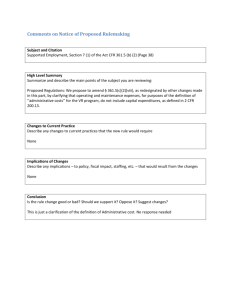

agenda - American Bar Association

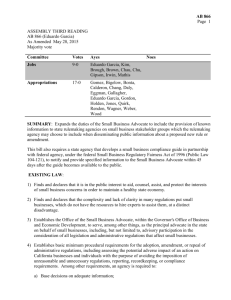

advertisement