under the spending power that it could not achieve directly. 2. “Pressure turns to compulsion”: results might be different if, as in South Dakota, Congress threatened to withhold all related funds (here, all highway funds). C) War Powers The War Powers includes the power to remedy problems which have arisen due to the war and does not necessarily end with the cessation of hostilities. Ex: Woods v. Cloyd W. Miller Co. D) i. War time regulation of housing, rent control measure. There is a housing deficit because nothing was built during the war. No question about whether Congress could control rents in the middle of a war, but if they could do it after the cessation of hostilities but still in a technical state of war. ii. Court decides that use of war powers here is valid. Congress can regulate to deal with the effects of war, even though technically hostilities have ceased. iii. Jackson’s concurring opinion: war power is the most dangerous to a free government. Usually invoked in haste, executed in patriotic fervor, and interpreted by judges under the same passions. Would limit the war power in duration (although not in this case). Cannot accept the argument that war powers last as long as the effects and consequences of the war. Treaty Powers 1. Congress can constitutionally enact a statute under Article I, §8 to enforce a treaty created under Article II, §2, even if the statute by itself is unconstitutional. Ex: Missouri v. Holland. i. Treaty between US and Great Britain (Canada) dealing with migratory birds, While some treaties are self-executing, this one required a statute to implement it. That statute was challenged by the state of Missouri. At that time (given commerce clause doctrine), Congress couldn’t have adopted this law. Missouri said the law involved a type of regulation that is a reserved power under the 10th amendment, therefore Congress could not adopt the statute, even to implement the treaty. ii. Court said 10th amendment was irrelevant here because the power to make treaties is expressely delegated to the Federal government. So Congress can adopt a law under the necessary and proper clause to effectuate a treaty that was validly made. 2. Treaty power doesn’t give Congress authority to do things inconsistent with constitution. i. Missouri: Does suggest there might be a limitation that a treaty cannot be valid that requires a direct contradiction of a constitutional provision. ii. Reid v. Covert: treaties involving civilian jurisdiction over civilian dependents of American servicemen. PART 7: FEDERAL LIMITS ON STATE POWER TO REGULATE THE NATIONAL ECONOMY I. State Regulation and the Dormant Commerce Clause A) Generally 1. Limitation on the ability of states to regulate. Concerned about activities that discriminate against interstate commerce or place limitations on it. Comes from Article I, §8, Clause 3. i. Court enforces the dormant commerce clause as opposed to Congress. ii. Congress can give states the authority to do things that would otherwise violate this clause. iii. Some like the clause, say it helps protect those who otherwise wouldn’t be protected. Some justices aren’t fans of it; say that states are designed to protect their own citizens, that if there was discrimination Congress could invoke its commerce power (then they would be looking out for it, not the courts). B) Discriminatory categories 1. A law that’s facially discriminatory will almost always be struck down. i. Ex: Philadelphia v. NJ. NJ legislation creates advantages for NJ residents who want to dispose of solid waste, lowers prices for them (to disadvantage of out of state producers). Court said it didn’t need to decide if the ultimate purpose was competition or protecting the environment (as legislators claimed) because they are discriminating against interstate commerce. Court didn’t buy quaranteen argument since the materials had already moved through the state. If NJ legitimately concerned about landfills filling up they could have taken nondiscriminatory measures to reduce the flow of waste into all landfills (ex tax on usage, restrict certain types of waste regardless of source). ii. Facially discriminatory fees, Ex: Chemical Waste Management. If bring in hazardous waste from out of state, Alabama says tax it. Court says that’s an invalid discrimination against out of state commerce, apply strict scrutiny. iii. Facially discriminatory disposal fees: Ex: Oregon Waste Systems v. Dept. of Environmental Quality. Court found it discriminatory because charging higher fees for out of state waste. iv. Subsidies instead of regulation: Ex: West Lynn Creamery v. Healy. Tax everyone but then rebate the tax to the state’s dairy farmers. Proponents say the tax applies equally to everyone, giving the money back is part of something different (Court has said subsidies are legal). But the Court says that when couple a tax with a rebate of a tax it’s a discriminatory tax and a pure subsidy. v. Facial Discrimination by localities: Ex: Dean Milk v. Madison. Madison, WI authorities say if want to sell milk in Madison must be processed with 5 miles (if it were a state ordinance would be reject like a home processing requirement). Madison justifies it in terms of wanting to protect their own standards. Possible rationale for treating this type of discrimination differently is that it also hurts other in-state producers. If wanted to, Madison could send inspectors to other places and charge for the reasonable cost of that inspection. Ex: