JAll, THEN AND NOW

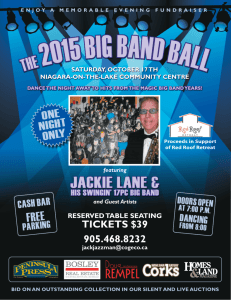

advertisement