Fort Gratiot Sanitary Landfill v. MI Dept. of Nat. Resources, MI law prohibited landfill operators from accepting solid waste from outside the county, Court says its like Philadeplhia. Ex: C&A Carbone Inc. v. Clarkstown; city set up solid waste transfer facility. Built by a private company under agreement to sell to the city after a few years of operation, but the city had to agree to a certain amount of waste going there, so city required local waste to go there even though the facility charged more. Court invalidates it like a local processing case. vi. Applies to nonprofits as well: Ex: Camps Newfoundland/Owatonna v. Town of Harrison. Charitable institution in Maine, exempt from certain state taxes unless operates for purposes not to primarily benefit residents of Maine. Court says not okay, dormant commerce clause also applies to nonprofits (would increase the cost of going to camp for out of staters). vii. Market participation exception (can avoid strict scrutiny): states can discriminate when participating in the market. Ex: state is buying pencils In Camps Newfoundland, Court doesn’t let state use market exception here on the argument that its just going out and purchasing services it would otherwise provide because then it could argue that its always buying something. If a state imposes burdens on commerce within a market in which it is a participant, but which have a substantial regulatory effect outside of that particular market, they are per se invalid. Ex: South-Central Timber Developments v. Wunnicke. Proposed to sell timber but only if the purchaser would partially process the timber in Alaska before it was shipped out of state. iv. Court will approve of a statute that discriminates on its surface if it protects a legitimate local purpose that otherwise couldn’t be served well. Ex: Maine v. Taylor. State concerned with criters on bait fish, and if brought in from elsewhere, will be changing the ecology of the state’s rivers and streams. Court decides there’s no nondiscriminatory means of dealing with this. 2. If its not facially discriminatory, but is discriminatory in purpose or intent will also usually be struck down. i. State barriers to out-of-state sellers: Ex: Baldwin v. Seelig. NY law that if want to sell milk in NY have to buy it at a minimum price to protect the market. NY milk dealer wants to buy milk in VT (lower than NY). Argument that there’s no discrimination since everyone will still get the same price is held to be protectionist by the Court. Court also doesn’t buy protection of health argument by keep milk producers in business, saying if allowed economic welfare to be considered related to health could always come up with protections for local producers. ii. State barriers to out of state buyers: Ex: Milk Control Board v. Eisenberg Farm Products. PA minimum price regulation. Statute here was applied to a NY milk dealer who shipped out of state, but it would also apply to a PA milk dealer. The Court upheld the legislation; it was designed to deal with a local situation, it wasn’t directed at interstate commerce. Court suggests that if try to shield interstate commerce by exempting out of state sales would create problems. However, restrictions imposed for the avowed purpose and with the practical effect of curtailing the volume of interstate commerce to aid local economic interests will not be sustained. Ex: HP Hood & Sons v. Du Mond. NY license is required to establish a depot where milk is shipped out from. wants another facility in NYS, Commissioner thought market would be flooded (wants to prevent milk from going out of state). The Court said this statute violates the dormant commerce clause. iii. Court will allow tax to neutralize advantage by out-of-state producers: Ex: Henneford v. Silas Mason. Court upholds use tax on out-of-state users. If bring something into WA bought in another state have to pay a 2% use tax, so just taking away artificial advantage created by the tax. iv. State statutes with valid good faith purpose that achieves its purpose but burdens interstate commerce will probably, under strict scrutiny, be struck down. Ex: Hunt v. Washington State Apple Advertising Comm’n. NC statute that had to be USDA grade or not grade for consumer protection (so they don’t get confused). However, Washington State also had its own grading system on crates of apples, would otherwise have to repackage and would degrade their competitive advantage. Court overturned this statute using a strict scrutiny test: there were other ways to achieve these objectives. 3. If law is not facially discriminatory in purpose or effect could still be invalid. Don’t use strict scrutiny, use balancing test—burdens on interstate commerce and extent to which it advances legitimate state interests. i. Apply strict scrutiny when a statute is facially discriminatory against interstate commerce. When that happens the Court will say its “virtually per say” invalid. May be held valid if the purpose cannot be served by reasonable nondiscriminatory means. Ex: Pike v. Bruce Church, home processing requirement struck down as facially discriminatory. ii. Non facially discrimiantory statutes looked at using a balancing test. Ex: Pike v. Bruce Church. Court will strike down legislation where the burden on interstate commerce is excessive compared to the putative local benefit. Ex: City Service Gas v. Peerless Oil & Gas. Statute trying to prevent dissipation of its natural resources (being pumped out too quickly). Didn’t matter where the gas was going to be used. Court finds this to be a legitimate protection of state interests; it’s different from a state embargo because don’t distinguish based on where the gas will be used. iii. Use strict scrutiny for discriminatory statutes: Ex: Hughes v. Oklahoma. Couldn’t ship minnows from state waters out of state (unlike City Service where didn’t distinguish where the resource would be used). Court decides it’s unconstitutional under strict scrutiny. iv. Court gives general rule that state can’t try to horde its resources (can’t give its residents preferred right of access from out of state). Ex: New England Power v. New Hampshire. v. State burdens on transportation. A state safety regulation will be unconstitutional if its asserted safety purpose is outweighed by its degree of interstate commerce. Ex: Kassel v. Consolidated Freightways Corp. Regulation that a trailer has to be 60 feet long or less. Consoldiated doesn’t like because that means they have to switch rigs at border, or circumvent the state. Court foes a balancing test, looking at the burden on interstate commerce against the benefit. Says considering Iowa has several major transportation routes there is a substantial burden on interstate commerce and there isn’t much benefit to safety (might be different if it were a Hawaii regulation). Brennan says if Iowa was going for safety then shouldn’t question that, but all they’re trying to do here is make the trucks go elsewhere. Dissent makes argument that legislatures make better decisions about safety than do courts. In Bendix, Scalia suggests that when trying to balance interstate v. state interests, you are trying to balance things that can’t be compared (like trying to decide if a line is as long as a rock is heavy). vi. Interstate commerce protects markets not firms. Ex: Exxon Corp. v. Governor of MD. Law prohibits a gas producer or refiner from operating retail service stations. There were out of state companies that could still operate in MD. Nothing in the law turns upon where a company does business or is incorporated. Doesn’t violate Pike balancing, Court suggests that its not going to place a burden on interstate commerce. Ex: Minnesota v. Clover Leaf Cremery. Court upheld a state law that banned milk products sold in non-recycable plastic. Not facially discriminatory but there was a disparate impact. Most of the acceptable containers were of pulpwood which is produced in MN. However, the law regulated evenhandedly, without regard to whether the containers were in or out of state. There was also a legitimate state interest; solid waste disposal and energy concervation. vii. Cases dealing with business interests, ability to enter into a state. Ex: Edgar v. MITE Corp. IL law that attempts to regulate tender offers made to garget companies with certain contacts in IL. Regulation requirements would tend to make take-overs more difficult. Court holds the statute unconstitutional. It imposes a substantial burden on interstate commerce which outweighs the local benefits. Ex: CTS Corp v. Dynamics Corp. Disinterested stock holders get to vote on whether to acquire majority status. Applies to Indiana corps, which made it different than Edgar where any business that had contact with the state had to comply. II. The Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV A) 2 Privileges and Immunities Clauses 1. Article IV, §2: “the citizens of each state shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states.” i. privileges and immunities of state citzenship. 2. 14th amendment, §1: “no state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” i. B) privilges and immunities of US citizenship. Scope of privileges and immunitiesu 1. Fundamental rights or activites: not every right of citizenship. i. ex: elk hunting license is not protected by p&I. ii. ex: practicing law is protected; its important to the national economy, and its important that attorneys be able to raise claims under federal law. 2. Corporations are not entitled to protection: The clause protects individuals. Corporations are not citizens of the state. 3. Congress may not be able to override privileges and immunities (as they can for dormant commerce). Dormant commerce clause is an implied restraint, p&I is a grant of right to individuals. C) 2 step analysis to determine if there is discrimination under privileges and immunities: 1. Is there a privilege or immunity? i. Ex: United Building v. Mayor and Council of Camden. Municipal law requiring at least 40% of the employees of contractors and subcontractors working on city construction projects to be Camden residents. Court rejects argument that p&i shouldn’t apply to city (exercising power from state so same). Also rejects argument that in-state residents are being discriminated against as well. However, those in-state residents could challenge this discrimination in the legislature, whereas the out of state residents could not. 2. Is there a rational reason for discriminating against nonresidents? i. Ex: United Building v. Mayor and Council of Camden. The privileges and immunities clause does not preclude discrimination against out-of-state residents if there is a substantial reason, for the difference in treatment. Although alleges several such reasons—including increasing unemployment in the city, declining population, and a depleted tax base—not trial has been held and no findings of fact have been made. Case must be remanded.